A Mission Command Meditation: Intelligence Intent and Guidance

By Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Fontaine

Article published on: January 21, 2024 in the Military Intelligence January–June 2024 Issue

Read Time: < 18 mins

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21236/AD1307177

This article is part one of a two-part series on employing mission command within the intelligence warfighting function.

Introduction

Commanders personally drive the operations process using the mission command approach; the best ones do, anyway. The increasing lethality of the modern battlefield, primarily from the proliferation of novel or advanced information collection systems combined with more capable long-range precision fires, will place an ever-greater premium on competent leaders who provide timely intent and guidance, drive processes, and empower their dispersed subordinates to make decisions and accept risk.1 The mission command approach demands personal involvement in the military decision-making process and during all planning stages.

Just as commanders must drive the operations process, senior intelligence officers must intuitively co-drive the intelligence process with commanders during the execution of dynamic large-scale combat operations. (Doctrinally, the commander drives both the operations and intelligence process.)2 The days of the senior intelligence officer having the luxury to oversee assembly line-like intelligence production within a large command post are in the past.

Senior intelligence officers must meditate on their role and the ways they can uniquely contribute to assist commanders in driving the intelligence and operations processes. Senior intelligence officers can maximize their value if they—

- Embrace the mission command philosophy.

- Sense intuitively and act appropriately.

- Build sensemaking capabilities.3

The Primary Role of the Senior Intelligence Officer

During war, the Army expects its commanders to “drive the operations process through the activities of understanding, visualizing, describing, directing, leading, and assessing operations.”4 The staff’s part in the commander-centric operations process “is to assist commanders with understanding situations, making and implementing decisions, controlling operations, and assessing progress.”5 The senior intelligence officer’s primary role is to “provide the commander the most complete and timely intelligence available. . . . that enable[s] commanders to make timely and relevant decisions.”6

The senior intelligence officer must execute two simple functions to accomplish their primary role during operations. First, the senior intelligence officer must communicate the most complete and relevant intelligence available directly (face-to-face) or electronically to the commander. Second, for it to be timely, the information transmitted must keep pace with the commander’s decision-making process–preferably, well ahead of changing conditions on the battlefield. It sounds simple, but as Carl Von Clausewitz reminds us, “everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult.”7

The Future Battlefield

New or forecasted adversary capabilities and anticipated conditions of the future battlefield will challenge the senior intelligence officer’s ability to execute their primary role. The increasing threat of enemy precision or massed long-range fires against command posts will necessitate greater tactical dispersion of forces.8 Senior intelligence officers cannot expect to direct all elements of the intelligence cell in person at one geographic location or to have routine face-to-face contact with the commander at a command-and-control node.

Our adversaries can contest electronic communications, meaning Army forces must be capable of operating in denied, degraded, intermittent, and low bandwidth environments.9 Senior intelligence officers must plan for disrupted communications rather than a continuous flow of intelligence. They will have to adapt to a future of periodic updates from the intelligence cell.

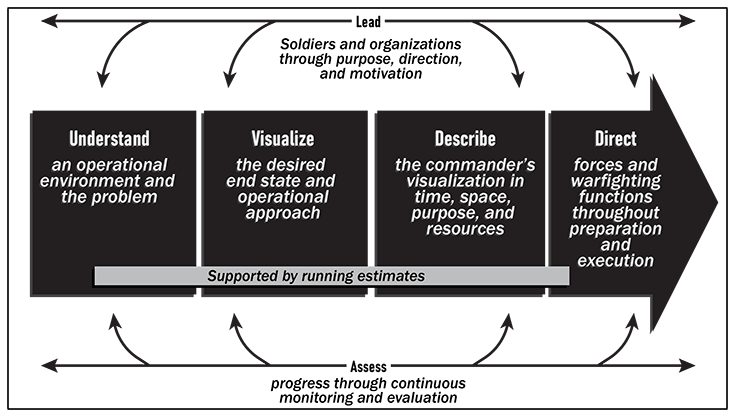

Furthermore, large-scale combat operations are inherently high-tempo, uncertain affairs where conditions can change rapidly, and leaders will struggle to keep pace.10 Modern sensors further compound the mental bandwidth challenge. These sensors provide an “increasingly powerful firehose of data” capable of overwhelming the senior intelligence officer and intelligence cell’s processing capability.11 Despite these challenges, the senior intelligence officer must support the commander’s activities to understand, visualize, describe, direct, lead, and assess operations while also seizing opportunities to effectively mitigate risks.12 See figure below.

