Is a Mobile Defense a Viable

Option for a BCT?

By LTC Jon Anderson

Article published on: October 18, in the Winter 2024-2025 Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time:

< 10 mins

Soldiers from the 2nd Mobile Brigade Combat Team, 101st

Airborne Division (Air Assault) maneuver their Infantry

Squad Vehicle at Fort Johnson, LA, on 16 August 2024.

(Photo by SSG Joshua Joyner)

Imagine a combat credible force capable of fighting

further, faster, and in the fiercest conditions, creating

dilemmas for the enemy to a degree which has never

been seen before: a force that is specifically designed to

fight and win in severely restrictive terrain, with the ability to

rapidly reposition forces with organic mobility assets across

the battlefield, and that could strike deep behind enemy lines

through expeditious air assault operations. This fighting force

is the 2nd Mobile Brigade Combat Team (MBCT), 101st

Airborne (Air Assault), and it’s changing the paradigm of large-scale combat operations (LSCO). During Joint Readiness

Training Center (JRTC) 24-10, 2/101 MBCT maximized the

opportunity to experiment and validate concepts in the world’s

premier training environment against a fierce opposing force

(Geronimo), resulting in tactical, operational, and strategic

implications for the U.S. Army. While this creative approach

validated many concepts within the Army’s transformation in

contact concept, it also revealed unexpected outcomes. One

unexpected outcome is that, through the use of the Infantry

Squad Vehicle (ISV), the ability to conduct a mobile defense

(a type of defensive operation typically limited to division or

higher formations) is now a viable option for a mobile brigade

combat team. Utilizing the operations process as a framework (plan, prepare, execute, assess), this article describes

the actions of 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment during

Operation Strike Fury defensive operations and how they

showcased the capability of the ISV to rapidly move forces

across the battlefield as a dedicated counterattack force to

create conditions for the offense and allow 2/101 MBCT to

regain the initiative.

