Army Medicine

Saving Lives Since 1775

By Dr. Sanders Marble, AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Maj. Lamanda Jackson

Article published on: May 1st, 2025, in the May 2025 Issue of The Pulse of army Medicine

Read Time: < 7 mins

On this day 250 years ago, the Continental Congress authorized the creation of “an hospital” to care for the troops of the new Continental Army. Interestingly, the decision came six weeks after the Continental Army itself was established, prompting the question: what caused the delay? The answer consists of four main reasons: lack of patients, lack of awareness of the impact of battle casualties, lack of support for non-local troops, and lack of the ability to expand operations.

First, the lack of patients created little need for a troop hospital. The local facilities were presumably adequate, and militiamen could be sent home if needed. However, the sanitation problems the armies had soon drove the need for a hospital. The longer the Army camped around Boston, the more sick Soldiers there would be.

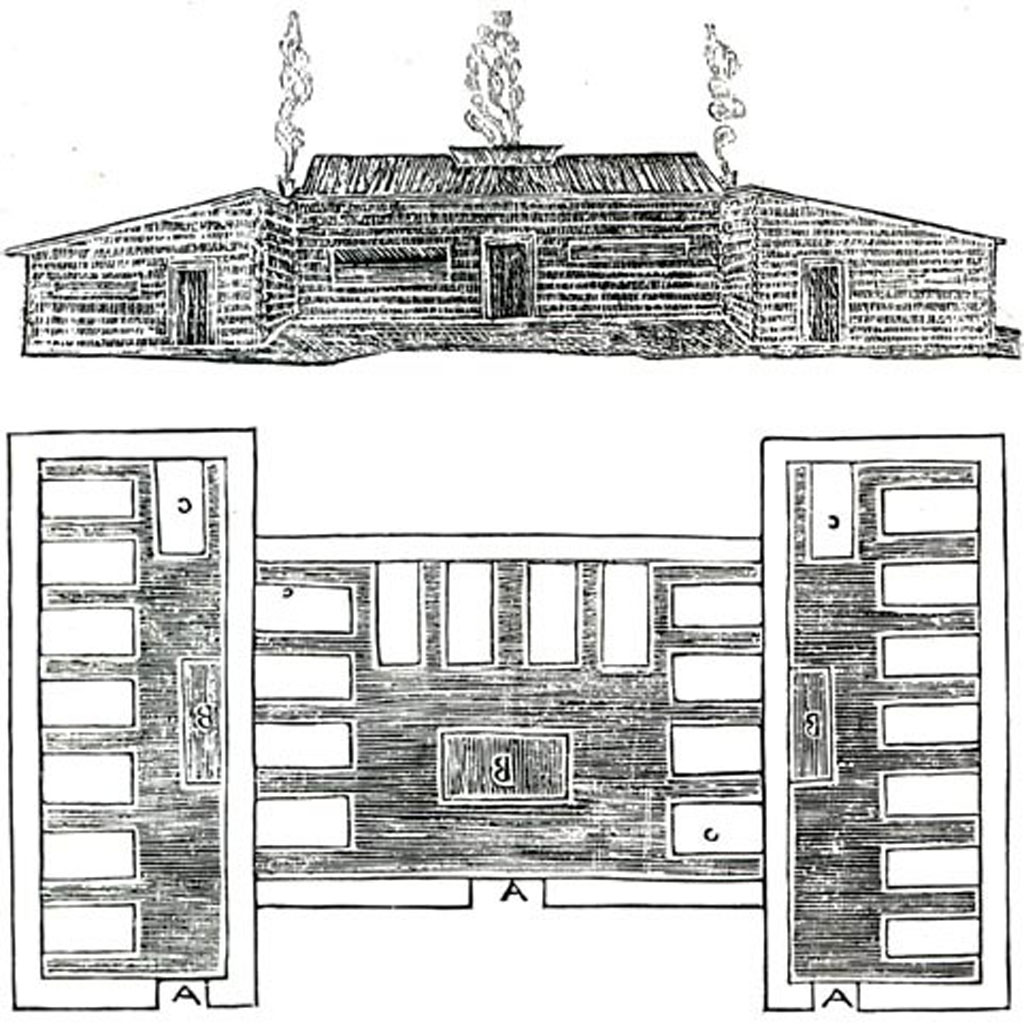

There were only two hospitals in the American colonies before the revolution; most people received medical care at home. The Continental Army used schools, churches, homes, and other buildings as improvised hospitals. However, poor ventilation often caused disease to spread. Dr. James Tilton (who was Surgeon General of the Army during part of the War of 1812) designed a hospital building with better ventilation. Image courtesy National Library of Medicine.

Second, unit medical staff could be swamped by battle casualties. Between June 14 and July, the Battle of Bunker Hill demonstrated the realities of battle casualties, engaging one-fifth of the force and leaving units in dire need of additional support.

Third, there was no support for non-local troops. As Soldiers from further away arrived, they would not have local support and would need pay and authority beyond what Massachusetts could provide.

Fourth, the local support stayed local; unfortunately, operations continued to expand across the colonies, driving the need for expanded medical care across the entire region.

George Washington immediately recognized the commanders’ responsibility for troop health. The day after he took command of the Continental Army, he ensured smallpox hospitals were properly quarantined to limit the spread of disease. Ten days later he emphasized that “the Health of an Army principally depends upon Cleanliness” and issued orders about the necessity of clean latrines, barracks, and kitchens. He also asked the Congress to organize medical care because “the Lives & Health of both Officers & Men, so much depend upon a due Regulation of this Department.”

