Signal Corps Support Of Amphibious Operations

January - March 1944

Steven J. Rauch, Signal Corps Branch Historian

Article published on: April 1, 2024 in the Army Communicator Spring 2024 Edition

Read Time: < 14 mins

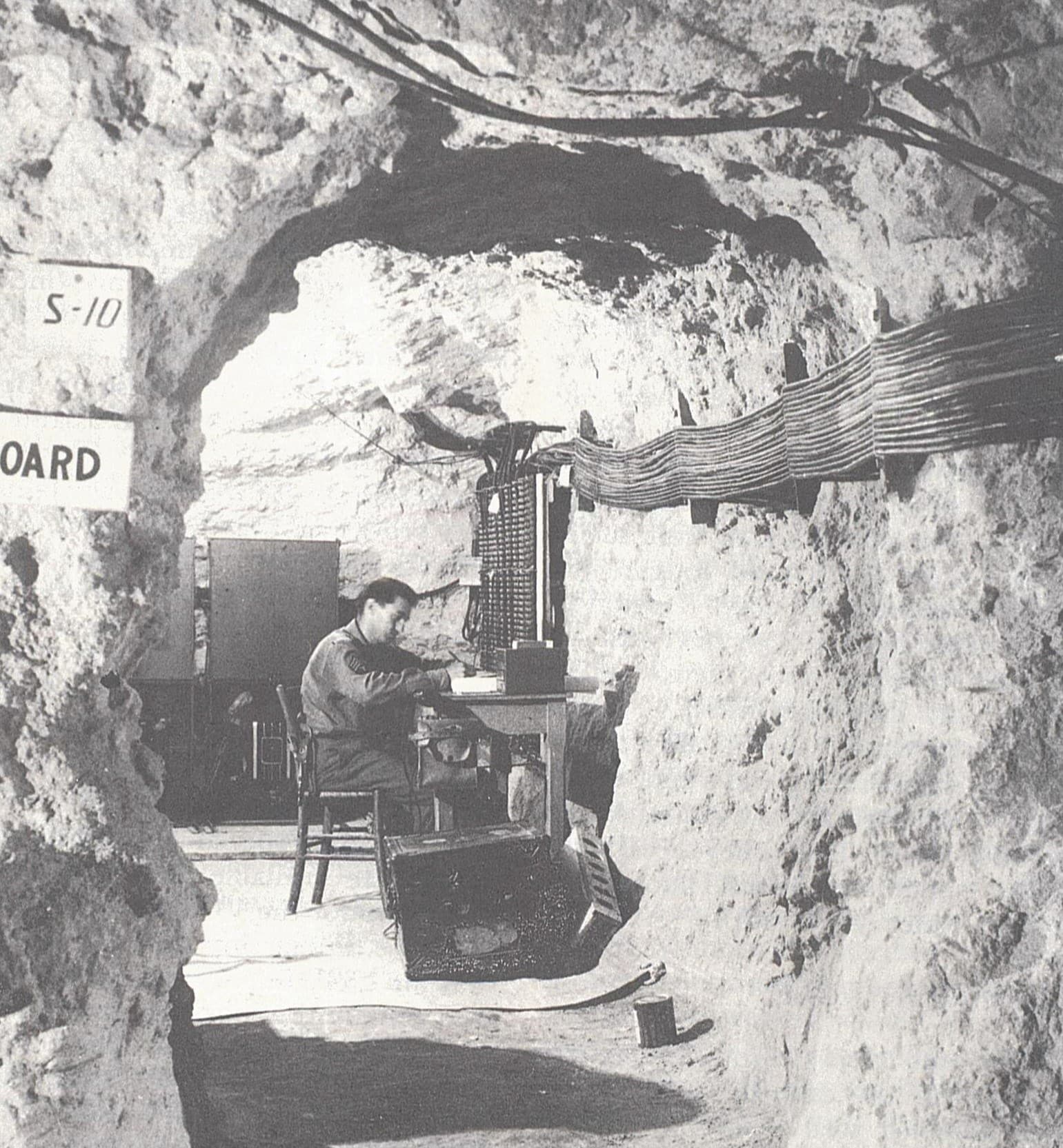

A wine cellar tunnel system used to protect communication lines during Anzio, 1944. Radio was the sole means of communicating during initial stages of the operation.

