Intelligence Cooperation and Individual Decision Making

Historical Lessons in Joint Intelligence Sharing

By Second Lieutenant Kyle J. Melles

Article published on: April 30, 2024 in the Military Intelligence January–June 2024 Issue

Read Time: < 16 mins

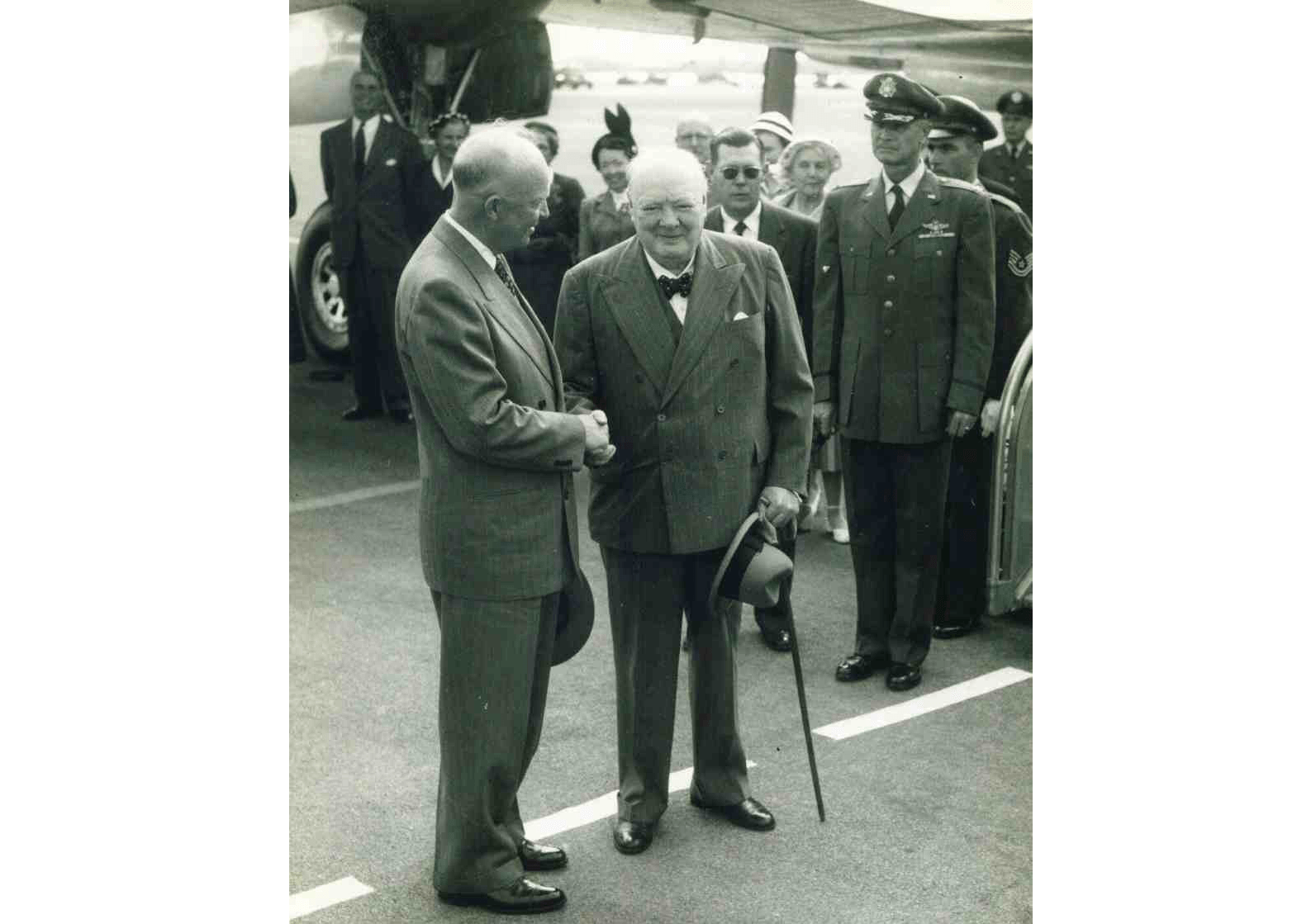

President Eisenhower bidding farewell to Prime Minister Churchill at the conclusion of the Bermuda Conference, December 1953. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Introduction

As the United States national security strategy shifts to focus on competition against other major powers, national intelligence leaders must build stronger relationships with their foreign military counterparts, increase individual and shared understanding of regulations and doctrine with our allies and partners, and implement mission command principles in decision making. Each of these priorities are the outcome of lessons learned in the early 1950s when inadequate intelligence sharing between the United States and the United Kingdom resulted in significant consequences for both global superpowers. While most studies of the special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom highlight the sustained success of their intelligence cooperation, they often underplay or completely ignore the setbacks experienced in the early 1950s. Other studies, such as Jake Harrington and Riley McCabe’s “The Case for Cooperation: The Future of the U.S.–UK Intelligence Alliance,” advocate for a more critical analysis of the relationship, while including recommendations for amending the relevant national strategies.1 The historical record holds many additional undiscussed lessons for intelligence cooperation, decision making, and interoperability.

