Training–Focus on Fundamentals

By CPT Ty R. Dawson

Article published on: October 1st 2023, in The Oct-Dec 2023 Edition of the Aviation Digest Professional bulletin

Read Time: < 17 mins

Soldiers train for wet gap crossing missions to prepare for large-scale combat operations. U.S. Army photo by CPT Anthony Grady.

We are going to be an organization that focuses on mastering the fundamentals. As Army leaders, we often hear this vision statement at meetings and quarterly training briefs. Do we really know what that vision entails or how to achieve it? There are at least two ongoing major events that give us reason to pause and think about the fundamentals of our profession. First, the world watches as a powerful Russian military fails at the fundamentals of warfare with disastrous consequences for its personnel and wanton disregard for innocent Ukrainian civilians. Second, while that war rages on and threatens greater conflict, we are transitioning to a multidomain operating concept while focusing on large-scale combat operations (Department of the Army [DA], 2022, p. ix). We cannot afford a haphazard approach to achieving that oft-stated vision of an organization focused on mastering the fundamentals. Without a simple, coherent strategy that includes SMART—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely goals, (Doran, 1981) the Army, along with Army Aviation, risks losing its superiority over its adversaries.

I wrote this article to help commanders and other leaders assess whether their organizations actually focus on mastering the fundamentals by providing information and ideas regarding the following:

- Identifying the fundamentals units must strive tomaster

- Providing a simple, multi-echelon trainingstrategy

- Linking aviation training to mastering thefundamentals

- Fighting for whitespace

Identifying the Fundamentals

Field Manual (FM) 7-0, “Training,” guides commanders to use a prioritized training approach to maximize limited time and scarce resources to achieve proficiencies supporting their unit’s mission. “Every unit is unique, but the fundamentals of shoot, move, communicate, and survive apply to all types of formations and serve as the basis for training prioritization”

(DA, 2021, p. 2-1). Based on this guidance, shoot, move, communicate, and survive are the fundamentals Soldiers and their units must master to maintain a tactical advantage. If a training event does not include a task supporting at least one of these fundamentals, it should not be prioritized. The fundamentals, as listed in FM 7-0, assist commanders with crafting a training strategy starting at the individual level and culminating at the desired echelon.

Ultimately, commanders want their units to be able to shoot, move, communicate, and survive in diverse environments while achieving the desired end state within the confines of the commander’s intent. This means being able to complete a mission-essential task (MET) at night with a dynamic and complex threat and four or more operational variables. Field Manual 7-0 describes a MET as “a collective task on which an organization trains to be proficient in its designated capabilities or assigned mission” (DA, 2021, p. 2-1). For aviators, this means not only being proficient at the individual tasks (IT) listed in the Aircrew Training Manual (ATM) but also the supporting collective tasks (SCTs) found in the Training Evaluation and Outline (TE&O) for a given MET.1 For commanders, this means crafting a simple and robust training strategy for your organization.

Multi-echelon Training Strategy

This article will use an Air Cavalry Troop’s (ACT) METs to create a draft training plan. The process begins with first understanding your unit’s overall mission and capabilities. Many resources exist to address this, but I recommend starting with FM 3-04, “Army Aviation,” (DA, 2020). Among other things, you will learn from this FM that an Air Cavalry Squadron (ACS), and subsequently, an ACT, “…provides accurate and timely information collection, provides reaction time and maneuver space … destroys, defeats, delays, diverts or disrupts enemy forces.” It explains further, “… the integration of RQ-7B UAS [unmanned aircraft system] at the troop level makes the ACS the best formation for conducting reconnaissance, security, and movement to contact as primary missions, with attack operations as a secondary mission” (p. 2-7).

