Countering Lawfare of the People’s Republic of China Starts with “PRC,” Not “China”

By Lieutenant Colonel Richard J. Connaroe II

Article published on: January 1, 2024 in the Army Lawyer issue 2 2024 Edition

Read Time: < 14 mins

The USS Chung-Hoon observes People’s Liberation Army (Navy) LUYANG III DDG 132 execute unsafe

maneuvers while conducting a routine south-to-north Taiwan Strait transit alongside the HMCS Montreal on 3 June

2023. (Credit: MC1 Andre T. Richard, U.S. Navy)

Every time an American or a potential partner nation refers to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as “China,”

the PRC is winning strategic legal warfare—or lawfare.1 Every quip and offhand reference about “China” unwittingly yields to PRC

lawfare tactics and furthers the PRC’s agenda. Not only do we legitimize the PRC’s “One-China Principle,”2 but we also delegitimize strategic

ambiguity while we otherwise strive to compete internationally.3 We are helping the PRC to win.

This article explains how commanders, Service members, citizens of the United States, and partner nations

everywhere can counter PRC lawfare by using proper terminology. First, this article introduces the concept of

lawfare. It then provides a common scenario of lawfare in action. Critical to understanding the scope of PRC

lawfare is the historical context of the word “China,” which is at the heart of one of PRC’s most prevalent

lawfare tactics. After understanding the PRC’s method and scope of its lawfare, this article describes how

properly referring to the PRC as “the PRC,” not as “China,” is essential to countering PRC lawfare.

What Exactly Is Lawfare?4

While not explicitly defined in Department of Defense doctrine, lawfare is commonly defined as the use of the law

to achieve a policy objective.5

Academics postulate overlapping types of lawfare.6 First, “battlefield exploitation lawfare is the exploitation of an

adversary’s law-abidingness.”7

Second, instrumental lawfare is the use of legal tools, like sanctions or bans, to achieve effects similar to

conventional military actions.8

Third, proxy lawfare is legal action against an adversary’s proxy, such as a PRC or Russian corporation.9 Fourth, “information lawfare is the

use of law to control the narrative” of competition or conflict or the use of misleading legal positions to

justify coercion or aggression.10

Fifth, institutional lawfare is the creation of domestic law to achieve strategic efforts, such as asserting

sovereignty or jurisdiction.11 The

PRC, however, has clearly defined lawfare.12

The PRC has implemented three reinforcing warfares: legal warfare, public opinion warfare, and psychological

warfare.13 The PRC views lawfare

as an offensive weapon to seize the initiative—a form of combat.14 The PRC lawfare involves “arguing that one’s own side is obeying the

law, criticizing the other side for violating the law, and making arguments for one’s own side in cases where

there are also violations of the law.”15 Conversely, public opinion warfare is the struggle over media dominance,

and psychological warfare involves erosion of political will.16

As demonstrated in the commonplace example below, lawfare is part of the PRC’s daily operations, which

necessitates U.S. counter-lawfare—activities that preserve legitimacy, build legal consensus, and oppose

unlawful action and misinformation that threatens the rules-based international order.17 The PRC regularly shadows and confronts vessels

in the South China Sea18 because

the PRC asserts sovereignty over it.19 Nearly one-third of global maritime trade—or $5.3 trillion of

trade—passes through these waters each year, and the PRC portrays U.S. navigation in these waters as a violation

of international law.20 Throughout

these engagements, the PRC asserts that it is obeying—even enforcing— the law and the United States is

aggressively violating the law, specifically PRC sovereignty, even when the PRC is operating its own vessels in

an unsafe manner.

