On the Wings of Destiny

Promoting Cooperative Training Between Military Intelligence and Military Police

By By 1LT Charlie O'Brien, MAJ Ronald Braasch, MAJ Sean Boniface, and COL Clinton Cody

Article published on: April 1, in the Army Digest April-June 2024 edition

Read Time: < 17 mins

On the evening of January 13, 2024, the skies of Fort Johnson, Louisiana, erupted as 16 AH-64 Apache helicopters

from 2D Squadron-17th Cavalry Regiment (2-17th) “Out Front” conducted a live-fire exercise on a

templated enemy position located on Peason Ridge. This out-of-contact spoiling attack, which launched from Fort

Campbell, Kentucky, initiated the largest and most overwhelming rotary-wing training operation in recent

history. Moments later, 16x CH-47 Chinooks and 22x UH-60 Black Hawks delivered 481 Soldiers, 20 Infantry Squad

Vehicles (ISVs), and five M119 howitzers from the 101st Airborne Division’s 2D Brigade Combat Team (2BCT),

“Strike.” Four helicopter landing zones (HLZs) swarmed with Strike Soldiers secured by 10 Apaches

from the 1st Battalion, 101st Aviation Regiment (101st) “No Mercy.” In one period of darkness (POD),

the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB) “Wings of Destiny,” launched 76 aircraft executing 743

flight hours and covering 500 nautical miles (nm), allowing Strike to seize a lodgment against the tenacious and

well-trained Geronimo forces of the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC). Over the next 36 hours, the CAB air

assaulted additional combat power from an intermediate staging base (ISB) amassing 838 Soldiers, 72 ISVs, 28

High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles, five M119 howitzers, and 23 other vehicles/trailers, totaling 128

pieces of equipment delivered. The successful execution of Eagle Eclipse was built upon a well-developed road to

war and “left of crank” preparations prior to the mission. Moreover, it required innovative

sustainment and mission command programs. This large-scale long-range air assault (L2A2) 1 and synchronized out-of-contact attack on key enemy

assets ensured the success of Operation Eagle Eclipse and proved the “Wings of Destiny” Brigade is

in a unique position to continue pushing the envelope for Army Aviation in the only Air Assault Division

(Worley, 2024).

Figure 1. Task organization for Operation Eagle Eclipse (101st Airborne G5

shop—edited by the 101st CAB).

Execution of Eagle Eclipse

Operation Eagle Eclipse was an L2A2 from Fort Campbell to the training area at Fort Johnson. MG Sylvia, the

Division Commander, was the Air Assault Task Force Commander. COL Stultz, the 2BCT Commander, was the Ground

Force Commander, and COL Cody was the Aviation Task Force Commander (Figure 1).