Having developed a general understanding of your unit’s missions and capabilities, shift focus to understanding your unit’s specific METs. You will find your unit’s mission-essential task list (METL) on the Army Training Network (ATN) website.2 Recall that a MET is a “collective task on which an organization trains to be proficient in its designed capabilities or assigned mission,” and a METL is “a group of mission-essential tasks” (DA, 2021, p. 2-1). In other words, a unit’s METL includes those selected METs the Army expects a unit to perform in order to successfully complete the assigned mission. A unit’s METL provides the foundation for training.

Planning a multi-echelon training strategy requires knowledge of your unit’s mission, capabilities, and METs. After reviewing the relevant content on ATN, you will discover an ACT has the following METs:

- Conduct Aerial Screening Missions

- Conduct Aerial Movement to Contact Missions

- Conduct Aerial Reconnaissance Missions

- Conduct Expeditionary Deployment Operations

With limited time each month for training, how do you pick the correct METs to prioritize? Several things must be considered when pondering this question. First, ask yourself, “What does doctrine say?” For an ACT, FM 3-04 tells us that “reconnaissance, security and movement to contact” missions should be prioritized due to the integration of UAS at the troop level (DA, 2020, p. 2-7). Second, what culminating events or deployments are on the horizon? Consult the long-range training calendar to identify the next “big thing.” This could be a combat training center (CTC) rotation, troop external evaluation (EXEVAL), or an operational deployment. From there, backward plan to determine how much time you have to train your unit. Third, identify your unit’s mission in support of the upcoming event. Which METs will evaluators rate your unit on during an EXEVAL or, what missions are the supported unit at a CTC expected to assign? Finally, determine your unit’s current level of proficiency. Regardless of the mission assigned, could your Soldiers perform their mission at night, in complex terrain, with a dynamic and complex threat while integrating external capabilities? These questions are not all-encompassing but provide a starting point for determining which METs you need to prioritize. Having developed an understanding of your unit’s mission, capabilities, METs, and training priorities, you are ready to develop a training plan.

We are told that training is a commander’s primary responsibility, thus causing some to create their training plan in a vacuum devoid of input from other members of the organization. The Army intentionally structured units with key positions for expert personnel to support the commander with recommendations based on institutional knowledge and combat-tested practical experience. These key personnel include the standardization pilot (SP), aviation mission survivability officer, instructor pilots (IPs), and platoon leaders (PLs) to ensure they have a say in how the unit is trained. Your point of view of the unit as its commander is drastically different compared to the SP or PLs. Building trust by forming a strong working relationship with your team of experts is part of keeping your finger on the pulse of the organization. Input from these key personnel includes real-time feedback on many things, such as an honest assessment of your aviators’ proficiencies. Working together on a training plan is one way of building trust. Once complete, brief the entire organization, ask for feedback, and give others ownership of the plan. Not only does this help create buy-in by ensuring everyone has skin in the game but it also provides predictability to the extent a troop or company commander can control.

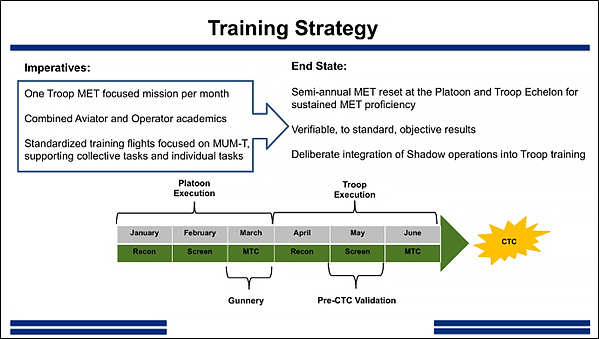

There are many methods for building a training plan. For instance, one way is to backward plan and publish it with an accompanying calendar in an easily digestible format no less than 6 weeks prior to the event. Planning early gives you time to create buy-in across the organization and make adjustments based on Soldier feedback. Figure 1 is an example visual aid that helps unit members understand the commander’s intent and training strategy. When published and shared early, it creates understanding by showing clear training imperatives, the training success factors, and how the training leads to the desired end state. The arrow along the bottom of Figure 1 shows a monthly rotation of METs and supporting training events leading to a final culminating event.