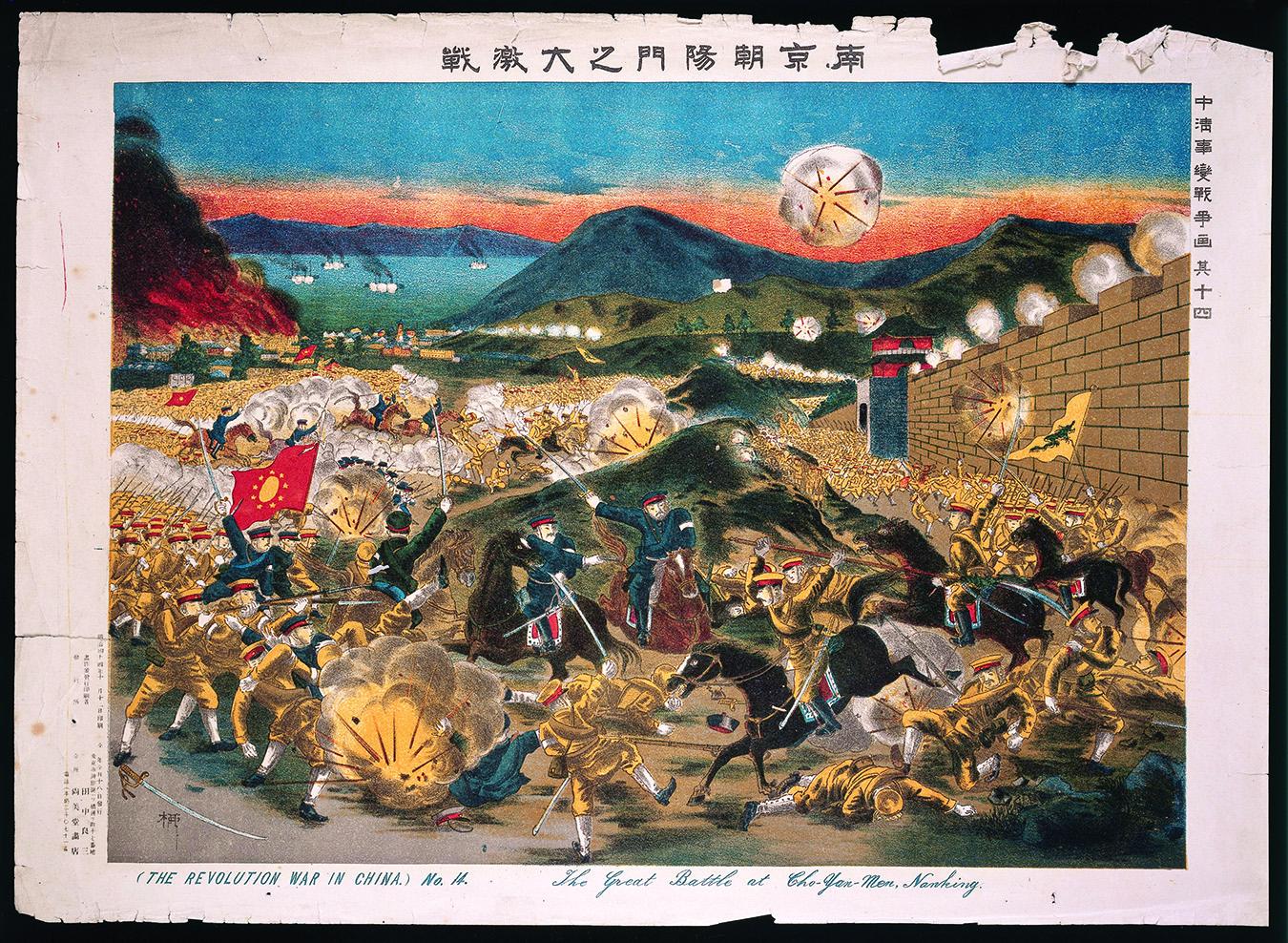

The battle at Cho-Yan-Men, Nanking, in the Revolution of 1911. (Credit: T. Myano, Wellcome

Collection)

“Haven’t We Had this Conversation Before?”21

PRC: “U.S. Navy Warship eight nautical miles off my starboard beam, this is PRC22 Warship. You are approaching

[indiscernible] Reef and Chinese sovereign waters. Remain clear of our contiguous zone. Please alter course and

leave immediately"

Aboard the U.S. ship, the junior officer of the watch (JOOW) picks up the bridge-to-bridge radio, sighs, and

responds

U.S. Navy: “PRC Warship, this is U.S. Navy Warship. I am a sovereign, immune U.S.

Navy vessel conducting lawful military operations beyond the territorial seas of any coastal state. In

exercising my rights as guaranteed by international law, I am operating with due regard for the rights and

duties of all states.”

As the U.S. Navy ship continues through international waters, transiting through the Luzon Strait and into the

South China Sea, the JOOW knows this will be a continuous, repetitive back and forth with the PRC vessel.

PRC: “U.S. Navy Warship, this is PRC Warship. You are in Chinese sovereign waters.

Please alter course and leave immediately.”

U.S. Navy: “PRC Warship, this is U.S. Navy Warship. I am a sovereign, immune U.S.

Navy vessel. I will not respond again to this incorrect assertion. Request you keep this channel open for

communications necessary for safety of navigation.”

The JOOW sees the PRC vessel altering its course towards his vessel’s course on a collision course.

PRC: “U.S. Navy Warship, this is PRC Warship. You are on a collision course. I am the

stand-on vessel.23 Alter your

course and speed and maintain a safe distance in accordance with the rule.”

U.S. Navy: “PRC Warship, this is U.S. Navy Warship. I am a sovereign, immune U.S.

Navy vessel conducting lawful military operations beyond the territorial seas of any nation. I am operating in a

safe and professional manner with due regard for the safety of my crew and all other vessels in the area. Your

unsafe actions create a serious risk of collision and put our crews’ safety at risk. Cease your unsafe and

unprofessional actions.”

In this example, though the PRC ship set a collision course and blamed the United States for the same, the PRC

ship does not actually seek a collision. It aims to intimidate, raise doubts, and encourage second-guessing. In

line with Sun Tzu’s teaching, through lawfare, the PRC pursues “breaking the enemy’s resistance without

fighting.”24 The PRC is pushing a

narrative that they are legitimate and the United States is in the wrong. However, this false narrative is

historically inaccurate.