If the senior intelligence officer cannot communicate electronically or transmit data to the commander, they must be with the commander. Commanders must “assess the situation up front as often as possible,”14 so the senior intelligence officer should also operate and lead from up front. This arrangement is nothing new. What is new is the contested communications environment, the risk of destruction when emitting an electromagnetic signal, and the increased requirements of tactical dispersion. In this operational environment, the senior intelligence officer must know and understand the complete intelligence picture because when forward with the commander, there is no guarantee that communications with subordinate intelligence personnel will be possible. The senior intelligence officer must also develop effective ways to lead, guide, and collaborate with the intelligence cell in this challenging environment. They will find themselves in an unenviable position—required to provide the commander with relevant intelligence in a rapidly changing situation with contested access to their dispersed analytic bench that is processing ever greater feeds of data.

The commander’s role in the operations process13

Fully Embrace the Mission Command Philosophy

To overcome the anticipated challenges of large-scale combat operations, the senior intelligence officer must adapt how they lead by fully embracing the mission command philosophy. One way they can uniquely influence the intelligence process is by adopting and modifying mission command tools long used by commanders: the commander’s intent and planning guidance. However, before we can discuss the intersection of mission command philosophy with the intelligence warfighting function, we must first understand the commander’s unique role within mission command and the importance of competence.

Mission command empowers subordinate leaders to take the initiative in dynamic situations where dialogue with the commander is not possible and to act within the boundaries of the commander’s intent to accomplish the desired end state.15 The mission command philosophy’s emphasis on intent and initiative makes it particularly advantageous to overcoming the challenges faced in war. Its successful implementation requires a high degree of leader and team member competence.16

Highly competent Army leaders provide and align “purpose, direction, and motivation” among their subordinates.17 Using the mission command approach during large-scale combat operations, a commander codifies purpose and direction in their intent, which is doctrinally defined as “a clear and concise expression of the purpose of an operation and the desired objectives and military end state.”18

The commander typically issues planning guidance in addition to their intent, key tasks, and end state.19 Planning guidance provides the commander’s approach to the mission, may outline initial courses of action, and “reflects how the commander sees the operation unfolding.”20

Critically, commanders “often address conditions for transition” to spur planning for follow-on operations within their intent.21 The commander’s intent and guidance ensures the mission can continue even if communications become degraded, command posts are destroyed, or the commander is incapacitated.22

Subordinates expect their leaders to provide purpose, direction, and motivation. The obligation of leadership underscores why the commander’s intent and planning guidance is so important. It is the commander’s unique means to communicate with subordinates and staff their vision for accomplishing the unit’s objectives. It is something only they can provide. If these mission command tools are so powerful, isn’t it time for senior intelligence officers to fully leverage them within the intelligence warfighting function?

The Senior Intelligence Officer’s Intelligence Intent and Guidance

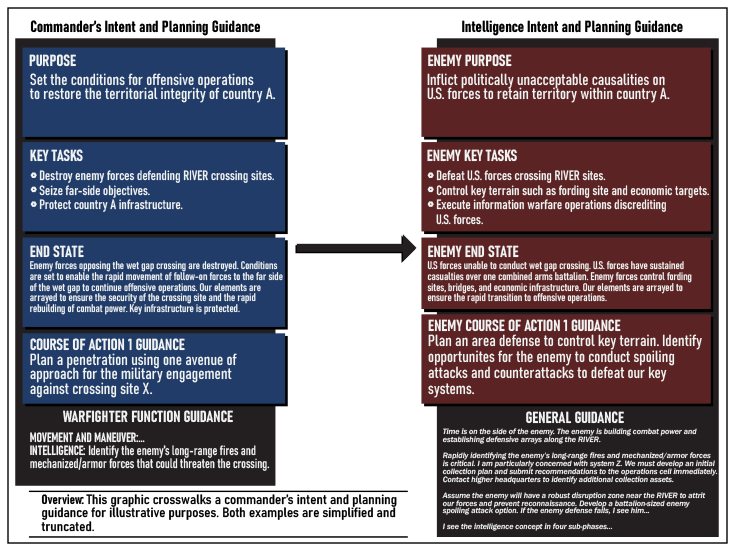

Senior intelligence officers can take the commander’s intent and planning guidance to produce something I will label the intelligence intent and guidance. This is a concise, structured addendum to the commander’s intent and planning guidance that adds additional depth and clarity specific to the intelligence warfighting function based on the senior intelligence officer’s experience, judgment, and expanded access to the battlefield and senior leaders. It complements the commander’s intent and planning guidance and is a nested staff version of what subordinate commanders do after receiving their higher headquarters end state. The intelligence intent and guidance is the senior intelligence officer’s tool to conceptually frame topics, such as the concept of intelligence for the operation, anticipated enemy options or transitions, and collection guidance.