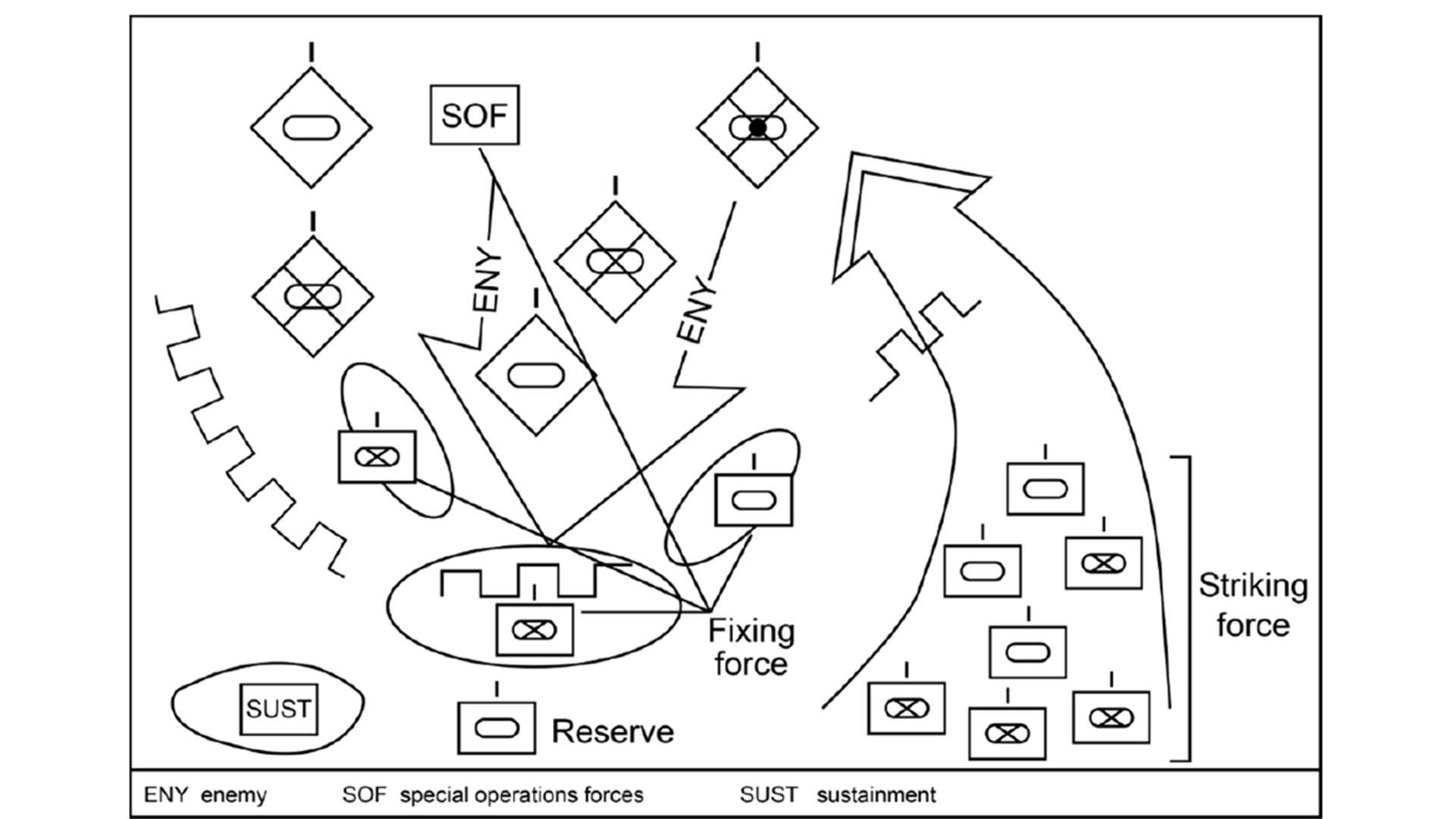

Figure 1 — Mobile Defense (FM 3-90)

Overview

It is extremely rare for a brigade combat team (BCT) to

conduct a mobile defense. Due to the resources required

and the size of the area of operations (AO), it is not typically

feasible for an element smaller than a division. However,

an MBCT, when properly task organized, contains all the

necessary resources to execute this type of defensive operation, to include reconnaissance assets, sustainment, and

an agile command and control structure. A mobile defense

is composed of three elements: the fixing force, the striking

force (where the majority of the combat power resides),

and the reserve. Chapter 10 of Field Manual (FM) 3-90,

Tactics, states that a “mobile defense focuses on defeating

or destroying enemy forces by allowing them to advance

to a point where the striking force can conduct a decisive

counterattack.” See Figure 1 for an

example sketch of a mobile defense.

In addition to the organization’s

available resources, there are three

key factors stated in section 10-3 of FM

3-90 that favored a mobile defense in

this scenario. The first is that frontage

assigned exceeds the defending force’s

capability to establish an effective area

or positional defense. Second, the depth

of the assigned area encourages attacking enemy forces to overextend and

move into unfavorable positions where

they are vulnerable to a counterattack.

Third, the time for preparing defensive

positions is limited. Although 2/101

MBCT did not deliberately plan a mobile

defense, over the course of the operation, the brigade implemented concepts

that closely resembled a fixing force and

a striking force to exploit the enemy’s

piecemeal attack.