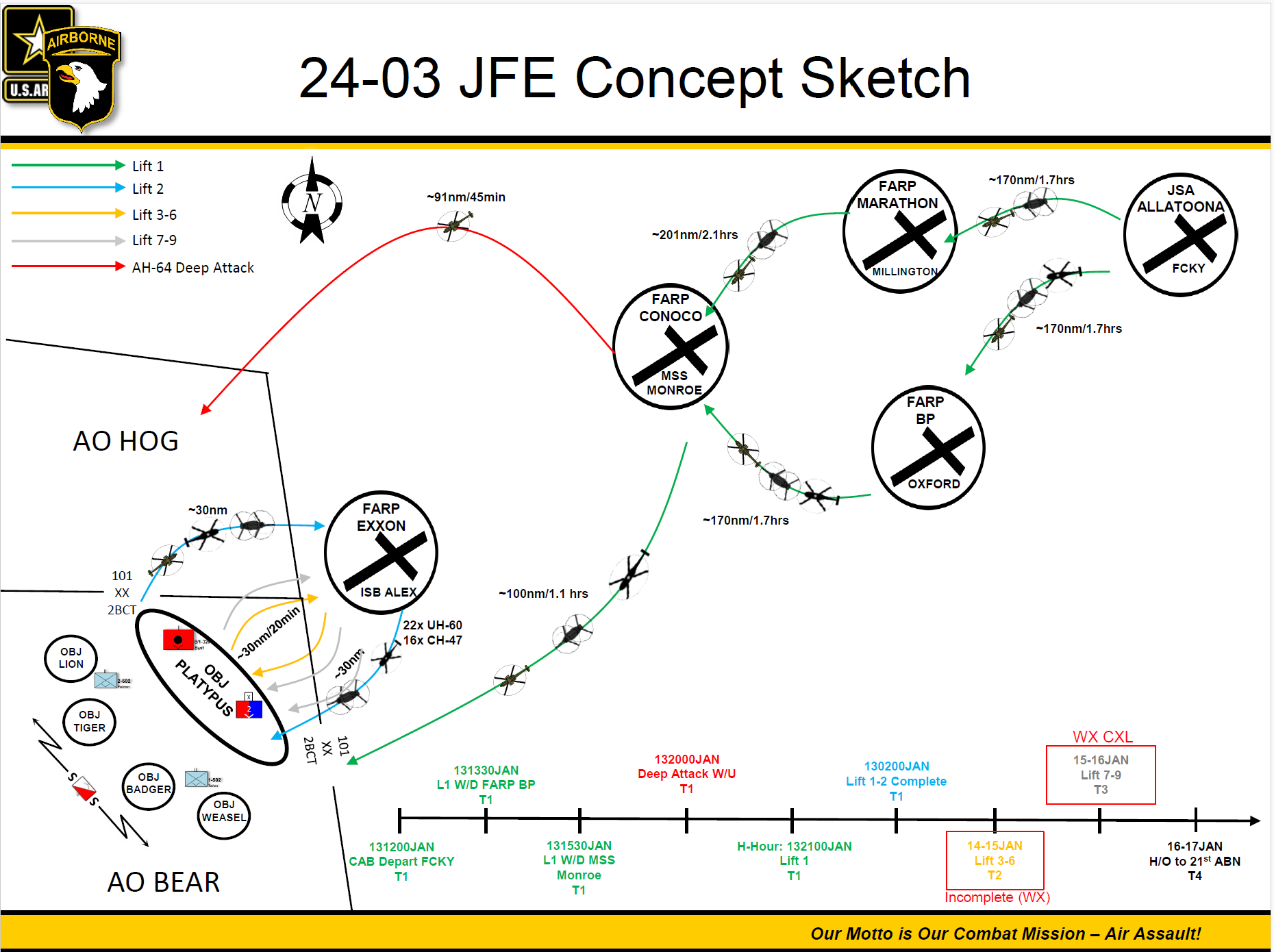

The operation required four forward sustainment nodes: the forward arming and refueling point (FARP) Marathon in

Millington, Tennessee; FARP British Petroleum (BP) in Oxford, Mississippi; mission support site (MSS) Monroe in

Monroe, Louisiana; and ISB Alexandria in Alexandria, Louisiana, which contained three separate FARP sites

(Figure 2).

Figure 2. Concept of Operation Eagle Eclipse (101st Airborne G5 shop—edited by the

101st CAB).

The operation began with a spoiling attack of 16 AH-64s from the 2-17th. The 2-17th was tasked to conduct an

attack against enemy forces out of close friendly contact, in order to set conditions for the air assault.

Through high confidence intelligence, detailed fuel planning, and thorough engagement area (EA) development, the

2-17th’s movement and subsequent actions on the objective were swift and decisive, allowing for the air

assault to continue on time. The phased attack employed four platoons consisting of four AH-64s each. The 2-17th

staggered the departure of each platoon from Sabre Army Airfield, Fort Campbell, armed and refueled at Monroe,

and serviced the EA located on Peason Ridge to ensure continuous fires on the objective. Through battle

handovers and cumulative battle damage assessment,the 2-17th verified the destruction of a mechanized

reconnaissance unit north of the HLZs, clearing the way for the assault force.

