Soldiers of Siam

A First World War Chronicle

Reviewed by Barry M. Stentiford

Article published on: June 1, 2024 in the Army History Summer 2024 issue

Read Time: < mins

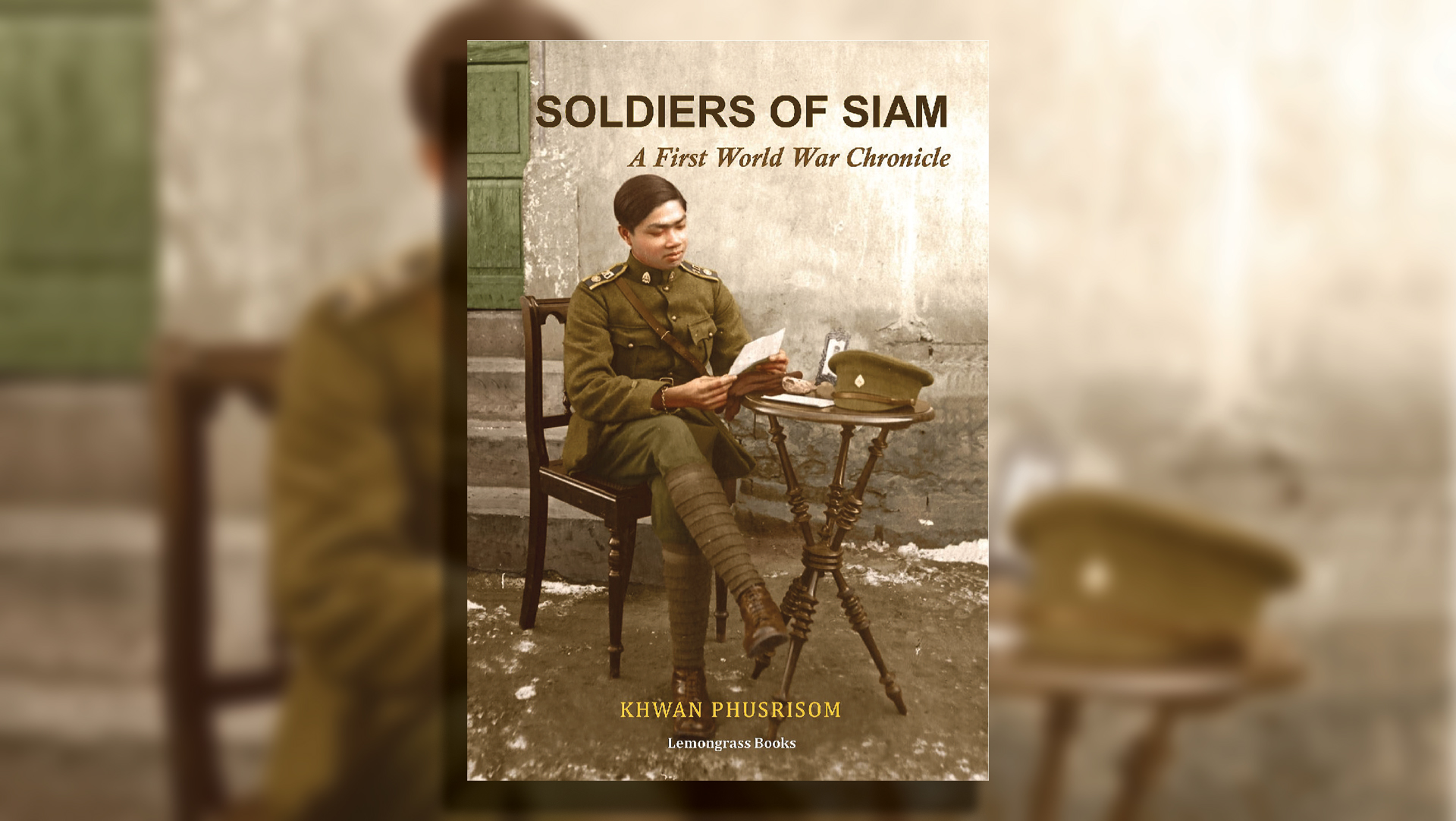

SOLDIERS OF SIAM: A FIRST WORLD WAR CHRONICLE, BY KHWAN PHUSRISOM, Lemongrass Books, 2020 Pp. vi, 192. $25

Siam, modern Tailand, is the only country in Southeast Asia that was never colonized. It achieved that feat by

resisting when possible and yielding when necessary during the years of imperialist expansion. It simultaneously

instituted reforms that made the kingdom more legitimate to the Europeans. World War I presented Siam an

opportunity to solidify its independence by allying with France and Britain against Germany. Other factors were

also at work. King Vajiravudh (Rama VI, reigned 1910–1925), an honorary general of the British Army, studied law

and history at Christ Church, Oxford, and maintained personal connections with members of the British

aristocracy. Further, Vajiravudh was aware of German espionage within Siam and feared that his country would

become a target of German colonialism should Germany win.

