SPECIAL OPERATIONS and Counter-Occupation

By Brian Petit, Joint Special Operations University and retired Special Forces office

Article published: on April 1st, in the spring 2024 issue of the Special Warfare Journal

Read Time: < 12 mins

Are Army special operations forces (ARSOF) capable of advising Ukrainian units who must operate deep inside Russian occupied territory? Can remote train-and-advise programs far from the line of contact genuinely provide the knowledge, skills, and training to enable partisan networks to strike deep within occupied areas? Tis is an exceptionally difcult undertaking for ARSOF Soldiers and their support elements. If tasked, a mission brief might sound like this:

Your mission is to enable rear-area operations via individuals and networks to organize and operate in Russian-controlled occupied areas of Ukraine. You cannot go to the front line or even into the theater of war. Most of your partners do not speak English. Most do not have military or security force backgrounds. Many have been in sustained combat for two years. The Russian occupying forces they face are a mix of conscripts, paramilitaries, criminals, and deputized collaborators. To access the areas under occupation, one must first penetrate 80 kilometers into heavily defended territory covered by artillery, air support, and pervasive electronic surveillance. What are your questions?

U.S. Army Special Forces Soldiers. U.S.Army photo

If your initial reaction is that your education, training, and experience is inadequate to fulfll this mandate, you are not alone. Te U.S. military has rarely faced such a complex environment, directly or indirectly, in the modern era. Few, if any, ARSOF Soldiers have direct experience with these types of challenges. To date, U.S. policy restricts the ability to gain direct experience and inhibits observational learning; nevertheless, select ARSOF elements are engaged in this counter-occupation mission.

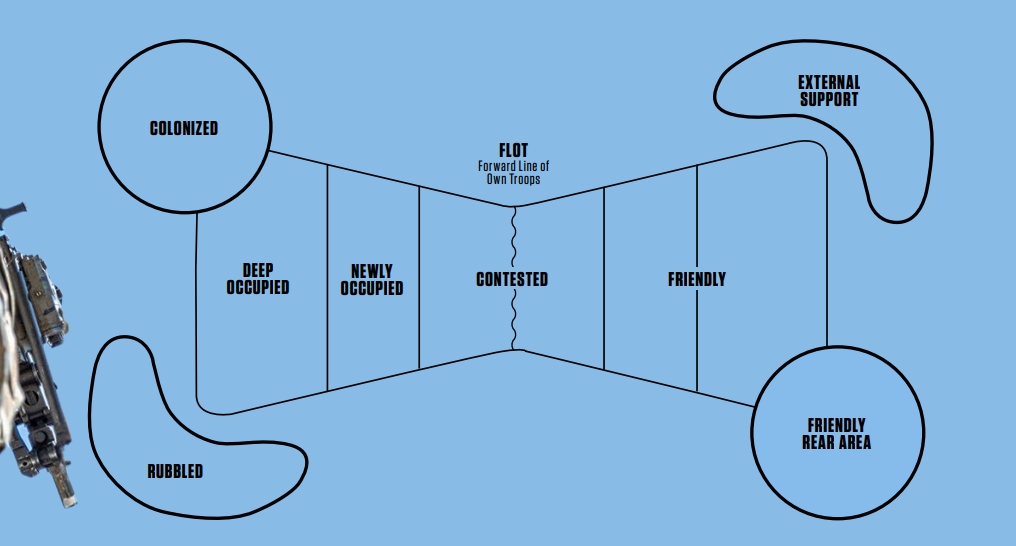

To counter occupation, we must better comprehend what occupation truly entails. Tis article is designed to strengthen that understanding in several key areas. First, a model is introduced to help visualize occupied areas. Second, a review of populace and resource control measures is discussed. Tird, occupation gradients are described using the Russian occupation of Ukraine as an example. Tis model, simplifed for brevity, shows seven gradients of the occupation environment: friendly, forward line of troops, contested, newly occupied, deep occupied, rubbled, and colonized. (Tis article focuses on the newly occupied and deep occupied zones.) Finally, the article examines implications for ARSOF.