While the attack was underway, eight lifts took off in 30-minute intervals, refueling at the FARP’s BP or

Marathon before continuing to MSS Monroe. At Monroe, crews refueled and received an operations and intelligence

(O&I) update, then flew to one of four HLZs under the security of AH-64s from “No Mercy.”

Following this initial lift, the aircraft flew to ISB Alexandria to refuel, picked up more Soldiers and

equipment, and completed a second lift. The following night, lifts were launched from ISB Alexandria to

reinforce the lodgment and complete L2A2 operations for Eagle Eclipse.

Figure 3. 101st CAB's L2A2 road to war for Operation Eagle Eclipse (101st

CAB—edited by the 101st Airborne G5 shop).

Scaling up and out: 101 CAB’s Road to war

Operation Eagle Eclipse’s scale (in fleet size and distance flown) resulted from a deliberate road to war

undertaken by the 101st CAB and the division (Figure 3). In September 2022, the CAB executed Operation Lethal

Shadow, a proof-of-concept long-range air assault with 23 aircraft from Fort Campbell to Fort Johnson. Four

months later, the brigade validated extended-range fuel systems over a 340-nm mission to Florida with the 75th

Ranger Regiment. In February 2023, Operation Ultimate Destiny launched a 32-aircraft air assault (56, including

attack and medical evacuation support) from Fort Campbell to Fort Knox, Kentucky, while maintaining aerial

command and control (C2). Destiny also employed 2 eight-point FARPs, 1 four-point FARP, and 2 CH-47 Fat Cows

(used to refuel other aircraft) at an expeditionary sustainment node at Wendell H. Ford Training Center

(Kentucky). The following month, an exercise known as Driving Innovation in Realistic Training (DIRT) Days 2 stressed the CAB’s

sustainment capacity at range, fueling aircraft at FARPs dispersed across four states to exfil Soldiers from

Fola, West Virginia.

Following DIRT Days, the division took lead as the unit of action and in August 2023, executed a 150-nm air

assault during Operation Lethal Eagle (OLE) III. This operation validated an island-hopping scenario and

synchronized CAB and division planners during simulated joint-fires exercises. Immediately following OLE III,

the division enabled Task Force Shadow, led by the 6th Battalion, 101st Aviation Regiment (6th-101st), to

execute a joint forcible entry exercise for JRTC 23-10. While smaller in scale than Eagle Eclipse, the CAB

sustained the operation without drawing fuel from civilian airports. This final exercise validated that the CAB

could C2 an L2A2 and sustain it with organic assets, setting conditions for Eagle Eclipse.

Destiny fleet at ISB Alexandria prior to the second mission night. Photo by CPT Austin Lachance.

“Left of Crank” Preparations Can be the Difference Between Mission Success or

Failure

For Army Aviators, “left of crank” means completing mission planning and rehearsals, finalizing

maintenance, and identifying and mitigating risk to ensure a successful operation. Destiny employed centralized

planning, a surge maintenance program, and an innovative approach to risk mitigation to accomplish the division

commander’s training objectives.

Critical to Eagle Eclipse’s success was dedicated planning at the brigade level. MAJ Boniface empowered a

CAB flight lead and flight packet “czar” to ensure deliberate planning occurred with the right

subject matter experts and employed a single digital mission packet for the operation. This

product—hot-linked to every required document, including performance planning cards, airfield diagrams,

and frequency cards—was crucial in ensuring flight crews could easily access information during mission

execution.

Well-planned rehearsals also helped ensure success, despite the planning window ending at holiday block leave.

Though Destiny returned on January 3 (just 8 calendar days before execution), the CAB’s detailed

plan-to-plan forecasted time for battalion and air mission commander (AMC) rehearsals. Destiny executed an

aviation task force rehearsal (AVN TF RXL) on January 8, followed by a division combined arms rehearsal (CAR)

the next day, enabling 2 days for lift and attack battalion-level rehearsals.