Figure 1. Example of a training strategy summary (Dawson, 2022a).

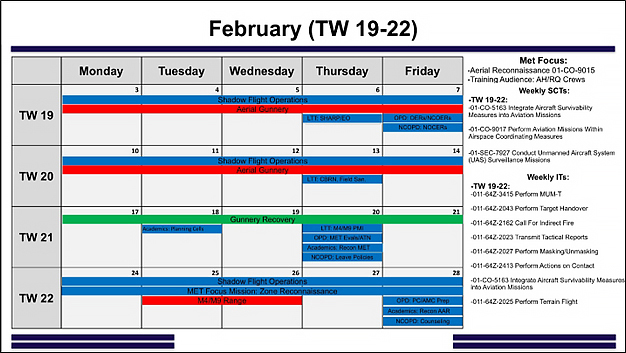

In Figure 1, a new MET focus is planned monthly, ensuring the organization can prioritize limited time and resources without being spread too thin. As shown in Figure 2, Conduct Aerial Reconnaissance has been selected as the monthly MET focus. Supporting collective tasks and ITs, selected from the reconnaissance TE&O, listed on the right of Figure 2, rotate monthly and provide focused training during regular training flights.

Figure 2. Example of a monthly training calendar (Dawson, 2022b).

Having these tasks listed on a kneeboard provides an easy grab-and-go product for aircrews to track their training during a flight. By providing these kneeboards, the unit is able to get the most out of their training flights and maximize the hours they have available. Instead of wasteful discussions the day of the flight about where everyone wants to fly to, aviators will have a focused list of tasks to train (Figure 3).

Preparation for a regular training flight should begin the day prior with a brief discussion led by the pilot-in-command (PC). As primary trainers, PCs should discuss with the pilots the tasks to be trained during the next day’s flight so they can be reviewed in the ATM. A fruitful discussion can then take place during the crew brief about where and how each task will be trained. The discussion need not be overly complex but should include the standards and procedures for the tasks to be performed. It could be as simple as identifying a remote training site where the crew will practice terrain flight, conduct simulated engagements, and culminate in a call for fire.

Look for efficiencies to be gained between the monthly kneeboard and an aviator or operator’s Commander’s Task List (CTL). Some of the tasks listed on the kneeboard may also be on the CTL, creating opportunities for completion during MET-focused training. Additionally, these kneeboards are not specific to manned aviation only and should be used for unmanned operators as well. The intent is not to limit how training is conducted or to stymie creativity; rather, it is to provide a starting point to ensure the unit is holistically working toward increased proficiency.

As previously mentioned, a well-constructed training plan creates buy-in and will provide opportunities for the audience to be invested in the success of their own training. To help facilitate weekly training flights, as an example, have the troop or company aviators each generate a simple grab-and-go concept of the operation for a selected MET. These can be kept on hand and provide simple scenarios covering the basics, enemy situation, mission, commander’s intent, etc., for the local training area. Not only will these provide another layer of realism but will make completing the tasks on the kneeboard more mission-focused and less check the block.

| Recon Task Checklist | Date: |

| Tail Numbers: | PC/AC: | PV/AO: | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Link 16 | Tail # | Status: |

| BFT | Tail # | Status: |

| Secure Comms | Tail # | Status: |

| AAG | Tail # | Status: |

| UR | Tail # | Status: |

| FCR/RFI | Tail # | Status: |

| SUPPORTING COLLECTIVE TASKS |

| 01-CO-5163 | Integrate Aircraft Survivability Measures into AV Missions |

| 01-CO-9017 | Perform AV missions within Airspace Coordination Measures |

| 01-SEC-7927 | Conduct UAS Surveillance Missions |

| Complete | INDIVIDUAL TASKS | # Iterations |

| | Perform MUM-T

011-64Z-3415 | |

| | Perform Target Handover

011-64Z-2043 | |

| | Call For Indirect Fire

011-64Z-2162 | |

| | Transmit Tactical Reports

011-64Z-2023 | |

| | Perform Masking/Unmasking

011-64Z-2027 | |

| | Perform Actions on Contact

011-64Z-2413 | |

| | Integrate Aircraft Survivability

01-CO-5163 | |

| | Perform Terrain Flight

011-64Z-2025 | |

| NOTES |

| |

Figure 3. Example training flight kneeboard (Dawson, 2022c).