In 1945, on what would become known as Retrocession Day, Chief Executive of Taiwan Province Chen

Yi (right) accepting the surrender of Taiwan from Rikichi Andō (left), the last Japanese Governor-General of

Taiwan, on behalf of the Republic of China Armed Forces at Taipei City Hall. (Credit: POWWII)

A Tale of Two25

China,26 which has referred to

itself as Zhōng-guó—the “Middle Kingdom” or “Central Nation”—since 220 BC,27 is the longest-running continuous

civilization.28 For at least two

millennia, a succession of Chinese dynasties29 ruled over tian xia—“all under heaven.”30 Chinese principles of governance and precepts of

culture endured through periods of unity, collapse, autonomy, and reunification.31 The imperial era closed with the Revolution of

1911; Chinese revolutionaries overthrew the Qing Dynasty and established the Republic of China (ROC), which they

called Zhōnghuá Mínguó. 32

Division and foreign intervention plagued the ROC’s rule of mainland China.33 At the outset, Mongolia declared independence in

Outer Mongolia during the Revolution of 1911.34 The Mongolian People’s Republic became a Soviet satellite state,35 and the ROC signed a treaty with

Russia over Mongolia in 1915, regained control of it by force from Russia in 1919, and then lost control again

in 1921.36 Russia also colonized

Tannu Tuva (Tyva), a region between Russia and Mongolia.37 Further, civil war erupted in the late 1920s between the ruling

Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist) Party and the Soviet-backed Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which calls itself

the Zhōngguó Gòngchăndăng, or Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCCP).38

The ROC initially suppressed the CCP’s rebellion and forced the retreat known as the Long March, but the 1931

Japanese invasion eventually unraveled the ROC’s control of mainland China.39 Japan launched a full-scale invasion in 1937,

resulting in Japanese control of Manchuria and most of the larger cities of eastern China, including Hong

Kong.40 An intermission in the

civil war between the ROC and the CCP enabled the ROC to prioritize focus and revenue on fighting Japanese

forces, but ROC forces failed to prevent destruction and stop Japanese atrocities.41 Meanwhile, the CCP focused on the “battle for

the hearts and minds of the peasants,” distributing landlord lands to laborers.42

After World War II, the CCP enjoyed popularity, with many Chinese people having a stake in the CCP’s success,

while the ROC autocracy felt hostile towards the Chinese people.43 Ultimately, after an agreement to govern a united China failed, fighting

broke out between the ROC and CCP in 1948.44 In 1949, the ROC and 1.2 million Chinese nationalists fled to Taiwan,

which Japan returned to the ROC at the end of World War II.45

Since 1949, the CCP has exercised control over mainland China under an autocratic socialist system.46 Mao Zedong, CCP chairman,47 initially planned on using the

name Zhōnghuá Mínguó (Republic of China) for his new government but assessed the people wanted a new, more

appropriate title.48 On 1 October

1949, Mao declared the creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—or Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó. 49 The United Nations, however,

continued to recognize the ROC as “China” until 1971.50 Then, in 1979, the United States recognized the CCP’s PRC51 has a “One China”

principle—without agreeing with the PRC position—and committed domestically to unofficial relations with and

defensive assistance of Taiwan via the U.S.-PRC Shanghai Communiqué and the Taiwan Relations Act.52 The CCP and the CCP’s PRC have

never exercised control over Taiwan or its outlying islands, including Kinmen Island, the Matsu Islands, or the

Penghu Islands.53

“You’ll Remember You Belong to Me”54

The PRC has been waging and winning lawfare from its founding.55 Today, the CCP’s PRC argues that, in 1949, the Chinese people proclaimed

the PRC’s replacement of the ROC as the only government of “the whole of China.”56 Further, the CCP asserts that it represents the

“entire Chinese People” and that foreign forces are “interfering with the reunification of China”—a domestic

issue.57 The PRC’s lawfare has

achieved some success. For example, in 1971, the United Nations recognized the PRC as “China” and expelled the

ROC, which was a founding member and a member of the Security Council since 1945.58 Additionally, the majority of the international

community refers to the PRC as “China,” despite the PRC’s increasingly expansive definition of its borders and

claims.59 We simply are not using

the word “China” the same way. However, the PRC’s vagueness and inaccuracies enable counter-lawfare on two core

