Misconceptions about Irregular Warfare have Wasted U.S. Influence in the Sahel

By Capt. Juan Quiroz, Civil Affairs Officer

Photo provided by Adobe Stock

The number of violent episodes in the Sahel region of Africa, centered around Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, has

quadrupled from 700 incidents in 2019 to over 2,800 incidents in 2022. 01 Despite providing years of training and

assistance to these countries’ militaries, U.S. Army special operations forces (ARSOF) efforts to contain

the territorial expansion of violent extremist organizations have proven ineffective. This has been due largely

to a one-dimensional approach to irregular warfare, whereby well-meaning outside actors, including ARSOF,

attempted to root out violent extremist organizations but inadvertently reinforced central governments’

misperception that their first priority was public safety, clean water, food sources, and so on. The local

governments emphasized the military’s focus on security over stability tasks undermined the other

essential forms of support to governance. The people of the Sahel require less security and more governance

– that is, the provision of clean water and a stable food source. The result has been declining U.S.

influence in the region since 2020 as these states’ armed forces have overthrown their democratically

elected governments and turned to Russia for diplomatic support and military aid. To utilize Irregular Warfare

more effectively in a while-of-government effort, ARSOF practitioners must reexamine the purpose of Irregular

Warfare and coordinate a more impactful range of operations and activities. This includes the use of interagency

partners as the lead agency. The U.S. federal agencies, such as the Department of State and U.S. Agency for

International Development, should take the lead on this total effort. When using conventional or special

operations forces, the Irregular Warfare-related activities and operations should focus more on provision of

essential services and less on physical security against terrorist or criminal threats.

Reexamining Irregular Warfare

The ARSOF’s narrow conceptualization of how to conduct Irregular Warfare can be attributed to the lag in

updating doctrine to reflect the dynamics ARSOF Soldiers encounter in the current operational environment. Field

Manual 3-05, Army Special Operations, still defines Irregular Warfare as “a violent struggle among state

and nonstate actors for legitimacy and influence over relevant populations.” 02 The manual elaborates that influence can be

exercised through “political, psychological, and economic methods,” but its predominant focus is on

kinetic activities such as terrorism, insurgency, criminal activity, and raids. 03 Joint Publication 3-05, Joint Doctrine for

