Sacred Speech in Future Armed Conflict

By Chaplain (Major) Brandon Denning and Chaplain (Major) Daniel Werho

Article published on: May 1, 2024 in the Chaplain Corps Journal

Read Time: < 15 mins

The battlefield of the future will be complex. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza already demonstrate the incredible complexity of war as reflected in the new multidomain operating concept.1 Chaplains have always provided ministry amidst the trauma, anxiety, uncertainty, and despair of war. The development and deployment of new technologies are adding to the complexity. Multidomain operations introduces further complexity with combined arms employment of space and cyberspace capabilities. Does this mean that the mode of sermon delivery will change? Possibly. However, we contend that chaplains cannot rely on leveraging these emerging technologies to deliver religious support. Instead, we focus on what we know will be constant: the human dimension.2 We argue that, in future operations, chaplains need to be prepared to use sacred speech that is simple and adaptable for tactical purposes, while still addressing the complexities of the human dimension of war. In this paper, we explore the complexities of the future battlefield and offer a model that navigates these complexities.

The Future Battlefield

Space and cyberspace domains will change the way sacred speech is delivered on the battlefield. Given technological advances and recent experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, one potential solution for chaplains seeking to reach their Soldiers dispersed across a future battlefield might be virtual sermons and worship services. However, FM 3-0 states that "peer threats employ networks of sensors and long-range massed fires that exploit electromagnetic signatures and other detection methods to create high risk for ground forces, particularly while they are static."3 For example, a Ukrainian battalion was destroyed by long-range precision rockets shortly after a drone was spotted observing their location.4 Soldiers will not be able to amass in large groups for any period of time without becoming a target. Instead, Soldiers will be dispersed to prevent detection through hostile air and space assets. At the same time technology will be limited, exploited, and leveraged by both the U.S. and the enemy. Internet connectivity will likely have a limited bandwidth dedicated strictly for current operations. Cell phones will be unusable and if they are used, the results could be deadly.5 Chaplains cannot expect to rely on technology to deliver sacred speech.

Chaplains need to formulate sacred speech in a condensed and adaptable form. The Army calls this technique the "BLUF" (bottom-line-up-front).The technique is designed to communicate concepts briefly and clearly. In homiletics, this technique is the called "The Big Idea."6 Using the BLUF or Big Idea technique allows for a variety of sermon structures and provides one central meaning to the sermon. In a large-scale combat operations (LSCO) context, this technique immediately informs the Soldier of the sacred text and main idea. The chaplain must adapt by delivering the conclusion at the beginning of the sacred speech. This is important in the case of an interruption. Then, the Soldier can later reference the sacred text and associate a meaning to it. In other words, the chaplain must structure the sacred speech in a way that it can be presented in full length or abbreviated, if required, without losing meaning. The message can be delivered in-person, or the message might be passed along through formations; possibly delivered by first-line leaders or even designated Soldiers. On the future battlefield, chaplains will need to be creative in developing means of delivering sacred speech in a way that is tactically sound to avoid putting Soldiers at risk.

There is a complex human element to every decision that must be made in war. War is not just about hardware.7 Humans have a will to hope, a will to fight, and a will to overcome overwhelming odds. Despite tactical constraints, chaplains still need to address the complex realities of the human dimension of war. This feels like an impossible task in light of the nature of today's realities. Soldiers' lives can change in an instant based on media, social media, politics, propaganda, family realities, and a myriad of other factors. How can chaplains deliver real, relevant, and brief sacred communications to the people in their care who are scattered across the front lines?

Amid chaos and when all the formalities are stripped away, the enduring elements of sacred speech remain. There will be people who want to worship God. There will be a sacred text. And there will be an existential need. If the chaplain is not there to bring these elements together, the Soldiers surely will, even if it is in small group gatherings. The point here is that the existential questions emerge through the experience of war. These questions will ultimately drive Soldiers of faith to a sacred text one way or the other. This means that chaplains must have a solid theology of suffering that speaks with relevance to the existential questions of war.8 This is the challenge the Corps faces.

In our experience of supervising chaplains, one of the mistakes we witness is the inability to transition to the existential needs of the Army during a combat scenario. Often the sacred text does not relate to the battlefield context, military language and illustrations are overdone, and the sacred speech is too long. There are some unchanging constants that should be predictable on the battlefield and in the lives of Soldiers. Chaplains should prepare messages that address these constants, such as issues related to stress, grief, trauma, fear, and suffering. Chaplains should also consider Soldiers' physical circumstances such as exhaustion, hunger, and distractions. Yet, on the future battlefield, chaplains may be unable to be present on a regular basis with all their Soldiers.