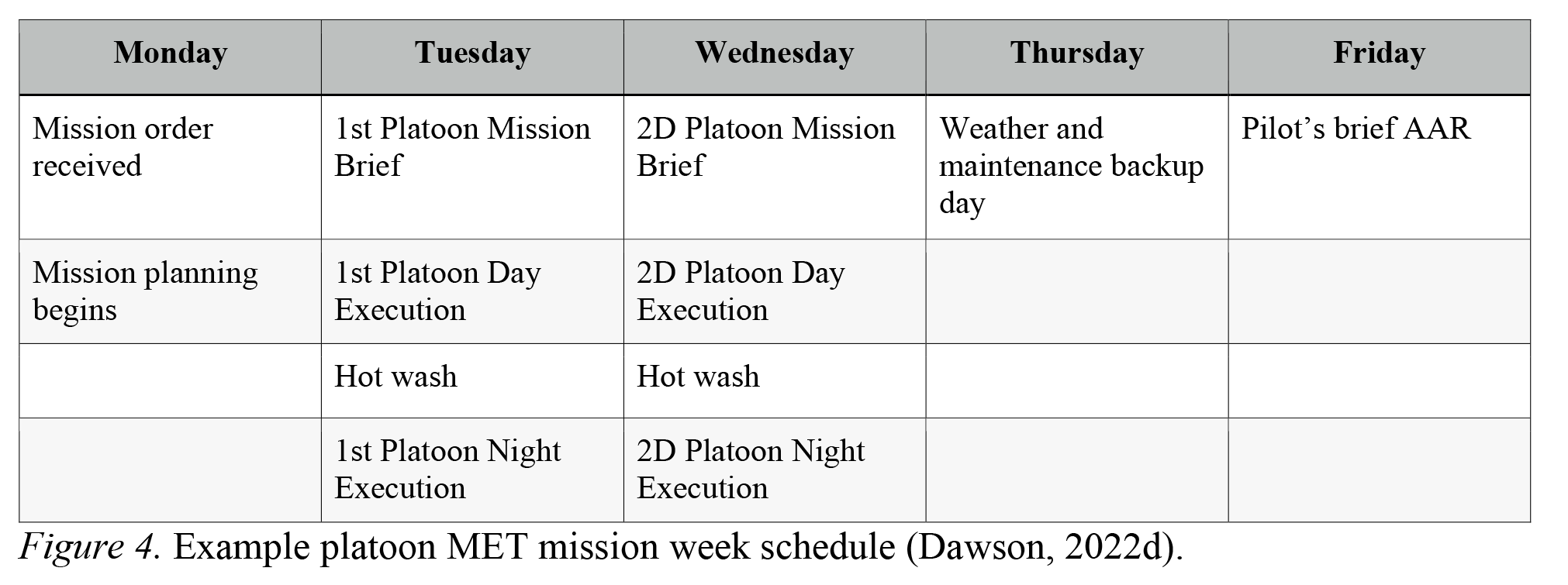

Once mission week has arrived, the MET mission is the focus for that week. It is important that other flights, such as annual proficiency and readiness tests, proficiency flight evaluations, and progression flights are scheduled for the other 3 weeks of the training cycle to maximize personnel availability, especially the SP and IPs. A platoon echelon mission week generally functions as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example platoon MET mission week schedule (Dawson, 2022d).