issues: its people and its borders

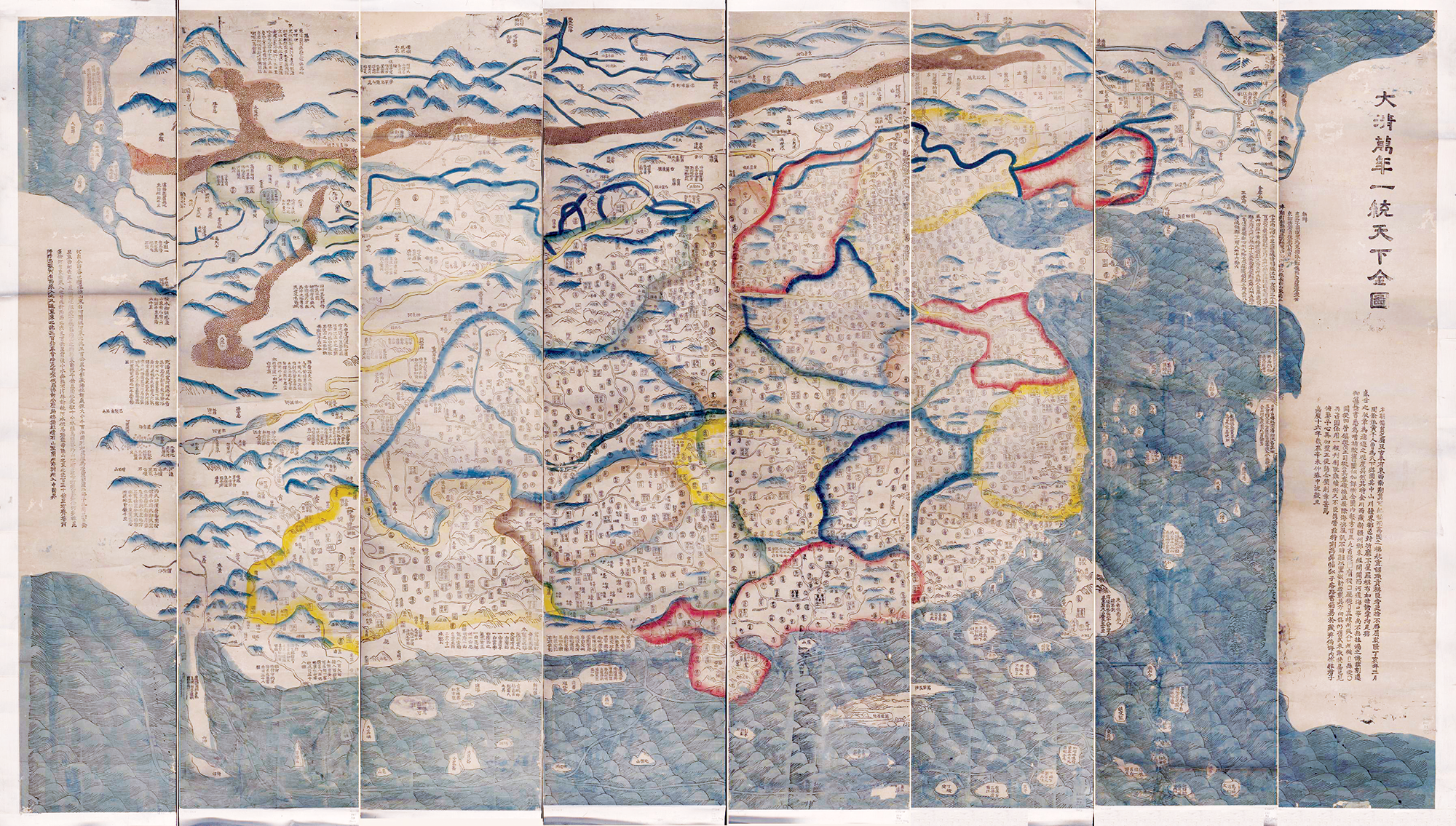

The Qing Dynasty complete map of “all under heaven,” essentially depicting all land as Chinese.

(Credit: Library of Congress)

Chinese Is a Worldwide Ethnicity Separate from the PRC State

First, not all ethnic Chinese people living across the globe are residents of the PRC. Han Chinese represent 95

percent of the Taiwanese population, 74 percent of the Singaporean population, and 20 percent of the Malaysian

population.60 Additionally, 5.4

million Chinese Americans live in the United States.61 The PRC refers to these Chinese people as “overseas Chinese” and has a

government office for outreach to them.62 Therefore, when we refer to the PRC as “China” and to the people of the

PRC as “Chinese,” we alienate ethnic Chinese from their nationality, pushing them towards siding with the PRC,

and lose the hearts and minds of potential partner nations.

Conversely, not all residents of the PRC are Chinese. Of the PRC’s population of 1.4 billion people, 91 percent

are Han Chinese and 6.7 percent were members of the CCP as of 2021.63 However, 9 percent of the PRC population—about

130 million people—are fifty-six other ethnicities, including Manchu, Tibetan, Mongol, and Korean.64 A simplistic attitude towards

PRC residents overlooks potential domestic division

The PRC’s Borders Do Not Include “All Under Heaven”

Second, the PRC’s borders include only the land it controlled in 1949 as well as Hong Kong and Macau, which it

subsequently acquired via treaties with the United Kingdom and Portugal, respectively.65 Neighboring nations, including Mongolia, India,