Siam declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary on 22 July 1917. The kingdom raised an expeditionary force of

four battalions, which left Bangkok in June 1918. Te Siamese soldiers were grouped as Transportation, Medical,or

Air Service, although apparently, none of the soldiers had any prior training in

these specialties. Upon their arrival in

France, the medical soldiers were assigned

as hospital orderlies, the airmen began

training under French instructors, and

the transportation soldiers were taught to

drive and maintain their vehicles. Aferward,

the transportation soldiers were

assigned to the American Expeditionary

Forces (AEF).

Soldiers of Siam is a short volume that

is mainly a translation of a chronicle kept

by Sgt. Kleuap Kaysorn of the transportation

corps. His manuscript was translated

by Khwan Phusrisom, who added an

introduction that placed the war in the

context of Siam’s internal and external

relations and an epilogue examining the

results of the war. She holds a PhD in

Anglo-Tai relations and spent two years

in the Rhineland while working on the

book, making her uniquely qualifed to

translate the work.

Phusrisom uses the terms Siamese and

Thai interchangeably throughout the

book, as Sergeant Kaysorn apparently did

in his original chronicle. She makes clear

throughout the work that she sees German

conduct during the war and in its African

colonies before the war as inhumane,

and she ties Imperial Germany’s conduct

directly to the later rise and acceptance of

Nazi practices and ideology. She includes

two short chapters that give a brief overview

of the service of the medical and

aviation soldiers, as well as a short account

from another soldier in the transportation

corps of his experience in the Rhineland,

rounding out Kaysorn’s account.

Sergeant Kaysorn was a veterinarian,

not a professional soldier, when he volunteered

for the expeditionary force. He

lied about his age, claiming to be younger

than his 36 years. His patriotism and

devout Buddhism come through clearly

throughout the work. He has a keen eye

and a subtle sense of humor. His observations

of the wealth of Singapore; the

degradation of the people of Columbo,

Ceylon; and the difficulties of dealing

with the people of Port Sa’id, Egypt,

ofer intriguing glimpses into the world

at the height of the imperialist age. His

impressions of the French, the Americans,

and the Vietnamese are also valuable for

understanding the era. At frst, he was

taken aback by the lack of Asian brotherhood

shown by the Vietnamese. However,

afer seeing the abuse heaped on them

by the French, in sharp contrast to the

generally amiable attitude of the French

to the Siamese, he understood the role

colonialism played in the degradation of

a people.

Te transportation and medical troops

supported the AEF in the Meuse-Argonne

Ofensive in the later summer and fall

of 1918. Sergeant Kaysorn described the

hardships, dangers, and frustrations of

the Siamese in the campaign. Many of

the Siamese became ill during the frst

wave of the Spanish fu, which fortunately

lef those who recovered immune to the

later, more deadly wave. As a result, the

Siamese, although they lost troops to the

disease, apparently had a lower death rate,

which the Siamese soldiers attributed to

the natural immunity of Asians. After

the Armistice, the Siamese transportation

soldiers supported the French army in

the occupation of the Rhineland to pressure

Germany into signing the Treaty of

Versailles.

The Siamese soldiers spent several

months in the Rhineland, serving frst in

Mussbach and later in Hochspeyer. Te

European winter lef a strong impression

on the sergeant. Coming from a tropical

country, a typical winter in the Rhineland

was a miserable ordeal for the Siamese.

Equally chilly was the initial reception

from the Germans, and Kaysorn had to

grapple with his feelings about living

among people he recently had seen as the

enemy. Eventually, warmer relations grew,

but he became disappointed by some of his

colleagues who took German girlfriends,

which he believed brought shame to the

Siamese army.

In all, the Siamese Expeditionary Force

lost nineteen soldiers during the war,

fourteen of whom died from the Spanish

flu. Sergeant Kaysorn commented much

less on the return voyage to Bangkok, but

he did describe the tumultuous welcome the

soldiers received. Upon their return to Siam,

the pilots and aircraf mechanics formed

the nucleus of what became the Royal Tai

Air Force. Phusrisom added information on

Kaysorn’s life afer his return, and sadly it

was not a happy tale. On his way to his home

afer his discharge, carrying his military

service pay and the money the king gave him

for his chronicle, Kaysorn was robbed and

lef penniless. He eventually married and

had a family, but his wife died and he fell into

alcoholism and homelessness, possibly from

what today would be called post-traumatic

stress disorder. He eventually would be

rescued by one of his daughters but later died

in a road accident when he was 76.

Soldiers of Siam joins Stefan Hell’s Siam and World War I: An International History (River Books) from 2017 as the only currently available works in English about Siam in the Great War. Whereas Hell placed events in Siam at the center while also exploring the larger context of Siam’s participation, Soldiers of Siam is mostly the story of a single observant Siamese soldier, providing a less academic but more personal account. Kaysorn’s observations of the various people he encountered during his journey and in France ofer vivid images of a world that no longer exists. In a larger context, Soldiers of Siam provides an understanding of why small countries sometimes join alliances or participate in wars seemingly outside of their immediate interests. As such, Soldiers of Siam ofers a case study of how smaller countries can successfully navigate the treacherous waters of a major war to their advantage.

Author

Dr. Barry M. Stentiford is a professor of history at the U.S. Army School of Advanced Military Studies, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.