U.S.-UK Special Relationship

The term special relationship refers to “the close political, cultural, and historic ties between the United Kingdom and the United States.”2 Winston Churchill was the first to use the term during a speech at Westminster College, Missouri, in 1946.3

November 1945, shows Harry Hinsley, Sir Edward Travis and John “Brig” Tiltman, all of whom were English intelligence officials instrumental in the initial UKUSA agreement of 5 March 1946. (Image courtesy of The National Archives, United Kingdom)

On 5 March 1946, following significant signals intelligence cooperation successes between the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II, the two nations signed the top secret British-U.S. Communication Intelligence Agreement, known as the UKUSA Agreement. The UKUSA Agreement committed both world powers to sharing signals intelligence and communications intelligence between their respective intelligence agencies.4 The Burns-Templer Agreements, made between 1948 and 1950, built on the UKUSA Agreement by promising the free exchange of intelligence and classified military information between the United States and the United Kingdom.5 These agreements greatly improved Western capabilities to confront the totalitarian Soviet Union during the Cold War. The Burns-Templer Agreements, however, experienced implementation difficulties at the practical level because of inconsistencies between the two nations’ visions of their intelligence sharing obligations.

Seven decades later, in 2021, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia signed a trilateral agreement, known as AUKUS.6 AUKUS focuses on collaboration in developing technology and information capabilities. This agreement is more aspirational in both geographical breadth and scope than its predecessor. However, the outcomes for its stakeholders remain consistent with the Burns-Templer Agreements by seeking to protect a contemporary world order against perceived emerging threats. To fulfill these lofty agreements for intelligence and defense cooperation, relationships are particularly essential. In the 2020 Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin article, “Building Intelligence Relationships,” LTC Casey Ramirez and MAJ Megan Spieles wrote, “Intelligence officers must establish relationships with other organizations across the intelligence community.”7 Both the importance and the complexity of establishing intelligence relationships is exacerbated when they exist between strategic allies. In the multipolar world of today, a new generation of agency officials must provide consistent and sound integration between the 18 U.S. intelligence community member organizations and our strategic partners.

Burns-Templer and Top-Down Strategic Shortcomings

The Burns-Templer Agreements were named after Assistant to the Secretary of Defense, Major General James H. Burns, and Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lieutenant General Sir Gerald Templer. These two men led the delegations of the United States and United Kingdom that produced the agreements.8 These 1950s agreements fell short of accomplishing their projected extensive intelligence cooperation due to the poor implementation by American officers in their engagement with British personnel. The agreements called for “a full and frank interchange to the greatest practicable degree of all classified military information and intelligence, except in a limited number of already declared fields.”9 In the context of the Cold War and threats from authoritarian regimes, including the Soviet Union in Europe and China on the Korean Peninsula, the agreements allowed for strong integration of the United States and the United Kingdom’s intelligence capabilities, particularly concerning signals intelligence.

The agreements left British intelligence personnel, like the Ministry of Defence’s Chiefs of Staff Committee Secretary, Robert W. Ewbank, feeling that there was a certain “one-sidedness” to the intelligence sharing efforts.10 While the national strategy and legal documents provided for open intelligence sharing, American and British intelligence professionals remained disconnected at the practical decision-making level. From 1950 to 1953, British officials integrated American officers into their intelligence departments, and the United Kingdom Joint Intelligence Committee often sent reports to the United States Joint Intelligence Committee. However, American officials repeatedly did not reciprocate.

The Korean War offers an operational example that reflects current United States and United Kingdom national strategies. The infamous Battle of the Imjin River, in 1951, illustrates the relationship divide and intelligence sharing challenges between the two allies during those years. When communist China invaded United States-backed South Korea through North Korea in June 1950, the United Nations requested support from its member nations. Britain agreed to send troops to repel the Chinese offensive. They included the 29th Independent Infantry Brigade Group. One of the brigade’s subordinate units was 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, known as the Glorious Glosters, led by Lieutenant Colonel James Carne.11 During the battle, from 22–25 April 1951, Chinese infantry surrounded and overpowered the Glosters. As the Chinese infantrymen closed in, Brigadier Tom Brodie of the 29th Infantry Brigade called his American superior, Major General Robert H. Soule, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, to convey the Glosters’ extremely tenuous position. He described their position as “a bit sticky.”12 Major General Soule interpreted this to mean that the Glosters were having a difficult time, but they did not need reinforcements or to withdraw, though Brigadier Brodie desperately needed assistance.13 This miscommunication led to the Glosters’ unnecessary standoff to defend South Korea’s capital, Seoul, from the Chinese infantry. When the Glosters withdrew, after holding off the Chinese for multiple days, the Chinese infantry had captured over 500 of the Glosters. The official historian of the war, General Sir Anthony Farrar-Hockley, who was a prisoner of war following the Battle of the Imjin, believed that the Glosters could have avoided this standoff, and their imminent capture, had the British and American leaders coordinated beforehand.14 This example illustrates the stakes that individual relationships hold in competition between major powers.

