A Mission Command Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition

By LTC Matthew Fontaine

Article published on: February 20, 2024 in the Military Intelligence January–June 2024 Issue

Read Time: < 42 mins

Col. Nick Ducich, center, commander of the Cal Guard's 79th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, is briefed by his staff at Camp McGregor, New Mexico, on Jan. 31 during a Mission Rehearsal Exercise (MRX) in preparation for a deployment to Kosovo.

Introduction

Part one of this series discussed commanders driving the operations process using the mission command philosophy and their personal involvement in decision making. They furnish subordinates with their intent and planning guidance to provide purpose, direction, and motivation.1 This transitioned into a discussion of senior intelligence officers building upon commanders’ intent and guidance to develop their own intelligence intent and guidance. This is how senior intelligence officers uniquely contribute value to the intelligence process and fully embrace the mission command philosophy to convey topics such as the concept of intelligence for the operation, anticipated enemy options, and collection guidance. The senior intelligence officer must have the confidence and competence as the unit’s leader of the intelligence warfighting function to accomplish this warfighting function specific refinement of the commander’s intent and planning guidance.2

Sense Intuitively and Act Appropriately

Competence is the basis of mission command.3 The senior intelligence officer and the intelligence cell must be competent in fundamental intelligence tasks, which include the following:

- Provide intelligence support to force generation.

- Provide support to situational understanding.

- Conduct information collection.

- Provide intelligence support to targeting.4

The detailed planning and execution of these four tasks before and during large-scale combat operations are primarily the responsibility of the intelligence cell. This analytical work is the science of intelligence.

To sense indicators of enemy actions and act appropriately is the basis of the fundamental intelligence tasks. There are two aspects of sensing. First, is the observation of a threat signature by a sensor. A well-thought-out and executed collection plan makes this easier. Second, is recognizing the meaning of a threat signature. The senior intelligence officer and intelligence cell impart meaning to a threat signature by examining it within the context of the commander’s visualization of the situation. The senior intelligence officer acts appropriately by communicating this meaning in support of the decision-making process. These intuitive aspects of indicator sensing and communication are the art of intelligence. They are the unique contribution that the senior intelligence officer makes during execution of operations. To further understand the senior intelligence officer’s unique contribution to the success of the unit and commander during the execution of operations, we must examine the concepts of coup d’oeil and sensemaking mental models.

The Coup D’oeil Moment

One of the most remarkable qualities a military leader can possess is the uncanny ability to see or value what others cannot and to use that insight to seize an emerging opportunity or avert disaster. Military theorists refer to this quality by the French phrase, coup d’oeil. (Its exact translation being “blow/stroke of the eye.”)5 Prussian general and military theorist Carl Von Clausewitz discussed the term in his book On War in the chapter “On Military Genius,” describing the quality as “the quick recognition of a truth that the mind would ordinarily miss or would perceive only after long study and reflection.”6

Broadly, coup d’oeil is the “idea of a rapid and accurate decision” during any military operation.7 Author Malcolm Gladwell, in his book, Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking, notes, “brilliant generals are said to possess ‘coup d’oeil’,” which he defines as the “ability to immediately see and make sense of the battlefield” thanks to a leader’s “careful attention to the details of a very thin slice, even for no more than a second or two.”8

Another essential attribute of a coup d’oeil moment is criticality. The commander and senior intelligence officer make many adjustments throughout an operation, but few, if any, qualify as coup d’oeil moments. Coup d’oeil moments involve those unique battlefield appraisals made during crucial moments in the engagement that few leaders could make and even fewer could effectively operationalize. The decisions made, or not made, during these decisive periods can overwhelmingly influence the ultimate success or failure of the operation. As Clausewitz infers in his definition of coup d’oeil, these moments often pass us by. Subordinates admire those commanders who apply combat power precisely when needed to accomplish the mission in the din and confusion of war. We ask ourselves, how did they know to do that?

The Commander as Grandmaster

Competent commanders are like grandmaster chess players, which studies have shown “think differently than amateurs do.”9 Unlike amateur chess players who must examine their next move laboriously, grandmasters rapidly select their following best action based on “cues that are noticed on the board,” usually in as little as five seconds.10 A grandmaster’s expert intuition is possible thanks to the thousands of hours devoted to studying and playing chess, an example of the “10,000-hour rule” promoted by Gladwell in another of his works, Outliers: The Story of Success. The 10,000-hour rule posits that an individual must commit 10,000 hours of deliberate study and practice to master an activity. All experts in every vocation, including military leaders, develop expertise and intuition similarly.11 In the military, expert intuition is part of the art of command.

How does expertise increase the speed and accuracy of decisions? According to Nobel laureate Herbert Simon, many people would attribute an expert’s ability to respond quickly and effectively to a situation in their area as owing to “intuition” or “judgment.”12 This presents an unsatisfying answer. Instead, Simon imagines that if we peek inside the mind of an expert, “one would find that he had at his disposal repertoires of possible actions; that he had checklists of things to think about before he acted; and that he had mechanisms in his mind to evoke these, and bring these to his conscious attention when the situations for decisions arose.”13 Intuition, therefore, is a result of deep expertise.

The expert’s “checklist of things to watch out for” is built after long study and practice (the 10,000-hour rule).14 Mental models enable the expert to “recognize a very large number of specific relevant cues when they are present in any situation, and then to retrieve from memory information about what to do when those particular cues are noticed.”15

Intuitive decision making works best in stable, rule-based situations where we can get a lot of practice and immediate feedback on our actions. The game of chess is a perfect example. Intuition often falls short in complex situations with people and forces that adapt to changing conditions.16 In these situations, we are urged to rely more on “our rational brain” and “less on our subconscious gut.”17

Unfortunately, war may be the most complex and adaptive situation humans face. A commander or senior intelligence officer cannot count on having the time to engage in a lengthy, rational decision-making process in a high-tempo engagement. We must use our gut and our brains. Fortunately, even military members can acquire applicable mental models (checklists) for war by “learning how the world works” if we study “time-tested ideas.”18

What Are Mental Models?

