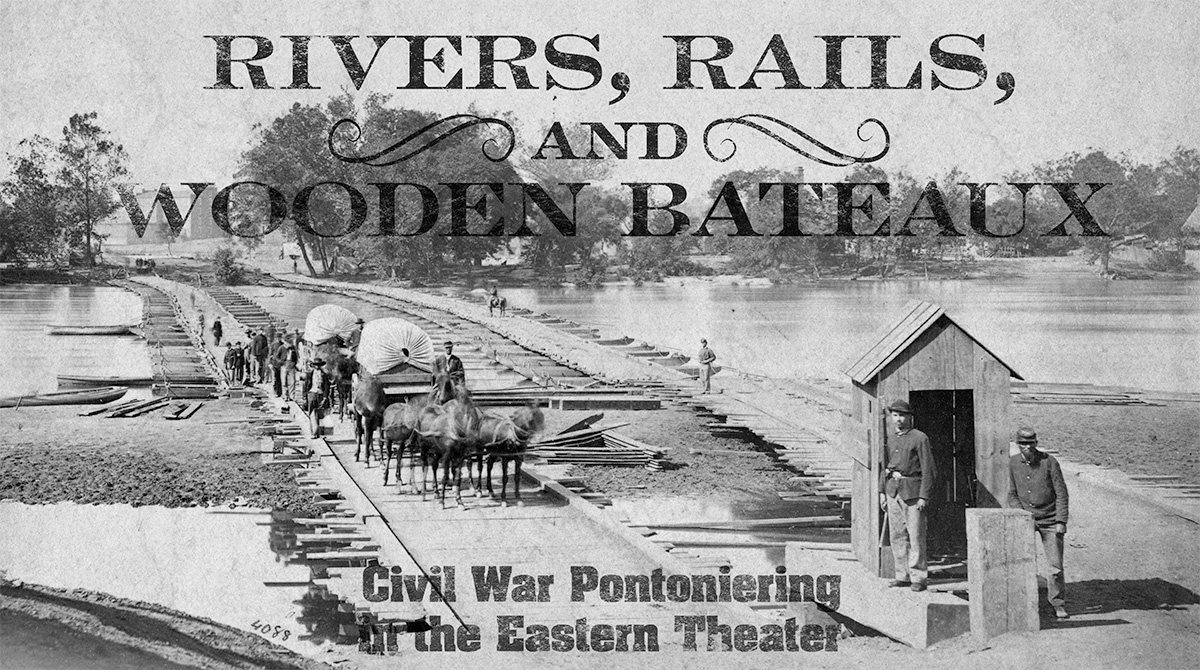

Rivers, Rails, and Wooden Bateaux

Civil war Pontoniering

By Mark A. Smith

Article published on: June 1, 2024 in the Army History Summer 2024 issue

Read Time: < 37 mins

Pontoon bridges across James River at Richmond, Virginia, ca. April,

1865

Library of Congress

During the American Civil War, the small number of regular officers and enlisted soldiers in the U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers fulfilled several important roles. They gathered tactical and operational intelligence through

field reconnaissance and mapped the local countryside to enable movements through a hostile environment. They

provided expertise and guidance in the construction of field fortifications and siege works and built

semipermanent defenses for important places behind the lines. Engineers also often directed the fatigue details

that made the abysmal Southern roads passable for large armies and their supply trains. In all these areas,

volunteer officers and soldiers also provided significant support, with and without the assistance of regular

engineers. However, the regular engineer officers provided critical leadership in the management of military

bridging. The development, organization, and army-level oversight of portable bridging equipment fell almost

entirely within their purview, though volunteer units often managed the bridge trains themselves in the field.

These operations literally kept the United States' armies on the march toward victory.

The engineers employed a variety of equipment and approaches, but these operations also followed larger

patterns. Historian Philip Shiman has illuminated some of these in the West, where Maj. Gen. William S.

Rosecrans designed a new canvas pontoon boat that was easier to maneuver across the poorer roads in that

theater. This so-called Cumberland pontoon, as later refined by engineer Capt. William E. Merrill, had a wooden

frame that could be folded in half and transported on a standard Army wagon.1 Pontoniering in Virginia, however, has been

understudied, a curious oversight given the many rivers and their impact on operations. An examination of

wartime military bridging in the East shows how Corps of Engineers officers crafted a system of portable

bridging that was best suited to the region’s geography and infrastructure and that enabled Lt. Gen. Ulysses S.

Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign and subsequent American successes.

Spanning History

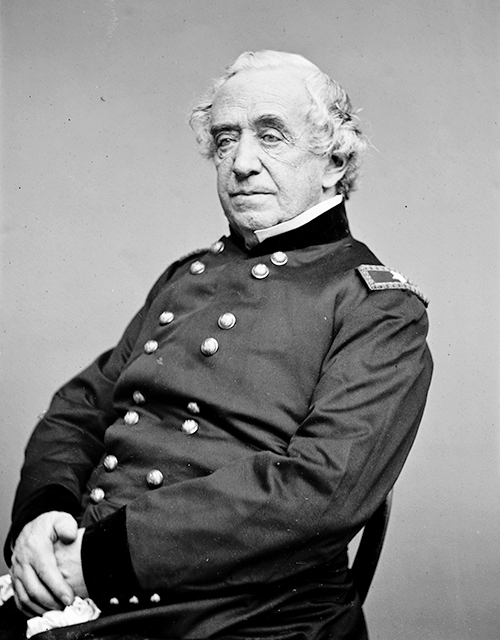

General Totten

Library of Congress

Military bridging, also called pontoniering for its reliance on specialized floating craft called pontoons or

pontoon boats, was not new to Americans during the Civil War. Largely because of the persistent efforts of Army

Chief Engineer Col. Joseph G. Totten, Congress authorized a single company of engineer soldiers in the spring of

1846, just after it declared war on Mexico.2 While the new unit rganized and deployed, Totten’s officers developed its

first bridge train. It relied on boats made of three inflatable natural rubber cylinders, but these proved less

than ideal over the long term. The rubber decayed over time in storage, and the boats were vulnerable to

punctures in the field, though pontoniers could make minor repairs with small rubber patches. Worse, the

floating cylinders could become unstable in the water; sometimes bridges made with them moved so much that they

were unsafe for animals. Despite their problems, when the Civil War started in 1861, the Army’s only portable

bridging equipment consisted of a half-rotted rubber train first made for the war against Mexico.3

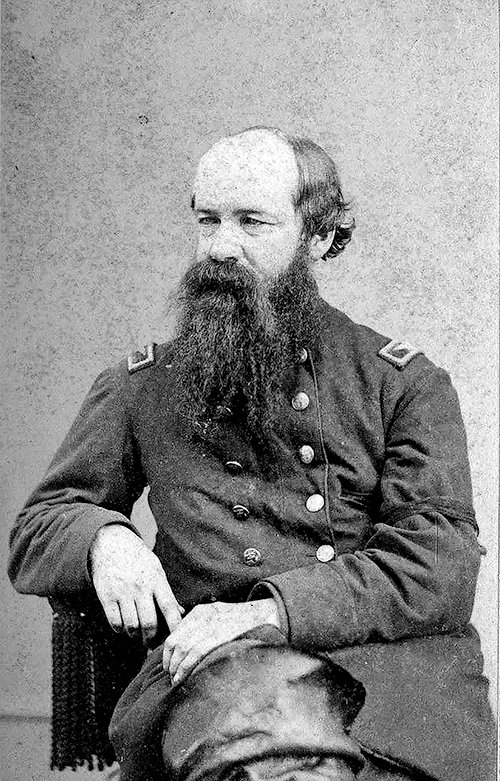

James C. Duane, shown here as a colonel

U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers

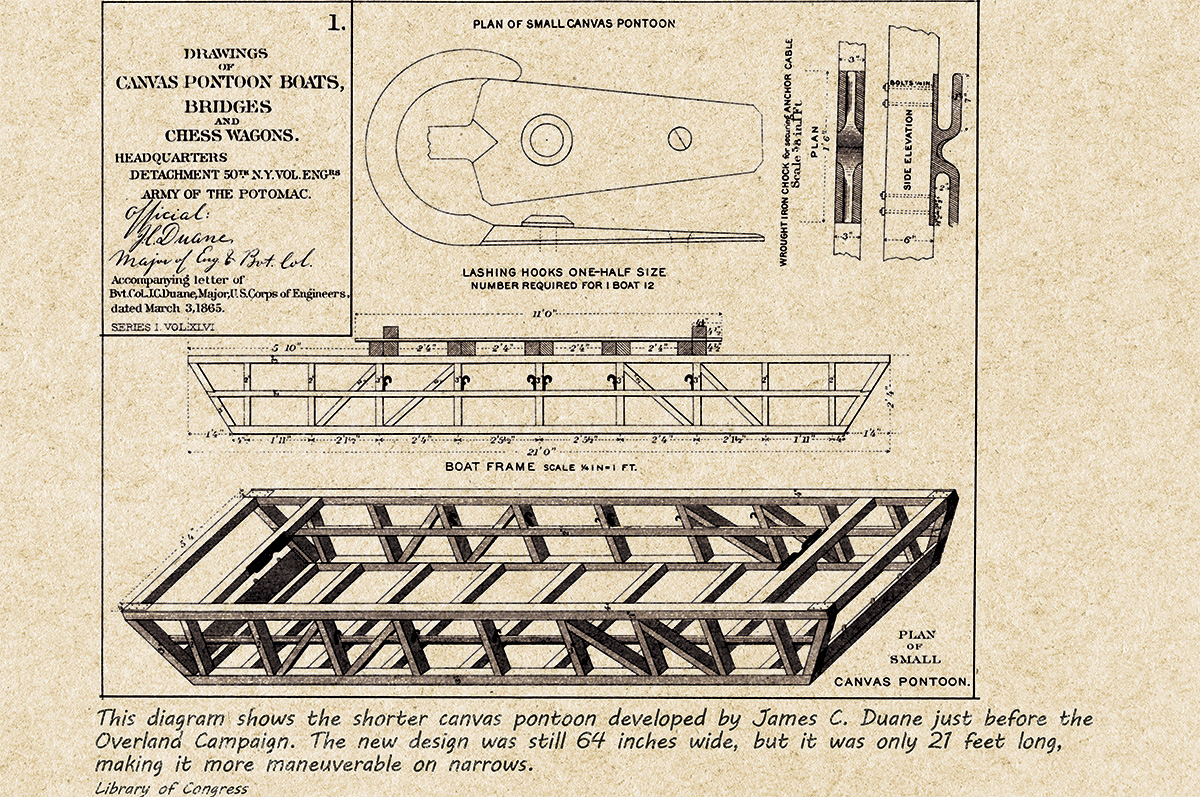

The engineers had carried out trials with other types of pontoons. In 1858, the commander of the antebellum