With that in view, messages should be repeatable to small groups of Soldiers multiple times a week or even within a day. We suggest chaplains consider partnering with Soldiers on the front lines to empower them as lay leaders. Chaplains should consider training and equipping their lay leaders. This approach may be uncomfortable for some chaplains. However, as a Corps and as individual chaplains we must adjust to the future battlefield where chaplains will be scarce, and survivability will be an operational premium for the command. Like most challenges, this train-the-trainer (T4T) model also presents opportunities. Chaplains can gain relational capital through the training process. Another benefit of this approach is that the chaplain's message will be mediated through the lay leader's experiences on the front lines. After all, the lay leaders will be living side-by-side with their peers on the battlefield.

Regarding content, chaplains serving on the battlefield of the future need an approach to sacred communication that gets straight to the existential questions and draws on sacred texts that answer those questions. Regarding form, chaplains serving on the battlefield of the future need an approach to sacred communication that is teachable and accessible to everyone. It must be portable and flexible enough to integrate with daily study and be deliverable in various small group settings.

The Conversational Model

To meet the challenges of this battlefield context, we propose The Conversational Model. This model was created and validated by Chaplain Denning in 2010 during Operation Hero Recovery, Afghanistan. Although it has not been tested in LSCO, Operation Hero Recovery was a 72-hour operation that included a mass casualty event. It is a real-world battlefield-tested approach to sacred communication.9 The Conversational Model is unique in the way it incorporates a hybrid delivery of monologue (explaining the text) combined with a facilitated dialogue all focused on the existential question addressed by the sacred text. Not to be confused with other dialogical approaches,10 it is not a solely facilitated model where interpretation is the task of the audience. Conversational homiletics is not new in and of itself but the focus, structure, and the elements of delivery for this model are unique. It is important to note that the chaplain does the exegetical work beforehand and can package it to equip front-line leaders when battlefield circulation is limited.

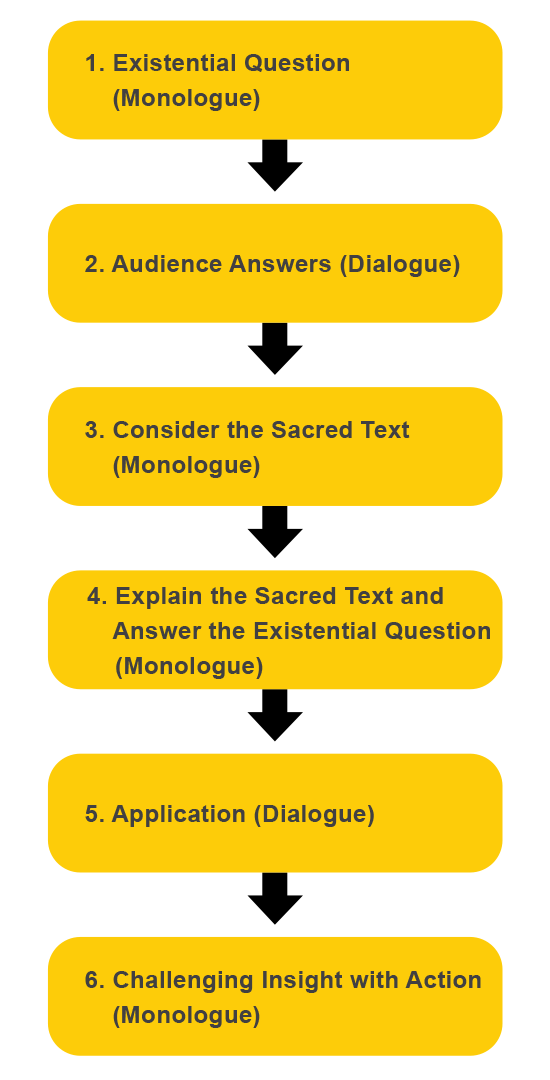

What makes this model useful is that it is informal, provides flexibility regarding length, assesses Soldiers' spiritual maturity through discussion, and is repeatable with little effort. For the Soldier, a conversational approach gains and maintains attention, feels collaborative through active participation, and provides practical application. The structure of the Conversational Model provides a logical and linear path. Below is a depiction of this path.