In early 1944, within a span of a few weeks and separated by thousands of miles, three U.S. Army divisions moved by sea to forcibility seize key terrain to support operational and strategic objectives using amphibious landing techniques. Signal Soldiers who were assigned to division signal companies and supporting corps signal battalions all shared one thing in common: the challenge of providing communications in the air, sea, and land environments during large scale combat operations against peer adversaries. But wait. You thought that was the job of U.S. Marines? Not so.

During World War II, the Army conducted more amphibious landings than the Marine Corps in all theaters of operations. In the Pacific, the Army employed 22 divisions whereas the Marines had only six; a 3-to-1 ratio of combat power. It is still an Army mission today. According to Field Manual 3-0, Operations, when operating in a maritime environment, “Army forces are likely to conduct two complex forms of forcible entry operations: airborne or air assault and amphibious landing. Forcible entry operations seize and hold lodgments against armed opposition to set conditions for follow-on operations.”

This article offers just a few highlights of the challenges signal Soldiers faced during the landing at Anzio, Italy, by the 3rd Infantry Division (ID) in late January 1944; the assault on Kwajalein Island by 7th Infantry Division in early February 1944; and the extremely violent combat experienced by 1st Cavalry Division (CD) on Los Negros Island in late February 1944.

3rd Infantry Division at Anzio, January 1944

Opposed landings in a maritime environment are one of the most difficult and dangerous military operations, so achieving the element of surprise should be pursued by all available means. FM 3-0 (p. 7-14)

D-Day was sunny and warm for the Soldiers of 3rd ID who landed at Anzio Beach on Jan. 22. Even better was the lack of enemy resistance due to achieving complete surprise with an amphibious assault behind Axis lines. The U.S. VI Corps was given the mission to land two divisions at Anzio Beach, then move inland to cut off enemy resistance to the south, link up with Fifth Army and open the way to Rome to the north.

The communications plan for Anzio drew upon lessons learned from the Salerno landing in 1943. During the seaborne phase of Anzio, VI Corps used a specially designed headquarters ship Biscayne. The 3rd ID used a converted Landing Ship Tank (LST) for its headquarters with vehicular radio sets SCR-399 and 193, loaded on the top deck of the ship for radio communication to Fifth Army. At Anzio, VI Corps operated independently because it was establishing a beachhead behind enemy lines, so there was no wire communication with Fifth Army. That meant radio was the sole means of communication during initial stages of the operation. Within 3rd ID, the SCR-300 “walkie-talkie” – the first portable manpack FM radio designed for use by infantry units – was relied upon for all communication networks above company level.

According to Lt. Col. Jesse F. Thomas, the division G6, “It was the most successful instrument yet devised for amphibious communications. Its range and reliability met or exceeded every expectation and established it as the most valuable item of radio equipment in the division.”

Even though the batteries for the radio were rated to last 24 hours, in some cases they lasted up to 40 hours. Two DUKW amphibious vehicle mounted SCR-499 radio sets from the 57th Signal Battalion went ashore about noon on D-Day to provide radio communication for the corps combat patrols (CP) and reconnaissance elements. The only personnel from 57th to land on D-Day were those who could climb aboard the DUKWs. This group consisted of reconnaissance personnel, radio operators, and messengers. The corps CP was established in a group of buildings near the beach and a radio set was put in operation to establish communications with both the headquarters ship and Fifth Army.