Plan

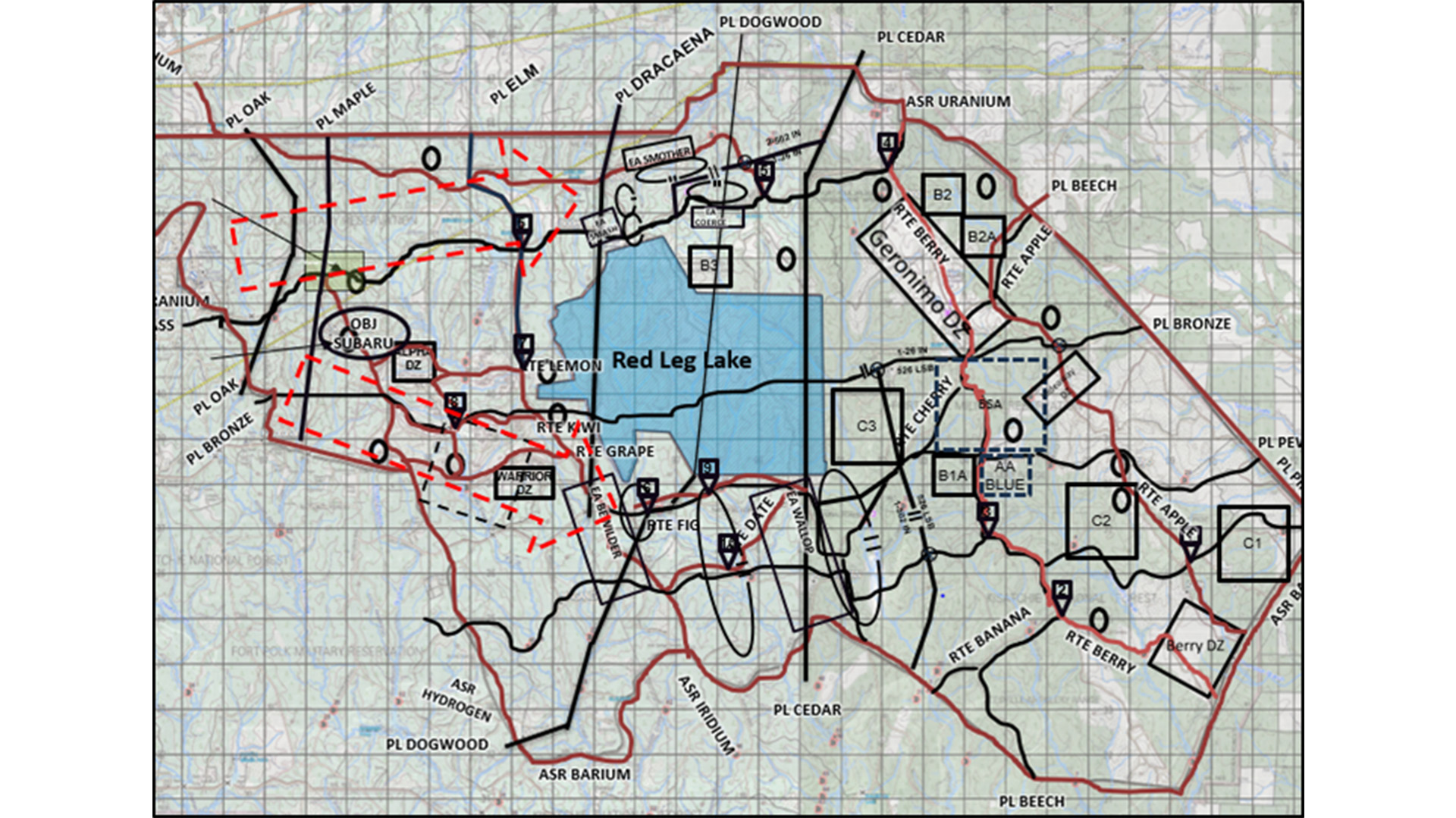

The Operation Strike Fury defense was originally

planned as an area defense tied to terrain in the

northern and southern portions of the brigade’s AO

and connected by a large natural obstacle, Red

Leg Lake, in the center (see Figure 2). However, as

conditions changed, to include enemy actions and

the brigade’s understanding of the terrain, the agility

and flexibility of 2/101 MBCT gave the commander

unique options. This ultimately led to a modified plan

that utilized significant portions of a mobile defense

concept. The capability of the ISV proved critical to

shaping the course of the battle and gave distinct

advantages to the MBCT throughout the defensive

operations.