Mental models are how we understand the world. Not only do they shape what we think and how we understand, but they shape the connections and opportunities that we see. Mental models are how we simplify complexity, why we consider some things more relevant than others, and how we reason. A mental model is simply a representation of how something works. We cannot keep all the details of the world in our brain, so we use models to simplify the complex into understandable and organizable chunks. Some of the most easily recognized mental models are maps, ecosystems, hierarchical organization, and feedback loops.19

The unique quality we are after in competent commanders is intuitive (and accurate) decision making in rapidly evolving situations, such as large-scale combat operations. It is that special quality—that spark of military genius—that a commander leverages in concert with accuracy-boosting, analytic decision-making processes (such as the military decision-making process, the Army design methodology, and the rapid decision and synchronization process) or with automated aids (such as artificial intelligence algorithms) whenever possible, but alone if the situation necessitates it.20 The unique contribution of the senior intelligence officer is to support the commander’s intuitive decision-making process in these situations.

The Aim of Intuition

What do commanders aim to intuit specifically? If we look to the definition of intent in doctrine, we see it necessitates transitions.21 “Successful commanders,” we are told, “anticipate future events by developing branches and sequels instead of focusing on details better handled by subordinates during current operations.”22 Fortunately, mission command enables the staff to “unburden higher commanders,” allowing them to focus on the “broader perspective…and critical issues” by empowering subordinates to act on the things they understand best due to their proximity to the issue.23 The critical issues the commander focuses on include specific transitions such as culmination and when and where to mass effects.

Benefits of Mission Command for the Senior Intelligence Officer

Mission command provides the same benefits for the senior intelligence officer that it does for the commander. The intelligence staff frees the senior intelligence officer to focus on delivering their unique contribution of understanding transition points and future operations (primarily from the perspective of the enemy commander) instead of focusing on oversight. Therefore, the relationship between the senior intelligence officer and the intelligence staff is reciprocal. The senior intelligence officer owes their subordinate staff their intelligence intent and guidance to provide purpose, direction, and motivation upon a mission’s receipt or anticipated receipt. The intelligence cell, operating with minimal oversight, owes the senior intelligence officer refined plans and intelligence that answers priority intelligence requirements. This allows the senior intelligence officer to use their mental energy to scan the environment for essential cues, act on them appropriately, and prepare future, broad view intelligence intent and guidance. The senior intelligence officer is primarily the “subconscious gut,” and the intelligence cell is the “rational brain.”

Embracing mission command will help the senior intelligence officer meet the first half of their primary role in large-scale combat operations—to provide the most complete intelligence picture available, even when tactically dispersed or in an environment of contested communication.

The Senior Intelligence Officer as Curator

The senior intelligence officer provides insights to the commander as an act of curation. Of the hundreds to thousands of reports and assessments flooding the intelligence cell in a large-scale combat operations environment, the senior intelligence officer must select those indicators or those assessments of enemy action or intent that mean more than others. Competent senior intelligence officers can detect and provide meaning to the hard to anticipate pieces of exceptional information because of their deep level of expertise. Or, in flashes of insight, they fuse a mass of previously unlinked reports or assessments to develop a single imperative requiring action. These insights represent the senior intelligence officer’s coup d’oeil-like moments and enable them to deliver timely intelligence to the commander, thus fulfilling the second half of their primary role in large-scale combat operations.24

I use the word “unique” when referring to the senior intelligence officer’s “unique contributions” to denote the special quality formal leadership positions provide for unifying effort among their subordinates. Others may be more intelligent, capable, and experienced, but within a unit, only one commander and one senior intelligence officer exist. Only the senior intelligence officer has the access and freedom (thanks to the intelligence cell) needed to develop immediate insights in some situations. Of course, the best senior intelligence officers realize insights can, and often do, come from another team member or emerge from a collaborative session. Sometimes, leaders have their most significant coup d’oeil-like moment or act of curation in the realization that a team member has recognized some profound truth and humbly acts on it! However, it is the senior intelligence officer that ultimately is responsible for enabling the commander’s visualization and understanding of the battlefield.

Sensemaking

Realizing a coup d’oeil moment personally, or setting the conditions for others to do so, is easier said than done. Understanding the concept of sensemaking is a significant first step to sensing intuitively and acting appropriately. Sensemaking is one of those time-tested ideas on how the world really works. Senior intelligence officers must build a mental model of the process.

The coup d’oeil quality is akin to the Army and the academic concept of sensemaking. The Center for Army Leadership describes sensemaking as the “deliberate, iterative effort to create understanding in complex situations.”25 Project Athena’s self-awareness assessments indicate how a leader “process[es] information for situational awareness” and “create[s] understanding in uncertain, novel, and ambiguous situations.”26 I emphasize the word “deliberate” in the Army description of sensemaking because this explanation casts sensemaking as a “slow,” analytical process rather than a “fast,” intuitive process like the one grandmaster chess players use when selecting their next move.27

Project Athena

What is Athena?

Athena is an Army leader development program designed to inform and motivate Soldiers to embrace personal and professional development. Adding to the Army’s culture of assessments, Athena uses sequences of assessments to increase Soldier self-awareness of leadership skills and behaviors, cognitive abilities, and personal traits and attributes. Assessment batteries complement the leadership skills developed at several Army schools. For each assessment completed, students receive a feedback report with their scores and information about how to interpret the scores.