By the day after D-Day, the corps CP was up and running with switchboards, message centers, and radio stations installed and working. The signal Soldiers were very experienced in setting up communications for offensive operations, and for about a week everything worked perfectly. Many serviceable commercial and military wire facilities were discovered in the area, which were quickly rehabilitated and put into service. However, any thoughts of an easy landing and quick victory were smashed by strong enemy counterattacks Feb. 3, which threatened to throw the Allies back into the Mediterranean Sea.

During the next several days, the Allies had to shift quickly to defensive operations within a confined and extremely congested area. Intensive enemy artillery fire and air attacks tore up cable and field wire, to include main and alternate circuits. Day by day, the maintenance of circuits was a challenge and dangerous for those signalmen who had to venture onto the battlefield to install or repair lines during intense enemy bombardments.

Soldiers of 1st Signal Troop emplacing wire using a DUKW amphibious vehicle at Los Negros Island. (Photo from Signal Historical Collection)

Defensive operations, however, required more wire than had initially been planned because of a need to install double and triple circuits, multiple lateral lines, and then burying them for protection. Fortunately, the Anzio area was a wine producing region and hundreds of wine cellars and underground tunnels were available to use to route cable and wire to the corps CP. After six weeks of continuous bombing, shelling, and fighting, the battle for Anzio settled into a three-month long stalemate which lasted until spring. For its service during the challenging operation, the 3rd Signal Company was recognized with a Meritorious Service Unit Plaque, which stated, “Throughout preparations for and participation in the Anzio Beachhead campaign and the breakthrough operation culminating in the capture of Rome, Italy, the 3rd Signal Company rendered invaluable service to the Division by installing and maintaining vital communications lines and services. Although subject to constant enemy artillery and occasional small arms fire, and despite obstacles of terrain and weather, the personnel performed their tasks in a superior manner, ensuring continuous efficient communications among all elements of the Division at all times.”

The operations at Anzio proved that sound basic and specialist training was essential for all signal personnel to maintenance effective communications. It also illustrated that flexibility and the ability to improvise was required to meet unexpected situations.

7th Infantry Division at Kwajalein, Marshall Islands, February 1944

In a predominately maritime joint operations area, naval and air components are typically the key components of the joint force commander’s (JFC) operational approach. Army forces develop a nested operational approach that reflects and supports the JFC plan. FM 3-0 (p. 7-9)

In the Central Pacific theater, Adm. Chester Nimitz devised an operational concept known as “island hopping” to seize bases to support a potential invasion of Japan. In November 1943, Nimitz’s forces had seized Tarawa and Makin in the Gilbert Islands. The Gilberts was the first time American ground forces assaulted heavily fortified enemy positions from the sea. The 27th Infantry Division had secured Makin against light resistance, but the 2nd Marine Division suffered some of the heaviest casualty rates during the fight for Tarawa. Nimitz’s next objective was the Marshall Islands, which included 32 separate island groups spread over 400,000 square miles of ocean. The islands were narrow, flat, only two to three miles long, and rose only about 20 feet above sea level. Kwajalein, the world’s largest coral atoll, was in the middle of the Marshalls, approximately 2,100 nautical miles southwest of Pearl Harbor. Kwajalein Island was only two and one-half miles long and 800 yards wide for most of its length, but the Japanese were able to build a 5,000-foot runway capable of handling large numbers of aircraft. The capture of that airfield became a primary objective. Nimitz’s plan was for the 4th Marine Division to seize the dual island of Roi-Namur in the northeast while the 7th ID attacked Kwajalein Island at the southeast end of the atoll. This would be the 7th ID’s second amphibious operation of the war, having seized Attu from the Japanese in the Aleutian Islands in early 1943. The 7th was sent to Hawaii, where it received training in advanced amphibious techniques, marksmanship, and jungle warfare. In addition, a new unit was created to facilitate more effective communication between the services: the 75th Joint Assault Signal Company (JASCO). The 75th JASCO was augmented with navy shore fire control parties and air liaison parties, which brought its strength to almost 600 men. The JASCO’s purpose was to implement common communications procedures to enable all services to effectively communicate during an amphibious assault. These included joint radio frequencies, joint message transmission procedures, joint coordination for close air support, and control of naval gunfire against shore targets.

