Consolidating Gains in Detainee and Interrogation Operations

Promoting Cooperative Training Between Military Intelligence and Military Police

By Chief Warrant Officer 3 Kyle Clark

Article published on: May 6, 2024 in the Military Intelligence January–June 2024 Issue

Read Time: < 16 mins

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21236/AD1307194

Introduction

“Failure to consolidate gains generally leads to failure in achieving the desired end state,” and “conducting detainee operations plays a significant role in consolidating gains.”1 With these two statements, FM 3-0, Operations, emphasizes the importance of detainee operations to success during armed conflict. During the Gulf War (1990-1991), the Iraqi Armed Forces had an estimated military personnel strength of 1 million, and coalition forces captured approximately 70,000 Iraqis as enemy prisoners of war (EPWs), most in the first 3 days.2 The named adversaries in FM 3-0, Russia and China, have estimated military personnel strengths of 1.5 million and 2.5 million, respectively.3 Preparing for conflict with either of those forces requires significant training for detainee operations and the complementary interrogation operations.

In April 2023, while forward deployed to Poland as Task Force Ready, the 504th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade (E-MIB) hosted a combined4 and cooperative5 interrogation and detention exercise. The Ready Anvil exercise assessed the 97th Military Police (MP) Battalion’s (BN’s) ability to establish and operate a detention facility while also evaluating the 303rd Military Intelligence (MI) BN’s ability to conduct intelligence operations in the same facility. To strengthen partner interoperability, the 303rd MI BN embedded several Polish human intelligence (HUMINT) collectors with its HUMINT teams. To heighten the exercise’s realism, Ready Anvil employed Russian-language contract linguists as both detainees and interpreters.

Nearly 300 individuals participated in the 11-day event at Drawsko Pomorskie Training Area (DPTA), Poland. Participants included—

- U.S. Army MP and MI personnel.

- A Polish HUMINT team.

- Contract linguists.

- 504th E-MIB support staff and role players.

- Other U.S. Army role players and observer-controllers.6

- Other invited observers.

The exercise scenario pit multiple NATO corps against fictional Donovian Forces along Poland’s border at the onset of an armed conflict. The first several days focused on cooperative training between the MI and MP participants (to include foreign partners) and concluded with cooperative rehearsals of facility battle drills, such as riot procedures. The next two days were a crawl-start to the exercise followed by a one-day pause to celebrate Easter. The culminating exercise was a 4-day event with 24-hour operations as the MP force detained over 30 enemy personnel while the MI Soldiers executed intelligence operations.

Cooperative Training

Cooperative training, specifically concurrent detention and interrogation operations training, between MI and MP units does not occur often enough. Ready Anvil was the first opportunity for most MI and MP participants to collaborate in a cooperative detention and interrogation exercise. Although some participants had previous experience working in a fixed facility, none had experience establishing a detention facility or initiating interrogation operations in a new facility. Most often MI and MP units conduct detention and interrogation operations exercises without each other’s support. Ready Anvil taught both the MI and MP participants important operational lessons as well as lessons in how to conduct a cooperative detention exercise.

MP units conduct detention exercises regularly to validate the detainee operations core function. FM 3-63, Detainee Operations, guides the conduct of Army detention operations and provides considerations for planning detainee operations and facilities. It, therefore, becomes the basis for each facility’s standard operating procedures (SOPs). Additionally, FM 3-63 and FM 2-22.3, Human Intelligence Collector Operations, contain similar tables outlining the different responsibilities for MPs versus HUMINT collectors from the point of capture, through evacuation, to detention facility tasks.

Establishing the Detention Facility. In the exercise scenario’s operations order7, V Corps tasks the 97th MP BN with establishing a temporary theater internment facility in central Poland and tasks the 303rd MI BN with conducting interrogation operations in that facility. Other MP units attached to subordinate divisions within the V Corps area of operations would bring detainees to the newly established detention facility.

The Polish Armed Forces identified and provided four buildings on DPTA to serve as both lodging and training facilities. The largest building would be the detention facility—a 3-story structure with approximately 12 rooms on each floor. As part of its evaluation, the MP BN determined the facility’s layout and operations in consultation with the MI BN for its requirements. The MP BN dedicated the first-floor hallway to in-processing, interrogation booths, and an interpreter room. Detainee cells with a guard booth in the middle comprised the second floor, while two additional cells were on the third floor along with the MI personnel. Detention cells doubled as detainee sleeping quarters because the detainees were confined continuously once the exercise began. This configuration remained in place throughout the event and proved effective toward meeting the objectives.