The original operational concept included 2nd

Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment (+Charlie

Company, 1-26 IN operational control [OPCON])

and 1-26 IN (Bravo Company, 1-26 IN and Brazilian Pioneer

Company) conducting an area defense in the north, and

1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment conducting an area

defense in the south, to include a detailed deception plan

using decoy emitters and proximate positioning of elements

of 1-26 IN to the east and south of the AO.

The commander’s intent was to project the commitment

of two battalions to the south, forcing the enemy to pursue

a perceived vulnerability to the north, which would give the

brigade’s main effort a distinct advantage. Upon confirmation

of the enemy’s commitment of forces north, the plan was to

rapidly reposition B/1-26 IN from the south to the north more

than 30 kilometers utilizing their ISVs, providing a defense in

depth to destroy Geronimo in detail. For reference, the ISV

carries nine Soldiers, reduces Soldier load through storage of Class I and V, and can rapidly transport maneuver elements

through restricted or unrestricted terrain (about 15mph in the

training area at night).

Figure 2 — Operation Strike Fury Operational Graphic

With this planning consideration, 1-26 IN can completely

reposition its forces more than 30 kilometers in less than 90

minutes. This addresses the issue of a BCT not normally

having the resources available to execute a mobile

defense; the fixing force sets conditions while the striking

force maneuvers into position to close with and destroy the

enemy. Additionally, the Blue Spaders implemented several

tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that maximized

the capabilities of the ISV while mitigating risk of exposure

with the enemy. For example, while on the move, 1-26 IN

utilized small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS) 500-1,000

meters in advance of its formations to identify enemy locations.

Another tactic that proved effective was to utilize the Modi

system on the move when the enemy sUAS threat was

likely. While at the halt, or while moving into attack positions,

platoon formations would move into a herringbone formation off the road and immediately conceal their vehicles

with camouflage netting. This allowed the Blue Spaders to

maximize their light infantry capability by making first contact

with sensors and scouts rather than driving into an ambush.

This set the stage to move into the preparation of primary,

alternate, and subsequent battle positions in preparation for

the attack.

The operational requirements of the Infantry Squad Vehicle include the ability to carry nine Soldiers, a payload of 3,200

pounds, transportable by external sling load by a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, internal load/external lift by CH-47

Chinook helicopter, and exceptional mobility over all terrain, allowing infantry brigade combat teams to move with their

equipment over difficult terrain. (Photo by Michael J. Malik)