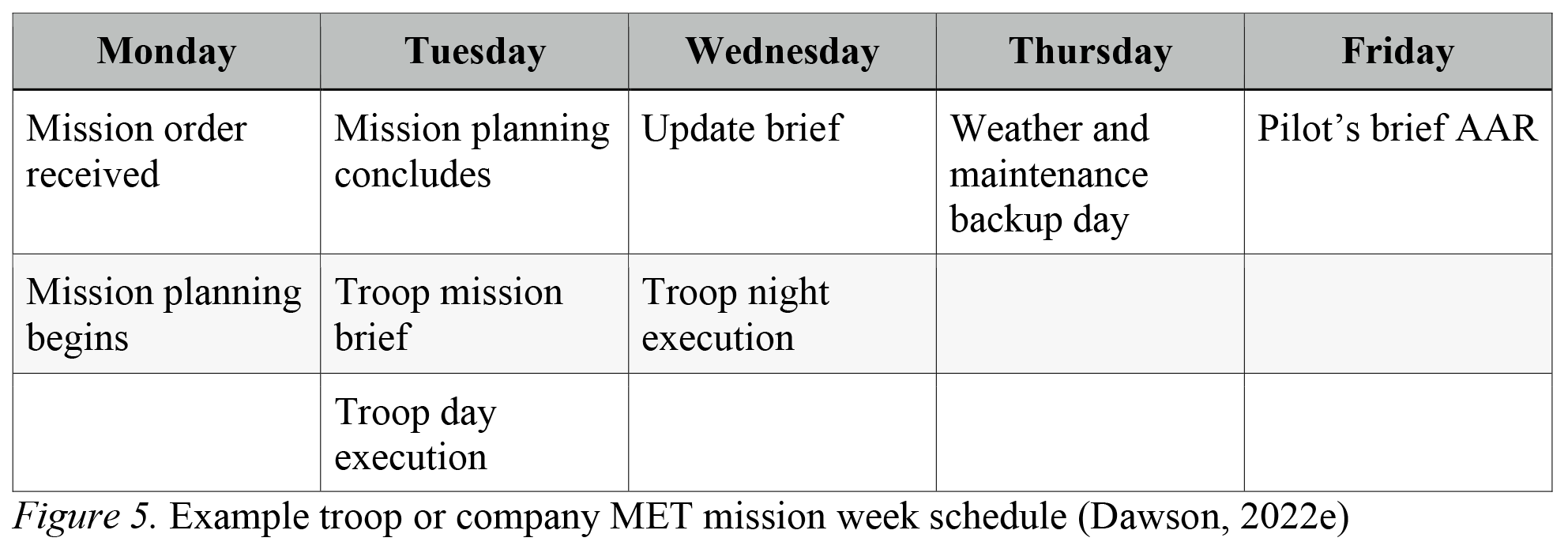

Figure 4. Example troop or company MET mission week schedule (Dawson, 2022e).

On Monday, the PLs, serving as the air mission commander (AMC), receive the mission order, lead planning cells, and conduct a mission brief on the day of execution. After the brief, the mission is executed twice per platoon. The first during the day and the second at night. The first iteration serves as a dry run to mitigate risk, while the second increases the complexity of the operational environment potentially culminating in a “T” (fully trained) level of proficiency. In between each iteration, time is allotted for a hot wash3 for the AMC, pilots, and external evaluator to quickly debrief any key sticking points or safety concerns prior to execution at night. To conclude the week, Thursday is a weather and maintenance backup day, and during Friday's troop pilot's brief, a formal after-action review (AAR) can take place.

Troop echelon execution functions primarily the same except the troop commander serves as the AMC. Additional time is allocated for planning and mission completion due to the increased complexity and risk associated with additional aircraft (Figure 5).

This begs the question; from where does a troop or company commander receive an operations order (OPORD) with supporting annexes and appendices? If coordinated in advance, the S3 and S2 could provide the needed products, or they can be created internally. For most units, a quick search of the shared drive will yield previous OPORDs and supporting products that can easily be adapted to meet the needs of the unit. Products such as an information collection matrix and fires support execution matrix add increased realism, while enabling aviators in the various mission planning cells to hone their skills. This ensures the scenario used requires aviators to practice the ITs and SCTs covered during the month's training flights.