The Purpose. While the information in the intelligence intent and guidance may change, its purpose remains the same. The intelligence intent and guidance should—

- Ensure unity of purpose within the intelligence warfighting function, even if tactical dispersion and limited communications reduce interaction between the senior intelligence officer and the intelligence cell.

- Enable better and more rapid integration and synchronization of intelligence and collection assets.

- Incorporate the senior intelligence officer’s experience and often unique situational awareness.

- Serve as a common point of reference that is easy to update during degraded communications between the senior intelligence officer and the intelligence cell.

- Guide future intelligence activities to support disciplined initiative if the situation (or plan) deteriorates and contact with the senior intelligence officer is impossible.

- Set the conditions to “predict, preempt, or prevent” enemy action.23

Ten Questions. The 10 questions are a way to rapidly examine the commander’s intent and planning guidance and develop the intelligence intent and guidance. It includes any initial thoughts on predicting, preempting, or preventing the enemy action most likely to place the unit at risk of not achieving its desired end state. The intelligence intent and guidance should provide a concise visualization and written narrative of what the enemy is doing, will do, and could do because of friendly actions. Key intelligence intent and guidance components should address these 10 questions:

- What is the enemy doing now?

- What is the enemy commander’s intent, key tasks, and end state?

- How might the enemy commander achieve their desired end state in the immediate to near term?

- What could the enemy commander and higher headquarters do to improve their chances of success in the immediate to near term? Identify options and branches.

- What will the enemy commander and higher headquarters do if they fail to achieve their objectives? Identify sequels. For example, failure options.

- What will the enemy commander and higher headquarters do if they achieve their objective? Identify sequels. For example, exploitation options.

- How will the other METT-TC (I) factors influence enemy and friendly decisions?24

- How might the enemy react to friendly force actions in pursuit of the commander’s end state?

- What is peculiar about the enemy, friendly forces, or situation that could influence future events?

- What if we are wrong? Provide an alternate analysis of the situation.25

When answering these 10 questions, the senior intelligence officer, in conjunction with the rest of the staff, identifies potential indicators or high-value targets to kickstart information collection. They also consider any enemy action likely to earn a “most dangerous” moniker during intelligence preparation of the operational environment26 that would require immediate collection. Finally, the senior intelligence officer must define “near term” according to their situation (for example, the next 0 to 72 hours). As with the commander and their intent, the senior intelligence officer modifies their guidance based on input from the intelligence cell and as the situation develops.27

Intelligence Intent and Guidance Crosswalk31

Intelligence Intent and Guidance Benefits

The concepts and direction contained in the intelligence intent and guidance benefits execution of mission command for the intelligence cell during large-scale combat operations in two primary ways. First, the commander’s intent and the intelligence intent and guidance allow the intelligence cell to immediately begin detailed planning and movement, which saves critical time during high-tempo operations. Second, the shared understanding gained from the intelligence intent and guidance primes the senior intelligence officer and intelligence cell members to be on the lookout for critical indicators that better predict enemy activity.28

A deep, shared understanding of the anticipated indicators increases the likelihood of detecting “exceptional information.”29 Exceptional information signals that a previously unconsidered opportunity or calamity may be underway that requires action. Exceptional information starkly contrasts with the expected indicators associated with the anticipated situation.30 For example, suppose we expect an enemy armored thrust along a particular avenue of approach to our front and then receive reports of tanks in our rear area. If this occurs, we need to recognize that we may be in an exceptional situation! While this example appears obvious, exceptional information can appear like background noise in an environment flooded with data if the senior intelligence officer and intelligence cell do not understand what should happen according to the commander’s visualization.

The senior intelligence officer issues their intelligence intent and guidance soon after receiving the commander’s intent and guidance. The delivery of the intelligence intent and guidance does not mean the senior intelligence officer stops thinking about the 10 big picture questions. The senior intelligence officer and intelligence cell must continuously assess and reframe enemy activity and conditions within the operational environment as a situation unfolds.32

You may ask: How is the senior intelligence officer supposed to craft their intelligence intent and guidance before conducting intelligence preparation of the operational environment? In the same way the commander writes their intent before the military decision-making process. The commander leverages anything and everything to craft their intent to include higher headquarters products, running estimates, and available expertise.33 The senior intelligence officer must do the same.

Conclusion

The intelligence intent and guidance is how the senior intelligence officer uniquely contributes value to the intelligence process. Fully embracing the mission command philosophy means conveying the commander’s intent and having the confidence and competence as the unit’s “chief of the intelligence warfighting function” to refine that intent further.34 Mission command was built for war, and one can only truly exercise the philosophy during war or in realistic, war-like training conditions.35 Competence is critical in these demanding environments.

Watch for part two “A Mission Command Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition,” to publish soon! It discusses the development of competence and intuition.

Endnotes

1. Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 1 October 2022), 1-4, 3-2.