To be clear, understanding and operating in such an environment requires a full suite of study and analytical rigor. As an adjunct for the Joint Special Operations University, I provide in-stride education that prepares ARSOF to advise resistance movements. In that work, the Ukraine-Russia War exposed the limits of my own understanding of occupation. This article aims to shrink that knowledge gap and introduce nondoctrinal and training concepts that may inform future consideration in that regard.

AN OCCUPATION TEMPLATE: SPATIAL AND SEVERITY

To clarify occupation zones, I use a visual that approximates U.S. Army doctrinal templates that illustrate depth and force arrayal. Tis template (fgure 1) focuses on two features of an occupied area: spatial and severity. Te goal is to capture the gradients of occupier control as measured by distance and depth (spatial) and by severity (occupation measures). Tis model has two aims. Te frst is to help us see beyond the dualistic enemy and friendly line of demarcation, which insufciently characterizes occupied areas. Te second is to assemble and contextualize the specifcs of a particular type of occupation environment. Tis model cannot replace a properly stafed (and likely classifed) detailed intelligence picture, but it has proven useful in nontraditional settings to share knowledge and to visually animate the peculiarities of an occupied space.

OCCUPATION TEMPLATE: SPATIAL AND SEVERITY

Figure 1: Occupation template, by Brian Petit

POPULACE AND RESOURCES CONTROL

Common to all occupied areas are populace and resource control measures. Te measures are the tactics adopted by a government or occupier to monitor, regulate, and control a population and its material resources. Mapping populace and resource control measures is less an exercise in “red versus blue” force arrayal; it instead seeks to display the interactive and behavioral characteristics of a restricted area.

Tactical populace and resources control measures include outposts, checkpoints, secondary searches, identifcation cards, rations cards, screening methods (such as visual profling, scraping electronics, and canines), and technical enablers. Te proliferation of electronic surveillance is expanding the suite of populace and resource control tools.

Occupation zones produce unique concoctions of populace and resource control measures that dominate patterns of life, drive behavioral norms, restrict movement, track the activities of humans and machines, and catalog the signatures of signals and spectrums.

U.S. Army doctrine acknowledges populace and resource control, but it does so mostly in a scattershot manner across various publications 01– mainly in the context of conducting counterinsurgency and stabilization operations. One excellent resource is “Who Owns the Neighborhood,” a populace and resource control handbook published by the 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne) in 2008.02Although there are some similarities in how the United States and her adversaries might separate insurgents from the population, there are also stark diferences. For example, Russian occupation behaviors employ a multitude of measures that are cruel and extrajudicial, if not outright barbaric. Tus, we must refresh our view of populace and resource control measures with the behaviors of a willful occupier with few self-limiting, ethical bounds.03

populace and resources control – Operations which provide security for the populace, deny personnel and materiel to the enemy, mobilize population and materiel resources, and detect and reduce the effectiveness of enemy agents. Populace control measures include curfews, movement restrictions, travel permits, registration cards, and resettlement of civilians. Resource control measures include licensing, regulations or guidelines, checkpoints (for example, roadblocks), ration controls, amnesty programs, and inspection of facilities. Most military operations employ some type of populace and resources control measures. Also called PRC.