The plan was for 7th ID to land on the western end of Kwajalein and attack with two regiments abreast. The day prior, the division would seize four smaller islands near Kwajalein as bases for the division artillery to support the landing. The division command group established command and control for the battle onboard the USS Rocky Mount. The Rocky Mount was a specially equipped headquarters ship with the latest radio and radar technology to enable commanders, both afloat and ashore, to direct multiple amphibious operations.

On Feb. 1, 1944, at 9:30 a.m., the two infantry regiments, supported by signalers from 7th Signal Company, landed on Kwajalein. Enemy mortar and automatic weapons fire greeted the troops when they stormed ashore. During this phase, radios were the primary means of communications since they provided freedom of movement and allowed commanders to adjust artillery fire from adjacent islands. By the end of the first day, the division established a CP on Carlson Island. During the battle, the JASCO and 7th Signal Company installed a switchboard on the beach and ran 4,500 yards of submarine cable to connect the command posts on both islands. Throughout the battle, the cable continuously rubbed against the coral reef and would periodically break, so a dedicated repair team from the JASCO was tasked to keep the cable operational.

The next morning, the regiments continued the attack using tank-infantry teams. In previous battles, infantry Soldiers had difficulty communicating with tank commanders. To remedy this, telephones were installed on the outside of the tanks. When a Soldier wanted to communicate with the tank commander, he would walk up to the rear of the tank where the telephone was located and lift the handset, which turned on a light inside the tank, which told the crew the infantry wanted to talk to them. When the tank commander answered, the Soldier could direct him to the needed area.

All resistance ended by the third day as the Soldiers finished their sweep of the island. Among many things the landing validated was the JASCO concept, which helped to mitigate problems in joint communications. As a result, the Army created several more JASCOs to support all theaters of operations.

1st Cavalry Division, Los Negros, Admiralty Islands, February 1944

Retaining critical island terrain through an effective defense, one that includes counter reconnaissance and security operations, is vital for the success of the JFC’s objectives to deny enemy forces a relative advantage. FM 3-0 (p. 7-10)

In contrast to the Central Pacific, Gen. Douglas McArthur commanded the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), which included Australia, the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, the Bismarck Archipelago, and New Guinea. MacArthur controlled army, navy, marine, and air force components from Allied nations, but he drew most of his forces from Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army. MacArthur intended for his next operation to be aimed at the Admiralty Islands. Unlike the Marshall Islands, the Admiralties were volcanic islands with steep mountains, dense jungles, and malaria-breeding swamps.

The specific objective was two large islands, Manus and Los Negros, which were separated by a narrow strait that resembled a horseshoe curve. The interior of this curve, Seeadler Harbor, formed the finest natural anchorage for ships in the southern Pacific. Gaining that harbor for the Navy was critical for future operations. Krueger assigned the capture of the islands to the 1st Cavalry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Innis Swift. The division was organized with two brigades, each having two regiments and two squadrons in each regiment. Although the Admiralties would be its first combat action, 1st Cav. Soldiers had received extensive training to prepare them for their mission to seize Seeadler Harbor.

On Feb. 23, reconnaissance aircraft reported no signs of enemy activity on the islands. On Feb. 27, a small reconnaissance patrol landed on Los Negros and reported the island was occupied by well-camouflaged Japanese troops who had not been detected by the air reconnaissance. Based on this report, MacArthur ordered a strong ground reconnaissance to probe Los Negros. The 2/5 Cavalry Squadron was selected to spearhead the amphibious landing. Brig. Gen. William Chase, 1st Brigade commander, led the task force. Because of the confusing intelligence, MacArthur decided to personally observe the initial assault so he could determine whether the operation should continue or be aborted.