Coordinating Operations. The guard force of six MP squads began controlling access to the detention facility during the crawl-start, making it imperative that the access roster listed all personnel and that they observed all rules of the facility. Only the observer-controllers had mostly unlimited access throughout the facility. While the exercise participants largely ignored the observer-controllers, all others observed the rules of the detention facility. This included routine lockdowns of the floors and stairwells as the MPs moved detainees. With the guard force working rotating shifts, following established protocols was critical. Exercise staff and participants constantly encountered different MPs; therefore, consistent conduct was essential.

Coordinating detainee movement with the MPs for screening or interrogation seems like a trivial step—particularly to HUMINT personnel that normally conduct interrogation exercises absent a guard force. The guard force, however, was responsible for all care and custody of the detainees. With the MPs running realistic, continuous detention operations, it quickly became clear to the MI personnel that windows for speaking to the detainees would be limited. Determining the correct mechanism for coordination proved challenging because the MI and MP personnel lacked a source of digital communication with each other, and requests needed deconfliction through multiple levels of both the MI and MP operations. Following the established SOPs proved crucial for successful coordination.

Human Intelligence Collection at a Detention Facility. Interrogation exercises normally operate on a controlled schedule, which allows for precise timing of screenings, interrogations, and injects by the exercise control element. Ready Anvil showed that an interrogation exercise in conjunction with a detention exercise provides no such dependable regularity. While exercises at combat training centers also provide irregularities in timing, they do not attempt to simulate a long-term holding facility. The dynamic nature of friendly force actions combined with the unpredictability of finding human sources (detainees or displaced persons) on the battlefield leads exercise planners to ignore or minimize scripting and injecting of HUMINT roles into brigade and higher-level exercises. Unfortunately, this leaves some combat arms officers believing that HUMINT lacks significance during armed combat. Exercises like Ready Anvil can demonstrate the value of interrogation operations outside of combat training centers where the condensed timeline does not allow for the real-life inevitability of long-term EPWs.

Organizational Separation between Military Police and Military Intelligence. The corps is the lowest echelon to have both organic HUMINT and MP elements; the alignment of these elements to subordinate units varies greatly. For example, III Corps has both a subordinate MP brigade and an MI brigade. III Corps also has four subordinate divisions that manage numerous brigade combat teams, each controlling a HUMINT element assigned to the brigade engineer BN’s MI company. Each MP brigade subordinate BN aligns to a division, and each MP company aligns to a brigade combat team. MI brigade subordinate BNs support corps and division headquarters, which do not receive direct support from MP units. Despite these variations, MI and MP units have opportunities to collaborate, such as during cooperative trainings like Ready Anvil.

Role Players in the Detention Exercise

In a typical interrogation exercise, role players study their roles until their scheduled screening or interrogation. Role players in a detention exercise must play their role the entire time. They do not know when they will meet with interrogators until the MP guard force moves them to an interview room. These unknowns in the timeline made it challenging for the Ready Anvil role players to learn and memorize their roles. It was also difficult for the exercise control element to monitor the progress of interrogations in terms of both role player performance and amount of intelligence revealed. Because of these complexities, Task Force Ready allowed the role players to keep printed role notes that were off-limits to both the MI and MP participants.

Soldiers from the 504th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade, the 97th Military Police Battalion, and partner nations at the conclusion of the Ready Anvil combined interrogation and detention exercise held on Drawsko Pomorskie Training Area, Poland, in April 2023. (U.S. Army photo).

Contract Linguists. Task Force Ready coordinated with the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) to contract Russian-language linguist support. INSCOM was able to contract 16 of the 32 linguists requested; 11 served as detainees and 5 served as interpreters. Contract linguists normally serve as interpreters, but training the remainder as detainees, primarily EPWs, required more effort. Most of these linguists were Ukrainian civilians with little knowledge of the military, which added to the training challenge.