In addition to the lack of relationship building, many intelligence cooperation shortcomings between the United States and the United Kingdom stemmed from the personalities and decision making of individual officers. After multiple attempts to address their concerns with senior American intelligence officials, in 1951 and 1952, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence, Chiefs of Staff Committee wrote a brief for Prime Minister Winston Churchill on areas of concern to address with American President Dwight Eisenhower at the Bermuda conferences in 1953. The United Kingdom’s Chiefs of Staff Committee Secretary, Robert W. Ewbank, decided that the problem stemmed from the United States national regulations, which governed the interpretation of the Burns-Templer Agreements. These regulations allowed U.S. officers “unlimited scope to evade the provisions of the Burns-Templer Agreements.”15 Secretary Ewbank believed the main shortcomings of the United States and the United Kingdom’s intelligence cooperation included “the awkwardness of individual American officials, which is often due…to uncertainty about their own positions” and the equivalent positions of their British counterparts.16 Ewbank viewed the “inability of the Americans…to interpret their own security regulations in a helpful manner” as the biggest obstacle to intelligence cooperation.17 He wanted to persuade reluctant American agency officials that they would benefit from intelligence cooperation with the United Kingdom, though many American officials clearly recognized the importance of the special relationship in theory.

Roll call of survivors of the Gloucestershire Regiment (Glosters) after the Battle of Imjin River, 1951. Forty of the 750 man regiment managed to reach safety. (Image courtesy of the National Army Museum, United Kingdom)

Bermuda Conferences

During the 20th century, officials from the United States and the United Kingdom met on the island of Bermuda to discuss diplomatic issues. One of these meetings took place from 4–8 December 1953. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, French Premier Joseph Laniel, and French Foreign Minister George Bidault met to discuss issues relating to international security; an end to the Korean War was one of the topics discussed. The meeting did not result in the signing of any major agreements.18

In December 1953, Winston Churchill met with President Eisenhower in Bermuda. The two leaders discussed improvements to their military intelligence cooperation. Eisenhower and his Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Allan Dulles (younger brother of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles), responded positively to British concerns over intelligence cooperation, though other American intelligence officials held dissenting opinions.

Implications for Modern-Day Military Intelligence Personnel

Considering the parallels between the Burns-Templer Agreements and the AUKUS trilateral partnership introduced in 2021, as well as the return to competition between major powers as a national strategy focus, the historical context provides multiple lessons for intelligence leaders. It is essential that well-prepared military intelligence professionals at a joint command determine their corresponding position in the allied force and develop positive and professional relationships with them. They must also improve their understanding of relevant regulations and directives, and when in a command position, ensure their subordinates have those same opportunities. The commander’s intent must provide clear and direct guidance to implement proper intelligence dissemination and sharing, though the senior leader must make the final decisions.

Fostering Professional Relationships. Relationships are essential to intelligence cooperation efforts. Relationships between partner forces come with increased barriers. While the relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom has not always been harmonious, it presents greater opportunities for both sides when forces are well-integrated within their partner’s architecture. U.S. intelligence professionals must continue to learn and understand the positions of their allied counterparts. Fortunately, today’s intelligence professionals have clear guidance on the importance of fostering relationships outlined in joint doctrine with basic principles for multinational intelligence sharing.19 Yet, the implementation of these principles still varies based on individual decision making. Commanders can facilitate intelligence sharing and interoperability by incentivizing cross-cultural opportunities and training that familiarizes their subordinates with the norms and standards of partner forces. Had the United States military intelligence officers internalized these lessons following the Burns-Templer Agreements, there might have been greater architecture integration and fewer claims of one-sidedness from the United Kingdom’s Chiefs of Staff Committee.