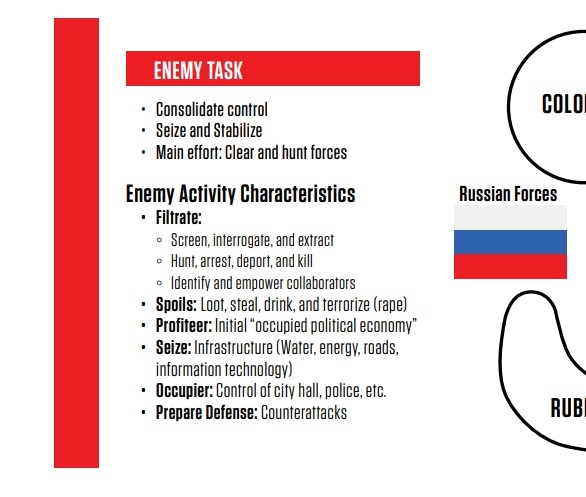

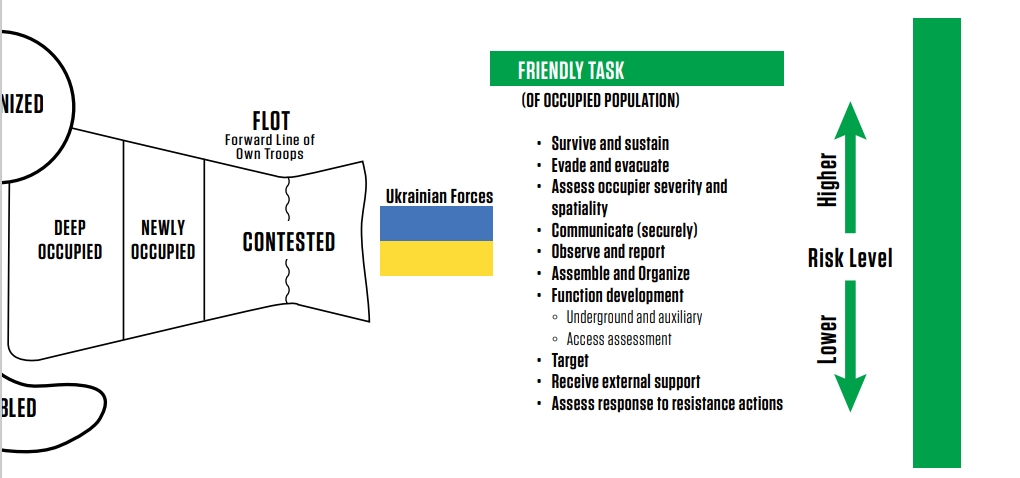

OCCUPATION TEMPLATE: NEWLY OCCUPIED

NEWLY OCCUPIED

Newly occupied areas are those areas where the invader has broken the defensive lines and seeks to consolidate control and extinguish resistance. In newly occupied areas, the occupier is only beginning to understand what it possesses, what it must investigate (clear), and how it might exert control. In this condition, occupier normative behaviors are neither established nor understood by the population. Occupying forces still have a direct combat mentality. Tey are less contemplative about viable occupation methods and more prone to escalate and retaliate with force if resistance is suspected or detected. Instilling fear into an occupied population is a method with limitless tactical expressions. It can also become self-defeating. Tis is the “occupier’s dilemma.”

New occupiers might be observed experimenting with what mixture of repression and coercion (sticks) versus methods of persuasion and cooperation (carrots) will be most efective. On the Eastern Front during World War II, the German Wehrmacht were faced with managing the vast, conquered lands and populations of Belorussia, Ukraine, and interior Russia. Te Wehrmacht struggled to reconcile brutal repression tactics with cooperative strategies. 04Despite its stated policy of brutal repression and widespread practice of such, some commanders sought out sensible arrangements with occupied peoples.055 Tis was not a charitable gesture; it was a transactional and relational calculation on how to best efect rear area security using fewer forces spread over vast lands.

Conceptually, but not dogmatically, the newly occupied period lasts from one day to one year. One year represents a four-season cycle of occupier inhabitation and regulation of civic life. Tis becomes particularly relevant in locales, where “fghting seasons” are common or in places like Ukraine that experience drastic seasonal changes. In this frst year, a key task for the invader is to shift control from the military and temporary hold forces to a sustainable security and governing system. It should be noted that the U.S.-led coalitions in Iraq and Afghanistan never mastered their environments despite technological overmatch, competent forces, indigenous partners, and time (measured in decades).06 To be sure, stabilization forces and occupying forces have diferent mandates, but the task list has many similarities.