Opposition forces (OPFOR) can be sourced from within. For example, during a training mission, crew chiefs with light medium tactical vehicles and high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles can be used to simulate enemy convoys, tanks, or other vehicles. The intent is not to spend egregious amounts of time building OPORDS and coordinating OPFOR but to provide what is necessary to facilitate the training.

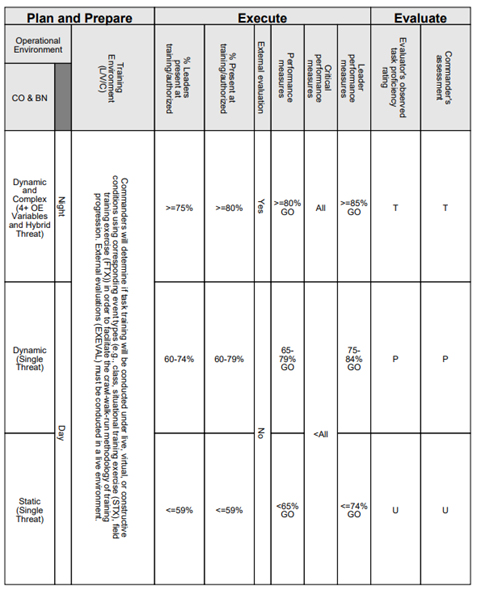

At the conclusion of training, has the unit objectively and completely met the criteria to achieve a T rating using the task evaluation criteria matrix (Figure 6)? If not, has additional time been included on the calendar for retraining? Leaders demonstrate their commitment to training to standard and not to time by including time for retraining and additional repetitions as needed on the calendar. Not attaining a specific rating doesn’t mean failure; that is what training is for, making mistakes and learning from them. It enables leaders to “drill down” and determine the specific tasks requiring additional attention.

For units who do attain a T rating on their first attempt, it isn’t a one-and-done process. Proficiency is something that must be maintained over time. A good training plan should be easily repeated, ensuring the unit has multiple attempts to sustain their expertise. Put simply, for aviators to remember how to plan and execute a certain mission, they require meaningful repetition. After proficiency is achieved, leaders should change the scenario to keep the training fresh and interesting, while providing additional tactical challenges for the unit to overcome. This enables leaders to continually evaluate their unit’s proficiency level objectively and completely. However, this does not mean units will be able to attain a T on all METs. In fact, FM 7-0 allows for this by emphasizing that “units are rarely able to achieve and sustain fully trained proficiency on all METs simultaneously” (DA, 2021, p. 2-1). In Figure 1, all METs are listed, not to infer the organization has achieved a T on every MET, but rather for presentation purposes. If a unit requires it, the same MET could be trained multiple months in a row. Prioritization remains paramount to planning and executing a successful training strategy.

Linking Aviation Training to Mastering the Fundamentals

How does aviation training, which results in achieving and sustaining a T rating on a MET, relate to mastery of the fundamentals? Proficiency, and subsequently a T rating, must be built from the individual level up. The ITs and SCTs trained during weekly training flights are selected from the TE&O of the month’s MET focus and correlate to the fundamentals listed in FM 7-0. A review of the ATM will show the majority of tasks revolve around the fundamentals of shooting, moving, communicating and surviving, regardless of airframe. For example: Engage Target with Area Weapon System (shoot), Perform Terrain Flight (move), Perform Digital Communications (communicate), and Operate Aircraft Survivability Equipment (survive).

Figure 6. Task evaluation criteria matrix (Army Training Network, 2022).

Consider the Integrate Survivability Measures Into Aviation Missions task, an SCT for the reconnaissance MET. Upon reviewing the Integrate task, one will find Operate Aircraft Survivability Equipment (ASE) listed as a supporting individual task. As noted earlier, Operate ASE is an individual task found in the ATM. This is just one simple example demonstrating the relationship between an IT, SCT, and MET.