Engineer Company, Lt. James C. Duane, tested a variety of portable bridging materials. These included corrugated

iron pontoons; boats made of a canvas cover stretched over a wooden frame that were based on a Russian design; a

type of wooden bateaux used by the French army; the Austrian-designed Birago trestles for use in water too

shallow for pontoons; and a new rubber bridge train. In reviewing this equipment, Duane had to balance two main

considerations: the boats had to have sufficient structural integrity and buoyancy to support the heaviest field

guns and wagons while remaining light and portable enough to keep up with an army’s movements. The wooden boats

in Duane’s trials were 31 feet long and weighed nearly 1,300 pounds, but with considerable effort sixteen

pontoniers could carry them on their shoulders when required. Their sturdy design made them preferable where the

water was rougher, or the bridges needed to last longer. The canvas pontoons in the trials weighed about half

what the wooden ones did, so they were more portable, and the additional step of attaching the covers to the

frames hardly slowed trained pontoniers. However, the covers degraded over time in the water. The iron boats

weighed the most, making them the hardest to transport. Moreover, they were no stronger than the wooden pontoons

because their corrugations ran from bow to stern and so did not provide any additional support for the decking,

which rested on the boat’s gunwales. After his tests, Duane recommended the wooden boat for a field army’s main

pontoon train (sometimes called the reserve train) and the more mobile canvas boats for advance-guard trains,

with Birago trestles a part of both. He also considered transportation for the bridge train. The pontoon wagon

the French designed for their wooden bateaux had small wheels that would be likely to break down and more

difficult to maneuver on American roads, which were rougher and narrower than those throughout Europe. To adapt

to American conditions, Duane designed a wagon with larger wheels and a geared front axle that could turn in

narrower spaces. Although certainly an improvement over the French wagon, the new design remained larger and

less maneuverable than the army’s standard quartermaster wagon, and its geared axle mechanisms were susceptible

to breakdowns.4

A wooden bateaux loaded on its transport wagon at the camp of the 50th New York

Engineers near Rappahannock Station, Virginia, during the winter of 1863–1864.

Library

of Congress

Civil War Beginnings

Despite Duane’s trials, the Engineer Department still relied on rubber boat trains at the start of the Civil

War. In May 1861, Chief Engineer Totten ordered the New York Engineer Agency, which often supplied equipment and

materials to the army’s engineers, to obtain a new rubber pontoon train. In late July, Lt. Quincy A. Gillmore,

who ran the agency, shipped the new equipment to Washington where a small detachment of the Engineer Company

drilled with it. A few months later, Totten ordered another rubber train for future use, but as part of the

reorganization of the Army of the Potomac that fall, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan instructed the engineer

captain Barton S. Alexander to prepare several new bridge trains for the army. With Duane’s help, Alexander

repeated some of the earlier trials with Birago trestles and wooden, canvas, iron, and even the rubber pontoons,

after which the two engineers built McClellan’s army five wooden trains and several canvas ones, both

supplemented with the Austrian trestles.5

Captain Alexander

Library of Congress

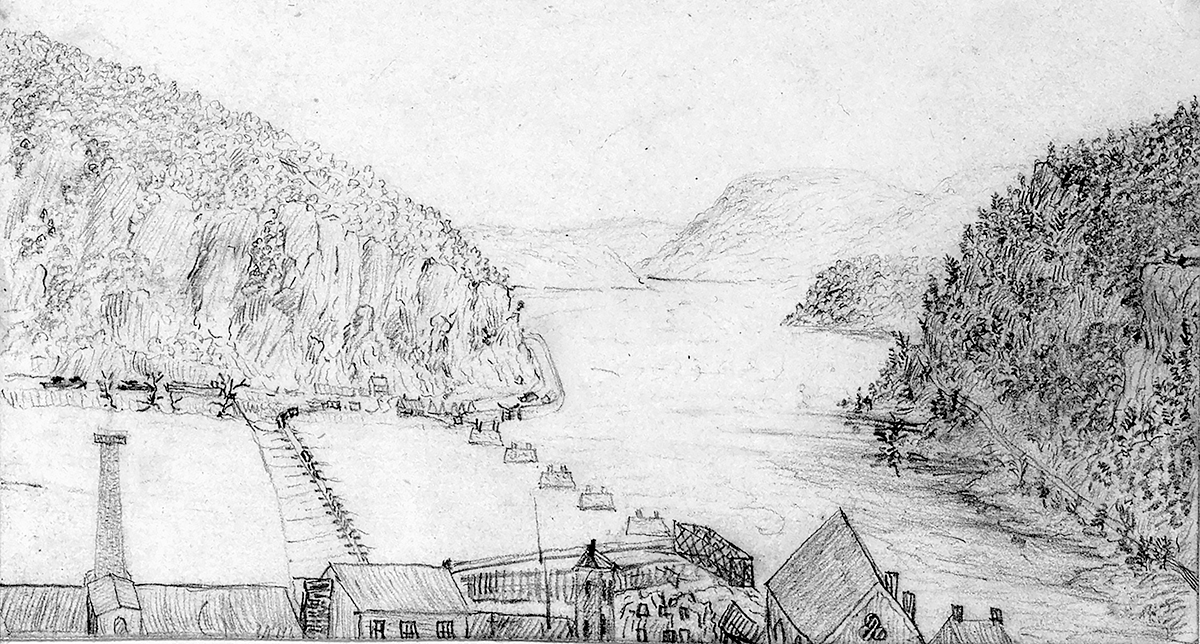

Early the next year, a recently established but informal battalion of regular engineer soldiers built the

country’s first wooden pontoon bridge at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, to clear rebel forces from the upper

Potomac River and begin restoring the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The battalion’s Company A (the original

Engineer Company) threw the bridge on 26 February, amid high winds and flood conditions, with the Potomac full

of ice and driftwood. Conditions were so difficult that the pontoniers had to add a hawser when heavy winds

almost pulled up the boat anchors. By day’s end, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’s division marched across an

840-foot bridge made from forty-one wooden bateaux, demonstrating the stability and sturdiness of the

pontoons.6

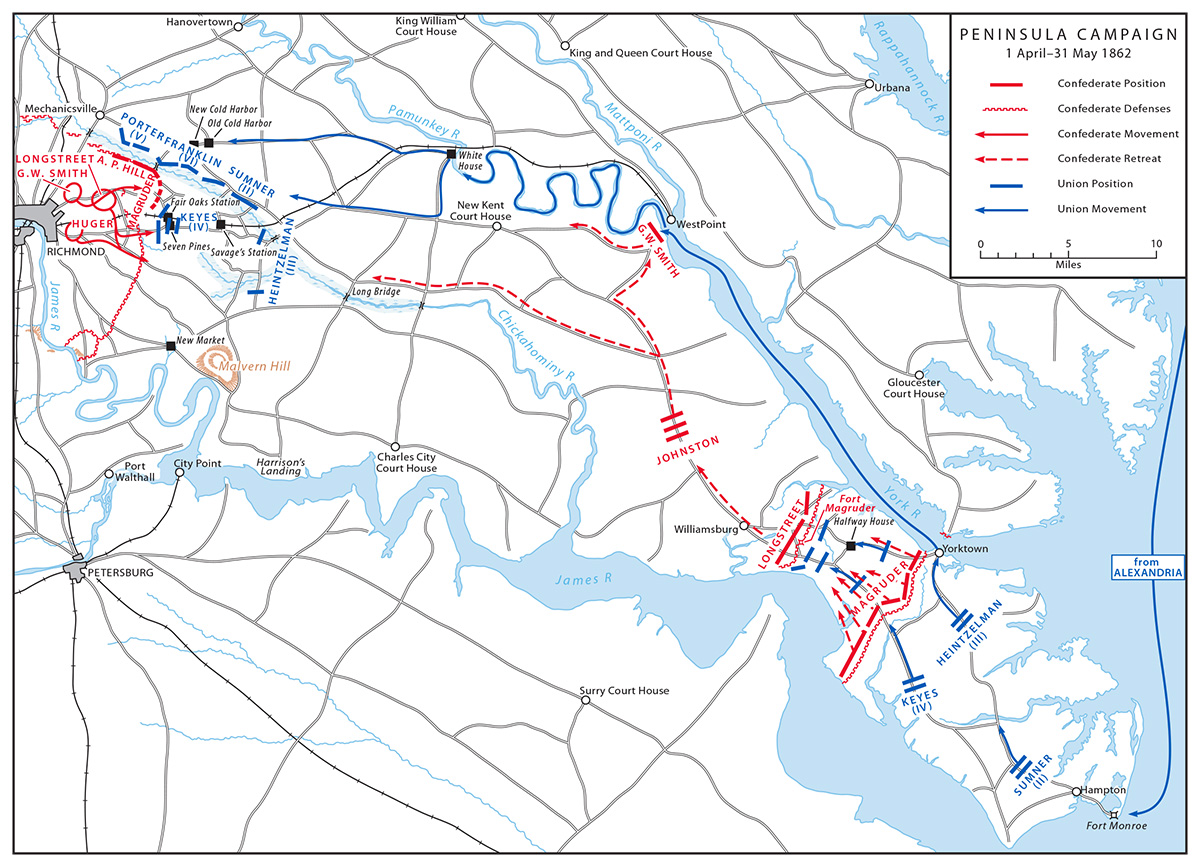

The Peninsula Campaign

In the spring of 1862, the Army of the Potomac brought six portable bridge trains on the Peninsula Campaign.

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan intended to land the army at Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula

between the James and York Rivers and then move against the Confederate capital of Richmond by marching up the

peninsula and crossing the Chickahominy River with his bridge trains if necessary. Each train contained

thirty-four pontoon wagons designed to carry a boat and related equipment, like the balks that connected

pontoons in a bridge as well as spring lines, oars, and anchors. Another twenty-two wagons bore the long wooden

planks, known as chess, which served as bridge decking. Four carried abutment materials, and four more carried

tools. Two traveling forges and eight of the Austrian trestles completed a train. The boats themselves were a

mixture of the wooden bateaux and canvas types, with the more durable but heavier wooden pontoons predominating.