Executing rehearsals for missions at this scale underscored the friction between the ground and aviation forces.

The CAR terrain model emphasized actions on the objective, yet the AVN TF RXL focused on high-volume air traffic

areas, including sustainment nodes and attack aviation EAs. By participating in the CAR, aircrews refined HLZs

and EAs for the ground and aviation forces. Moreover, the CAB’s sync matrix-driven AVN TF RXL discovered

errors in the execution checklist. Ultimately, the CAB’s rehearsal was early enough, and the terrain model

detailed enough, to enable battalion and aircrew rehearsals.

Aircraft maintenance for an L2A2 requires a deliberate readiness build-up. The measure of effectiveness for scale

and range in an L2A2 is the number of aircraft required and the number of maintenance hours available. For a

mission of the scale of Eagle Eclipse, the CAB’s commanders at echelon directed a maintenance surge, which

shifted unit efforts from flight operations to maintenance. For example, the 6th-101st maintenance team

minimized flights before mission night, sequenced flight-hour inspections, and pre-positioned assets to sustain

multiple lifts and mission nights.

Minimizing flights before the mission reduced the risk of unscheduled maintenance, postured the fleet for

follow-on operations, and ensured crew chiefs could focus on maintenance tasks. For Operation Eagle Eclipse, the

CAB reduced flying hours 45 days before execution. This tactic took advantage of the holidays but ensured 17

CH-47s and 22 UH-60s launched on mission night 1. Protecting maintenance by reducing flight hours before an L2A2

will be challenging but is necessary to build the required combat power. The more rotary-wing aircraft fly, the

more likely there will be unscheduled maintenance, which could limit aircraft availability. Commanders must also

balance assets for future operations. In a single L2A2 mission night, a company expended about 10 percent of the

hours of a phase maintenance inspection, reducing the unit’s ability to project combat power over 14 days.

Minimizing flights can ensure the unit is postured to continue operations following an L2A2.

Sequencing flight hours and interval inspections—the art and science at the heart of aviation

management—was also useful. Technical Manual (TM), 1-1500-328-23, “Aeronautical Equipment

Maintenance Management Procedures,” for example, lays out the science (and regulatory guidance) of how to

execute these procedures (Department of the Army, 2014). The art comes from maintenance managers who

operationalize inspection intervals to maximize flight hour duration. During Eagle Eclipse, production control

teams coordinated and aligned maintenance actions and priorities 45 days from mission execution. This effort

made it feasible to order and install parts, resulting from common inspections that historically incur downtime,

well in advance. The 6th-101st, for example, executed six CH-47 160-hour inspections in the 45-day window before

the mission. This sequencing allowed maneuver companies to minimize flight hour limitations and maximize the

range capability during the L2A2.

Pre-positioning maintenance assets at key logistical hubs allowed the CAB to execute contingency and planned

maintenance and should not be overlooked for future L2A2 operations. At Monroe, maintenance teams from the 96th

Aviation Support Battalion (ASB) repaired the CAB’s 17th Chinook and returned it to the fight during

mission night 1. Moreover, SGT Day’s team at Alexandria completed four UH-60 torque checks following that

evening’s lifts, ensuring these Black Hawks would be ready for mission night 2. Aircraft require an

exorbitant amount of support equipment and Class IX (repair) parts, and positioning these assets at established

FARP sites was critical for the success of Eagle Eclipse.

Capturing and mitigating operational risk was also central to planning for Eagle Eclipse. Combat aviation brigade

planners recognized that 7 hours of flight within a 12-hour duty day would not meet the brigade’s

obligations to the ground force. The brigade standardization team, led by CW5 Trail, CW4 Koeppen, and SFC

Gravitt, developed an adjustment to the aviation standard operating procedure, signed by COL Cody. 3 This adjustment extended the

aviation duty day to 14 hours and authorized 9 hours of day flight, 8 hours of combination flight, and 7 hours

of night vision device flight for each day of the mission. To mitigate the increased risk, COL Cody met with

AMCs and missions briefing officers and approved risk assessments at his level. He dictated that crew members

who exceed 28 hours in duty day or 16 hours of flight time became “high risk” until they could take

a 24-hour reset. Crew members who received extensions on both mission nights would be designated

“extreme-high risk” until they executed a 24-hour reset.