Through the Revolutionary War, doctors struggled to care for troops, conserving health, treating the sick, performing surgery, and offering psychiatric services. None of the aforementioned had progressed much beyond ancient texts from Greece and Rome. Recently, European armies had developed concepts of how medical support could sustain combat strength, but almost nobody in the colonies had read those works. There were few physicians, and even when augmented by apothecaries and others, their treatments likely did more harm than good. The exception was inoculation against smallpox, and troops sought inoculation. In fact, the lack of inoculation deterred enlistment.

James Thacher had just completed his medical training in 1775, age 21, and joined the 16th Massachusetts Regiment as surgeon’s mate. Serving until 1781, he saw action in several battles and many of the camps and hospitals of the war. Image courtesy National Library of Medicine.

From the earliest campaigns of the Revolution to the vital battle at Yorktown, doctors tried their best. They suffered alongside patients. In fact, doctors had a higher death rate, doubtless due to prolonged exposure to disease and showed their dedication to cause and patients. Many times they failed, but not through failing to try. Dr. James Thacher treated patients – friendly and prisoners – after the battle of Saratoga. Afterwards, he noted, “Amputating limbs, trepanning fractured skulls, and dressing the most formidable wounds, have familiarized my mind to scenes of woe. A military hospital is peculiarly calculated to afford example for profitable contemplation, and to interest or sympathy and commiseration. If I turn from beholding mutilated bodies, mangled limbs, and bleeding, incurable wounds, a spectacle no less revolting is presented, of miserable objects languishing under afflicting diseases of every description – here, are those in a mournful state of despair, exhibiting the awful harbingers of approaching dissolution – there, are those with emaciated bodies and ghastly visage, who begin to triumph over grim disease and just lift their feeble heads from the pillow of sorrow…”

Because surgeons lacked modern implements, and imaging equipment, they used metal probes and even fingers to find musket balls and bone fragments in wounds. Today a soldier has a tourniquet, some medics use an endovascular balloon in the aorta to stop chest hemorrhage, and a battalion surgeon can use a portable ultrasound to assist their efforts. In 2275, today’s techniques may look as primitive as the ones in 1775, but doctors then were bringing the best medical capabilities of the time to the hospital and the battlefield.

Surgical sets of the period lacked many modern tools. This set was probably used in the American Revolution, and was certainly used in the War of 1812. Image courtesy National Museum of Health and Medicine.

While they did not yet fully understand viruses and bacteria, they understood prevention. Benjamin Rush advised “Too much cannot be said in favour of Cleanliness. If soldiers grew as speedily and spontaneously as blades of grass on the continent of America, the want of cleanliness would reduce them in two or three campaigns to a handful of men. It should extend, 1. To the body of a soldier. He should be obliged to wash his hands and face at least once every day, and his whole body two or three times a week, especially in summer. The cold bath was part of the military discipline of the Roman soldiers, and contributed much to preserve their health. 2. It should extend to the clothes of a soldier. Frequent changes of linen are indispensably necessary; and unless a strict regard is paid to his articles, all our pains to preserve the health of our soldiers, will be to no purpose, 3. It should extend to the food of a soldier. Great care should be taken that the vessels in which he cooks his victuals should be carefully washed after each time of their being used. … The environs of each tent, and of the camp in general, should be kept perfectly clear of the offals of animals and of filth of all kinds. They should be buried or carefully removed every day beyond the neighbourhood of the camp.”

The troops of the Continental Army wanted medical care. Even ineffective care sustained morale: someone cared for them, and it showed their country cared about them. Congress knew “an Hospital” could sustain the troops, and units not burdened with sick and wounded could maneuver, fight, and win.

From Battlefield Amputations to Robotic Surgery: Military Medicine Today

Today, 250 years since the Continental Army’s first “hospital” was approved, what began as a valiant endeavor into military medicine has developed into an advanced, high-tech endeavor to saves lives. Over the centuries, we have attended to medical needs in ways that our predecessors could not have predicted.

A medic uses a handheld tactical telemetric device in the field. Portable diagnostics and telemedicine allow rapid decision-making in combat zones, saving lives and limbs. Image courtesy DVIDS.

Medical units are now equipped with small, portable diagnostic tools, such as field X-ray systems and handheld ultrasound devices. These devices enable doctors and surgeons to make prompt decisions in the field. Combat medics use a technique called Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta, or REBOA, to stop internal bleeding from the pelvis and abdomen, which was once very lethal in combat.

The advancement of telemedicine also allows military physicians to reach a larger audience worldwide. Forward medics can now consult with neurologists or trauma surgeons in real time from geographically separated outposts. This capability has been tested and validated in recent deployments and humanitarian missions where Army physicians provided care in isolated areas with limited infrastructure.

Technological advancements also continue to improve patient care. The use of robotics enables surgical precision, and AI provides rapid diagnostics and better monitoring capabilities. Additionally, initiatives like the Medical Research and Development Command provide innovations such as next-generation vaccines, synthetic blood substitutes, and regenerative medicine. This continued investment in the next generation of combat casualty care ensures the Army remains at the forefront of medical innovation.

From the muddy hospitals of 1775 to the high-tech trauma bays of today, Army medicine has always been about one thing: keeping Soldiers in the fight and returning them home. It is up to us to be as committed to the cause of liberty—and to each other—as our forefathers were.