2. Department of the Army, Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-0, Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 2-13; and Department of the Army, ADP 2-0, Intelligence (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 3-1.

3. Recent seminars and conversations influenced my thinking for this article. A presentation by LTG Milford Beagle influenced me to reflect on the unique role of the senior intelligence officer in large-scale combat operations. I am paraphrasing, but he recommends that all leaders reflect on and do those tasks only they can accomplish because of their unique organizational position. Separately, discussions during a seminar led by LTC Mark Kelliher influenced my thinking on mission command and its relationship to large-scale combat operations. I also benefited from presentations by COL Blue Huber, retired COL Matt Gill, and retired MG Robert Walters on the need to master intelligence fundamentals to meet the challenges of large-scale combat operations. COL Huber discussed the need for sensemaking in large-scale combat operations (not just sensing), the need for senior intelligence officers to provide compelling narratives (technology will not do this for us), and the need for the senior intelligence officer to support the commander’s activities during the operations process. Any errors are mine.

4. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, 2-13.

5. Department of the Army, ADP 5-0, The Operations Process (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 1-5.

6. Department of the Army, FM 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 16 May 2022), 2-10.

7. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 119.

8. Department of the Army, FM 3-0, Operations, 1-4–1-5.

12. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, 2-6.

13. Ibid., 2-14. Graphic adapted from original.

14. Department of the Army, FM 3-0, Operations, 8-2.

16. Ibid., 1-7; and Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, vii, 1-3–1-4, 1-9. The principles of mission command are competence, mutual trust, shared understanding, commander’s intent, mission orders, disciplined initiative, and risk acceptance.

17. Department of the Army, ADP 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 1-1, 5-2. Change 1 was issued on 25 November 2019.

18. Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 18 June 2022), GL-8.

19. Department of the Army, ADP 5-0, The Operations Process, 1-9.

21. Ibid., 2-11 (emphasis added).

22. Department of the Army, FM 3-0, Operations, 8-6.

23. According to a handout from the Command and General Staff School’s 2015–2016 Intermediate Level Education, the “questions the friendly should ask the enemy” are: “How can we predict an enemy action? How can we preempt an enemy action?” and “How can we prevent an enemy action?” These are good questions to consider.

24. Department of the Army, FM 5-0, Planning and Orders Production (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 16 May 2022), 1-5. Change 1 was issued on 4 May 2022. The mission variables are represented by the mnemonic METT-TC (I), which stands for mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available, time available, civil considerations, and informational considerations. FM 5-0 provides more details about the mission variables and informational considerations.

25. Department of the Army, Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 2-01.3, Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 1 March 2019), 5-1. Change 1 was issued on 6 January 2021. Besides branches and sequels, consider options the enemy may employ to improve their chances of success, including using specific capabilities such as nonlethal effects and chemical weapons.

26. Department of the Army, FM 2-0, Intelligence (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 1 October 2023), xiv. The term intelligence preparation of the operational environment replaces the term intelligence preparation of the battlefield.

27. The Command and General Staff School Intermediate Level Education handout previously cited in endnote no. 23 recommends, friendly forces should ask themselves, “Will the enemy action prevent me from accomplishing my task and purpose?” ADP 5-0, The Operations Process, provides a discussion outlining the need for commanders to modify guidance as the situation warrants.

28. Karl E. Weick, Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld, “Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking,” Organization Science 16, no. 4 (July–August 2005): 409-421, 411. The authors cite Klein et al., in press, for insights into how “mental models might be primed” by environmental cues or “a priori” permit noticing. Gary Klein, Jennifer K. Phillips, Erica L. Rall, and Deborah A. Peluso, “A Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking,” in Expertise Out of Context: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making, ed. Robert R. Hoffman (New York: Psychology Press, 2007).

29. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, 3-7.

31. Figure adapted from author’s original.

32. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, 3-17, 4-5.

33. Ibid., 2-5. Discusses intuitive decision making. Of course, commanders use analysis whenever possible based on the situation and available time. I also recommend ATP 5-01.1, The Army Design Methodology, for information on framing tools.

34. Department of the Army, FM 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, 2-10.

35. A senior intelligence officer is not practicing mission command in garrison when they choose not to micromanage their subordinates or when they allow a junior Soldier to brief the commander. Basic task delegation and stretch tasks are simply examples of good management practices. Mission command is a philosophy for war.

Author

LTC Matthew Fontaine is the G-2 for the 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, KS. He previously served as the G-2 for the U.S. Army Joint Modernization Command. He has deployed twice to Iraq and twice to Afghanistan, serving as an executive officer, platoon leader, battalion S-2, military intelligence company commander, and analysis and control element chief. He holds two master of military art and science degrees, one in general studies and the other in operational art and science, from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.