Integrating Drones Isn’t Intuitive:

Practical Ways to Build this Critical Capability

By LTC Reed Markham

Article published in the Fall 2024 Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time:

< 13 mins

Above, Soldiers in the 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment employ a commercial

off-the-shelf quadcopter during a training exercise. (Photos courtesy of author)

Flying robots that identify their enemy, drop grenades, bring fires, or suicide themselves to destroy armored

vehicles are commonplace in the Russia-Ukraine War. Drones have not only dramatically shaped that war, but they

have also been used by Hamas to set conditions for their terror attacks on 7 October 2023, the Azerbaijan

military to change the balance in the Nagorno-Karabakh War, and Iranian proxies in their attacks on U.S. naval

and ground forces.1-3 I pondered all

of this as I watched firsthand one “battlefield” where drones were not having any impact — my battalion’s

platoon live fires. This distressing fact was made apparent when the fourth straight platoon’s small unmanned

aerial system (sUAS), a minihelicopter called a Black Hornet, shakily lifted off, raised 10 feet in the air, and

then smashed into the ground. It became even more clear when the second unit in a row reported that its

company-level UAS system, a Raven, was unable to fly because of missing parts, an inexperienced operator, not

having the restricted operating zone (ROZ) activated at the right time, or some combination of those factors.

This was the moment that I fully understood that we had a problem and needed a new approach to integrating this

critical asset into how we fight.

To frame the problem appropriately, I did not assess that our battalion was the anomaly in struggling to

integrate drones. We have a great unit that is fortunate in the quality of its past and current officers and

NCOs. However, something was stopping us from saturating the battlefield with sensors as the current and future

battlefields demand.4 So, what was

the problem? Turns out there were many, and some we could affect, some we could not. We can’t control the number

and type of UAS we are fielded — just as you use the night vision devices, shoot the weapons, and wear the body

armor you are fielded. Many factors we could affect, however, and that is where we focused our energies. Our

leaders struggled to visualize drone employment, our operators weren’t experienced, and our training and

resourcing systems didn’t support the effort. During our quest to flood the zone with drones and radically

increase our warfighting ability, I identified three key areas that demanded improvement: We needed to train and

certify our leaders, provide hours and hours of flying repetitions and simple objectives for our operators, and

integrate UAS into the battalion-level training and maintenance management systems.

Visualizing the Battle

If you close your eyes, can you visualize swarms of drones in front of your forces conducting reconnaissance of

routes, various positions, obstacles, and the enemy to identify their command-and-control locations, indirect

fire assets, and antitank/ machine-gun positions? Picture fire supporters making micro adjustments to their

pre-planned targets before massing fires to overwhelm and destroy the enemy... or assault leaders and sappers

pinpointing the location of the breach and the positions they will bound their elements to preserve their forces

and close with and destroy the enemy. How about drone operators identifying a remaining enemy machine-gun

position in a trench, dropping a 40mm round on it, and then reporting that key condition is met before the

assault element advances? Lastly, visualize immediately after the attack, when transitioning to the defense,

rapidly sending drones along the most likely avenues of the enemy’s counterattack to enable indirect fires to

disrupt and the now-rightfully placed antitank weapons and machine guns to destroy. Can you see the battle that

way?

Well, I couldn’t, nor could most of our leaders. We had to start with casting a shared — and easily understood —

battlefield vision for the leaders in the battalion. Every element in the battalion would use drones: rifle,

heavy weapons, scout, mortar, and distribution platoons as well as all command posts. Our drones would:

1.

Recon our routes, positions, obstacles, and the enemy;

2. Deceive and disrupt the enemy;

3. Integrate

fires and drop munitions; and

4. Secure our forces.

Current UAS Training Resources

The Army has some helpful doctrine to direct the training and employment of drones. One source we used to

determine offensive uses of drones was the Army’s counter-UAS doctrine, Army Techniques Publication (ATP)

3-01.81, which was very helpful in defining missions, UAS groups, and the basic logic of their use.5 However, not all the doctrine has

kept up with the advances since the Russians escalated their attack deeper into Ukraine. My assessment is that

Training Circular (TC) 3-04.62, Small Unmanned Aircraft System Aircrew Training Program, written in 2013, was

developed for the fixed-wing sUAS (Raven), and the requirements for operator and program training, tracking, and

currency seem too stringent and slow to keep up with the current commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) quadcopter

variants.6

There are some helpful existing training and program-tracking systems. Ensuring operators use drones inside a ROZ

and are trained on basic employment through the online basic unmanned qualification course is critical.7 We also logged operators’ flight

hours inside the sUAS manager to identify future master trainer candidates and help us track our proficiency.