Fully deployed, each train could span a river up to 700 feet wide, and multiple trains could be combined for

longer crossings.7

A canvas boat with its cover stretched over the frame and ready for

eployment

Library of Congress

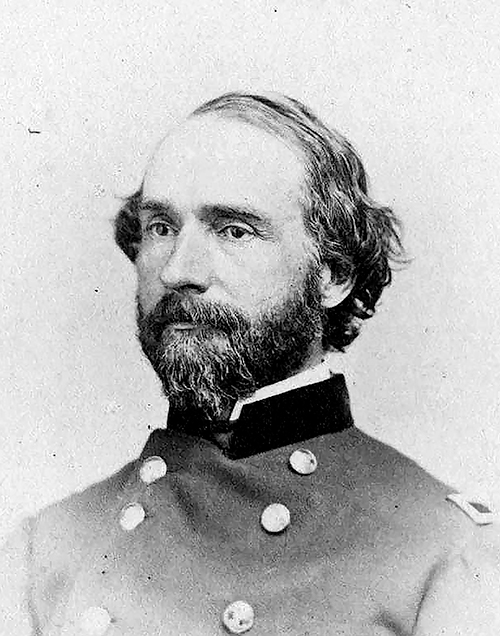

Specially trained units of engineer soldiers managed the bridge trains, a duty responsible for a third of their

popular designations as sappers, miners, and pontoniers. The Volunteer Engineer Brigade included two Empire

State regiments, the 15th and the 50th Regiments, New York State Volunteer Engineer Corps. Daniel P. Woodbury, a

major in the Regular Army Corps of Engineers who also held a volunteer brigadier general’s commission, commanded

this brigade. The officers and soldiers of the army’s one antebellum company of engineer soldiers had helped

train the New York engineer regiments during the winter of 1861–1862, even while raising and organizing two more

companies of regulars. James. C. Duane, now promoted to captain, led the three regular units (increased to four

following the Seven Days’ Battles in late June and early July). For ease of management, Duane combined the

regular companies into an ad hoc organization known as the Engineer Battalion,

though it lacked both formal authorization as a battalion and the regular complement of a battalion’s support

personnel. Both Duane’s battalion and Woodbury’s brigade were attached directly to McClellan’s headquarters once

on the peninsula, and this organization persisted in the East for the next two years, with the engineer troops

who served as pontoniers attached to Army of the Potomac headquarters.8

This drawing, by Gilbert Thompson of the U.S. Engineer Battalion, shows the first

military bridge thrown using wooden bateaux in February 1862.

Library of Congress

McClellan’s operations in Virginia provided a preview of some of the pontoniering challenges and their potential

solutions in the Eastern Theater. The first problem was organizational, and it may explain why the pontoniers

spent two years attached to army headquarters. Before leaving the area around Washington D.C., McClellan

originally assigned the Volunteer Engineer Brigade to Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s I Corps. When President Abraham

Lincoln retained that corps to shield the capital, it threatened to deprive the Army of the Potomac of most of

its engineer troops. Although McDowell’s

corps never joined McClellan on the peninsula, Secretary of War

Edwin M. Stanton returned the volunteer engineers to McClellan’s command before operations reached the rebel

defenses at Yorktown, 20 miles beyond Fort Monroe.

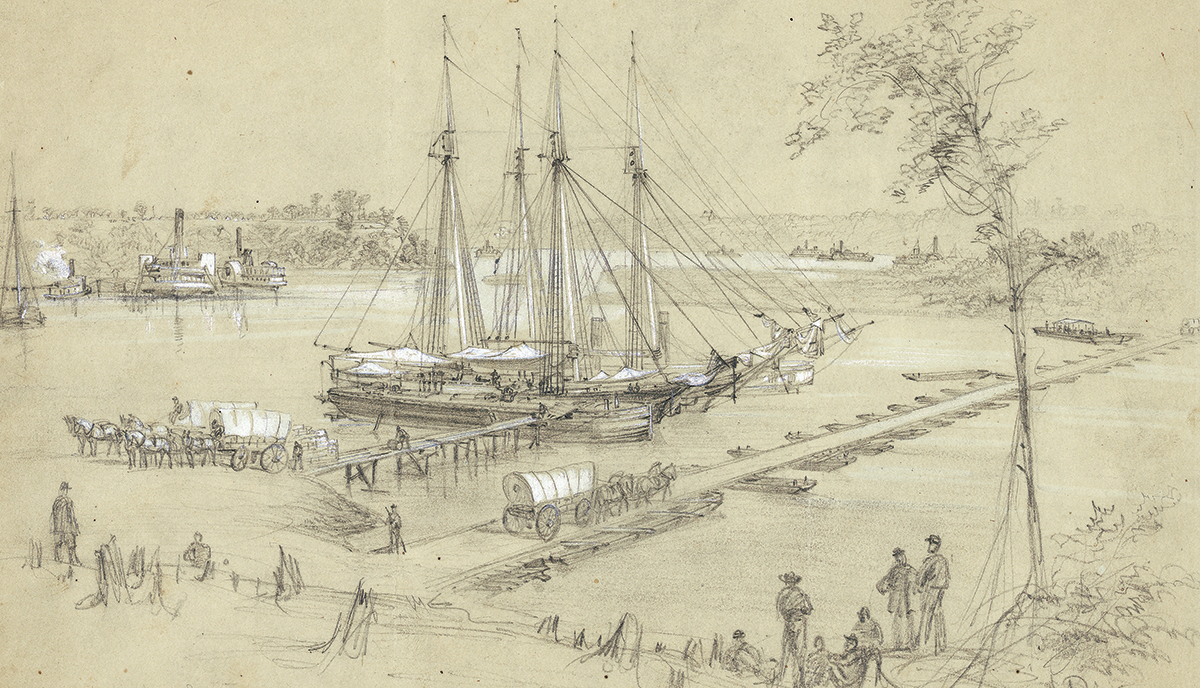

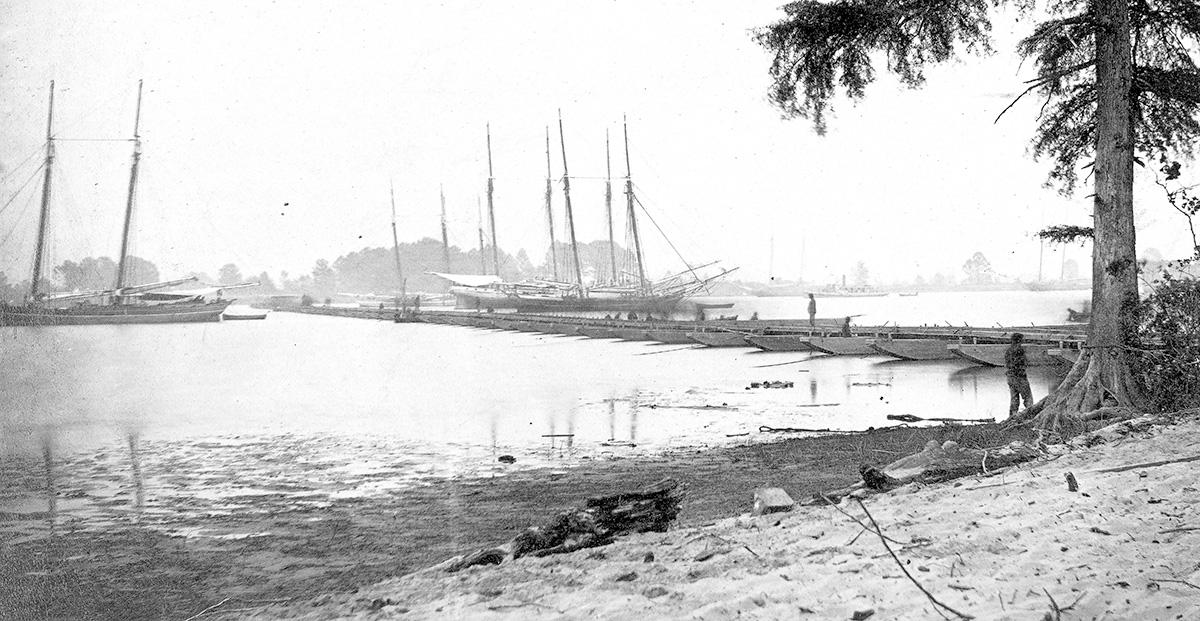

One of the wooden boat trains of the 50th New York Engineers at their camp near

Rappahannock Station, Virginia, shortly before the beginning of the Overland

Campaign

Library of Congress

The brigade’s movement to join McClellan’s army illustrated one of the advantages of pontoniering in the East,

with the theater’s more developed rail system and its numerous navigable waterways. The volunteer engineers

traveled by train from Bristol, Virginia, to Alexandria, where they boarded a steamboat that took them and their

pontoons to Fort Monroe. This arrangement made a long, tedious march overland while encumbered by heavy pontoons

on oversized wagons unnecessary.9

Overland transport, however, could not be avoided entirely. The regular engineers had also moved from the

capital to the peninsula by steamboat, but once both units reached Fort Monroe, they had to unload their bridge

trains and advance toward Yorktown on what was a slow and difficult march “on account of the terrible condition

of the roads.”10

Just getting American forces arrayed before Yorktown required a significant amount of bridging because of

McClellan’s decision to employ siege-like operations to batter the town’s Confederate defenses. Getting the

heavy artillery in position across the many ravines and branches of Wormley Creek kept the engineers busy for

much of the siege. Indeed, while Captain Duane’s small command of regulars supervised the construction of most

of the siege batteries and trenches, Woodbury’s volunteers eventually took charge of most of the road and bridge

work required to get the guns into position. Almost immediately, the formal organization of the army’s six

bridge trains disintegrated as boats and equipment were parceled out in small groups as needed. The engineers

built three pontoon bridges, numerous crib bridges and at least one improvised floating crossing. This variety

became essential in late April when McClellan set aside some seventy pontoon boats to support a planned

amphibious landing. Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin’s division was to land on the opposite shore of the York