On the morning of Feb. 29, the 2/5 Cav landed on the east side of Los Negros. The Japanese did not anticipate a landing there, and most of their forces were concentrated to defend the beaches of Seeadler Harbor. The landing proceeded on schedule, and by noon the entire 2/5 Cav was ashore and had established a small defensive perimeter around an airfield. MacArthur arrived in the area sometime after 3 p.m., where he inspected the perimeter, presented awards, and expressed satisfaction with the operation’s progress. Before leaving, he told Chase, “Hold what you have taken, no matter against what odds.”

During the first 24 hours, the Army had no communications back to headquarters other than through Navy ships. The Sixth Army signal officer, Col. Harry Reichelderfer, had planned for several large, truck mounted, long-range SCR-399s, along with personnel, to land with task force. But during later planning sessions attended by Reichelderfer’s deputy, Krueger, decided the SCR-399s took up too much shipping space and ordered them left behind. As soon as he learned the SCR-399s were not on the beach with the 2/5 Cav, Reichelderfer made arrangements for them to be loaded onto two LSTs and sent to Los Negros, however they did not reach the area until the next morning.

After MacArthur’s departure, the cavalrymen prepared for a Japanese counterattack. Chase ordered his men to dig in, but they soon discovered digging into coral required picks and shovels to make any progress. Meanwhile, the Japanese commander had issued an order stating, “Tonight, the battalion under Captain Baba will annihilate the enemy who have landed. Be resolute to sacrifice your life for the Emperor, and commit suicide in case capture is imminent.” The attack on the 2/5 Cav defensive perimeter began after dark, and the Japanese attempted to infiltrate small groups of Soldiers through the American lines. Even though the troopers poured withering fire into the enemy line that killed scores of Japanese, the enemy pressed his attacks throughout the night. Although the integrity of the defensive position was maintained, some Japanese were able to crawl between the American positions and penetrate the perimeter.

The Japanese attack ended at dawn on March 1, but it was renewed that afternoon. A 15-man unit commanded by Capt. Masao Baba, which had infiltrated the perimeter the previous night, executed a suicide attack on the 2/5 Cav. command post. Alert staff officers defended the CP, and any enemy survivors committed suicide. The same day, Capt. Joseph Tuck, communications officer of the 1st Brigade Headquarters, was laying wire for the CP when he was caught by fire from an enemy bunker. He saw a wounded signal combat photographer in front of the bunker, and as he dragged him to safety, Tuck received a severe wound. When the enemy threw a grenade to finish him off, Tuck caught the grenade and tossed it back into the bunker, which destroyed the enemy position.

Soldiers of 7th ID using an SCR-300 walkie-talkie at Kwajalein Island in 1944. (Illustration from the Signal Historical Collection)

On March 2, the entire 5th Cavalry Regiment was ashore along with supporting elements. While on reconnaissance, Pvt. Leo W. Zoeller and Master Sgt. David P. Garvin of Charlie Company, 583rd Signal Battalion, encountered grenade and machine gun fire from an enemy bunker. Garvin kept the enemy pinned down with fire while Zoeller obtained some grenades and threw them into the bunker entrance, killing four of the enemy. Garvin then killed the remaining men in the position and captured valuable documents and equipment.

By March 4, the worst of the fighting was over, and having defeated a numerically superior enemy, the men of 5th Cavalry had secured a solid foothold on Los Negros. This was an example where the initial lack of communications equipment, though important, was the result of a commander concerned with transportation limitations. It is ultimately the commander’s call, but the signal officers must ensure he or she understands the risk of not having a capability at the initial stages of conflict.

These examples of Army amphibious operations provide just a glimpse into the variety of challenges encountered during early 1944. Experience gained from these instances of forced entry operations would be passed on as lessons learned for the many subsequent Army amphibious operations in the coming year.

During the remainder of 1944, the Army would demonstrate its expertise in this form of joint warfare, ranging from Normandy and the coast of southern France to the islands of Guam and Saipan, and the return to the Philippines at Leyte.