Why is Athena Important?

Athena is all about self-awareness. By providing leaders with the tools to identify their strengths and recognize where to make improvements, as well as providing access to resources that support self-initiative and self-development, Army leaders can continuously learn new skills and improve their abilities.

Athena provides students an opportunity to expand their self-awareness and tailor self-development to their individual needs.28

Intuitive Sensemaking

Authors Karl Weick, Kathleen Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld take a different view of sensemaking. They see sensemaking as an intuitive but iterative process that unfolds in ambiguous situations, where “meanings materialize” rather than firmly develop after a linear analytic process.29 Sensemaking “involves turning circumstances into a situation that is comprehended explicitly in words and that serves as a springboard to action.”30 The authors identify eight facets to “the nature of organized sensemaking.”31 They are:

- Sensemaking organizes flux.32

- Sensemaking starts with noticing and bracketing.33

- Sensemaking is about labeling.34

- Sensemaking is retrospective.35

- Sensemaking is about presumption.36

- Sensemaking is social and systemic.37

- Sensemaking is about action.38

- Sensemaking is about organizing through communication.39

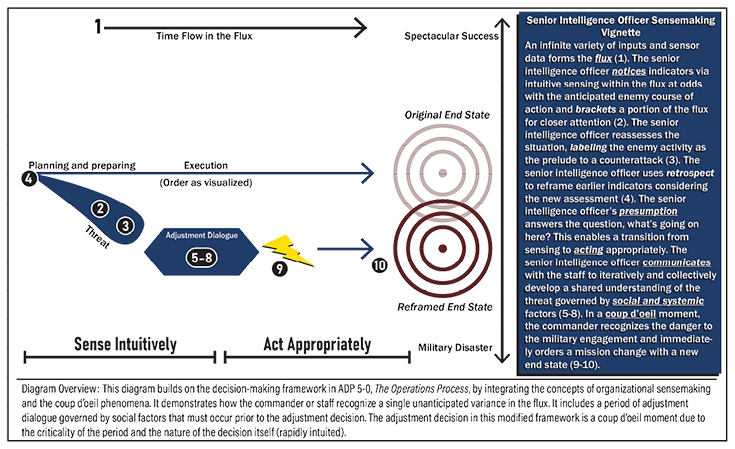

An examination of these facets will illuminate how a coup d’oeil moment can occur during high-tempo operations. Before delving into the sensemaking model, I will first provide an example of the sensemaking process. In the following fictional (and oversimplified) vignette, a senior intelligence officer describes the actions they take in a dynamic engagement when the situation begins to deviate from the expected enemy course of action.

Now, we will examine the vignette below employing Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld’s eight sensemaking facets. This will impart a better understanding of how this coup d’oeil moment occurred in part because of the senior intelligence officer’s unique contributions.

Sensemaking Vignette

I [the senior intelligence officer] left with the Tactical Action Center (TAC) at 0200. In the previous six hours, many reports indicated that the enemy had established a weak defense and significantly increased activity within its support zone. My intelligence cell and I struggled to keep pace with the volume of tactical reports. Sometimes all we could say with certainty was that the enemy was to our front. The enemy kept their critical systems dispersed and moving, and it was difficult to determine what the indicators meant in all this activity. Nevertheless, I assessed that the enemy was preparing to withdraw to more defensible positions to their rear and would likely conduct a withdrawal under pressure once attacked. The commander saw an opportunity and ordered an attack after a short planning session.

Our reconnaissance forces contacted the enemy disruption zone elements shortly after initiating movement at 0400, achieving their initial objectives with little difficulty. The commander ordered the main attack force to conduct a passage of lines with the reconnaissance elements and to clear the remaining enemy in the sector. The attack seemed well in hand by 0900, and our command nodes in the rear initiated movement to displace forward. The few staff officers forward with the TAC entered a planning cycle to determine how best to build on our momentum while the commander traveled to the main command post. One hour later, I received my next combat update. The situation at 1000 had dramatically changed. Communication with the rear command posts and intelligence cell had been severed 15 minutes prior, likely the result of an enemy non-kinetic effect after troubleshooting resulted in no restoral of services.

The main attack force bogged down because of unexpectedly high enemy armor concentrations, but its commander believed they could resume operations shortly. Distressingly, rear elements reported possible enemy ground reconnaissance in their sector before losing communication [exceptional information]. Moreover, a friendly reconnaissance report indicated significant enemy activity in the enemy support zone but provided no direction of travel. I went to the current operations officer and said I was increasingly concerned about the attack because of the enemy armor, loss of communication, and reconnaissance activity. I recommended directing our intelligence collection assets to confirm enemy activity in the support zone. The current operations officer replied, “Let’s see how this develops first.” Thirty minutes later, the main attack force reported receiving sustained indirect fire and a determined enemy defense.

I went to the frenzied operations officer and relayed the same information I told to the current operations officer. He said, “We will talk about it after we regain communications with higher. Besides, we can commit the reserve to get the attack moving again, if necessary.” I became increasingly concerned that the enemy defense was the start of a significant, unanticipated counterattack. Still, given the indicators I observed, I could not immediately oblige the operations team to act.