The brigade standardization team also sought to codify tactics, techniques, and procedures for unique loads to

manage risk, as sling load publications (with lists of standardized loads) have yet to keep pace with new

equipment fielding. The manuals for helicopter sling loads (TM 4-48.09, TM 46-48.10, and TM 4-48.11), for

example, are all over a decade old. This delay places the onus for rigging procedures on CABs, increasing risk.

Figure 4. Example RPC showing two “Shot Gunned” ISVs (101st CAB

Standardization Shop).

To standardize these unique loads, COL Cody signed Aviation Standardization Bulletin 23-04, which delegated the

approval for unique slings loads with external load rigging procedure cards (RPCs) to a moderate risk approval

authority. MG Sylvia further approved a memorandum dated January 5, 2024, assessing seven unique loads,

including ISVs in various configurations, as low risk. These loads have RPCs, which include required materials,

preparation, rigging steps, and common deficiencies (Figure 4). Approved less than 2 weeks before Eagle Eclipse,

this memorandum’s delegation of risk approval streamlined mission preparation and execution.

In addition to standardizing external load procedures and risk approval, the brigade developed loading plans for

dual-ISV internal loads (Figure 5). After multiple frustrated loads during the division’s Operation

Destiny Phoenix (2 months before Eagle Eclipse), CH-47 crews from the 6th-101st worked with partners in 2BCT to

develop and rehearse a dual-ISV load that maximized ease of loading, safety, and cargo space. Further refined

with comments following Eagle Eclipse, this standardized load procedure is set to serve the division for future

L2A2s.

Figure 5. Proposed dual-ISV internal load diagram (modified slightly from the format

used during Eagle Eclipse) based on after-action review comments from aircrews and the ground force (6th-101st

General Support Aviation Battalion shop).

Sustainment at Scale

Redundant sustainment defined Eagle Eclipse. At Sabre and Campbell Army Airfields, dedicated launch teams (with

maintenance, refuel, and communications packages) stood by for support. On launch, aircraft flew to the

FARP’s BP or Marathon but could divert if either were fouled. The FARP BP, run by the ASB, was a 12-point

FARP; whereas, the Marathon was airmobile, led by the 6th-101st Forward Support Company (FSC). The FSC loaded

two Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Trucks (HEMTTs), two 250 gallon-per-minute pumps, three 3,000-gallon fuel

bags, and a tactical aviation ground refueling system into a C-17 at Fort Campbell 2 days before mission

execution and flew them to Millington. After unloading, the C-17 fueled the HEMTTs to establish a six-point

FARP.

MG Brett Sylvia, Commanding General of the 101st Airborne Division, gives his opening remarks

during the Division Combined Arms Rehearsal. Photo by CPT Austin Lachance.

Whether taking off from the FARP’s BP or Marathon or bypassing these sites for MSS Monroe, all aircraft

stopped in Monroe. Monroe issued 149,000 gallons of fuel using 18 HEMTTs and two Tactical Refueling Tank Rack

Modules (TRMs) with separate refuel teams for each airframe. UH-60 and CH-47 ramps facilitated space for

aircraft bumps, and the 28 AH-64s parked near their own FARP for live arming. Prepared at each ramp was a

maintenance contact team and Downed Aircraft Recovery Team (DART) with a UH-60 on standby to assess aircraft

requiring maintenance en route from Fort Campbell. Aircrews received tailored O&I briefs over Android Team

Assault Kits for Military (ATAK-MIL), and battalion commanders traveled to the brigade tactical operations

center (TOC) for in-person mission updates.