-

Existential Question (Monologue): The chaplain or facilitator11 begins by presenting the main idea of the message as an open-ended existential question. The question brings unity to the entire model and is derived by isolating the subject while determining the theme of the sacred text. The existential question is the BLUF in the form of a question that the sacred text will answer. Thus, even if the message is interrupted, the chaplain can still provide the reference to the sacred text for further study. It is important for the chaplain to study and prepare (exegetical work) because questions might be asked for further clarity. The chaplain is just presenting the question while setting the conditions for it to be answered honestly and openly by the audience. It is not rhetorical in nature and should not be presented as such.

-

Audience Answers (Dialogue): At this point, the chaplain facilitates a discussion around the existential question. The responses that emerge may be unpredictable, so it is important to keep answers focused on the question. During this stage of the model the chaplain listens to the Soldiers' answers and rarely comments. This approach gives the chaplain the opportunity to learn how the existential topic impacts everyone, assisting the chaplain in assessing spiritual needs. Soldiers should be allowed to process and explore their ideas and concepts related to the existential question. The first time the model is used, a chaplain should expect it be uncomfortable, ask follow-up questions to bring clarity to the subject, and help Soldiers to see that this is not just a lecture. Working in this way allows chaplains to show Soldiers that their thoughts are important in understanding how the sacred text addresses real life situations. If Soldiers get off subject, the chaplain kindly asks them to stay on subject and consider revisiting those discussions later. Whatever direction the conversation goes, the chaplain needs to be cautious not to dismiss any answers.

-

Consider the Sacred Text (Monologue): Once the chaplain determines it is time, this section serves as a transition to explaining the text in relation to the question. The chaplain explains to the Soldiers why he or she thinks the question is important and related to the scriptural worldview. The chaplain could speak to his or her own experience or reference a current situation. The key factor in this section is for the chaplain to make a clear transition to considering how the sacred text addresses the existential question. Soldiers should realize that this is the time to listen to the chaplain. Once this is done, the chaplain reads the section of sacred text to setup the next section.

-

Explain the Scared Text and Answer the Existential Question (Monologue): The chaplain explains the sacred text and its historical, cultural, and literary context. This should be brief and based on the chaplain's exegetical work. With the text and its context in view, the chaplain explains how the sacred text directly answers the question.

-

Application (Dialogue): In this section, the chaplain addresses the application question of "what does this look like today?" The chaplain invites the Soldiers to either participate in an exercise to reinforce the sacred text's answer or to share personal illustrations of how it effects their lives.

-

Challenging Insight with Action (Monologue): This is the conclusion of the sacred speech. It is designed to transition from insight to action, which could be a variety of next steps. The chaplain provides his or her own action to how the sacred text relates to the existential question.12 If the message is distributed, this is where lay leaders receive experiential training. Finally, the facilitator provides an action that everyone could take based on the how the sacred text answered the existential question.

A CONVERSATIONAL MODEL EXAMPLE FROM A CHRISTIAN APPROACH

-

Existential Question (Monologue): "What does God expect of us?"

-

Audience Answers (Dialogue):Facilitation of the answers.

-

Consider the Sacred Text (Monologue): "We live in a world of expectations. We have expectations from our leaders, spouses, children, maybe our parents. Expectations impact our beliefs, our actions, and how we live our lives. It impacts the way we respond to war and suffering. It seems important to know what God expects of us. I think we can answer this question by looking at Matthew 22:36-39 (NIV)." Read Text "Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?" Jesus replied: "'Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.' This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.' All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments."

-

Explain Sacred Text and Answer the Existential Question (Monologue): The chaplain continues the monologue by explaining the context and providing exposition to answer the existential question. The exegetical work is prepared before the message.

-

Application (Dialogue): "Let's put this concept to a test." After stating this, the chaplain asks for volunteers to give one of the 10 Commandments. As the Soldier gives a commandment, the chaplain asks the others in the group how that commandment fulfills what Jesus said in Matthew 22:36-39. The chaplain may need to help provide a commandment(s) if needed. An example of this is “thou shall not covet” fulfills loving your neighbor as yourself.

-

Challenging Insight with Action (Monologue): “We all need to be careful about loving things more than God. I had a CSM say to his NCOs, ‘Love people and use things, don’t love things and use people.’ God’s expectation is for all of us to love Him and love each other.

This model will not work in all contexts, but it may be especially suited for the battlefield of the future.13 There are several weaknesses that need to be considered. First, the chaplain must manage time during facilitation. Consider setting clear expectations around time to help Soldiers stay focused. Tell Soldiers there can only be a certain number of comments due to time constraints. Also, consider asking the existential question then reference the text in case of interruption or if you know time is limited. Another weakness is that this model does not work well in large groups of Soldiers or with Soldiers who do not know one another. It is also important that the chaplain has an established relationship with the Soldiers.