Frustrated, I talked to the Sergeant Major and told him my concerns. The commander returned to the TAC for a situation update moments later. The Sergeant Major said, “The deuce is worried we’re seeing an enemy counterattack, and I don’t like the situation either.” I described the key indicators and what they meant. The commander executed the rapid decision and synchronization process and, moments later, directed a transition to the defense. The commander ordered the reserve to enable the withdrawal of the main attack force to defensive positions along the original line of departure. The commander’s quick recognition of the friendly and enemy realities on the battlefield defeated the enemy counterattack. A coup d’oeil moment for sure.40

Organizes Flux. According to the authors, “sensemaking starts with chaos.”41 The senior intelligence officer in our example is “surrounded by an almost infinite stream of events and inputs” that form a “raw flow of activity from which she [they] may or may not extract certain cues for closer examination.”42 The inputs go beyond the fire hose of data from modern sensors and situation reports to include all the moments surrounding the “critical noticing.” of an indicator.43 The authors call the unending “raw flow of activity” the “flux.”44

The senior intelligence officer’s critical noticing of indicators of the counterattack occurred during a period where they received little sleep, conducted a final huddle with the intelligence cell, missed the morning meal, read reports, completed a tactical movement, and conducted planning. This activity forms just part of the flux that competes for the senior intelligence officer’s mental bandwidth and reduces the likelihood that the senior intelligence officer will intuitively sense indicators and act on them appropriately.45

Clausewitz captures the idea of flux in his description of coup d’oeil (see page 1)—coup d’oeil moments are rare because they require the recognition of some truth that usually is only uncovered retrospectively after “long study and reflection.” The commander’s and the senior intelligence officer’s challenge is to improve their chances of experiencing an intuitive coup d’oeil flash of insight during an engagement instead of reaching the awareness long after the battle.

Starts with Noticing and Bracketing. During the engagement, the senior intelligence officer noticed indicators within the flux at odds with the anticipated enemy course of action (COA). In response to this dissonance, the senior intelligence officer “orients” to these specific indicators and “notices and brackets possible signs of trouble for closer attention.”46

Mirroring Simon’s observations on expertise, the senior intelligence officer’s noticing and bracketing, according to Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, is made possible by “mental models” that are “primed” by environmental cues or “‘a priori’ permit” that allows them to “notice and make sense” of critical changes within the operational environment.47 The senior intelligence officer must “forcibly carve” an acute observation “out of the undifferentiated flux of raw experience” and label what it means; for example, a counterattack.48 We are asked to “notice that once bracketing occurs, the world is simplified,” like a blurry image that suddenly snaps into focus, revealing the subject.49

A Priori

A priori is a Latin term that means “from what is earlier.” A priori knowledge is knowledge that comes from the power of reasoning based on self-evident truths. The term usually describes lines of reasoning or arguments that proceed from the general to the particular, or from causes to effects.50

Competence is critical for a senior intelligence officer to forcibly carve and bracket potential cues in a complex environment. The senior intelligence officer must have mastery of doctrine, tactics, friendly and enemy COAs, and other mental models to be primed for sensemaking during execution. The commander must not only master these same things, but also command the unit. The senior intelligence officer, as co-driver of the intelligence process, reduces the commander’s cognitive burden as they drive both the intelligence and operations processes.

The senior intelligence officer’s expert understanding of the sensemaking mental model can further prime them to sense intuitively (notice) and act appropriately during large-scale combat operations. Think of sensemaking as the senior intelligence officer’s cognitive operating system whose applications are other mental models like doctrine and the anticipated COAs. Increase the number of applications and the operating system becomes more powerful; have a faulty operating system, or one without any features, and the software has no utility.

The nature of large-scale combat operations presents challenges for noticing the right indicators that will test even the most experienced sense-maker. First, a senior intelligence officer cannot always expect support from higher echelon’s information collection assets because large-scale combat operations may require tasking assets elsewhere. Second, a senior intelligence officer may not get information and intelligence collection reports fast enough (or at all) because of disrupted, disconnected, intermittent, and low-bandwidth effects. Then upon receipt of reports, the senior intelligence officer may not be able to make sense of them in time to influence the battle. Third, the enemy may execute deception activities that obfuscate their actual actions. Fourth, predicting indicators presumes a rational opponent who deploys their forces according to their doctrine; this may not always be the case. And finally, our own biases get in the way. We look for the indicators and warnings of threat activity that fit our preconceived notion of how the battle will unfold and ignore those that do not. Human factors are crucial in decision making, but often we do not appreciate them when developing the information collection plan.51

The senior intelligence officer must be physically or virtually present to scan the engagement and notice cues. An isolated senior intelligence officer (thanks to some non-kinetic effect in a rear command post) is useless in high-tempo combat operations. A forward senior intelligence officer can directly observe the situation and collaboratively make sense with the commander and other key personnel. A senior intelligence officer cannot expect an intelligence brief presented as part of a battle rhythm event at the main command post to meet all information requirements during large-scale combat operations.

Being forward provides another benefit in a disrupted, disconnected, intermittent, and low-bandwidth environment. Communication between the forward command post and the forces in contact may still be possible even if a non-kinetic event prevents communication with the rear, ensuring the senior intelligence officer can access the volume of tactical information at the combat edge. The senior intelligence officer’s unique role is to be centerstage during large-scale combat operations, sensing intuitively and acting appropriately.

Is About Labeling. Sensemaking requires “labeling and categorizing to stabilize the streaming of experience.”52 Labeling transforms what was seeming chaos into a form more useful for “plausible acts of managing, coordinating, and distributing.”53 In the medical field, a doctor provides a diagnosis to “suggest a plausible treatment.”54 In military intelligence, the senior intelligence officer’s role is assessing enemy activity (diagnosis) to anticipate the enemy COA and then spur the commander to develop a plausible reaction (treatment in medical terminology).