River to silence a rebel battery at Gloucester Point that was harassing the American siege works. Although the

original plan became unnecessary when the Confederates abandoned Yorktown, Franklin used the boats to land his

newly established and still provisional VI Corps at West Point, Virginia, about 30 miles upriver.11

Once Yorktown fell to American forces, the Chickahominy River became the Army of the Potomac’s next major

obstacle as it continued its advance on Richmond. This stream flowed southeast through a wide, swampy bottomland

from a point north of the rebel capital until it turned south and emptied into the James River a few miles above

Williamsburg. After the volunteer engineers repaired and reorganized the army’s pontoon trains at White House

Landing, they and the regular pontoniers undertook an enormous amount of bridge work along the Chickahominy,

both before and after the Battle of Fair Oaks in late May and early June. When McClellan retreated to a new base

at Harrison’s Landing on the James during the Seven Days’ Battles, though, his engineers dismantled all their

crossings, abandoning or destroying many of the pontoon boats because they lacked sufficient transportation to

bring them off quickly overland in the presence of a pursuing enemy. Their loss highlights the difficulty of

moving the pontoons rapidly by wagon.12

Underscoring the limits of overland transport, when newly appointed General in Chief Henry W. Halleck ordered

McClellan to return to the Washington area and abandon the peninsula approach to Richmond, the American

engineers and their boats left Virginia the same way they had arrived—by water. Although the engineer troops

themselves were capable of building replacements for the pontoons lost during the retreat to the James and may

have done so at Harrison’s Landing, the Engineer Department in Washington also forwarded some replacements. All

those boats had been stored at Fort Monroe while the army remained along the James. On August 10, the pontoniers

left the camp at Harrison’s Landing for the fort near the river’s mouth. There, they lashed the boats together

into rafts that steamships then towed back upriver to Barrett’s Ferry where the Chickahominy empties into the

James. There, the engineer troops threw a pontoon bridge more than a third of a mile long across the

Chickahominy to expedite the army’s evacuation. Once the bridge served its purpose, the steamboats towed away

rafts of pontoons and carried the engineers back to the vicinity of Washington where they rejoined the army.13

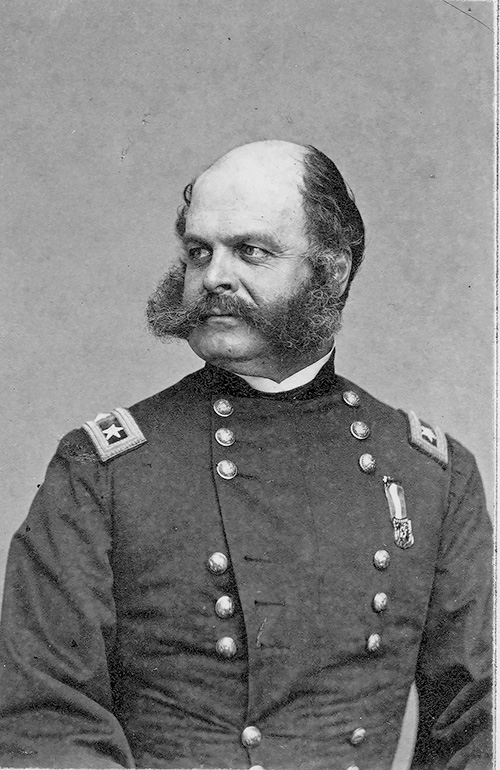

General Burnside

Library of Congress

General Woodbury

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The subsequent Maryland campaign that reached its climax with the Battle of Antietam involved little

pontoniering and few engineer soldiers. By early September, the pontoniers were back at their old encampments in

the capital city, having repaired and reorganized their boat trains while at Aquia Creek south of Washington.

The Volunteer Engineer Brigade remained on duty in the capital until after Antietam, with its soldiers

continuing to build and repair pontoons while simultaneously improving the city’s defenses. The regular

battalion joined McClellan’s army and marched out of Washington on 7 September 1862. Their primary service

before the campaign’s major engagement was improving two fords across Antietam Creek in front of Maj. Gen. Edwin

V. Sumner’s II Corps the day before the battle. They played no role in the fighting, other than guarding the two

improved crossings. Most of the campaign’s bridge building came after the battle.

On 12 September, four companies of the 50th New York Engineers left Washington with a pontoon train to rejoin

the army in the field, and eventually they were ordered to Harpers Ferry to reestablish river crossings that the

rebels had destroyed after capturing the garrison. On the twentieth, they threw the first of five bridges in the

area, this one over the Potomac at Harpers Ferry itself. The Engineer Battalion joined them the next day, and

together they raised and repaired the wooden bateaux that had been scuttled earlier in the campaign. Another

detachment of the 50th New York arrived by rail two days later with more boats brought up from Washington.

Thereafter, the engineers added a second bridge over the Potomac and another nearby over the Shenandoah River.

In late October, they threw two more bridges across the Potomac 15 miles downriver at Berlin (present-day

Brunswick), Maryland. As the engineers commenced these final two crossings almost six weeks after the battle of

Antietam, McClellan finally began returning his army to Virginia, but in part because of these delays,

McClellan’s command tenure was nearly over.14

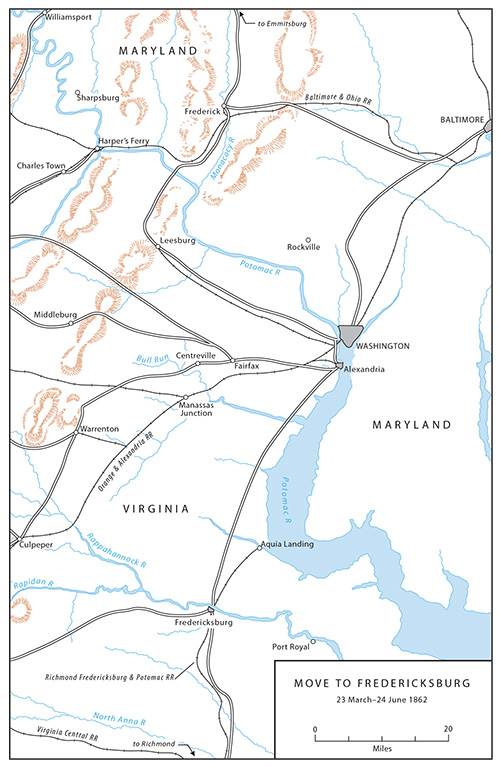

The Fredericksburg Campaign

The Fredericksburg Campaign initiated by the army’s new commander, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, brought the

limits of eastern pontoniering into sharp relief. Shortly before his removal, McClellan had considered a

movement that might take the army through Fredericksburg to bring General Robert E. Lee’s Army of

Northern Virginia to battle by threatening to cut it off from its base at Richmond. Although these

plans were far from concrete, if implemented, McClellan would need the boat trains that were at Harpers Ferry

and Berlin to cross the Rappahannock River just north of Fredericksburg. Consequently, on 6 November he had his

chief engineer, Captain Duane, order General Woodbury of the Engineer Brigade to move the pontoons to

Washington, closer to Fredericksburg. The request, however, was not urgent, so Duane sent it by regular mail

rather than via telegraph. Woodbury did not receive it until 12 November, and Maj. Ira Spaulding of the 50th New

York did not get the first thirty-six boats to the capital for two more days.15

Lieutenant Comstock

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

General Halleck

Library of Congress

Between the order directing the pontoons to Washington on 6 November and Spaulding’s arrival on the fourteenth,

the situation changed. On 8 November, Burnside replaced McClellan and definitively decided to move overland

against the Confederate capital, which required him to cross the Rappa-hannock at Fredericksburg. He planned to

reach Falmouth by the seventeenth, when he would need the bridging materials. After a 12 November meeting with

Quartermaster General Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, General Halleck, and General Herman Haupt of the U.S.

Military Railroads, Burnside incorrectly assumed that all the pontoon equipment was already on the way to the

capital and that Halleck would be able to forward it to Falmouth in time for the planned crossing. Halleck did

order Woodbury to send the pontoons to Aquia Creek, a tributary of the Potomac just a dozen miles from Falmouth.

At this stage, though, with only one train on the road from Berlin to Washington, Woodbury informed Halleck that

the best he could do was to get that one train to Falmouth by the sixteenth or seventeenth while also sending a

second one directly to Falmouth by water. However, the engineer general was still not informed about the

critical need for the boats. It was another two days before Burnside’s chief engineer, Lt. Cyrus B. Comstock,

finally told Woodbury of the urgency. The engineer general later claimed that when he finally knew how important

the movement of the boats was to the upcoming operation, he asked Halleck to delay it for five days to give him

time to move all the pontoons. When Halleck refused to interfere with field operations and postpone Burnside’s

schedule, Woodbury promised to dispatch the boats from Washington immediately, if the quartermaster provided the

necessary horses. The local quartermaster, however, did not deliver the animals until the nineteenth, two days

after the army’s advanced elements reached Falmouth. Once Major Spaulding acquired the horses, he led the trains

out of Washington, but Woodbury failed to tell Spaulding how urgently the army needed its bridging

equipment.16

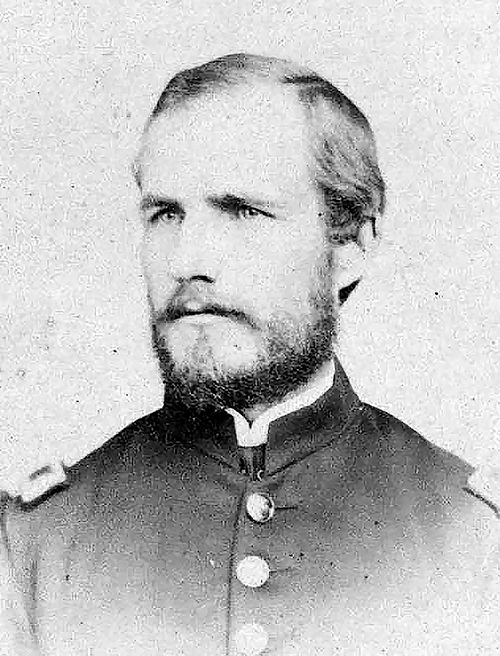

Lieutenant Cross

Library of Congress

Burnside first learned about all the delays on the fourteenth when Comstock spoke to Woodbury, but at that stage

the army commander remained optimistic about maintaining his original schedule and crossing the river on 17