However, to make tangible gains in the employment of UAS in collective training, live fire, and situational

tactical exercises, we needed to ensure we did not overdo UAS programming at the expense of actual combat

capability. Fighting with drones is vitally important now; we cannot afford to overcontrol it to mitigate risk

at the expense of real implementation.

Once we understood our current situation, envisioned future, and resources available, it was time to act and

build a real, lethal, and lasting drone capability.

Fighting with drones is vitally important now; we cannot afford to overcontrol it to mitigate risk at

the expense of real implementation.

Training Leaders

We had to train our company- and platoon-level leaders on the new vision of the battlefield. Our platoon leaders

and sergeants balance many things early in the Army. Integrating and synchronizing the foundations of a rifle

platoon, its machine guns, anti-tank systems, rifle squads, and external mortars is challenging enough. Now they

must rapidly learn to employ the awesome, but complicated, integrated tactical network (ITN) to populate their

position location information and receive, make, and rapidly disseminate digital graphics on their end user

device through the android team awareness kit (ATAK). Our digital fires systems also allow quick integration of

artillery and adjacent unit mortars into their operations. Throw drones on top and even our most talented young

officers and NCOs will struggle without deliberate training.

To train our platoon-level leaders, we found that starting with a white board to sketch out the drone battlefield

vision helped them share that understanding. Giving them simple tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) was

important. For example, treat the UAS operator as a member of the platoon headquarters element, same as their

radio-telephone operator (RTO), forward observer (FO), and medic. That way the operator can move back and forth

between the platoon leader and platoon sergeant based on aspects of the operation while maintaining the right

leader oversight of the drone employment. Lastly, we trained our leaders by providing a mental model of when to

employ the drone and how that fits within the normal stages of executing an operation (for example, at the

objective rally point, before reaching the assault position, immediately after reaching the limit of the advance

of the attack, etc.).

Our Army is great at integrating and echeloning indirect fires. Fire supporters and our maneuver leaders are

trained on this critical task through fire support team certifications, call-for-fire trainers, collective

training, and fire support coordination exercises. Based on the depth of knowledge of the mental model of

echeloning fires, we trained our leaders to integrate UAS using the same structure. Doing so during planning and

rehearsals was critical to ensuring UAS were built into indirect fires planning as a tool for observers to

initiate the various artillery a nd mortars.

During the planning phase, our leaders identified the right locations to launch the various drones. For example,

drones such as Skydios and DJI Maviks can be launched from 2-3 kilometers away, fly a deceptive route, and

conduct their recon mission, all while the platoon is still moving towards the objective to then receive the

drone at a different landing location. Once closer to the enemy, the platoon can fly its Soldier Borne Sensor

(SBS) Black Hornet using the quick “periscope” method of rising above the tree line to gain a final assessment

of the enemy while our forces remain behind cover. Finally, before or during the assault, DJI Maviks or Skydios

with fabricated munition droppers attached can execute precision attacks on enemy fighting positions or trenches

where direct fire weapons struggle to achieve lethal effects. Simple engagement criteria to operators enables

initiative (for example, find antennas or machine guns and kill them). Once our leaders visualized drone

integration into the battle using the model of echeloning fires, we were able to effectively account for them

during planning and execution.

Platoon headquarters elements consisting of a platoon-level leader, radio-telephone operator,

forward observer, and unmanned aerial system operator work together to command and control the platoon.

Training Expert Operators

Nearly 2,500 years ago, Archilochus was probably not talking specifically about flying robots to recon and drop

bombs on the enemy, but his words hold true: “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the

level of our training.” Leaders understanding how to employ drones is not enough without trained, confident, and

knowledgeable UAS operators. Repetition, repetition, repetition — it’s the key in bowling, shooting a basket,

running a maintenance meeting, crewing a machine gun, and yes, flying drones.