The contract linguists could only work for 12 hours each day. A shortage of rooms on DPTA required the linguists to lodge off-site, which further limited their time with an hour spent commuting. This left only 11 hours each day that the linguists were in the detention facility, and nearly all their mandatory events (meals, hygiene, recreation time) occurred during the day. Consequently, MI personnel prioritized interrogating the contract linguist role players during the day and left interrogating the service member role payer for overnight.

Using Russian-language linguists as role players not only allowed the MI participants to practice and validate a critical HUMINT task, but it also forced the MP personnel to work through interpreters. Additionally, the MI BN exercised another critical task in managing the linguists. Counterintelligence agents trained on one of their critical tasks by conducting interviews with the linguists to vet them for employment. Pairing the best interpreter for interrogations with EPWs became an additional real-life task embedded in the training because some linguists lacked familiarity with military terminology.

Service Member Role Players. Task Force Ready provided 13 service member role players and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment provided 9 role players from their MI company. So me of these individuals had served as role players for interrogation exercises before, but none had served as role players in a detention exercise. The lack of lodging on DPTA necessitated in-processing the service members on the first day of the culminating exercise, then the MPs locked down the detention facility. Although the MP force conducted themselves professionally, the physicality and frequency of searches the detainees endured surprised the role players. For at least one hour each day, however, they were allowed to be “out of role,” given access to their phones, and permitted to socialize.

Managing Role Players. On the first day, the exercise control element briefed all role players on expectations and interviewed them to determine the best fit for each role. At the end of the day, the exercise control element gave each role player a packet to begin studying their role. This afforded the role players three full days to study with daily touchpoints from the exercise control element or the observer-controllers. Beginning on the fifth day, 10 role players processed into the detention facility each day until all role players were detained. The MP exercise control element requested the detainees arrive in groups of two or three throughout the day and night. After the MPs processed the detainees, MI personnel could initiate procedures for screening and interrogation.

Once management of the role players passed to the MPs outside the detention facility, the exercise control element had significantly less control over them than in a typical interrogation exercise. While the exercise control element and observer-controllers could access the role players in their cells and monitor interrogation sessions, it was impossible to monitor every interaction with the MI and MP personnel. The exercise control element advised role players to remain flexible, embrace their roles, and adapt to the environment during interrogations. They did not give the role players specific instructions about when to divulge information to the interrogators. Some role players misunderstood this flexibility and expanded their roles outside the interrogations and conspired to start a riot. While the riot never occurred, this unscripted event took time away from interrogations focused on intelligence gathering.

The contract linguists and observer-controllers lodged off-site because of limited space on DPTA. This caused the MI personnel to interrogate the contract linguist role players during the day and the service members at night. Because the MI unit operated both day and night shifts, the night shift personnel had little opportunity to interact with the contract linguists. Additionally, the observer-controllers only worked the day shift, affording them limited opportunities to observe and coach the night shift.

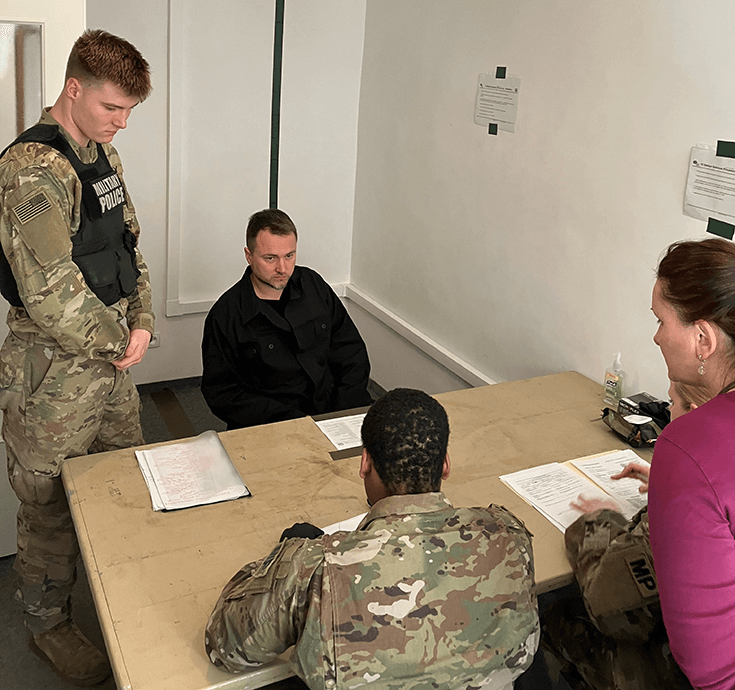

Military police from the 97th Military police Battalion process a contract linguist role player into the detention facility while another contract linguist serves as an interpreter during the Ready Anvil combined interrogation and detention exercise held on Drawsko Pomorskie Training Area, Poland, in April 2023. (U.S. Army photo).