November. The Army of the Potomac departed for the Rappahannock on the fifteenth, but because of his inability

to procure horses to haul the pontoons, Spaulding did not leave Washington for another four days. By that time,

heavy rains had turned the roads to mud, slowing progress to a mere 5 miles per day once he finally had the

boats on the road. Two days out of Alexandria, Spaulding sent fifty-eight pontoons down the Potomac to Belle

Plain just 10 miles from Fredericksburg while he continued with most of the equipment wagons and a few boats

overland. Maj. James Magruder of the 15th New York moved another train via the Potomac from Washington to Belle

Plain on the twenty-second. Again, no one had communicated the urgency of the movement, and the quartermaster at

the landing delayed providing Magruder with the horses he needed to pull his train overland to Falmouth. Because

of all the delays, the first boats did not arrive opposite Fredericksburg until 24 November, a week later than

the original schedule, and it was another three days before the Army of the Potomac had all its bridging

equipment on hand. The extra ten days allowed Lee to concentrate his army on the heights south Fredericksburg, a

move that eventually undermined Burnside’s operations.17

Almost everyone involved with the American movement shared some culpability. Managing all the army’s supporting

components was the new field commander’s job, but Halleck could have aided Burnside’s operations by just

informing the engineers how urgently Burnside needed the pontoons. This was Burnside’s responsibility as army

commander, but the general in chief should have supported him during his transition to army command. Once he was

finally aware of the urgency, General Woodbury compounded the problems by failing to inform his own subordinates

about the importance of getting the bridge equipment to Falmouth. So when quartermaster officers, who were also

unaware of the movement’s urgency, did not immediately supply the draft animals needed to haul the boats,

neither Spaulding nor Magruder demanded prompt action. Overall, poor communication compounded the delays caused

by the logistical problem of moving the large and bulky boats over inadequate roads in bad weather.

This postwar chromolithograph, produced by Thure de Thulstrup for L. Prang & Co.,

depicts the laying of the two upper bridges opposite Fredericksburg before the December 1862 battle. It

also shows, out of sequence, the ferrying of infantrymen across the river to secure the far

bank.

Boston Public Library

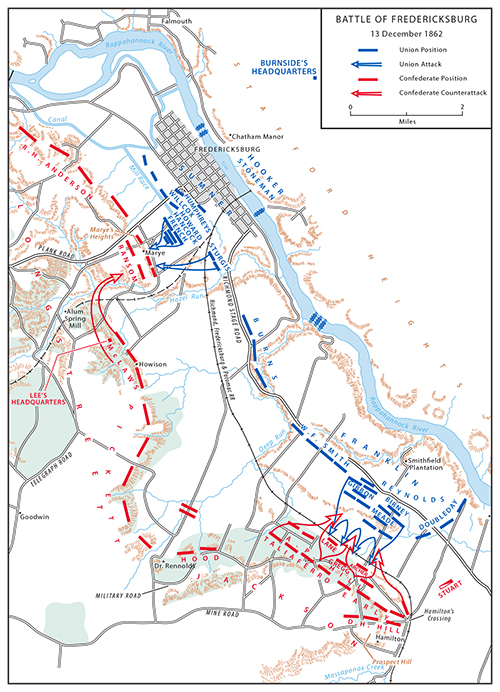

Nevertheless, by 27 November, the bridge trains were at Falmouth where Burnside now confronted Lee’s army

positioned on the ridge south of Fredericksburg. In the changed situation, Burnside contemplated crossing

downriver from the town beyond Lee’s right, but poor roads and alert rebel pickets convinced him to retain his

initial operational concept. The delays created by the miscommunications and the commander’s indecision meant

that by early December, throwing a bridge in front of Fredericksburg required the American engineers to make the

first contested river crossing of the Civil War. In doing so, the pontoniers established a procedure used for

the remainder of the conflict whenever the rebels opposed a crossing. Burnside planned to send the Left Grand

Division of William B. Franklin, now a major general, to make the main attack against the rebel right just

downriver from the town proper. Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner’s Right Grand Division probed the Confederate left,

and Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Center Grand Division stood ready to assist either advance. To support these

plans, the engineers laid six bridges: two upriver near the northwestern corner of Fredericksburg for Sumner’s

Grand Division, one “middle bridge” near the old railroad crossing at the town’s southwestern corner for

Hooker’s troops, and three bridges at Deep Run 2 miles downriver for Franklin’s soldiers.18

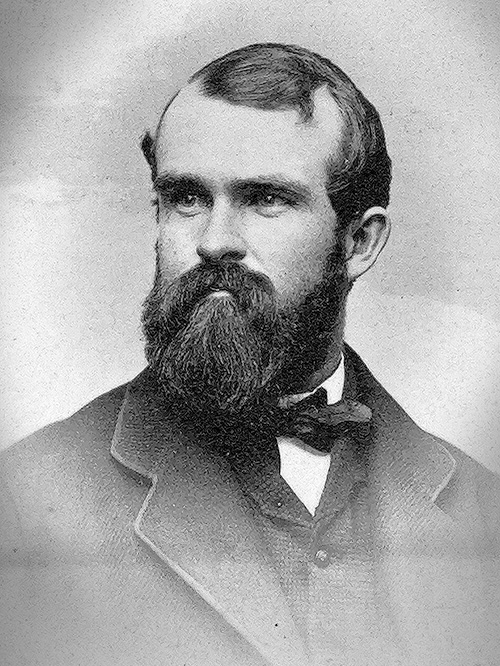

George Ford, shown here as a major in 1865. Three years previously, Ford helped to

supervise the throwing of the upper bridges at Fredericksburg as a captain in the 50th New York

Engineers.

Library of Congress

The Rappahannock was clogged with ice when the engineers began bridging operations in the wee hours of 11

December. At Deep Run, later called Franklin’s Crossing, the pontoniers of the regular battalion and the 15th

New York volunteers unloaded their boats near the 400-foot-wide river. Lt. Henry V. Slosson led a detachment of

volunteers into the water to start the first bridge in this area about 0500. Covered by dark and fog, they met

no opposition until they were placing the final balks. Just as the bridge was almost finished, two rebel

regiments opened fire and wounded six pontoniers. Slightly downstream, the regulars started later and faced

stiffer resistance. A steep embankment required Lt. Charles E. Cross’s detachment to haul the heavy boats by

hand for the last hundred yards. By the time they started the second crossing at Deep Run around 0700, southern

troops had noticed the bridging operations. By 0900, Cross had ten boats in the water and had led a small group

to the far shore to prepare the abutment, when enemy pickets opened fire. They captured two of Cross’s

pontoniers, wounded another, and briefly drove the rest off the unfinished bridge until fire from the engineers’

supporting infantry overcame the rebel pickets. Two hours later, the regulars’ bridge was open. Later that day,

Chief Engineer Comstock ordered the pontoniers to open a third bridge at Deep Run, which Slosson’s New Yorkers

threw with no opposition. By that afternoon, some of Franklin’s infantry had crossed the three spans and secured

the bridgehead.19

General Benham

Library of Congress

Farther upriver immediately across from the town, resistance was much fiercer. The 50th New York began three

bridges directly opposite Fredericksburg around 0300. Capt. James H. McDonald supervised the troops building the

middle bridge, while Capts. George Ford and Wesley Brainerd directed the pontoniers throwing the two upper

bridges. After three hours’ work, the middle bridge and one of the two upper ones were between half and

two-thirds finished and the second upper bridge was about a quarter complete. That was when William E.

Barksdale’s Mississippians opened fire, driving the engineers from their work, wounding Captain McDonald at the

middle bridge and killing Capt. Augustus Perkins at one of the upper crossings. Repeatedly, the officers of the

50th New York led their pontoniers back to work, only to be driven off again. Even the heavy bombardment that

Burnside ordered from U.S. Army artillery on Stafford Heights about noon failed to dislodge the enemy, even

though it devastated the town’s buildings.20

Gilbert Thompson, shown here a month after he mustered out in late 1864 and before

returning to Army of the Potomac headquarters as a civilian topographer.

Library of

Congress

Around 1500, Burnside approved a suggestion from his artillery chief, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, that the

pontoniers ferry infantrymen over the river in their boats to establish a beachhead before continuing the three

bridges directly before Fredericksburg. At the uppermost site, a detachment from the 50th New York led by Lt.

James Robbins carried about 400 soldiers from one Michigan and two Massachusetts regiments over the Rappahannock

in several trips. While Barksdale’s rebels now tangled with the Americans on their side of the river, the

pontoniers returned to their bridge work. Major Spaulding, then in command of the 50th New York, took charge of

the two upper bridges. Half an hour after the infantry crossed, his troops completed the first upper bridge, and

the second was not far behind. A similar chain of events played out at the middle bridge. There, Maj. James

Magruder and his 15th New York pontoniers ferried a hundred soldiers from the 89th Regiment, New York State

Volunteers, over the river. While the infantrymen cleared the rebels from the southern part of town, Magruder’s

troops were able to finish their span by dusk. In addition to three officer casualties, the Volunteer Engineer