The forwardmost sustainment node at ISB Alexandria serviced aircraft with 3 four-point FARPs. Two pickup zones

(PZs) for lifts two through nine were co-located at Alexandria Airport. The FARP Exxon employed 16 HEMTTs and

six TRMs. The brigade main command post provided C2, while Company Fox, 6th-101st, coordinated air traffic.

Finally, dedicated maintenance personnel worked overnight maintenance and launch support for mission night 2 and

redeployment.

In an Aviation Digest article on aviation sustainment in Large-Scale Combat, the author noted that

“logistics will be the key component for success in aviation operations” (Glover, 2024, p. 15).

Eagle Eclipse proves this point. For subsequent iterations of L2A2s, resupplying sustainment nodes and

protecting these critical pacing items must drive greater integration with air defense and joint assets. While

the CAB’s footprint collapsed to Alexandria for enduring operations, it is foreseeable that the mission

could require dispersed sustainment nodes for extended periods to reinforce the lodgment and secure lines of

supply and communication for follow-on operations. These considerations will be tested in future iterations at

Fort Campbell, where the division will execute another L2A2 and continually support Soldiers on the ground via

heliborne resupply and fires.

Mission Command and C2 inLSCO

Eagle Eclipse’s scale required the division to define who owned which fights. The CAB empowered leaders at

various locations to do the same. In the air, command relationships were straightforward, an anomaly for a

brigade shaking off the multifunctional aviation task force (MFATF) mentality of recent deployments. Troop and

company commanders were lift-or-attack weapons team AMCs, and flight battalion commanders served as AMCs for

their units. To maintain a common operating picture for this dislocated force, the AMC's primary method of

over-the-horizon digital traffic was the ATAK-MIL, which allowed immediate situational awareness and digital

O&I updates.

Combat aviation brigade personnel at five ground nodes fell under an officer-in-charge (OIC), who tracked mission

progress and directed maintenance, refueling, and contingencies during the operation. The brigade executive and

operations officers oversaw the CAB’s two critical nodes at Monroe and Alexandria. As the aircraft

departed from home station, AMCs reported to the brigade operations cell at Fort Campbell. After the aircraft

passed Oxford or Millington, the TAC at Monroe assumed control of the fight and tracked aircraft until they

departed for the objective. Once clear of Monroe's airspace, the main command post at Alexandria owned the

fight for the mission's duration.

Destiny synchronized its efforts with the division support brigade (DSB), which tracked and reported node

statuses. When diversions due to weather resulted in unanticipated fuel requirements, the DSB (whose command

post was collocated with the TAC) linked in with the CAB’s Assistant Operations Officers (AS3s), node

OICs, and support operations officer cell to assess mission impacts. Aircraft maintenance concerns were reported

to MAJ Haynes, the Company Bravo 96th ASB Commander and DART OIC, who owned sourcing the appropriate maintenance

solution.

Ultimately, the CAB's employment of battalion field-grade leaders, especially in the “push

package” at Fort Campbell and augmentation at Monroe, enabled mission command and streamlined C2. Combat

aviation brigades executing similar operations in the future should note this technique.

Crew chief from 6th-101st GSAB supervises the loading of a second ISV into a CH-47 at Campbell

Army Airfield. Photo by CPT Austin Lachance.

Conclusion: L2A2s and the Future Fight

In his opening remarks of the 2023 revised 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) Gold Book, MG Sylvia stated that

the division’s goal was to “fly 500 nautical miles in one POD, in any environment to endure for 14+

days and win.” Operation Eagle Eclipse highlighted how far we have come, flying 500 nm and moving a

battalion-plus-sized force onto the objective. We captured incredible data from this operation, and after-action

reviews highlighted friction, generated solutions, and inspired future training.