Recommendations

Ready Anvil was a successful exercise that produced enhanced SOPs for both the MI and MP participating organizations. The most important take away from this experience was that the Army should consider making this an annual exercise. Additionally, future iterations could benefit from embracing the following recommendations for the detention facility battle rhythm and SOP, role player and observer-controller management, and scenario development.

Battle Rhythm Synchronization and Standard Operating Procedures. MPs operate detention facilities and MI personnel need to conduct interrogations within those facilities. The greater the coordination between these two entities, the greater the ability for the Untied States and allied forces to consolidate gains. Key areas of coordination to address are battle rhythms established by the MP force, shared SOPs for the facility, and defined procedures for the movement of detainees to interrogation booths.

Role Player and Observer-Controller Management. Interrogation exercises are only as good as the role players involved. The first suggested change is to split all role players into day and night shifts. This would avoid an excessive burden on the role players and give the exercise control element more accessibility to work with all of them. Similarly, allocate lodging away from the detention facility for the role players prior to entering detention as well as on-site lodging for the observer-controllers. This would provide greater flexibility for the introduction of role players into the detention facility and better observer-controller coverage for night operations. Finally, provide more in-depth training to the role players on enemy characteristics than what is in standard roles for short-term exploitation.

Purpose-Built Scenario. Future iterations require a scenario and roles designed to be distant in time and space from the forward line of troops (FLOT). The scenario and scripts provided by the INSCOM Intelligence Training Center were crucial to this exercise’s success. The request, however, did not define the phase of the battle nor the location of the detainee holding area. With the reach of modern firepower and the related interest in speedy removal of EPWs far from the FLOT, the timeline of field and fixed facility interrogations will expand. Review of World War II examples indicate that HUMINT may have its first prolonged exposure to EPWs hundreds of miles and multiple countries from the FLOT.

A corps-level scenario for large-scale combat operations should feature a few high-ranking and technically oriented EPWs mixed with high numbers of low-ranking forces. Requirements should be primarily strategic, and the goal of HUMINT operations should be efficiency in quickly processing the typical EPWs. Identifying these parameters and goals for the next exercise will assist in development of a relevant scenario, roles, and master scenario event list. The master scenario event list should be coordinated with the MP exercise control element to complement cooperative training.

Conclusion

Ready Anvil succeeded in addressing the capability gap identified by the 504th E-MIB commander. Throughout the competition-crisis-conflict continuum, combat arms units train to fight or fight in the same fashion. MP and MI (specifically HUMINT) units fulfill distinct functions depending on where the Army is at on the continuum. Following the “No MI Soldier at Rest”8 mantra of the former Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence (G-2) of the U.S. Army, LTG Mary Legere, it becomes easy to focus on the other HUMINT functions when not in conflict. However, the first half of LTG Legere’s guidance was “No Cold Starts.”9 To meet that intent, MI and MP units need to balance operating in competition and crisis with training for large-scale combat operations to consolidate gains effectively when that moment arrives.

Endnotes

1. Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 1 October 2022), 6-19–6-20.

4. Combined referring to the multinational partner organizations training together.

5. Cooperative referring to the military intelligence and military police units training together.

6. The Military Intelligence Readiness Command, the 66th Military Intelligence Brigade-Theater, and the 44th Special Forces Assistance Brigade generously provided observer-controller support for this exercise.

7. The U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command Intelligence Training Center created the scenario and roles for Ready Anvil.

Author

CW3 Kyle Clark is the human intelligence technician for the interrogation section of the 163rd Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Battalion at Fort Cavazos, TX. His previous assignments were at various unit echelons to include brigade combat team military intelligence (MI) company, MI brigade-theater, and Army Service component command. CW3 Clark has a master of arts degree in international relations from American Military University.