Brigade lost six enlisted men killed and forty-one wounded during the day’s operations. The engineers, however,

learned from Hunt’s suggestion and disseminated his idea. For the rest of the war, when pontoniers in any

theater anticipated a contested crossing, they first ferried infantrymen across in their boats to secure a

beachhead. Unfortunately, at Fredericksburg their work earned few dividends. After Burnside’s failed assault on

the fortified enemy position above the town, he retreated across the Rappahannock and had his engineers

dismantle their bridges.21

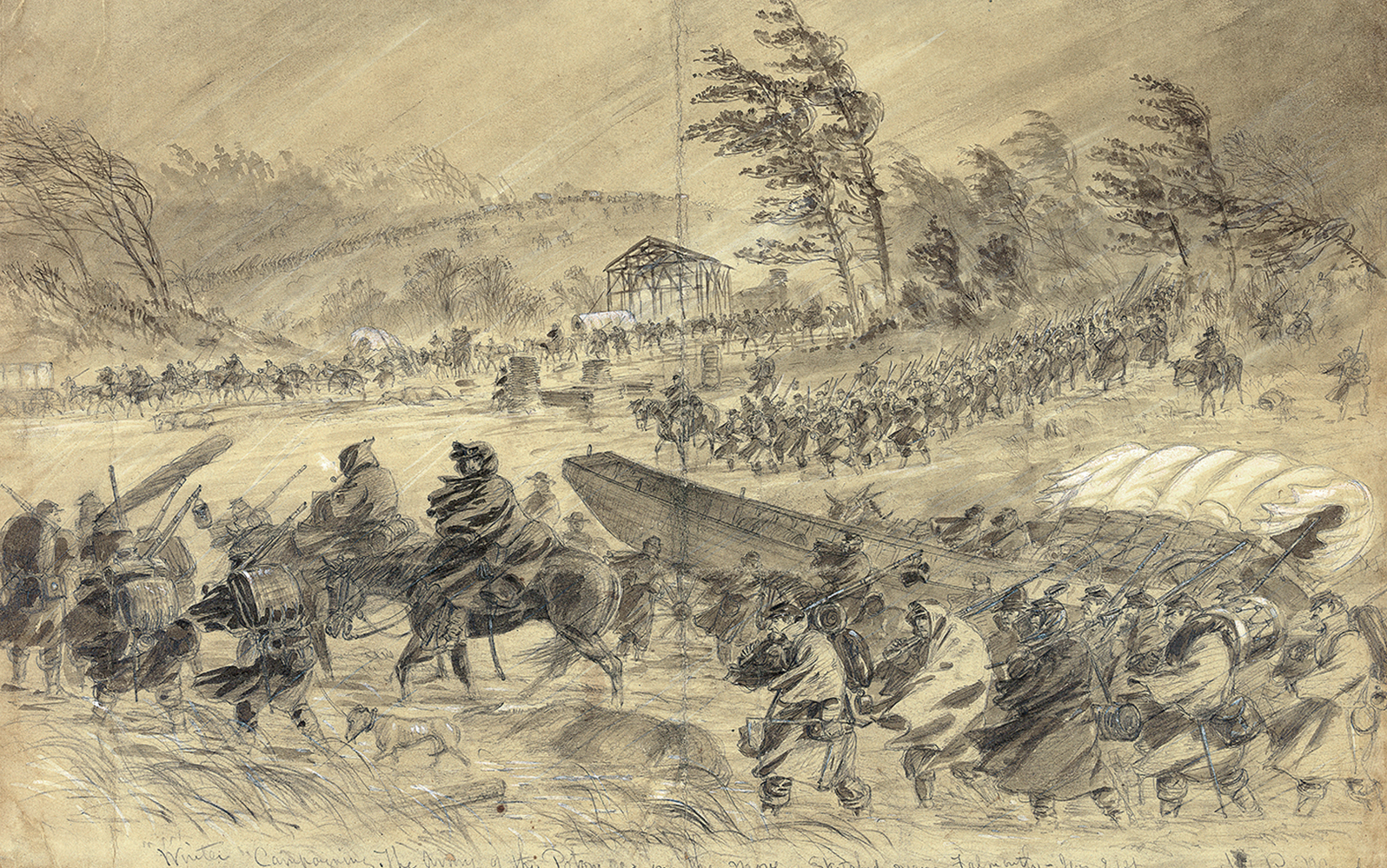

Six weeks later, the army’s engineers facilitated another attempt to dislodge the rebel army at Fredericksburg.

Burnside hoped to turn the rebel left by crossing a pontoon bridge at Banks Ford a few miles upriver. The plan

began well enough. In mid-January, additional pontoon boats arrived from the Washington Engineer Depot, brought

to Belle Plain via the Potomac. Over the next few days, the pontoniers of the Engineer Battalion transported

them overland to the camps at Falmouth. On the twentieth, the turning movement commenced and almost immediately

went awry. As Gilbert Thompson of the regular battalion remembered, “At first the ground was frozen and good

progress was made, but at about dark it began to rain and the ground thawed and broke up. As the darkness

increased, the boat train became separated, a wagon occasionally becoming mired, and delays occurring.” The

heavy rain itself became the enemy, making it virtually impossible to move the pontoon boats to the crossing

site in an episode eventually dubbed the Mud March. The 15th New York fared little better than their regular

comrades as the rain continued for two days. The pontoniers’ heavy wooden boats stuck fast, even when the

engineers removed them from their special wagons and tried to drag them through the mud early on the

twenty-first. A few boats reached Banks Ford but not enough for a bridge, and at midday on 23 January, Burnside

canceled the movement. The engineers spent five days returning the pontoon boats to camp over the abysmal roads.

After this latest failure, Hooker replaced Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac because Burnside had

been unable to produce a success twice because of the inability to get across the Rappahannock when needed.22

This sketch by artist Alfred R. Waud depicts the Army of the Potomac on the move

toward the Rappahannock crossings during General Burnside’s infamous Mud March. Notice the pontoon boat

being manhandled along in the center foreground.

Library of Congress

Learning As They Go

Hooker first reorganized his army, including his engineering arm. He added the regular battalion to the

Volunteer Engineer Brigade, a change that only lasted for his own brief command tenure. He also replaced

Woodbury in brigade command with Henry W. Benham, another regular engineer with a volunteer brigadier’s

commission. Benham had earned a reputation as a less than competent commander in 1862 when he launched an unwise

and unsuccessful assault at the Battle of Secessionville below Charleston, South Carolina. He performed so

poorly that the War Department revoked his volunteer commission that August and did not restore it until

February 1863. Rumors about insobriety also plagued Benham, and his service in charge of Hooker’s engineers only

added to them. When the pontoniers threw the first bridge of the Chancellorsville Campaign in late April, one of

the regular engineers recorded a few days afterward that “To his dishonor, General Benham was tumbling

drunk.” Even though he formally retained brigade command after this episode, his drinking may

explain why Benham spent most of the war after Chancellorsville superintending the Washington Engineer Depot,

while the senior volunteer engineer led the brigade in the field.23

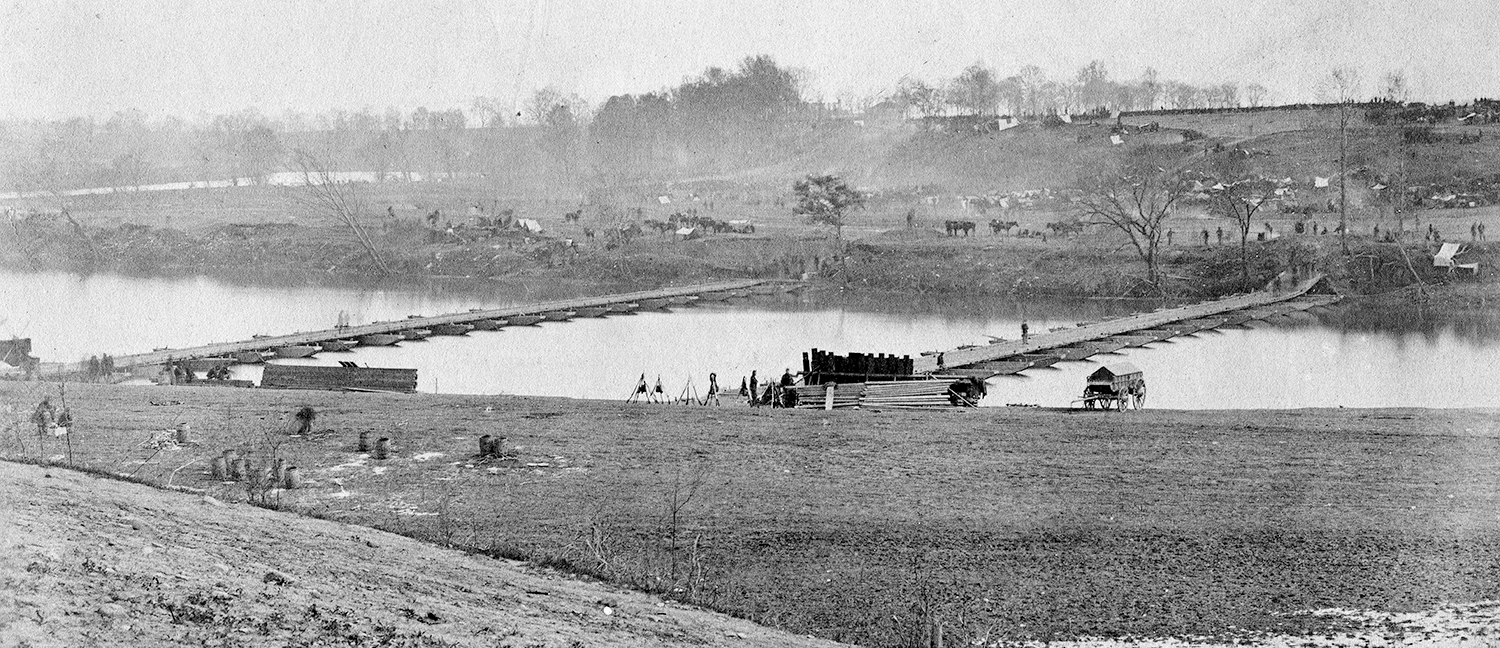

This pontoon bridge supported General Hooker’s Chancellorsville Campaign as part of

the feint mounted against Lee at Fredericksburg. During its construction, Brig. Gen. Henry W. Benham

also demonstrated his insobriety.