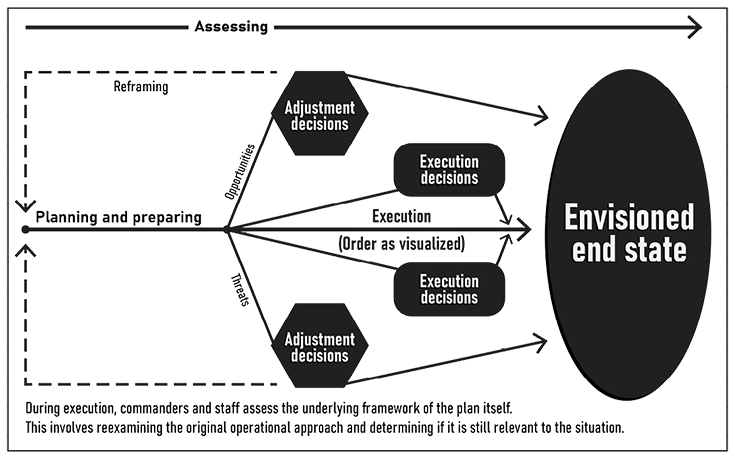

In doctrine, plausible reactions are the “adjustment decisions” a commander executes to move the operation toward the desired end state when what was thought to happen does not occur.55 The unit overcomes minor variances with fragmentary orders or execution of planned branches or sequels when a variance anticipated during planning occurs. Unanticipated significant variances may require reframing the problem or changing the mission to seize an opportunity or face a threat.56 In the vignette, the commander and staff never anticipated the possibility of a powerful enemy counterattack in their area of operations.

ADP 5-0, The Operations Process, provides an excellent framework illustrating the essentials of the decision-making process in the face of variance and unanticipated situations. (See Figure 1.) However, doctrine does not satisfyingly describe how the commander or staff recognize variances in the flux and communicate during adjustment dialogue to enable rapid organizational understanding of an emerging situation before acting. The coup d’oeil and sensemaking concepts get us closer.

Is Retrospective. Sensemaking is an act of hindsight (retrospect), providing understanding of what is happening now.58 The senior intelligence officer formulated the 1000 assessment after mentally reviewing and reframing the meaning of observed enemy activity to that point. The senior intelligence officer now recasts the morning’s light enemy activity as a tactic to lure friendly forces into an engagement area. They view reports of frenzied enemy activity in the support zone not as enabling a withdrawal, but as the transition to the offense. The key concept here is to realize what is happening now is already “at an advanced stage: the label follows after and names a completed act,” hopefully with enough time to make the necessary adjustment decisions.59

Figure 1. Decision Making during Execution57.

Is About Presumption. Sensemaking leads to formulating a “hunch” presumed to be correct within the individual’s mind.60 The senior intelligence officer first noticed a list of indicators at odds with the predicted COA. The senior intelligence officer believes an enemy counterattack is underway and recommends changes to the collection plan to test this hunch. “To test a hunch is to presume the character of the illness [in medical terms] and to update that presumptive understanding through progressive approximations.”61 In this way, sensemaking often appears to be the result of human “error-ridden activity” that requires continuous assessment and adjustment to the situation at hand—“the now of mistakes collides with the then of acting with uncertain knowledge.”62

Is Social and Systemic. Social factors influence sensemaking.63 In our example, the social factors influencing the senior intelligence officer may include previous interactions with the intelligence staff, the commander’s thoughts on the mission command philosophy—some commanders encourage staff input to their decision-making process while others are less inclined to do so—or prior negative feedback from the operations officer about the intelligence cell’s reporting.

Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld also encourage us to consider how social factors influence organizational sensemaking. The senior intelligence officer and others’ realization of the counterattack “unfolds” at different rates and depths partly due to social factors.64 We see this in the operations officer’s reluctance and the Sergeant Major’s readiness to change their read of the situation. Military leaders must consider how social factors within their organizations could positively or negatively influence sensemaking to improve decision making in high-tempo operations.

Figure 2. Sensemaking and Coup D’Oeil Vignette70

Is About Action. Sensemaking involves asking two essential questions. The first question is, what is going on here? And the follow-up question is, what do I do next?65 The senior intelligence officer’s enemy counterattack assessment (hunch) is directly “intertwined” with their efforts to update the information collection plan and influence the commander to make an adjustment decision.66 Communication between the commander and staff “leads to a continual, iteratively developed, shared understanding” of the new assessment.67

Of course, presumption brings risk; the senior intelligence officer could be wrong. Even so, sensemaking drives the senior intelligence officer and command to act appropriately in the dynamic situation, as understood now.

Is About Organizing Through Communication. Communication is vital to sensemaking. We can view sensemaking as an “activity that talks events…into existence.”68 Iterative dialogue organizes thinking to develop shared understanding. Once the senior intelligence officer communicates their concerns and assesses the situation, events become tangible and distinct within the flux.69

Analytic and Intuitive Sensemaking

Sensemaking and coup d’oeil require both analytical and intuitive thinking supported by deep expertise to come about. The senior intelligence officer must first notice the indicators in the flux before they can apply analytic, retrospective thinking to merge the various indicators into a coherent narrative of what the enemy is doing now. It is the act of intuitive curation that allows a senior intelligence officer to impart critical importance to a single or series of events in dynamic environments and represents another unique contribution. (See Figure 2.)

- Sensemaking Drives the Commander’s Activities

- Sensemaking helps drive the commander’s understanding, visualizing, describing, directing, leading, and assessing activities during the operations process. The commander cannot—

- Understand without first noticing.

- Visualize without first bracketing.

- Describe without first labeling and retrospectively explaining how the current situation emerged.