Keep in mind that as a combat approach, this model is flexible. If time is restricted, all portions of facilitation (parts 2 and 5) can be removed, and the sermon remains monological. If the chaplain has a network of trained front-line leaders who understand this model, the chaplain can simply push out the exegetical work in a packageable format that the front-line leaders can adapt to their Soldiers’ context. Imagine a prompt sheet with the existential question and instructions on guiding the conversation with the sacred text and prompts for the monologues. This would look like the example provided above. This makes the model portable, teachable, adaptable, and focused on the BLUF.

Conclusion

The battlefield of the future will be constrained by technology and time. Traditional preaching models may be difficult to deliver or ineffective. The Conversational Model works within the constraints to address the existential questions that emerge in the context of war and suffering.14 Our approach is simple and adaptable and addresses the complexities of war. The Conversational Model fosters sacred speech that is real, relevant, and brief, regardless of who is delivering it. As the Army continues to train for future operational environments, religious support activities will be increasingly challenging, and their delivery may change. Our hope is that this article serves as a first step in a wider conversation around sacred communication in future armed conflict.

Author

Chaplain (Major) Brandon Denning enlisted in the Infantry in 1996 and became the 453rd Guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. He has a Master of Divinity in Biblical Languages from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and a Master of Arts from Columbia International University with an emphasis in preaching. Brandon deployed with the 82nd Airborne Division in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. He also served at Arlington National Cemetery, The Old Guard, Special Forces, Basic Combat Training, and as the Homiletics Instructor at the U.S. Army Institute for Religious Leadership. He is retiring and returning to the pastorate.

Chaplain (Major) Daniel Werho entered active duty as a chaplain in 2012. He holds a Master of Divinity from Denver Seminary in Pastoral Counseling and a Master of Theology from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Preaching. He served in aviation, signal, and psychological operations units with a combat deployment to Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. He currently serves as the Homiletics Instructor at the United States Army Institute of Religious Leadership in Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

Endnotes

1 Multidomain operations refers to “the combined arms employment of joint and Army capabilities to create and exploit relative advantages that achieve objectives, defeat enemy forces, and consolidate gains on behalf of joint force commanders.” Department of the Army, Operations (3-0) (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2022), 1-9.

2 Department of the Army, Holistic Health and Fitness (FM 7-22) (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2020).

3Department of the Army, Operations, 1-10.

4 See the case study in Operations, 2-9.

5 Rhoda Kwon, “Russia blames its soldiers’ cellphone use for missile strike that killed dozens,” NBC News, last modified January 4, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/russia-blames-soldiers-phone-use-ukraine-missile-strike-rcna64187.

6 Homiletics is the art and science of communicating any sacred speech that provides essential elements of religion that can include worship, observances, or religious education. It is deploying practical theology in a way that makes it useful and applicable.

7 Department of the Army, Operations.

8 We recommend all chaplains develop a formal theology of suffering through a group process prior to going to war. Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) is one option to work through a theology of suffering, but technical supervisors can also walk a cohort through a process as a part of training for war.

9 After use in combat, Chaplain Denning later noticed that the sacred speech lost authority and significance when defined by Soldier’s opinions of the meaning of the text. Most Soldiers were not familiar with inductive study approaches. During his time as the Homiletics instructor at USA-IRL, he worked to refine a useable model for use by any chaplain. Later, Chaplain Werho’s combat experience helped emphasize the importance of the existential question in the model.

10 This is not “Dialogue Preaching” as defined by Lucy Atkinson Rose nor is it Doug Pagitt’s “Progressive Dialogue.” See Lucy Atkinson Rose, Sharing the Word: Preaching in the Roundtable Church (Louisville, KY, Westminster John Knox, 1997) and Doug Pagitt, Preaching Re-Imagined: The Role of the Sermon in Communities of Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005).The sermon does not belong to the audience per se. It is driven by the text and the chaplain’s previous exegetical work. The audience participates providing insight and practical illustrations, but the goal is conveying the meaning of the text and preserving the authority of the Scripture.

11 For the sake of simplicity, both the chaplain or the facilitator are referred to as the chaplain for the rest of this explanation.

12 If this message is facilitated by a lay leader, it is important to have the facilitator do some personal reflection on the exegetical work provided by the chaplain.

13 This model is not recommended in a formal congregational setting such as chapel.

14 Examples of existential questions include: What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why am I doing this? Will I be punished for sin? Is there life after death? Why do we suffer? Can people change? Can people really be good? What is wisdom? How do I measure success? Can war be morally justified? What is the difference between killing and murder?