Some of the lessons the CAB learned were critical. Aerial C2 at the brigade level for an L2A2, for instance,

cannot be overstated. In smaller air assaults, the MFATF commander might lead as an AMC with one of their

field-grade leaders in support. It was apparent to those who participated in Eagle Eclipse that the operation

needed multiple aerial C2 nodes fed through voice and digital communications from AMCs and command posts.

Dispersed sustainment nodes must also include a diverse resupply plan. Like a Primary, Alternate, Contingency,

Emergency, (PACE), plan with four distinct communication systems or frequencies, four or more FARPs will require

innovative methods to maintain. Training airmobile FARPs gave the 6th-101st’s FSC firsthand experience

with joint refuel capabilities they will likely see in an island-hopping fight. Limitations previously not

considered, such as wet wing refuel (wing structure is sealed and used as a fuel tank) rates, are now codified

into Destiny’s sustainment procedures.

The future of L2A2 operations is the future of LSCO for Army Aviation. The missions executed during Operation

Desert Storm and the opening days of Iraqi Freedom can serve as a guide. Yet, air assaults of the scope and

scale of an L2A2 require deliberate attention from leaders experienced in operations like Eagle Eclipse. For

L2A2s to be a suitable, acceptable, or preferred option for combatant commanders seeking a lodgment, Army

Aviation owes the ground force, Army leadership, and aircrews particular emphasis in future training. We must

train like we fight—flying lower, at night, in formation—and with covert lighting (an acknowledged

challenge in the contiguous United States). We must also innovate our Sustainment Enterprise, so our long-range

ambitions do not rapidly outpace our refuel and rearm capabilities. Fuel is the lifeblood of a CAB, and leaders

must emphasize the modularity, survivability, and adaptability of our sustainment nodes. Finally, we must drive

doctrine that will outlive the aircraft for which it was created. Eagle Eclipse has set conditions for the

future of L2A2 operations, and the Wings of Destiny team is ready to answer the call.

The authors would like to thank CPT Richard Fischl for his input on surge maintenance and all the

Soldiers and families of the 101st CAB who made Operation Eagle Eclipse a success.

References

Department of the Army. (2014, June 30). Aeronautical equipment maintenance management procedures.

(Technical Manual 1-1500-328-23). https://armypubs.army.mil/ProductMaps/PubForm/Details_Printer.aspx?PUB_ID=52437

Glover, L. K. (2024, January-March). Aviation sustainment in large-scale combat. Aviation Digest,

12(1), 15.

Steelhammer, R. (2023, May 7). Soldiers field-test technology, innovation at West Virginia mine. Army

Times. https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2023/05/07/soldiers-field-test-technology-innovation-at-west-virginia-mine/

Worley, D. (2024, January 25). 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) conducts long-range, large-scale air

assault. U.S. Army. https://www.army.mil/article/273195/101st_airborne_division_air_assault_conducts_long_range_large_scale_air_assaultmentions

Footnotes

1. L2A2 is an evolving method of employing AASLT that is not yet

codified in doctrine.

2. DIRT Days is an “event aimed to involve Soldiers in developing

and field-testing new tactics and technology while taking part in challenging, realistic training

exercises” (Steelhammer, 2023).

3. The aviation standard operating procedure, Aviation Standardization

Bulletin (23-04), memorandum dated 5 January 2024, and revised 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault)

Gold Book, may all be obtained by contacting the 101st CAB.

Authors

1LT Charlie O’Brien is an Assistant Operations Officer in 101st CAB and an AH-64E pilot-incommand

(PC).

MAJ Ronald Braasch is the Battalion Operations Officer for the 6th-101st. He has a Ph.D. in History from

Fordham University and is a CH-47F Standardization Instructor Pilot.

MAJ Sean Boniface is the Brigade Operations Officer for the 101st CAB and an AH-64E PC/AMC. During Eagle

Eclipse, MAJ Boniface controlled the 101st CAB TAC for this Operation at Monroe, Mississippi.

COL Clinton Cody is the Brigade Commander for the 101st CAB and was the Aviation Task Force Commander for

Eagle Eclipse.