- Direct without presumption or without an understanding of the social factors in their organization.

- Lead without acting through communication.

- Assess without asking, what is going on here?

A sensemaking senior intelligence officer adds value to every step of the operations process. We should build our sensemaking capability so we can sense intuitively and act appropriately during large-scale combat operations.

Build Sensemaking Capability

A good way to build sensemaking capability is to access the Project Athena Leader Self-Development assessments and other resources available through the Center for Army Leadership.71 Sensemaking is one of the leadership assessments available to the military cohorts. If a user identifies it as an “Area I Need to Improve In,” the site will suggest 32 academic, business, and doctrinal resources with descriptions of topics including other time-tested ideas such as complexity, systems thinking, and analysis. A senior intelligence officer can easily integrate the 32 resources into the intelligence cell’s training or individual development plans.

These tools are excellent for developing one’s theoretical understanding of sensemaking. However, we instinctively know that reading and viewing all 32 resources that Project Athena offers will neither turn an amateur chess player into an intuitive grandmaster nor an inexperienced senior intelligence officer into the Napoleon of intelligence officers. Players must play chess and study theory to improve. Likewise, senior intelligence officers require repetition in making sense of complex situations in war or war-like conditions to deliver complete and timely intelligence. How do we accomplish this? It is one thing to pull out a chess board, another to conduct war. Training, the study of doctrine, and real-world intelligence support are the obvious solutions, but what should a senior intelligence officer do to hone their coup d’oeil and sensemaking capacity outside these conditions to maximize their value?

Reading and Empathy Building

Here is a simple solution: read military memoirs. Ardant du Picq remarked: “The man is the first weapon in battle: let us then study the soldier in battle, for it is he who brings reality to it. Only the study of the past can give us a sense of reality and show us how the soldier will fight in the future.”72 Archibald Wavell builds on this idea, urging audience members in a 1939 lecture at Trinity College, Cambridge, to “read biographies, memoirs, and historical novels” to “get at the flesh and blood of it, not the skeleton.”73 He ascribed Napoleon’s victory in 1796 to his “profound knowledge of human nature in war,” not Napoleon’s “maneuver on interior lines or some such phrase” of “little value.”74

Wavell’s comments underscore the importance of human and social factors and how they influence war’s outcomes. Senior intelligence officers should take heed and develop mental models of human behavior in stressful conditions, like war, to the same extent we build our understanding of purely military matters, like threat tactics. Recent studies by the University of Toronto have lent a scientific basis to Wavell’s recommendation: “any good story—whether fiction or nonfiction…will likely boost empathy.”75 Keith Oatley, professor emeritus of cognitive psychology, wrote, “fiction might be the mind’s flight simulator.”76 For the military professional, military narratives are our war simulator.

Why is empathy important? According to Zachary Shore, “strategic empathy” enables people to “think like their opponents,” to envisage their future actions.77 Empathy allows the senior intelligence officer to “pinpoint what truly drives and constrains the other side” and leverage these insights to notice and bracket the “information that matters most” in the flux (curate) or, in Gladwell’s language, identify the correct “thin slice.”78

How do you know when to stop everything and ask yourself, what is going on here? Shore provides an answer. He advises zeroing in on an opponent’s behavior when they significantly diverge from what you expect them to do. He calls these moments “pattern breaks” and “meaningful ones” (think exceptional information) reveal “what he [the opponent] values most.”79

Memoirs provide an empathetic senior intelligence officer the mental “sets and reps” outside large-scale combat operations to understand how the conditions of war and the unique situation at hand may influence analytic and intuitive decision making and sensemaking for both friendly and enemy forces.80

One thing about future warfare seems certain: a senseless senior intelligence officer is guaranteed not to add value in large-scale combat operations. Senior intelligence officers must do everything possible to build their repertoire of mental models to understand anticipated behavior and rapidly spot meaningful changes in the environment. Understanding human nature in war is a great start.

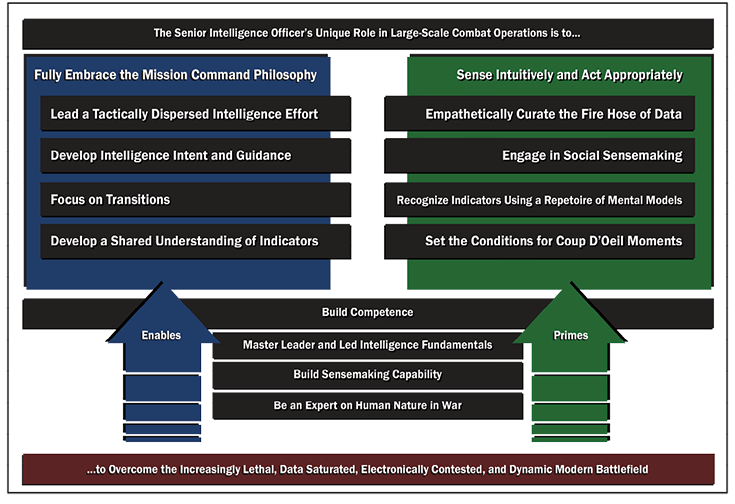

Figure 3. The Senior Intelligence Officer’s Unique Role in Large-Scale Combat Operations81

Conclusion

The senior intelligence officer contributes unique value to the commander and intelligence cell on the tactically dispersed and electronically contested modern battlefield during large-scale combat operations. (See Figure 3.) Fully embracing the mission command philosophy makes this possible. The senior intelligence officer intuitively frames how the future enemy operation is likely to unfold in the form of the intelligence intent and guidance. This conceptual guidance better enables the intelligence cell to form detailed plans and execute operations while tactically dispersed or in a disrupted, disconnected, intermittent, and low-bandwidth environment. The senior intelligence officer’s future orientation combined with the intelligence cell’s detailed analysis results in more accurate, complete, and timely intelligence.