Nepal, and Vietnam66 are

sovereign—regardless of Han Chinese populations—with their own territorial waters and exclusive economic zones

in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.67 The PRC’s release of its 2023 “standard map” to

include portions of Bhutan and India and its creation of settlements in those newly claimed portions of “China”

violate international law.68 To

prevent the normalization of the use of force to move international boundaries, the United States and its

partners must publicize obedience to international law and criticize its violations.69

Conclusion

The PRC’s basic lawfare, which is part of its daily operations, includes arguing that the PRC is obeying the law

and the opposing side is violating international law. When the international community conflates “Chinese” with

“resident of the PRC,” they alienate ethnic Chinese globally. Moreover, referring to the PRC as “China” risks

signaling the conveyance or acquiescence of PRC authority over territories the PRC claims or with Chinese

populations, and it plays into the PRC’s lawfare tactics. To avoid these unintended implications, the

international community should loudly criticize international law violations, particularly the use of force to

move international boundaries. In addition, officials, military, academics, and citizens of the United States

and partner nations can counter PRC lawfare of expansive “Chinese” claims by simply referring to the PRC as “the

PRC.” TAL

Notes

1. Lawfare, Cambridge Dict., https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/lawfare (last visited Feb.

13, 2024).

2. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) People’s Republic of

China’s (PRC) “one-China principle has a clear and unambiguous meaning, i.e. there is but one China in the

world, Taiwan is an inalienable part of China, and the Government of the [PRC] is the sole legal government

representing the whole of China.” Questions and Answers Concerning the Taiwan Question (2): What is the

one-China principle? What is the basis of the one-China principle?, Mission of the People’s Republic of

China to the Eur. Union (Aug 15, 2022), http://eu.china-mission.gov.cn/eng/ more/20220812Taiwan/202208/t20220815_10743591.

htm; cf., The U.S. “One China Policy” vs. the PRC “One China Principle,” U.S.-Taiwan Bus. Council (

1, 2022), https://www.us-taiwan.org/resources/

faq-the-united-states-one-china-policy-is-not-the-same-as-the-prc-one-china-principle

(distinguishing the United States’ “One China Policy” as merely acknowledging that the PRC holds the

position that Taiwan is part of the PRC).

3. Joint Communique on the Establishment of Diplomatic

Relations Between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China, 2 Pub. Papers 2264,

2264-65 (Dec. 15, 1978) (establishing what is commonly referred to as the United States’ “One China”

Policy); see also Michael J. Green & Bonnie S. Glaser, What Is the U.S. “One China” Policy, and Why Does it

Matter?, Ctr. for Strategic & Int’l Studs. (Jan. 13, 2017), https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-us-one-china-policy-and-why-does-it-matter

(distinguishing the United States’ “One China Policy” as recognizing that the CCP’s PRC has a “one-China

principle” without agreeing that the PRC has sovereignty over Taiwan or even stating what “China” means).

4. A similar version of the first two paragraphs of this

section appear in Lieutenant Colonel Richard Connaroe’s article, Lawfare and Counter Lawfare from the 2024

Taiwan Earthquake, Nat’l Sec. L.Q., no. 2, 2024, 34 (explaining what lawfare and counter-lawfare are using

the 2024 Taiwan earthquake as an example).

5. In 2001, Jill Goldenziel provided two expansive

definitions of lawfare. See Jill Goldenziel, Law as a Battlefield: The U.S., China, and the Global

Escalation of Lawfare, 106 Cornell L. Rev. 1085, 1094 (2021)

6. See, e.g., Goldenziel, supra note 5, at 1099 (posing five

bins of lawfare: “battlefield exploitation lawfare,” “instrumental lawfare,” “proxy lawfare,” “information

lawfare,” and “institutional lawfare”); Orde F. Kittrie Lawfare: Law as a Weapon of War 11 (2016)

(suggesting two types of lawfare: “instrumental lawfare" and “compliance-leverage lawfare”).

7. Goldenziel, supra note 5, at 1099.

8. Id.

9. Id.

10. Id.

11. Id. at 1100.

12. See Dean Cheng, Heritage Found., No. 2692, Winning

Without Fighting: Chinese Legal Wa (2012), https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/winning-without-fighting-chinese-legal-warfare#_ftnref3.

13. Id. at 1-2.

14. Id. at 1

15. Id. (quoting Han Yanrong, Legal Warfare: Military

Legal Work’s High Ground: An Interview with Chinese Politics and Law University Military Legal Research

Center Special Researcher Xun Dandong, Legal Daily (PRC) (Feb. 12, 2006)).

16. Id. at 1-2.

17. See J06 Office of the Staff Judge Advocate, U.S.

Indo-Pac. Command,https://www.pacom.mil/Contact/ Directory/J0/J06-Staff-Judge-Advocate (last visited

Apr. 26, 2024).