Library of Congress

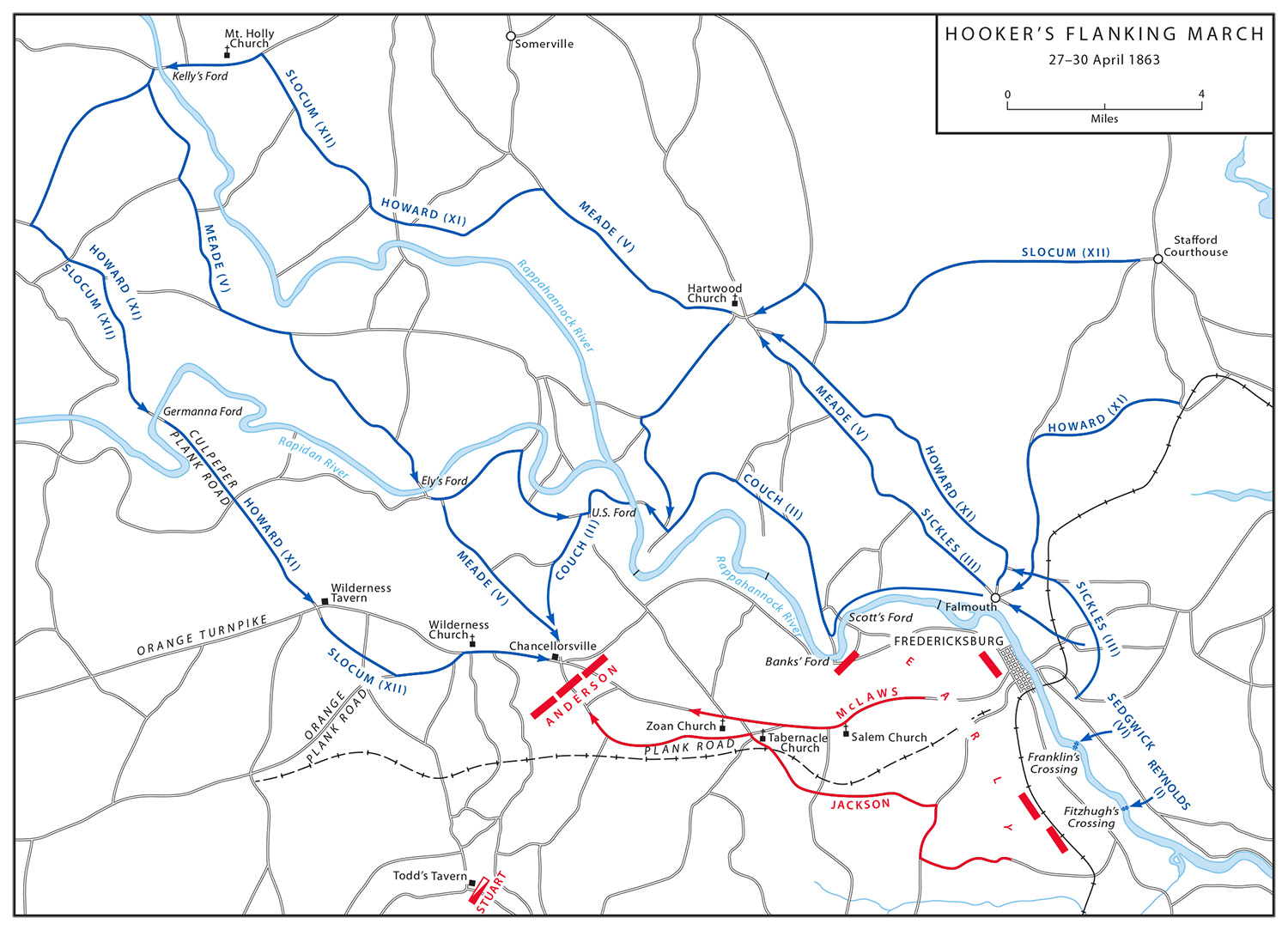

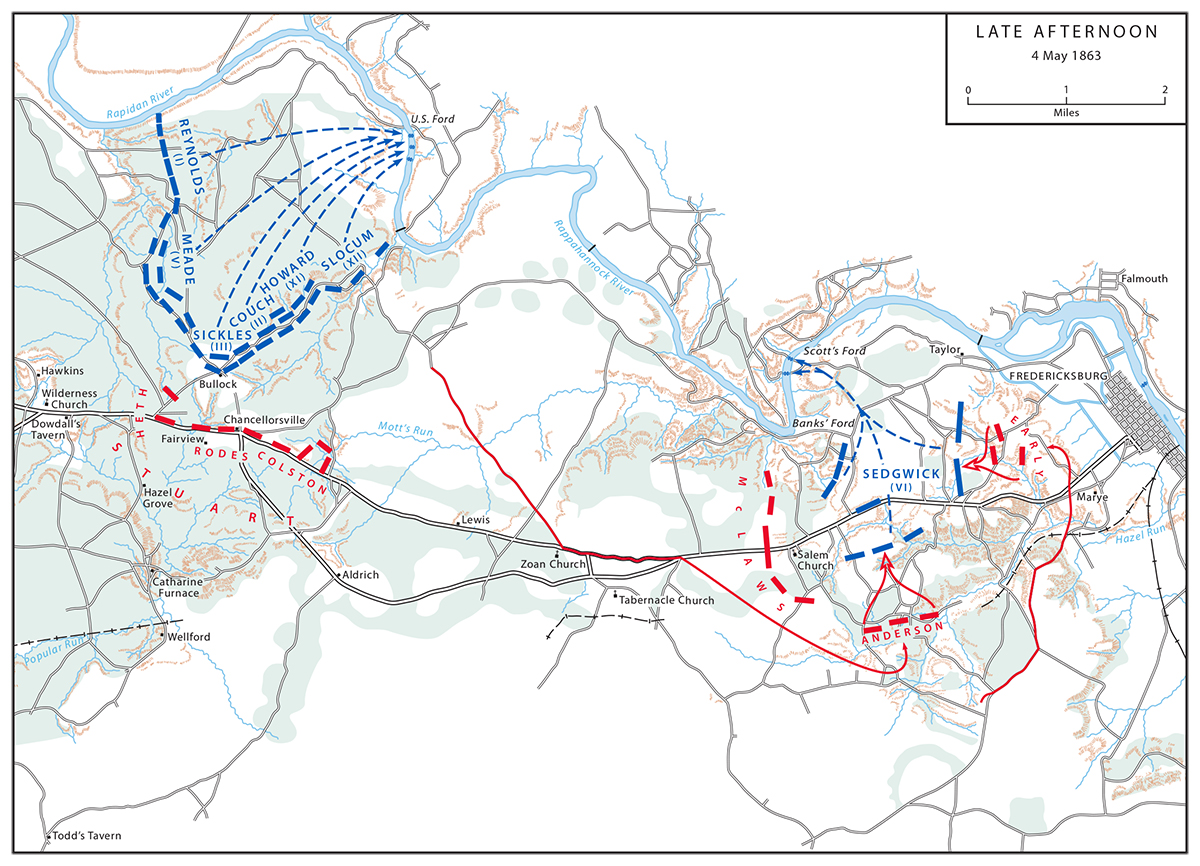

Despite his poor choice for Engineer Brigade leadership, Hooker’s campaign plans had great potential. He

intended for the V, XI, and XII Corps, led by George G. Meade, Oliver O. Howard, and Henry W. Slocum,

respectively, to turn Lee’s left flank via Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahannock, 25 miles northwest of

Fredericksburg, while John F. Reynolds’s and John Sedgwick’s I and VI Corps feinted directly against the town

itself. Hooker’s opening movements succeeded in part because of his pontoniers. Over the last three days of

April, they had laid eight pontoon bridges over the river. Five supported the feint at Fredericksburg: three at

Franklin’s Crossing and two about a mile and a half further downstream. The main flanking force marched over a

pontoon crossing at Kelly’s Ford, and two more spans at United States Ford, about halfway between Falmouth and

Kelly’s Ford. After Hooker lost the battle at Chancellorsville, the engineers threw six more spans for the

American withdrawal: one at United States Ford, two at Banks' Ford, and three at Fredericksburg. Some of

these bridging operations are instructive.

A detachment of volunteer engineers from the 15th New York threw a canvas pontoon bridge at Kelly’s Ford for the

main flanking force on 28 April. Two factors contributed to their rapid success. A nearby railroad ensured their

timely arrival. The detachment traveled from the Engineer Depot in Washington to Bealeton Station, just 5 miles

from the ford, on the Orange and Alexandria line, leaving only a short overland trip for the bulky pontoons. In

addition, an infantry brigade from the XI Corps secured the bridgehead just before the pontoniers went to work.

The infantrymen had been in place for a couple of weeks and previously had established a soldier’s truce with

rebel pickets across the Rappahannock. When the engineers ferried the soldiers over the river late on the

twenty-eighth, it caught the rebels off guard, and they quickly withdrew. By 2230 that night, the bridge was

open.24

The construction of these bridges at the start of the Gettysburg Campaign exacted

several casualties from the engineers, including Capt. Charles E. Cross, the commander of Company B,

U.S. Engineer Battalion.

Library of Congress

South of town at Franklin’s Crossing, the regular and volunteer pontoniers laid five spans, having also learned

from their Fredericksburg experiences to secure the opposite shore in advance. The Engineer Battalion threw the

bridge at Franklin’s Crossing under Benham’s alleged supervision. The general, as one pontonier put it, became

“mulfathomed with drink” as the soldiers conducted the operation over the night of 28–29 April. The

engineers first took soldiers across the river in their pontoon boats while under fire from rebel pickets who

may have been alerted by Benham’s drunken shouting. Nevertheless, after four trips the pontoniers had landed

enough infantrymen to end enemy resistance. By 0800 that morning, they had a bridge in place for Sedgwick’s

feint against Fredericksburg. Later, after Hooker had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory, the battalion’s

soldiers relocated this bridge using the river itself as a conveyance. Although the volunteer detachment nearby

removed their crossing from the Rappahannock entirely and hauled the pontoons overland to a new position, the

regular pontoniers only partially dismantled their bridge at Franklin’s Crossing. They broke it down into rafts

that consisted of four pontoon boats each, rowed the rafts upstream, and reassembled them into a bridge near the

southeastern corner of Fredericksburg.25

Despite the regular pontoniers’ efforts at Franklin’s Crossing and the town proper, the volunteer engineers’

work at United States Ford saved Hooker’s army after the defeat at Chancellorsville. Inside a fortified

bridgehead laid out by the army’s chief engineer, both New York engineer regiments struggled to prepare three

crossings for the army’s withdrawal. Just as they finished the approach roads, it started raining in sheets.

Within hours, the river rose 6 feet, and the current accelerated enough to threaten the bridges. The uppermost

span took most of the damage, so the pontoniers dismantled it and used its pontoons to strengthen the other two.