You probably heard, as I did, that our Soldiers, especially the gamers, will instinctively pick up the flying of

these drones. I found that 100-percent false. As with anything, time varies by Soldier, but our rough estimate

is operators need to fly around 10 hours to not be a liability in the operation and around 15 hours before they

seamlessly integrate the UAS into the platoon’s operation. Adding a ROZ in every event and creating frequent

flying opportunities for our operators were both critical to building their experience and confidence.

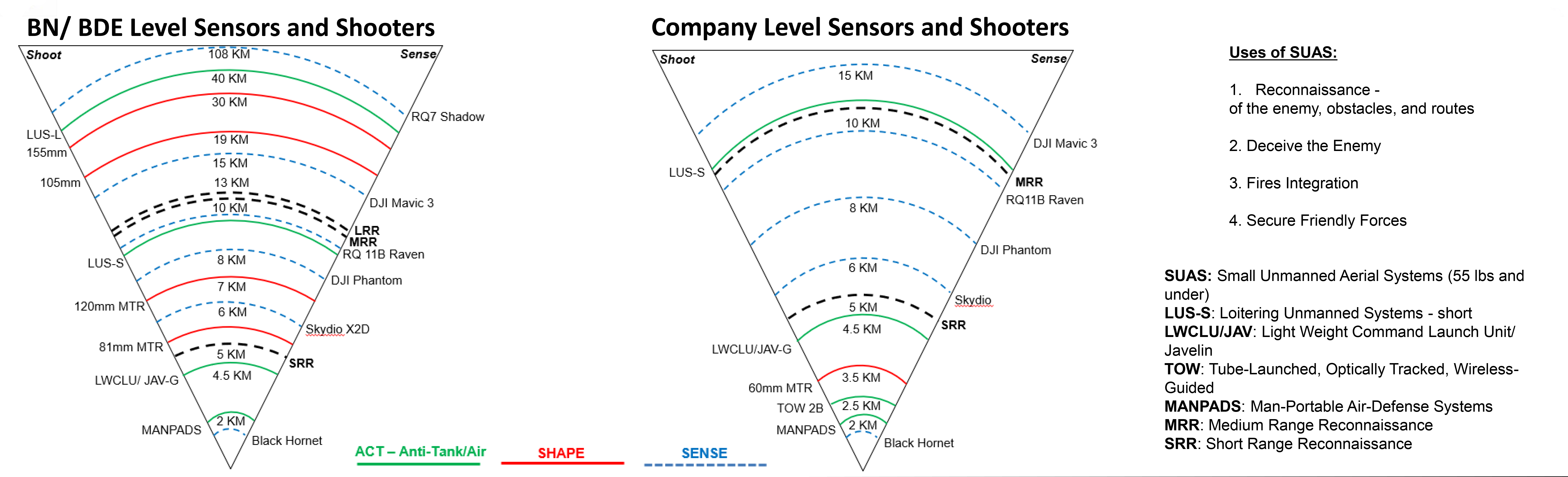

Figure 1 — Echeloning the Employment of Indirect Fire, UAS, Anti-Tank, and Air Assets