18. The United Nations refers to the sea to the south of

the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the “South China Sea,” whereas the PRC refers to it as the “South

Sea” (Nan Hai), Vietnam refers to it as the “East Sea,” and the Philippines refers to it as the “West

Philippine Sea.” Bryan Lynn, What’s in a Name? South China Sea Claimants Seek to Remove ‘China,’ Learning

Eng. (Jul 24, 2017), https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/

whats-in-a-name-south-china-sea-claimants-seek-to-remove-china/3953830.html.

19. Hannah Beech, Just Where Exactly Did China Get the

South China Sea Nine-Dash Line From?, Time (July 19, 2016), https://time.com/4412191/nine-dash-line-9-south-china-sea (explaining that the

Republic of China first asserted a U-shaped, 11-dash line through the South China Sea on a Chinese map in

1947 to assert maritime claims, but it later removed two dashes around the Gulf of Tonkin under an agreement

with Vietnam to create the 9-dash line).

20. Uptin Saiidi, Here’s Why the South China Sea Is Highly

Contested, CNBC (Feb. 7, 2018), https://www.

cnbc.com/2018/02/07/heres-why-the-south-china-sea-is-highly-contested.html.

21. Seinfeld: The Finale (2) (NBC Network May 14, 1998).

In the closing lines of the series finale, Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza repeat the opening lines from

the pilot episode. Compare id., with Seinfeld: Pilot (NBC Network July 5, 1989). After Jerry asks about

button placement on a jacket, George asks, “Haven’t we had this conversation before?” and the pair agree

that “maybe we have.” Seinfeld: The Finale (2) (NBC Network May 14, 1998).

22. Naval vessels of the PRC may also identify themselves

as “People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Warship.” See, e.g., Xavier Vavasseur, US DoD’s 2021 China Military

Power Report: PLAN Is the Largest Navy in the World, Naval News (Nov. 5, 2021) https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/11/

us-dods-2021-china-military-power-report-plan-is-the-largest-navy-in-the-world.

23. The “stand-on vessel” is the vessel with the right of

way, and other vessels are to give way. Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing

Collisions at Sea, Oct. 20, 1972, 28 U.S.T. 3459, 1050 U.N.T.S. 16. In this scenario, the PRC vessel is

incorrectly asserting to be the stand-on vessel. See id.

24. Sun Tzu, The Art of War 8 (Lionel Giles tra Allandale

Online Pub., 2020) (n.d.).

25. Charles Dicken, A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

26. The name “China” comes from a pronunciation of

“Qin”—said “Cin” or “Cinese”—during foreign trade with the Qin dynasty. Joshua J. Mark, Ancient China, World

Hist. Encyc. (Dec. 18, 2012), https://www.

worldhistory.org/china.

27. Explore All Countries – China, The Wor Factbook:

CIA.gov (Feb. 13, 2024), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/china; see also, Origin of the Name

of Zhongguo, ChinaCulture.org, http://en.chinaculture.org/library/2008-02/11/content_22969.htm (last visited Feb.

20, 2024) (discussing the origin of the word zhongguo).

28. See Henry Kissinger, On China 2-7 (2011)

29. See List of Rulers of China, Met Museum (Oct. 2004),

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chem/ hd_chem.htm.

30. Kissinger, supra note 28, at 7, 10 (explaining that

China appears to understand borders between societies as not based on geographic or political demarcations

but instead on cultural distinctions).

31. Id. at 6-7.

32. History, Gov’t Portal of Republic of China (Taiwan),

https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_3.php (last visited Feb. 20, 2024); Explore All

Countries – China, supra note 27.

33. See Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27; see

also Beech, supra note 19 (explaining that the ROC first asserted a U-shaped, eleven-dash line through the

South China Sea on a Chinese map in 1947 to assert maritime claims but later removed two dashes around the

Gulf of Tonkin under an agreement with Vietnam to create the nine-dash line).

34. Mongolia was known as “Outer Mongolia” throughout the

Qing Dynasty. See Mongolia: Independence and Revolution, Britannica, https://

www.britannica.com/place/Mongolia/Independence-and-revolution (last visited Feb. 20, 2024). Inner

Mongolia, which attempted to declare independence at the same time as Outer Mongolia, is a province of the

PRC today. Id.

35. Explore All Countries – Mongolia, The Wor Factbook:

CIA.gov (Feb. 6, 2024), https://www.cia. gov/the-world-factbook/countries/Mongolia.

36. China/Mongolia (1911-1946), Univ. of Cent. Ark., https://uca.edu/politicalscience/dadm-project/asiapacific-region/chinamongolia-1911-1946

(last visited Feb. 20, 2024).

37. Mongolia: Independence and Revolution, supra note 34.

38. Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27; Chinese

Communist Party, Britannica (Feb. 18, 2024), https://

www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-Communist-Party.

39. Who Lost China?, Harry S. Truman Lib. & Museum, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/who-lost-china (last

visited Feb. 20, 2024).

40. Id.; Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27;

Chinese Civil War 1945-1949, Britannica,

https://www.britannica.com/event/Chinese-Civil-War/The-tideturns-1947-48 (last visited Apr. 26,

2024).