Fighting for White Space

This method is not a one size fits all and will not always work exactly as explained here due to other requirements. In practice, not every month will be a perfect 4-week cycle with 3 weeks of training flights and 1 week for mission execution. Changes may have to be made based on the proficiency of the organization or possibly prioritization of other training requirements. To minimize the disruption to training, it is imperative to engage early and often with the S3 and ensure adequate time is allotted for troop-level training. In other words, fight for every day of white space on the calendar. For example, if the next higher headquarters is planning a field problem, such as a pre-CTC validation, ensure your training requirements are included. Request an OPORD assigning a platoon, company, or troop mission based on the month’s MET focus. For METs with a live-fire component, such as Movement to Contact, try to align these with gunnery or other live-fire events. As challenging as it may be, staying ahead of the S3 and commander will make it more likely company or troop training events are supported.

Final Thoughts

In closing, it is important to note the ideas above simply represent a way and are not the way to train. Every team is different and will require its commander to be familiar with the intricacies of the unit they command. Striking a balance between training the organization and burning people out is paramount. Push too hard and resentment will fester, push too little and skills will atrophy, increasing risk. Ultimately, stick to the following principles and they will help you succeed:

- Do not be the officer who chides others for flying. Make flying a priority. Technical and tactical proficiency saveslives

- Set the standard by traininghard

- Create buy-in and give othersownership

The ideas presented in this article are not solely the creation of the author. They are the result of collective efforts from multiple leaders across the 82D Combat Aviation Brigade including the 1st Squadron (Air Cavalry), 17th Cavalry Regiment, and the 1st Battalion (Attack), 82D Aviation Regiment. Together, we crafted a coherent training strategy by understanding what we were asking of our teams—mastery of the fundamentals. The basics of shoot, move, communicate, and survive are not unique to Army Aviation and are embedded in nearly every task in the ATMs. After achieving an understanding of a unit’s capabilities, missions, and METs, commanders should work with other key leaders to craft a simple training plan. The plan should start at the individual level, with carefully selected individual and supporting collective tasks, before culminating in a platoon and subsequently, a troop or company mission. Success is paramount to maintaining a competitive edge.

The 50th Expeditionary Signal Battalion (Enhanced) and 63D Expeditionary Signal Battalion conduct a large-scale combat operations communications exercise. U.S. Army photo by CPT Eric Messmer.

References

Army Training Network. (2022, March 8). Conduct expeditionary deployment operations. Department of the Army. https://atn.army.mil/ATNPortalUI/METL/

Dawson, T.R. (2022a). Example of a training strategy summary.

Dawson, T.R. (2022b). Example of a monthly training calendar.

Dawson, T.R. (2022c). Example training flight kneeboard.

Dawson, T.R. (2022d). Example platoon MET mission week schedule.

Dawson, T.R. (2022e). Example troop or company MET mission week schedule.

Department of the Army. (2020, April). Army aviation (Field Manual 3-04). https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN21797_FM_3-04_FINAL_WEB_wfix.pdf

Department of the Army. (2021, June 14). Training (Field Manual 7-0). https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN35076-FM_7-0-000-WEB-1.pdf

Department of the Army. (2022, October 1). Operations (Field Manual 3-0). https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN36290-FM_3-0-000-WEB-2.pdf

Doran, G. T. (1981, November). There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Journal of Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

Footnotes

2. The ATN is available via the Enterprise Access Management System-Army to those with a valid common access card.

3. Hot wash is jargon for a brief AAR or review while an exercise is ongoing and is meant to be followed up with a full AAR after the event concludes.

Author

CPT Ty R. Dawson is an AH-64E IP assigned to Company A, 1st Battalion, 14th Aviation Regiment, at Fort Novosel, Alabama. He previously served as the commander of B/1- 17th and D/3-82, at Fort Bragg (Liberty), North Carolina, and deployed to Afghanistan in 2021.