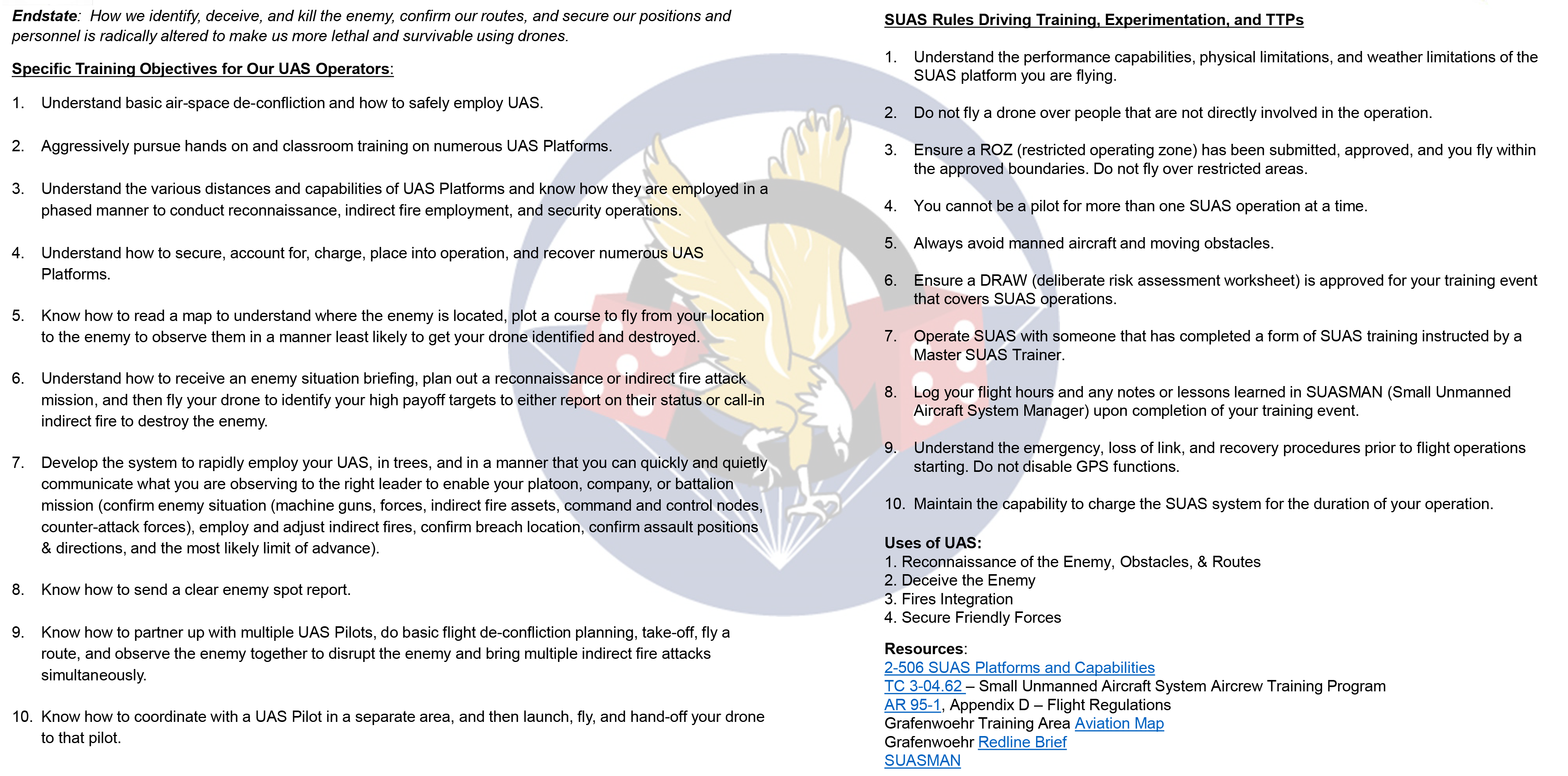

Just as we needed a shared vision for employment by leaders, the same was true for our operators. Creating plain

speak — jargon and acronym free — training objectives and rules for our Soldiers provided them a knowable

training path (see Figure 3). For example, placing the drone into operation, developing a simple flight path,

and using identifiable terrain features to quickly deconflict air space with other drones gave tangible actions

for our operators. This also helped reinforce proper use by leaders. As in most of our war-fighting training,

hands-on training using simple guides was more effective than the hours of an online basic unmanned

qualification course or in-person classroom instruction using PowerPoint.