41. Who Lost China?, supra note 39; see also Const. Rts.

Found., Why Did the Communists Win the Chi Revolution? (2016),

https://www.crf-usa.org/images t2t/pdf/WhyDidCommunistsWinChineseRevolution. pdf.

42. Const. Rts. Found., supra note 41, at 2 (explainin

that the CCP distributed landlords’ lands to the peasants, who then felt a stake in CCP success).

43. Who Lost China?, supra note 39; The Chinese Civil War:

Why Did the Communists Win?, Bill of Rts. Action, Summer 2014, at 1, 3-4,

https://www.crf-usa. org/images/pdf/gates/chinese-civil-war.pdf

44. Chinese Civil War 1945-1949: The Tide Turns (1947-

48), Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Chinese-Civil-War/The-tide-turns-1947-48 (last

visited Feb. 20, 2024).

45. Id.; History, supra note 32. The Qing dynasty ceded

Taiwan to Japan at the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. History, supra note 32. The ROC’s forces

accepted the Japanese surrender in 1945, and the ROC, the United States, and the United Kingdom issued the

Potsdam Declaration, which carried out the Cairo Declaration of returning the island of Formosa (Taiwan) to

the ROC. Id.

46. See Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27.

47. Currently, “Xi Jinping is the general secretary of the

Chinese Communist Party (CCP), chairman of the CCP Central Military Commission, president of the People’s

Republic of China (PRC), and the chairman of the PRC Central Military Commission” in that order of priority.

Chinese Government Leadership, U.S.-China Bus. Council,

https://www.uschina.org/resourcechinese-government-leadership (last visited Apr. 26, 2024) (listing

CCP position as primary and president of PRC as third in priority).

48. See Richard C. Bush, Thoughts on the Republic of China

and Its Significance, Brookings (Jan. 24, 2013) https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/thoughts-on-the-republic-of-china-and-its-significance.

49. Who Lost China?, supra note 39.

50. History, supra note 32; G.A. Res. 2758 (XXVI) (Oct.

25, 1971).

51. The CCP is the essence of the PRC as much as the Nazi

Party was the essence of Nazi Germany in that the CCP leaders are the PRC leaders. See Kerry Gershaneck, To

Win without Fighting, Marin Corps Univ. (June 17, 2020),https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Expeditions-with-MCUP-digital-journal/To-Win-without-Fighting

(defining the PRC’s political warfare); see also Chinese Government Leadership, supra note 47.

52. Joint Communique on the Establishment of Diplomatic

Relations Between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China, 2 Pub. Papers 2264 (Dec.

15, 1978); U.S. Relations With Taiwan, U.S. Dep't of State (Aug. 31, 2018), https://www.state.gov/us-relations-with-taiwan; 22 U.S.C. § 3301 (noting that the

United States recognized Taiwan as the ROC prior to 1979). The United States has no obligations to Taiwan

directly, as the Taiwan Relations Act is a domestic commitment. See 22 U.S.C. § 3301.

53. See History, supra note 32 (noting ROC victory in the

25 October 1949 Battle of Kuningtou on Kinmen Island); Alan Taylor, Taiwan’s Kinmen Islands, Only a Few

Miles From Mainland China, Atlantic (Oct. 8 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2015/10/

taiwans-kinmen-islands-only-a-few-miles-from-mainland-china/409720 (noting Kinmen is a few miles

away from the mainland and to the west of Taiwan); Quemoy Island, Britannica (Feb. 20, 2024) https://www.britannica.com/place/Quemoy-Island (explaining that Kinmen Island is one

of twelve Quemoy Islands); Matsu Island, Britannica (Feb. 8 2024), https://www.britannica.com/place/Matsu-Island (noting nineteen Matsu Islands 130

miles north of Taiwan and off the mainland coast); P’eng-hu Islands, Britannica (Feb. 17, 2024), https://www.britannica.

com/place/Peng-hu-Islands (noting sixty-four Penghu Islands 30 miles west of Taiwan); see also

Masahiro Kurosaki, Reformulating Taiwan’s Statehood Claim Lawfare (Sept. 14, 2023), https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/reformulating-taiwan-s-statehood-claim

(discussing Taiwan statehood to deter PRC invasion).

54. Hamilton (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures 2022).

In the song “You’ll Be Back,” King George III erroneously fantasizes that the U.S. colony is his “forever

and ever and ever and ever and ever.” Id.

55. See, e.g., Huizhong Wu, For Taiwan’s Olympics Team,

Everything Is in a Name, AP (Feb. 2, 2022), https://apnews.com/article/winter-olympics-sports-beijing-taiwan-taipei-13f0f1769874557dad489b0675605096

(discussing the Olympic Committee decision to prevent athletes from competing as Republic of China or Taiwan

in 1981 as a result of PRC efforts).

56. See, e.g., The One-China Principle and the Taiwan

Issue, China.org, http://www.china.org.cn/english/taiwan/7956.htm (last visited Feb. 20, 2024).