Understanding of Regulations. Well-prepared U.S. military intelligence professionals must take personal responsibility to read and understand the relevant directives for their area of responsibility. As Secretary Ewbank outlined for Prime Minister Churchill in 1953, from the British perspective, intelligence cooperation with Americans was a convoluted affair that varied based on the individual officer’s perspective. The Burns-Templer Agreements clearly intended for expansive intelligence sharing between the two countries, within preset limits. And yet, U.S. national regulations allowed individuals to bypass the provisions of the agreements. An argument for greater synchronization between regulations and national strategy is beyond the scope of this article, but each individual must understand the directives of the Department of Defense and those of partner forces in a consistent manner to prevent the previous conflicts experienced by our strategic ally. The U.S. intelligence community clearly did not follow the intentions of the national strategy outlined in the UKUSA Agreement. The return to multipolar competition in the 21st century requires adherence to the national strategy by all individuals for intelligence cooperation to be effective.

Applying Mission Command. Military intelligence leaders must use the mission command principles to guide their decision-making process. Commanders share the responsibility for greater understanding of strategic goals and how they apply to intelligence cooperation. While intelligence leaders in the early 1950s did not have official mission command guidelines, today’s leaders have the principles of mission command to guide their intelligence sharing decisions. Two of those principles, mission orders and commander’s intent, carry especially important implications for implementation of joint intelligence. A lack of a clear commander’s intent contributed to the inconsistent actions of American officers conducting joint intelligence with British forces in the early 1950s. The commander’s intent gives subordinates knowledge of their purpose, key tasks, and conditions that define the desired end state.20 In cases where the national strategy allows for expansive sharing, with certain limitations, the commander’s intent should articulate how intelligence professionals will achieve the strategy guidelines at the practical level.

At the same time, the mission command principle of mission orders ties into the main shortcoming of the Burns-Templer Agreements: the individual decides how to accomplish the commander’s desired outcome. Mission orders are directives from the commander that “allow subordinates maximum freedom of action in accomplishing missions.”21 Secretary Ewbank cited the American officers’ lack of confidence in their own abilities and direction as a primary shortcoming in the two nations’ intelligence cooperation. While the commander’s intent, aligned with expansive intelligence cooperation, aids the officer, the final decision making will always come from the intelligence professional’s personal experience and decision-making abilities. The decisions of intelligence sharing are complicated by the critical thinking needed when determining intelligence dissemination. Joint intelligence between military allies comes with a paradox in that “it is only valuable when shared…but the more it is shared the more it risks being compromised.”22 This implication for intelligence professionals builds upon the other two implications in that while increased understanding of doctrine and directives and improved relationships can assist decision making, no amount of assistance will entirely remove the grey area of decision making confronted by an intelligence professional.

Conclusion

The lessons from the United States successful yet flawed special relationship with the United Kingdom and their cooperative response to authoritarian regimes in the 1950s can guide intelligence professionals toward sound decision making and mission readiness in the modern world. Our intelligence collection and cooperation have changed since the Korean War and the opening stages of the Cold War, but the dynamics of competition in a multipolar world remain similar. In today’s demanding environments, awareness and understanding of our partners’ and allies’ capabilities are exceedingly important. Today’s military decision makers must make informed judgements faster than the intelligence officials of the 1950s. Fortunately, today’s intelligence professionals also have more doctrine and other guidance to complement their decision making.

The special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom is still essential in the 21st century to confronting Russia’s revanchist operations and rising competition with China. Seventy years after the meeting between Prime Minister Churchill and President Eisenhower, similar threats continue to require seamless intelligence cooperation between the two Western strategic allies. As the United States and the United Kingdom’s national values and geopolitical interests continue to align, American military intelligence professionals will face difficult and uncertain decisions for cooperation and intelligence sharing with the United Kingdom.

Endnotes:

5. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1950, Volume 3, Western Europe, eds. David H. Stauffer, Charles S. Sampson, Lisle A. Rose, Joan Ellen Corbett, Frederick Aandahl, and John A. Bernbaum (Washington DC: Government Publishing Office [GPO], 1977), Document 702, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1950v03/d702. Memoranda, notes, and annexes compiled by Norwood W. Watts, Secretary of State–Defense Military Information Control Committee. The documents were for guiding and informing the Departments of State and Defense. These documents are the official record of the Burns-Templer Agreements.

8. Foreign Relations of the United States, Document 702.

13. Andrew Marr, A History of Modern Britain (London: Pan Macmillan, 2007).

14. Ezard, “Needless Battle.”

15. “Memorandum Number 294 of 1953.”

19. Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 2-0, Joint Intelligence (Washington DC: The Joint Staff, 26 May 2022), II-33.

20. Department of the Army, Army Doctrine Publication 6-0, Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 1-10.

Author

2LT Kyle Melles is a military intelligence officer stationed in England as a Fulbright Scholar. He is researching security legislation at Warwick University. He holds an undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. Louis, MO.