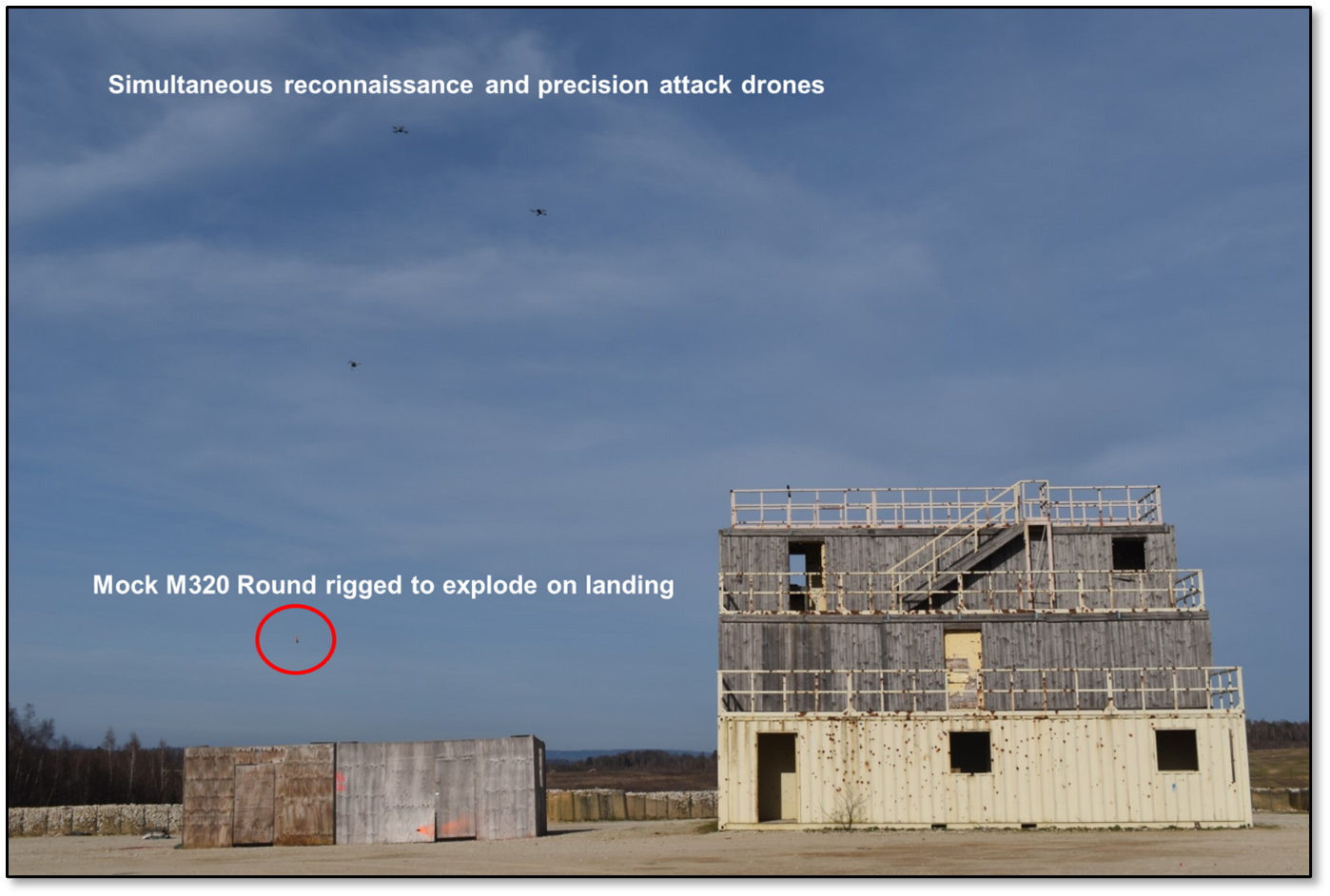

Figure 2 — Example Exercise with COTS Drones Employing Reconnaissance and Precision Attack

Capabilities

Manning a machine gun or a tank is a team sport; the same applies for launching robots into the sky. Instilling

the crew mentality to the employment and recovery of UAS assisted in the speed, safety, and the preservation of

our systems. We learned this lesson the hard way after numerous failures or too slow launches, and worse,

breaking hard-to-replace antennas as a flustered operator yanked a $12,000 drone out of his assault pack.

Integrating the platoon’s RTO, FO, and medic into the UAS “crew” helped decrease launch and recovery time and

led to more effective tactical transport of the systems. There were also hard-to-quantify advantages to getting

more Soldiers involved in drone employment that led to smoother integration.

Figure 3 — Plain Speak UAS Operator Training Guidance and Rules

Building UAS Enabling Systems

Systematizing an activity helps to weight the effort appropriately. We found adding drone employment to our

battalion training resource meeting made an outsized impact. When our drones were just another system sitting in

a tough box dependent on the individualized efforts of the high-speed operator or innovative leader, we had

sporadic successful employment. Once we added the issuing of UAS and requesting of a ROZ as critical items for

each training event — the same as ammunition and land — we were able to increase training opportunities. Events

that were not normally viewed as times to integrate UAS, such as crew qualification and land navigation, became

occasions for operator repetitions and TTP development. Adding our drone status to our maintenance meeting was

also key to forcing us to work through how to repair or coordinate replacement of non-standard equipment.