The detailed work of the intelligence cell frees the senior intelligence officer to focus on the “big picture” and scan the environment for indicators during execution. The senior intelligence officer is a unique, empathetic curator of the fire hose of data and input that forms the flux of large-scale combat operations, thanks to their position and access on the battlefield. Because they understand the human nature of decision making in war (and in general), the senior intelligence officer has an uncanny ability to detect, label, and ascribe meaning to hard-to-recognize essential information in rapidly changing situations. These timely insights spur the commander’s understanding, visualizing, describing, directing, leading, and assessing activities and can lead to a coup d’oeil, “Aha!” moment during decisive periods.

Competence primes the senior intelligence officer to recognize indicators and essential information. A wide-ranging repertoire of mental models constructed during personal preparation of the battlefield and after a deep study of the operational environment makes a senior intelligence officer’s expert sensemaking possible. Valuable intelligence officers recognize that people fight wars and develop an empathetic mindset through reading and experience to sense their opponent’s next move during high-tempo operations.

The senior intelligence officer is a leader in large-scale combat operations, providing purpose, direction, and motivation to the intelligence cell in the most challenging and demanding conditions. The intelligence cell appreciates quality management in garrison but needs mission command in war. Competence is the mission command philosophy’s cost of entry. We must relentlessly develop competence in ourselves and our teams to provide value in large-scale combat operations.

Final Thoughts

This article is more meditation than a fully completed imperative. It remains unclear precisely what future wars will hold for the intelligence warfighting function or how to “forcibly carve” out a vital indicator in the tangled mass of inputs during large-scale combat operations. Detailed planning and analysis will assist the senior intelligence officer’s ability to sense and act tremendously, and technology will increasingly do so, but expert intuition will always be crucial to military success.

Preparation will be essential to add value in large-scale combat operations, so studying concepts like sensemaking and the senior intelligence officer’s unique role in mission command is worth more than a thought. And it will not hurt to widely read military narratives to develop your empathetic mindset. Do everything possible to develop your repertoire of mental models on “time-tested” topics related to human nature in war.

Endnotes

1. Department of the Army, Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 31 July 2019), 1-1, 5-2. Change 1 was issued on 25 November 2019.

2. Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 16 May 2022), 2-10.

3. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 1-7.

4. Department of the Army, FM 2-0, Intelligence (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 01 October 2023), 1-7–1-8.

6. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 102.

8. Malcolm Gladwell, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (New York: Little, Brown, 2005), 44 (emphasis added).

10. Franzen, “Brain Study”; and Daniel Kahneman and Herbert Simon, “Daniel Kahneman and Herbert Simon on Intuition,” Psychology, Farnam Street Blog, 2023, https://fs.blog/daniel-kahneman-on-intuition/. The quote is attributed to Herbert Simon.

12. Kahneman and Simon, “Intuition.” The quote is attributed to Herbert Simon.

13. Ibid. The quote is attributed to Herbert Simon.

14. Ibid. The quote is attributed to Herbert Simon.

15. Ibid. The quote is attributed to Herbert Simon.

18. Ibid.; “Mental Models: The Best Way to Make Intelligent Decisions (~100 Models Explained),” Farnam Street Blog, 2023, https://fs.blog/mental-models/#military_and_war; and Clausewitz, On War, 146-147. Clausewitz argues that a commander must “carry the whole intellectual apparatus of knowledge with him” and “always be ready to bring forth the appropriate decision,” phrases we could update using today’s language to “a commander must master mental models to enable rapid, intuitive decision making.” He also states a commander must be an “acute observer of mankind,” a topic this article also discusses further on.

20. Clausewitz, On War, 102. I refer here to Clausewitz’s concept of coup d’oeil, which he states is a necessary component of military genius; Rileywrites87, “The Meaning of Critical Analysis in ‘OnWar’,” Thinking with Clauswitz, 31 January 2015, https://onclausewitz.blogspot.com/. The author directly equates Clausewitz’s idea of military genius with a commander’s “intuitive judgement.”; Matthew Fontaine, “On the Outside, Looking In: Three Simple, Accessible Tools to Enhance Your Assessment,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin, no. 3 (July–December 2022): 73, https://mipb.army.mil/articles/2022-jul-dec/fontaine-on-the-outside. See the discussion on the errors associated with expert forecasts and ways to improve your assessments. A key difference is that my writing focuses on the accuracy of predictions, where the expert has time to do an in-depth analysis to support a prediction. As stated in the article, no one in war can count on having the time to apply accuracy-boosting decision aids. Still, even “simple mechanical rules” are “generally superior to human judgement,” according to a study by Paul Meehl referenced in Daniel Kahneman, Oliver Sibony, and Cass R Sunstein, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2021), 114. The bottom line is that commanders and senior intelligence officers should make significant efforts to leverage structured decision-making processes or software whenever possible to improve the accuracy of their predictions, even in high-tempo operations. They also need to go to war prepared, with a repertoire of mental models (doctrine, theories on human behavior, and historical examples) already in their minds.

21. Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 18 June 2022), GL-8.