57. Id.

58. James Carter, When the PRC Won the ‘China’ Seat at the

UN, China Project (Oct. 21, 2020), https:// thechinaproject.com/2020/10/21/when-the-prc-won-the-china-seat-at-the-un; see

G.A. Res. 2758 (XXVI) (Oct. 25, 1971).

59. The PRC’s 2021 Land Borders Law purports to

“standardize and strengthen” border control and communicates the PRC’s intent to “resolutely defend

territorial sovereignty and land border security”; its 2023 “standard map” expands PRC boundaries to include

disputed areas and sovereign territory of other nations—notably Bhutan. See Jill Goldenziel, How to Decode

China’s Imperial Map —and Stop It from Becoming Reality, Forbes (Sept. 5, 2023, 2:11 AM EDT), https://

www.forbes.com/sites/jillgoldenziel/2023/09/05/how-to-decode-chinas-imperial-map-

and-stop-it-from-becoming-reality/?sh=639dc6ef5a2d (discussing the 2023 standard map of China and

its inclusion of the “Nine-Dash Line” among other controversial features); U.S. Indo-Pac. Command SJA

Tactical Aid Series, The PRC’s Law (2023) [hereinafter PRC’s Land Borders Law], https://www.pacom.mil/Portals/55/Documents/Legal/J06%20TACAID%20-%20PRC%20LAND%20BORDERS%20LAW%20-%20FINAL.pdf?ver=zp6y0pfpaAWoL5KOv0KDYg%3D%3D

(a counter lawfare piece originally by Major Jayne Leemon that exposes PRC malfeasance/lawfare in the PRC’s

2023 Land Borders Law and its “standard map” and establishes why the international community must reject

it).

60. Explore All Countries – Taiwan, World Factbook:

CIA.gov (Feb. 13, 2024),https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/taiwan; Explore All Countrie –

Singapore, World Factbook: CIA.gov (Jan. 31, 2024), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/singapore; Explore All Countries –

Malaysia, World Factbook: CIA.gov (Feb. 13, 2024), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/malaysia; Explore All Countries –

China, supra note 27.

61. Abby Budiman & Neil G. Ruiz, Key Facts about Asian

Americans, a Diverse and Growing Population, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Apr. 29, 2021), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans.

62. See, e.g., President Hu Calls for More Role of

Overseas Chinese, Embassy of the People’s Republic of Chi the United States of America (Mar. 8, 2008),http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/ywzn/lsyw/oca/200803/t20080308_4904531.htm;

Overseas Chinese Affairs, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the unitedStates of America, http://us.china-embassy.gov.eng/ywzn/lsyw/oca (last visited Feb. 20, 2024).

63. Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27; Yew Lun

Tian, Factbox: A Hundred Years on, How the Communist Party Dominates China, Reuters (June 29, 2021),

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/hundred-years-how-communist-party-dominates-china-2021-06-30.

64. Explore All Countries – China, supra note 27.

65. Joint Declaration on the question of Hong Kong (with

annexes), China-U.K., Dec. 19, 1984, 1399 U.N.T.S. 33; Joint Declaration of the Government of the People’s

Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of Portugal on the Question of Macao, China-Port., Apr.

13, 1987.

66. The PRC invaded Vietnam in 1979 for its alleged

alignment with the Soviet Union. Nguyen Minh Quang, The Bitter Legacy of the 1979 China-Vietnam War, The

Diplomat (Feb. 23, 2017), https://thediplomat.com/2017/02/the-bitter-legacy-of-the-1979-china-vietnam-war. The

invasion failed after less than a month of fighting. Id.

67. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, arts.

3, 55-57, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 (stating a state has the right to establish a territorial sea up

to 12 nautical miles and an exclusive economic zone up to 200 nautical miles from the territorial sea); see

also Goldenziel, supra note 5, at 1103 (discussing coastal states’ entitlements of 12 nautical miles of

territorial sea and 200 nautical miles of exclusive economic zone).

68. See PRC’s Land Borders Law, supra note

69. As analogues, in 2022, the world witnessed Russia

invade Ukraine, which Russia had for years called “the Ukraine” and its capital Kiev instead of Kyiv,

allegedly to protect native Russians and Russian-speaking people; these acts are similar to Hitler’s goal of

uniting German-speaking people in the 1930s. See, e.g., Patrick Donahue & Daryna Krasnolutska, Understanding

the Roots of Russia’s War in Ukraine, Bloomberg (Mar. 2, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/

articles/2022-03-02/understanding-the-roots-of-russia-s-war-in-ukraine-quicktake ; Mark Rice-Oxley,

How to Pronounce and Spell ‘Kyiv’, and Why It Matters, Guardian (Feb. 25, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/25/how-to-pronounce-and-spell-kyiv-kiev-ukraine-and-why-it-matters.

Author

LTC Connaroe is the Deputy Staff Judge Advocate for 8th Theater Sustainment Command at Fort Shafter, Hawaii.