Deliberate recovery operations with company drone status reporting allowed us to better see ourselves and get

broken systems fixed. What we track and report on is how we prioritize efforts, and we were unable to weight

this effort effectively until we integrated UAS into the battalion’s core systems.

COTS drones, although easier to use than the Raven or Puma, require expert operators to

rapidly employ in tactical situations.

Recommendations

• Battalion leader development programs account for training platoon-level leaders on how to employ sUAS, similar

to how we train our leaders to integrate fires. • Battalion training resource systems establish ROZs at every

training event, pool the sUAS in the unit, and ensure their maintenance status and allocation to every unit’s

training. • Leaders, all of them, fly drones, not because they have to become experts, but understanding the

basic employment allows more effective integration, similar to how every fighting leader can employ all the

weapons assigned to his or her unit. • Companies build a bench of trained UAS operators (we have a minimum of

eight per company). This allows continuity, spreads the knowledge of employment throughout the ranks, and drives

innovation as the incredible creativity of our Soldiers is identified and unleashed. • Every unit trains with

sUAS — we do not recommend consolidating the systems with the scout platoon as that risks their integration into

every aspect of a unit. • sUAS is fought as a crew (not necessarily Soldiers’ primary or only duty); we have an

assigned primary duty UAS operator supported by the RTO, FO, and/or medic at our company and platoon

headquarters.

Drones are not just the future of warfare; they are the present. Unlike the Ukrainians, we do not have the

stimulus that drives battlefield innovation from the level of violence and desperation existing in war. We

cannot afford to wait until that happens to develop the training and employment techniques with this vital new

asset. Our Army will not use drones exactly the way others are employing them. Many units employing UAS in many

ways will create an environment where the most practical and effective uses flourish. There are more obstacles

to employing UAS; however, training leaders to understand how and when to employ them, building expertise with

operators, and adjusting existing systems to maintain and resource our UAS efficiently are ways to integrate

this critical asset into a unit. I am certain there are more and look forward to learning better ways to do so!

Drones are not just the future of warfare; they are the present... Our Army will not use drones exactly

the way others are employing them. Many units employing UAS in many ways will create an environment where the

most practical and effective uses flourish.

Soldiers in 2-506 IN employ a drone in a crew manner at night.

Notes

1. Eado Hecht, “Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh War:

Analyzing the Data,” Military Strategy Magazine 7/4 (Winter 2022), https://www.

militarystrategymagazine.com/article/drones-in-the-nagorno-karabakh-waranalyzing- the-data/.

a>

2. Mia Jankowicz, “How Hamas Likely Used Rudimentary Drones

to ‘Blind and Deafen’ Israel’s Border and Pave the Way for its Onslaught,” Business Insider, 10 October

2023, //www.businessinsider.com/hamas-dronestake- out-comms-towers-ambush-israel-2023-10.

3. Rodney Barton, “The Use of Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh

Conflict,” Australian Defence Business Review, 24 May 2021, https://defense.info/

air-power-dynamics/2021/06/the-use-of-drones-in-the-nagorno-karabakhconflict/.

4. GEN James Rainey and LTG Laura Potter, “Delivering the

Army of 2030,” War on the Rocks, 6 August 2023,

https://warontherocks.com/2023/08/ delivering-the-army-of-2030/.

5. Army Techniques Publication 3-01.81, Counter-Unmanned

Aircraft System (C-UAS), August 2023, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/ DR_a/ARN38994-ATP_3-01.81-000-WEB-1.pdf.

6. Training Circular 3-04.62, Small Unmanned Aircraft System

Aircrew Training Program, August 2013,

https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/ DR_a/pdf/web/tc3_04x62.pdf.

7. U.D. Defense, SUASMAN, retrieved from Small Unmanned

Aircraft Systems Manager,

https://suasman.sofapps.net/Site/Home.

Author

LTC Reed Markham is an active-duty Army officer since 2005 who has led and trained Soldiers from the platoon

through battalion level. LTC Markham is currently in command of 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment, 3rd

Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, KY.

1LT Jonathan Dow is the 2-506 IN battalion editor and greatly contributed to this article.