22. Department of the Army, ADP 6-0, Mission Command, 1-4.

24. Previous reading and professional military education influenced my thoughts on curation (to include the word itself) within complex situations. However, I am unable to cite a specific author now. The interested reader can find much information on curation, particularly data curation. Data curation will undoubtedly influence future intelligence activities, and senior intelligence officers will have to leverage these tools. Separately, author Zachary Shore notes the need for identifying the correct information to examine in the “ocean of information,” which undoubtedly influenced my thinking here. However, he does not use the word curation (here anyway). See Excerpts and Reviews of A Sense of the Enemy: The High-Stakes History of Reading Your Rival’s Mind by Zachary Shore, https://www.zacharyshore.com/a-sense-of-the-enemy.html.

25. Marilyn Willis-Grider, “Project Athena AEAS Assessment Status,” Center for Army Leadership, last modified 22 May 2023, 14:57:56, https://www.capl.army.mil/Athena/athena-articles/Athena-Assessments.php emphasis added). [Link is no longer accessible]

27. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

28. Department of the Army, “Athena,” Center for Army Leadership, last modified 22 May 2023, 14:57:56, https://www.capl.army.mil/Athena/ [Link is no longer accessible].

29. Karl E. Weick, Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld, “Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking,” Organization Science 16, no. 4 (July–August 2005): 409-413; and Jean Helms-Mills, Making Sense of Organization Change (London: Routledge, 2003).

30. Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking,” 409.

40. Ibid., 409-413. I modified the authors’ nursing example to craft this vignette.

45. Ibid. I modified the authors’ nursing example for the material in this paragraph.

47. Ibid. The authors cite Klein et al., in press, for insights into how “mental models might be primed” by environmental cues or “a priori” permit noticing. Gary Klein, Jennifer K. Phillips, Erica L. Rall, and Deborah A. Peluso, “A Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking,” in Expertise Out of Context: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making, ed. Robert R. Hoffman (New York: Psychology Press, 2007).

48. Ibid., (emphasis added). The authors cite R. Chia for the quote, “forcibly carve out of the undifferentiated flux of raw experience.” Robert Chia, “Discourse Analysis as Organizational Analysis,” Organization 7, no. 3 (August 2000): 513.

49. Ibid. The quote belongs to the authors; the analogy is mine.

51. I want to acknowledge Mr. Tamotsu (Tee) Iwaishi for his thoughts and assistance improving this paragraph. Mr. Iwaishi noted deception and biases as challenges that interfere with our ability to recognize indicators and warnings.

52. Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking,” 411.

55. Department of the Army, ADP 5-0, The Operations Process (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 4-6–4-7.

57. Ibid., 4-6. Figure adapted from original.

58. Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking,” 411-412.

62. Ibid., 412; and Marianne A. Paget, The Unity of Mistakes (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988).

63. Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking,” 412.

68. Ibid., 413 (emphasis added).

69. Ibid., 411-412; James R. Taylor and Elizabeth J. Van Every, The Emergent Organization: Communication as Its Site and Surface (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2000). The authors attribute insights on iteration and shared understanding to J.R. Taylor and E.J. Van Every, 2000; and Robert Chia, “Discourse Analysis as Organizational Analysis,” Organization 7, no. 3 (August 2000): 517. The authors attribute insights on a labeled topic becoming tangible and distinct in the flux to R. Chai, 2000.

70. Figure adapted from author’s original. The diagram is an amalgamation of Figure 4-2 from ADP 5-0, The Operations Process, combined with insights from Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking,” Carl von Clausewitz, On War, and Malcolm Gladwell, Blink.

71. See “Athena Leader Self-Development Tool,” Center for Army Leadership, https://capl.army.mil/Athena/sd-tool/#/. [Link is no longer accessible]

72. Archibald Wavell, Generals and Generalship (New York: Macmillan, 1941), 24. Quote attributed to Ardant du Picq.

73. Archibald Wavell, Generals and Generalship, 25.

74. Ibid. Now there is a need to study doctrine and tactics! These military models are helpful for the senior intelligence officer, as they provide a starting point for what a rational opponent may do. However, General Wavell also implies that other factors, such as leadership and morale, influence victory in war.

77. Zachary Shore, A Sense of the Enemy: The High-Stakes History of Reading Your Rival’s Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) 2, quoted in Matthew Fontaine, “Understanding a Complex World: Why an Emphasis on Empathy Could Better Enable Army Leaders to Win” (master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2016), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1019977.pdf. See my thesis for a more in-depth argument on the importance of empathy to military personnel.

78. Zachary Shore, Excerpt of A Sense of the Enemy: The High-Stakes History of Reading Your Rival’s Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), https://www.zacharyshore.com/a-sense-of-the-enemy.html. Zachary Shore also alludes to the power of curation and cites Gladwell’s “thin slice” in this summary. I discuss Zachary Shore’s (and other’s) models and insights more in my thesis. (See endnote no. 64.)

79. Zachary Shore, Sense of the Enemy, 6-8. I also discuss Shore’s pattern breaks in my thesis. (See endnote no. 64.)

80. Clausewitz, On War, 102. Also, see Clausewitz’s chapters on “critical analysis” and “on historical example” for a more sophisticated discussion of how to hone your military mind by analyzing military decision makers in historical situations; and Rileywrites87, “Thinking with Clausewitz.” Rileywrites87 states that Clausewitz’s theory aimed to advance the “commander’s intuitive decision-making abilities” using “critical analysis” to gain experience outside war vicariously.

81. Figure adapted from author’s original, which was created from insights cited throughout the article.

Author

LTC Matthew Fontaine is the G-2 for the 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, KS. He previously served as the G-2 for the U.S. Army Joint Modernization Command. He has deployed twice to Iraq and twice to Afghanistan, serving as an executive officer, platoon leader, battalion S-2, military intelligence company commander, and analysis and control element chief. He holds two master of military art and science degrees, one in general studies and the other in operational art and science, from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.