For the occupied peoples, newly occupied space ofers both opportunity and catastrophic risk. Before an invader can establish its governing norms and enforce its directed behaviors, the environment is unstructured and, therefore, unpredictable. Tis environment presents the most difcult decision for a potential resistor—should I stay, or should I go? 077 In occupied Ukraine, Russia employs thorough and brutal fltration methods to detect, detain, or kill resistance actors. Alternately, if resistors displace to a safer haven to avoid fltration, they may fnd later re-infltration too difcult.

Figure 2 highlights some components of the newly occupied space in Ukraine. Tese categories of enemy and friendly acts and actors, when further detailed, reveal the challenges and opportunities that such an environment ofers. One such example is Kherson, Ukraine. Occupied in February 2022, the Russians assessed they could govern and suppress, in tandem, enroute to full annexation of Kherson as an oblast (administrative region) of the Russian Federation. Te Russian formula failed on two accounts. First, the population was given just enough space to organize and resist Russian occupation, violently and nonviolently. 08Second, this newly occupied space teetered back into “contested space” when the Ukrainians judged, correctly, that a military operation could dislodge occupying Russian forces.09Te Ukrainians liberated Kherson from Russian control in November 2022. 10

Figure 2: Newly occupation characteristics Russia in Ukraine, 2022 to 2024. By Brian Petit

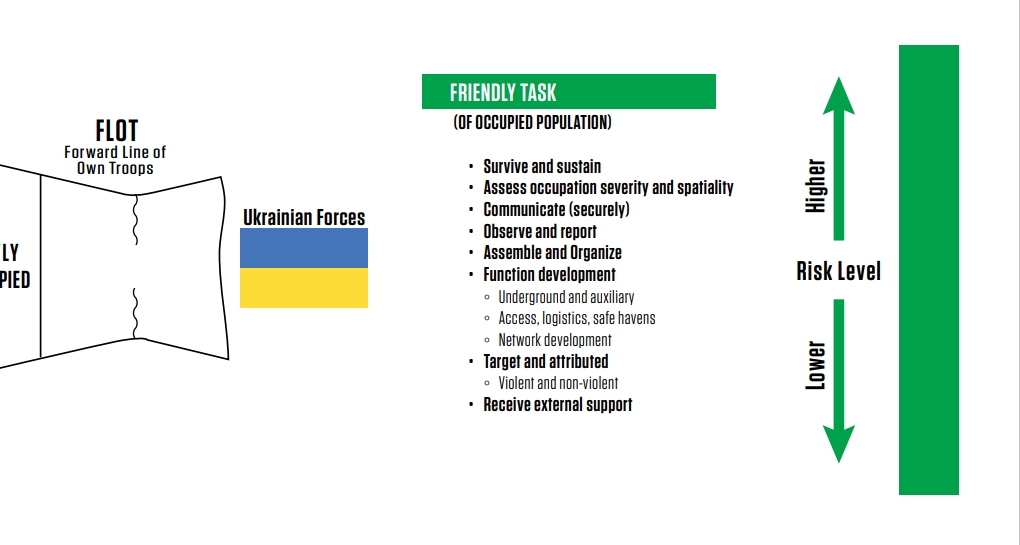

OCCUPATION TEMPLATE: DEEP OCCUPIED

DEEP OCCUPIED

Deep occupied space (fgure 3) combines a challenging geographical distance or formidable physical barrier and a time under-occupation period that suggests a settling normalization. One example is the Crimean Peninsula in March 2015, one year after the Russians fipped control without the use of large-scale violence. Here, the occupier is past the tipping point where large, surprise counterattacks can occur. Normalizing governance is underway. Te occupier confronts an occupied citizenry, who observe the new parameters and are forced to make a choice: fee, accommodate, collaborate, bide time, or resist. After a decade under occupation, Crimea nears a colonized status with full occupier control—willfully and systemically across—social, physical, and governmental domains.