Prepare

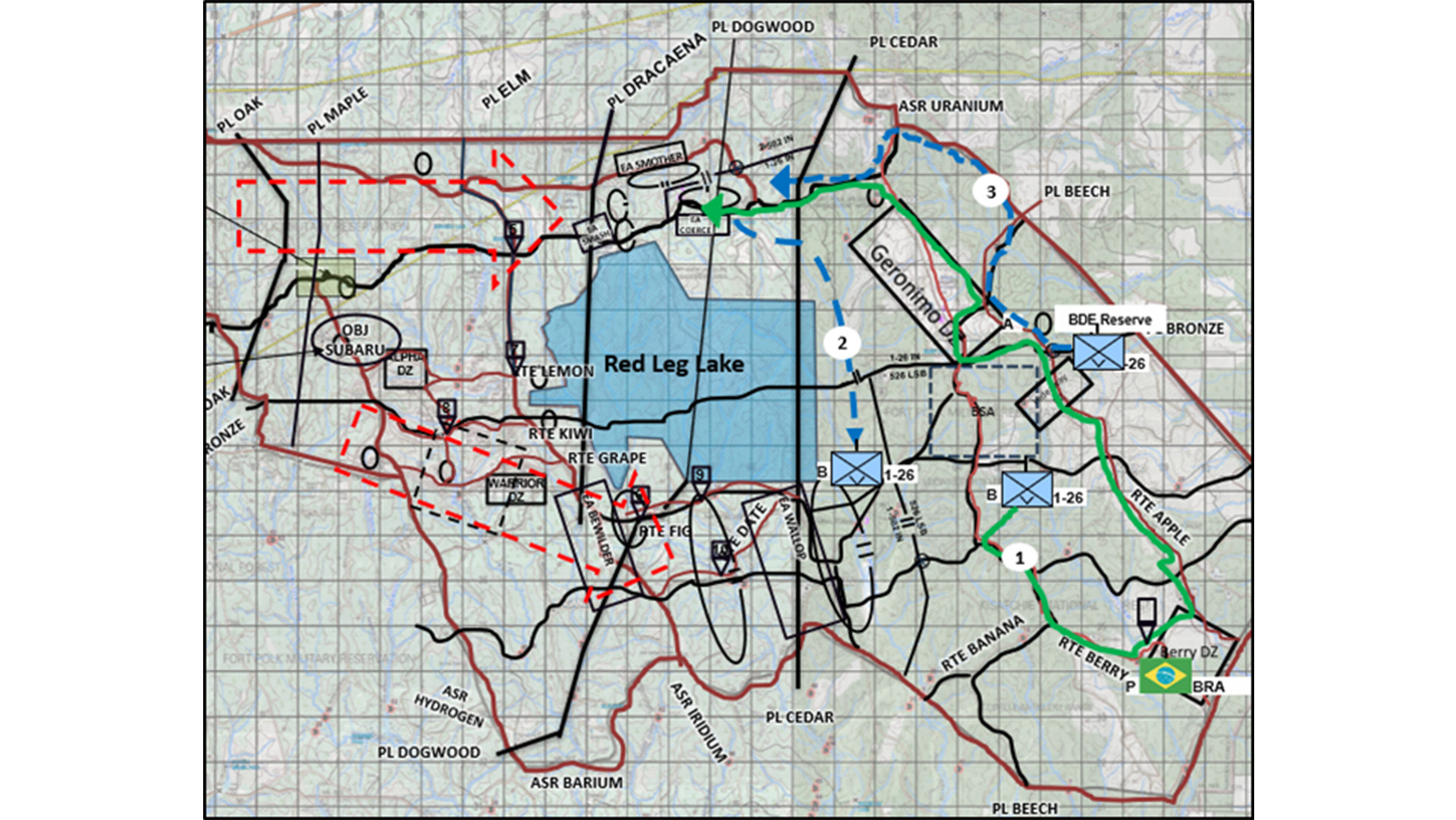

Indications showed an enemy counterattack from the

southeast of the brigade, and 1-26 IN executed a fragmentary order to secure the brigade’s flank. B/1-26 IN served

as the main effort for this phase and constructed four battle

positions along key terrain to destroy enemy forces as they

attempted to attack the brigade’s rear area. The company

then utilized its ISVs to position forces along a 5-kilometer

front and conducted engagement area (EA) development by

integrating obstacles, fires, and key weapon systems along

the enemy’s most likely avenues of approach. However,

the enemy situation changed so 1-26 IN utilized its ISVs to

reposition more than 175 Brazilian light infantry soldiers to

the north from Berry Drop Zone to provide a defense in depth

of 2-502 IN. Over the course of two 60-kilometer round-trip movements, B/1-26 IN transported Pioneer Company

soldiers into their new AO, where they conducted continuous

EA development throughout the period of darkness. These

soldiers were positioned at the right time and place to destroy

enemy forces should they break through 2-502 IN’s defense

(see Figure 3, #1, for scheme of maneuver).