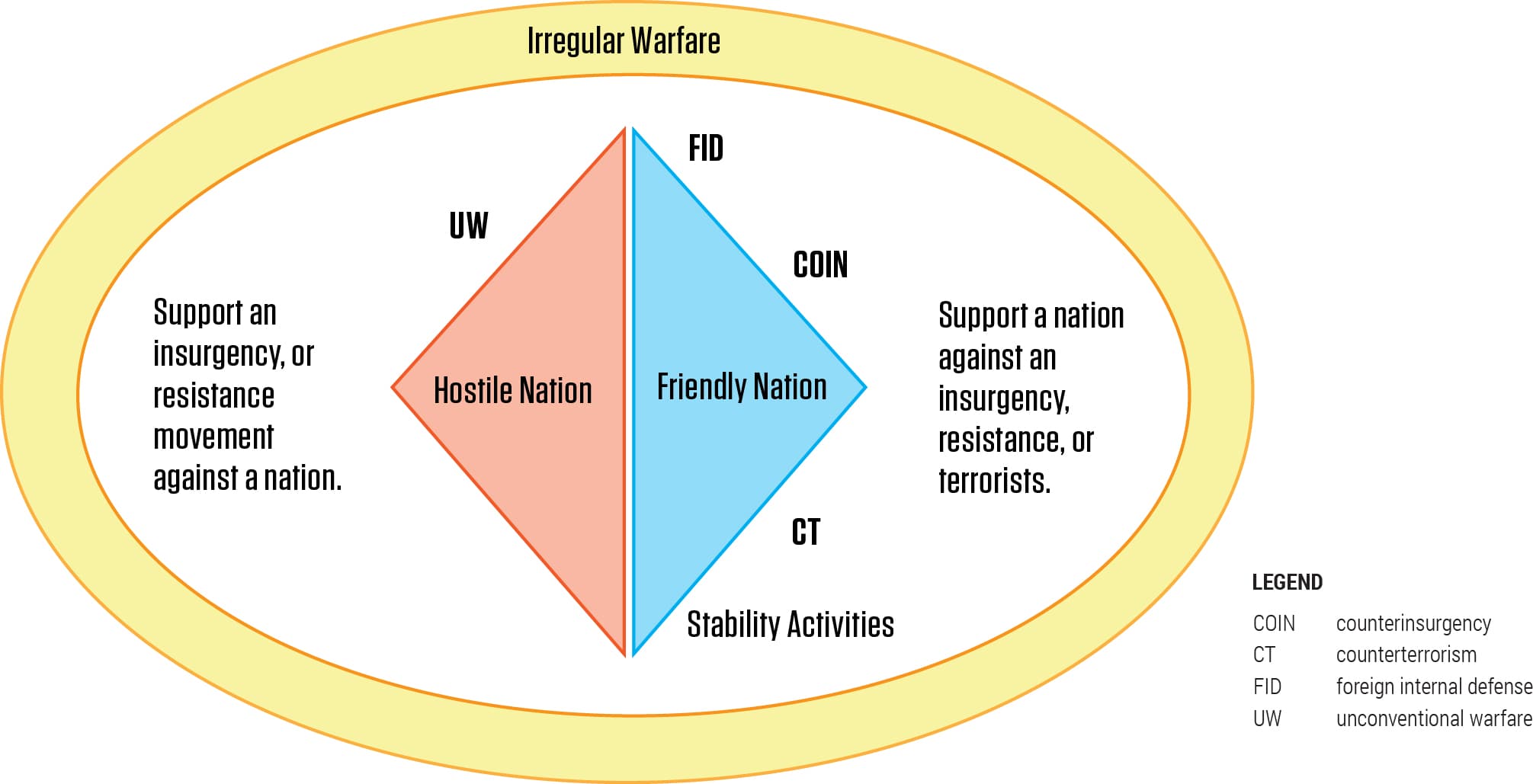

Special Operations, does not improve our understanding, and presents a reductive view of Irregular Warfare that

bins different types of kinetic activities according to whether a nation is classified as friendly or hostile.

04

These out-of-date publications and associated figures (above) fail to convey the real reason state and non-state

actors participate in conflict—failure to achieve economic, political, or social objectives through

nonviolent means. Additionally, a simple fix to the above model might make “stability activities”

the main effort by its position on the slide; this would reflect a preeminent role of nonkinetic versus kinetic

activities. Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian general and military theorist from the 1800s, described these

objectives as “the original motive for war,” and any changes to belligerents’ objectives or

concessions made to opponents can affect the need or desirability to continue waging war. 05 In contrast to current special operations

doctrine, JP 1, Volume 1, Joint Warfighting, offers a more expansive description of Irregular Warfare as a form

of warfare, where states and non-state actors campaign to “assure or coerce states or other groups through

indirect, non-attributable, or asymmetric activities.” 06 Conventional Army doctrine has also been updated to reflect the

essentially political character of IW. FM 3-0, Operations, and FM 1-02.1, Operational Terms, define Irregular

Warfare as “the overt, clandestine, and covert employment of military and non-military capabilities across

multiple domains by state and non-state actors through methods other than military domination of an adversary,

either as the primary approach or in concert with conventional warfare.” 07 In conjunction with the theory presented by

Clausewitz, these new definitions grant leeway to ARSOF Soldiers to think more creatively about Irregular

Warfare in terms of simultaneously assuring partners and coercing belligerents through military and nonmilitary

means to accept and adhere to political settlements advantageous to U.S. interests. This new Irregular Warfare

concept is especially relevant in the Sahel, where the complex web of partner and adversary objectives

demonstrate that the old Irregular Warfare tug-of-war for populations’ loyalties is impractical and

counterproductive.

Relationship between special operations activities support for or against a nation during

irregular warfare

Conflict Dynamics in the Sahel

Desertification in the Sahel region has intensified historic resource competition between nomadic and sedentary

tribes. Because this competition occurred far from their capitals, central governments engaged in “benign

neglect,” tacitly condoning the marginalization of nomadic pastoralists by sedentary communities who seek

exclusive control of fertile land. 08 This inequitable arrangement caused disputes when the two sides came

into contact, but government apparatuses, while limited, were usually able to mediate resolutions. This

arrangement has now become so inequitable that tribal clashes are becoming larger and more violent. Central

governments have done little to address the resource shortfalls due to their limited governance capability and

reach into this region. To give this historical context, France, the region’s former colonial power, had

89 civil servants per 1,000 inhabitants. Today, by comparison, it is estimated that Burkina Faso has only eight

civil servants per 1,000 inhabitants, Mali six, and Niger three. 09

Because these governments have little to no presence outside their capitals, military action is relied upon to

project authority and act as the face of government to peripheral communities. Rather than acting as impartial

security guarantors, these government forces tend to support certain tribal militias who are focused on settling

tribal rivalries instead of providing any form of governance in the region. 10 This measure has backfired significantly,

however, as marginalized communities prefer to align with violent extremist organizations considered to be less

dangerous than government forces. 11 This local alliance and introduction of violent extremist organizations

into the conflict creates a vicious cycle in which participants overinvest in temporary security at the expense

of enduring governance. With most assistance coming in the form of military training and support, which tends to

gravitate toward a physical threat, these governments fail to develop a governance capacity that looks to

developing essential services in tandem with military capacity. This environment, absent of the unique skillset

resident in U.S. Army Civil Affairs, ultimately results in the military coup scenarios witnessed in Mali,