Indicators of deep occupied space include new monetary units, technological infrastructure (internet, cellular towers) installed, social services provided, passports issued, security normalized (police, constabulary), as well as taxation, and education. 11 In newly annexed regions of Ukraine, Russia even changed the clocks, an unsettling signifer that even time itself was subject to occupier control. 12 2 Russian forces implement these control measures rapidly, often within weeks. Initially, these markers are more a psychological tactic than an exhibition of governing prowess. Tey are demonstrative signals of a new master and a rearranged order. Such new rules can also divide the population,as was the case of Ukrainian teachers who faced a stark choice between teaching a Russian curriculum in the Russian language or abandoning their students to some unknown fate. 13 Either choice was fraught with hazard, and otherwise reasonable Ukrainians found themselves in deep, even violent disagreement on this matter.

While deep occupied space suggests a less hospitable environment for resistance, the opposite may be true. Deep occupied space, with its settling normalization and routinization, may be the most fertile ground to conduct resistance operations. Tis is where the spatial measurements are telling. Deep areas may exist beyond the range of frst-person view drones, artillery, and front-line surveillance. A diferent type of platform exists here: people, technology, communications, mobility, and access. Te Ukrainian uptick in partisan, rear-area operations in late 2023 is illustrative. 14With limited maneuver options available and miles of mine-laden fronts, Ukrainian attacks in rear-areas presented lingering threats for Russians in deeply occupied territory. 15

IMPLICATIONS FOR ARMY SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES

Army special operations forces are uniquely designed, training, and equipped to support resistance movements. Without a proper understanding of the challenges facing our resistance partners, ARSOF risk misadvising on tactics, insufficiently organizing training, or making suboptimal procurement choices. Without regionally focused knowledge, militaries tend to toggle toward their own experiences and biases, as evidenced with the stabilization force challenges in Iraq and Afghanistan. Tese desert experiences provide insufcient mental models to contemplate how peer competitors occupy.

Figure 3: Deep occupation characteristics Russia in Ukraine, 2022 to 2024. By Brian Petit

The counter-occupation mission will continue to present unique challenges for ARSOF in the decades to come. As great powers like Russia and China bring technologically advanced forces, scale, frepower, proxies, and brutality to the equation, a more complete understanding is critical to ARSOF advisory eforts during counter-occupation. Te basic model presented in this article is part of the efort to shift the counter-occupation discussion from analyst cubicles to team rooms. In so doing, the force might narrow its knowledge gap, draw on its collective wisdom, and activate the creative minds of up-and-coming ARSOF leaders.

Endnotes

01. 1 US Army Field Manual 3-07.22 Counterinsurgency Operations, October 2004, Appendix C

02. 2 “Who Owns the Neighborhood? A Population and Resource Control (PRC) Handbook,” 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), Fort Lewis, WA, 2008 (Distribution Restricted); not an official publication.

03. David Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla (London, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013).

04. 4 Ben Shepherd, War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004).

06. Joel D. Rayburn COL and Frank K. Sobchak COL, The U.S. Army in the Iraq War – Volume 1: Invasion – Insurgency – Civil War, 2003-2006 (US Army War College Press, 2019), https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/386 Jeanne F. Godfroy, James S. Powell, Matthew D. Morton, and Matthew M. Zais, US Army in the Iraq War Volume 2

10. Institute for the Study of War, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” November 13, 2022.

14. Institute for the Study of War, “Special Edition Campaign Assessment: Ukraine’s Strike Campaign Against Crimea,” October 8, 2023

Author

Brian Petit is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel. He teaches and consults on strategy, planning, special operations, and resistance. He is a part-time adjunct for the Joint Special Operations University.