Execute

During the execution of the defense, Pioneer Company

destroyed 14 enemy vehicles and killed more than 30 enemy

in their engagement area. Concurrently, the multi-purpose

company (M/1-26 IN) provided early warning and security to

its northern flank through the use of its scout platoon, loitering unmanned systems (LUS) platoon, and anti-tank platoon

serving as the battalion reserve. A/1-26 IN was positioned at

a central location to the east of Red Leg Lake, approximately

15 kilometers from northern or southern brigade defensive

positions. During the course of the battle, A/1-26 IN was

committed north to the interdict the enemy’s advance upon

their penetration of 2-502 IN’s defensive position, essentially

serving as a striking force in the mobile defense concept.

A/1-26 IN was able to occupy its battle positions in the north

in under 40 minutes and in position to destroy the remnants

of the enemy formation. Simultaneously, B/1-26 moved more

than 20 kilometers to the south to conduct a counterattack

to the rear of 1-502 IN, as the enemy showed indications of

penetrating defensive positions to the south (see Figure 3,

Route #2 and #3 for scheme of maneuver).

Figure 3 — This graphic depicts B/1-26 IN’s movement of the Brazilian Pioneer Company

(Route #1, shown in green), B/1-26 IN’s follow-on movement to its ambush position (#2,

shown in blue), and A/1-26 IN’s movement to its ambush position (#3, shown in blue).

Assess

Throughout the operation, the 2/101 MBCT commander

exercised options and positioned forces in a way that the

enemy was not expecting. This caused multiple dilemmas

for the enemy and desynchronized their attack at echelon.

Although this operation was initially planned as an area

defense, the brigade executed components of a mobile

defense that set conditions to rapidly transition to the offense.

The ISV proved to be a decisive capability for the brigade,

and the Blue Spaders demonstrated that through this platform, and the relentless pursuit of the enemy, the U.S. Army has a new way to fight and win

in the most austere conditions.

Without this capability, the

brigade would have had limited

options to exploit vulnerabilities

of the enemy and would have

been forced to commit to one

course of action in a vast area

defense. With this new level

of awareness in capability, an

MBCT should deliberately plan

a mobile defense — properly

weighting the fixing, striking,

and reserve force — to find, fix,

finish and follow through with

destruction of the enemy.

JRTC 24-10 was truly a

crucible experience for the individuals and organizations that

tested themselves in the heat

and pressure of Fort Johnson,

LA. 2/101 MBCT used this

rotation as an opportunity to

experiment and innovate with

new equipment and TTPs that

revealed critical lessons learned

for the U.S. Army. The lessons

learned throughout the planning, preparation, and execution

of the defense highlighted the fact that it is feasible for a

MBCT to execute a mobile defense. With further refinement

and innovation, this concept can be widely applied to similar

formations and executed in the most austere environments.

This new capability creates multiple dilemmas for the enemy,

and it is changing the paradigm in how an MBCT fights. This

crucible experience during JRTC 24-10 produced many

tangible results, with the most important being a more lethal

formation, ready to fight where we are told, to win while

relentlessly pursuing our rendezvous with destiny.

Author

LTC Jon Anderson currently commands 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry

Regiment, 2nd Mobile Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne (Air Assault),

Fort Campbell, KY. He previously served as a brigade operations officer for

the 4th Security Force Assistance Brigade, where he was responsible for

the unit’s security cooperation efforts across the U.S. European Command

theater of operations. LTC Anderson’s other assignments include serving

as commander of C Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Security Force Assistance

Brigade; senior associate athletic director at the United States Military

Academy (USMA); operations officer and executive officer of 1st Battalion,

41st Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, with a deployment in support

of Operation Freedom’s Sentinel; Soldier-Athlete and officer-in-charge of the

U.S. Army World Class Athlete Program’s wrestling detachment and the Total

Soldier Enhancement Training (TSET) program; commander of D Company,

2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry, and F Company, 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry

Regiment; and platoon leader and executive officer in A Company, 1st

Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, to include a deployment to Iraq in support

of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He earned a bachelor’s degree in geopolitics

from USMA and a master’s degree in psychology, sport and performance

specialization.