Burkina Faso, Chad, and Niger. 12

In the aftermath of these coups, Russia positioned itself as the security partner by default. Playing on this

contradiction, Russia leverages disinformation to turn public opinion against Western assistance and deploys

Wagner mercenaries who inflame government forces’ worst instincts to commit even more atrocities, which

further increases support for violent extremist organizations. 13 As Sahel governments become more complicit in human rights abuses

against their own people, the rift between them and former international and Western partners widens. With these

governments becoming increasingly dependent upon Russia to maintain their hold on power, any plausible avenue to

exert U.S. influence in the region becomes increasingly problematic.

How to Wage Irregular Warfare in the Sahel

To date, although well intended, ARSOF and U.S. interagency partners efforts through and with regional and

central governments to bolster their security and governance capacity had little effect. Instead, an increase in

violent extremist organizations activity in the periphery and Russian influence in the capitals persists. This

unintended effect is due to wrongly equating strong central governments with stability and security. Some

communities in the periphery may be wary of, or even outright hostile to, the idea of being drawn closer to

central governments that ignore them in the best of times and commit atrocities against them in the worst of

times. They may feel similarly about the violent extremist organizations with whom they occasionally ally. The

ARSOF, which prides itself on its indigenous or irregular approach to challenges such as this, can add value by

engaging directly with communities in peripheral regions. They can engage adjacent tribal groups to discover

their motivation for waging war against each other, violent extremist organizations, or government forces, and

establish the United States as an honest broker between belligerents. Perhaps their idea of stability is

contingent on economic security or mending intercommunal relations rather than a greater government presence and

the use of military force.

Once ARSOF elements have established trust with belligerents and understand their motivations, the U.S.

interagency can also adopt a more indigenous and irregular approach to correct the imbalances that sparked

conflict. Development and trade agencies can assure communities that violent resource competition is no longer

necessary by working directly with their leaders to furnish humanitarian aid, foster commercial activity, and

develop an indigenous capacity to independently sustain economic security. ARSOF could leverage ties with

government and indigenous forces to deescalate tensions and, if needed, to implement stability mechanisms and

target irreconcilable elements. Diplomatic personnel would have to broker power-sharing arrangements between

local communities and central governments and then hold central governments accountable if they violate the

agreements.

Conclusion

By reframing Irregular Warfare as the shaping of partner and belligerent behavior through simultaneous assurance

and coercion, ARSOF can employ a wider range of activities like foreign internal defense, stability, and Civil

Affairs operations to be more effective in achieving a political settlement favorable to U.S. interests. This is

especially crucial in support of integrated deterrence where ARSOF offers a military option of relative

advantage. In these conflicts, ARSOF would be best employed in support of interagency and host-nation

counterparts who possess the appropriate mandate to address the issues driving conflict at the local level.

Their diplomatic, economic, and governance effects could change belligerents’ strategic calculus

concerning whether instability and conflict should persist.

If ARSOF is to be successful in the application of Irregular Warfare across the competition continuum, especially

in the Sahel, ARSOF must update its special operations and associated Irregular Warfare doctrine to reflect the

oversized value of the nonkinetic aspects of a whole-of-government integration of the military across the

competition continuum. Violent extremist organizations and the threat that they pose are not the result of

failed physical security protocols. Instead, violent extremist organizations thrive in an area where there is a

real or perceived lack of water, food, and general economic security. If ARSOF were to focus more on its Civil

Affairs and military information support operations and use them in support of a larger interagency effort,

ARSOF would then be more successful and provide greater value to the joint force and the U.S. country team. In

the ubiquitous DIME model DoD uses to explain the four elements (Diplomacy, Information, Military, and

Economics) of U.S. national power, ARSOF must shrink the large M down to a small m. If ARSOF are to be

successful in the Sahel and other areas like it, then ARSOF must adjust the DIME spelling to DImE. 14

Notes

03. Department of the Army, FM 3-05, pg. 1-2.

13. Mvemba Phezo Dizolele and Catrine Doxsee, The

Wagner Group: The Kremlin’s Indispensable Hand in Africa, CSIS Into Africa, podcast audio, July

27, 2023, https://www.csis.org/podcasts/africa/wagner-group-kremlins-indispensable-hand-africa;

Zane Irwin and Sam Mednick, “Mali’s army and suspected Russia-linked mercenaries committed

‘new atrocities,’ rights group says,” AP News, July 24, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/mali-human-rights-abuses-wagner-military-fulani-19a045521448453dd9ecb5b464941955.

14. Interview with LTC Timothy J. Murphy, Director,

U.S. Army Irregular Warfare Proponent, 21 March 2024.