By midnight, they had completed the two remaining bridges, allowing the army to return to the safety of its camp

at Falmouth, but it did not remain for long.26

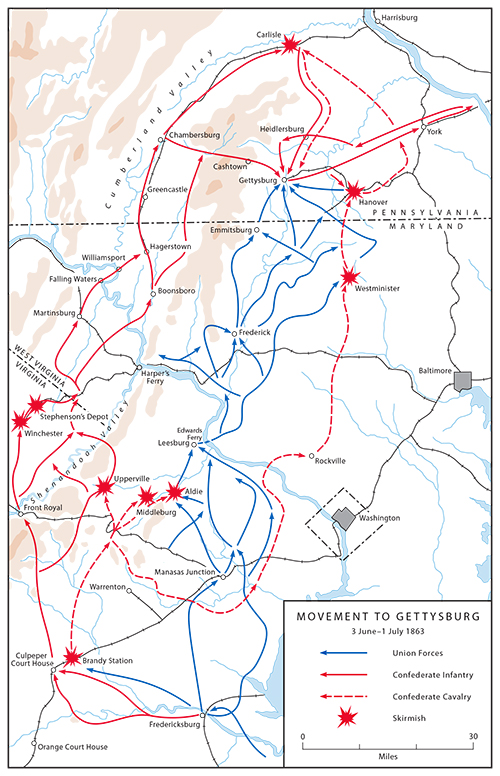

When Lee marched north on the Gettysburg campaign, the American engineers continued their work to enable the

Army of the Potomac’s pursuit. They threw nine bridges over three different rivers in this campaign, but the

rebels only contested the first. When Hooker first learned that Lee’s army had begun moving in early June, he

ordered Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick to conduct a reconnaissance toward the rebel forces still at Fredericksburg. To

enable Sedgwick’s advance, the regular engineer battalion and a detachment of volunteers from the 50th New York,

working together on the same span for the first time, bridged Franklin’s Crossing yet again on the afternoon of

5 June. Based on recent experience, they had planned to send troops over first to secure the bridgehead, but a

small, fortified Confederate position on the opposite shore made the ferrying operation extremely hazardous. The

rebels opened fire when the pontoniers moved their wagons to the riverbank that afternoon, inflicting several

casualties before the engineers even reached the Rappahannock. The much beloved commander of the regular

battalion’s Company B, the recently promoted Capt. Charles E. Cross, fell among his soldiers, shot through the

head just as he stepped into one of the first pontoons intended to cross the river. Once the engineers managed

to get the infantrymen across, the soldiers secured the bridgehead, allowing the engineers to build the bridge.

Sedgwick led part of his corps across, but found his path blocked by A. P. Hill’s troops. Sedgwick returned a

few days later, and the pontoniers dismantled the span.27

The rest of the campaign’s crossings were uncontested, but the means of transportation that the engineers

employed for their boats is instructive. On 12 June, the regular engineers took their pontoons to Aquia Creek.

There, the pontoniers boarded the Sylvan Shore, a steamship that took a raft of sixteen pontoon boats

in tow before heading north to the mouth of the Occoquan River. There the pontoniers disembarked and rowed their

boats further up the Occoquan to throw a bridge of fourteen boats. The next morning, after the army had crossed

the small span, the regular engineers dismantled it and rowed the pontoons downriver to Colchester Ferry where a

detachment from the 50th New York met them with more boats brought up by water from Aquia Creek. Together, the

two groups spanned the Occoquan again with a bridge for the army’s artillery and its cattle train. The

volunteers left after helping to open the bridge, and after the trains had crossed, the battalion pontoniers

dismantled the span late on 16 June, tied the boats into rafts, and took them to Edwards Ferry on the Potomac

through the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. At the ferry, they met another detachment of the 50th New York bringing

up more boats on the Potomac from the Washington Engineer Depot. Using sixty-four pontoons as well as three crib

trestles, the engineers built a bridge more than 1,300 feet long to get the army over the Potomac just below

Frederick, Maryland. After the volunteers floated more boats up through the Chesapeake and Ohio, the regulars

threw another, smaller span over the nearby Goose Creek to provide easier access to the main bridge, and a few

days later the volunteers added another crossing over the Potomac to speed the army’s march north. By 27 June,

the entire Army of the Potomac was in Maryland, and the pontoniers dismantled all the Edwards Ferry crossings.

The volunteer engineers took most of the boats back to the Washington Depot via the canal while the regulars

rushed after the army with their own bridge train, though they did not participate in the climactic fight at

Gettysburg or conduct any more bridging beforehand. Indeed, when the Engineer Battalion reached army

headquarters at Taneytown, Maryland, on 1 July, its pontoon train returned to the Washington Engineer Depot by

wagon.28

The engineers’ ability to use the rivers and canals of northeastern Virginia may explain the eastern pontoniers’

preference for the heavier wooden pontoons. With water or rail transport more easily available, the heavier,

more durable boats that could remain in the water longer made a sensible choice. In Virginia, the engineers

continued to use rivers and rail lines whenever possible. For instance, as the Army of the Potomac prepared to

return to Virginia after Gettysburg, the regular pontoniers raised and repaired some scuttled boats at Harpers

Ferry and carried them down the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Berlin, Maryland, where they met another boat train

coming up the waterway. With the help of the volunteer engineers who brought these additional boats, they put

three bridges over the Potomac to carry the army back to Virginia.29

Shortly thereafter, bridging operations resumed along the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Lee withdrew south

beyond the Rapidan after the Gettysburg campaign, and Meade followed to Culpeper. During Lee’s thwarted Bristoe

Station offensive, when he moved around the Federal right, Meade pulled back from Culpeper and marched north in

October. The American engineers pulled up their bridges and followed the army, using the Orange and Alexandria

Railroad to move their pontoons whenever possible. Once the II Corps of Meade’s army defeated the rebels at

Bristoe Station, the Army of the Potomac returned to its position north of the Rapidan. In the Mine Run Campaign

of late November, when Meade tried unsuccessfully to turn Lee’s left by crossing the Rapidan at Jacob’s and

Kelly’s Fords, wagons were the pontoniers’ only option for hauling their bulky equipment to the crossing points.

After the year’s final movement, some of the pontoon bridges over the Rappahannock behind the army’s camp at

Brandy Station remained in place all winter, an option made possible by the more durable wooden bateaux.30

A New System for the Overland Campaign

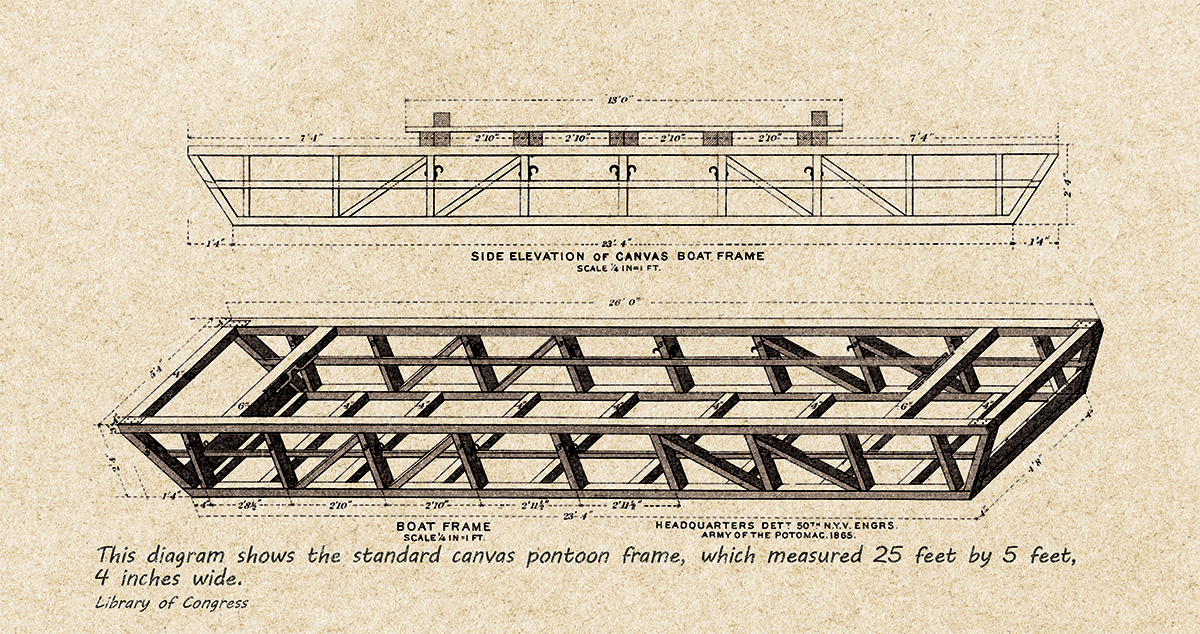

The Army had not neglected canvas boats in the Eastern Theater, but in the war’s early years, the lighter-weight

pontoons had drawbacks and had failed to perform well. In September 1863, Maj. Israel Woodruff at the Engineer

Department sent William P. Trowbridge orders for the New York Engineer Agency to construct a canvas train for

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s western army, adding that the canvas pontoons Trowbridge’s agency had earlier

provided for the Army of the Potomac were defective. Cyrus B. Comstock, who had been promoted to captain and was

now General Grant’s chief engineer, had complained that the earlier pontoons’ transoms, which were supposed to

strengthen the wooden boat frames, tended to split when carrying heavy loads. Comstock’s complaint led the

Engineer Department in Washington to seek the opinions of field engineers about boat design. In December 1863

and again in January and March of the next year, Maj. John D. Kurtz at department headquarters asked engineers

in the field for input on pontoon design. At the same time, James. C. Duane, now a major serving as the Army of

the Potomac’s chief engineer, designed a new canvas frame. His model was 5 feet shorter than the older one,

making it more maneuverable in tight spaces, even without the geared wagons. Duane’s design was still as wide as

previous models, so it could support the same length of bridge with the same number of boats. He even achieved a

buoyancy equal to the wooden bateaux, allowing his new canvas boats to bear heavy loads. Although Duane improved

the canvas pontoons, Col. William H. Pettes of the 50th New York developed improved pontoon and chess wagons for

all the trains, and both Duane and Pettes finished their new bridging equipment by the time Grant opened the

Overland Campaign in early May.31

Major Duane also overhauled the Army of the Potomac’s entire engineering organization for that campaign. Under

his directions, the regular battalion focused on field fortifications, roadwork, and small temporary bridges,

whereas the 50th New York, commanded in the field by Ira Spaulding who had risen in rank to lieutenant colonel,

managed all the bridge trains, both wooden and canvas. Duane, however, retained ultimate control of the trains

to provide unified direction. He split the New York engineer regiment into four battalions. Duane detailed three

of these, each with a wooden train, to specific corps. The first battalion under Maj. Wesley Brainerd served

with the II Corps. Maj. Edmund O. Beers’s second battalion joined the VI Corps, and Capt. James H. McDonald

commanded the third battalion in support of the V Corps. The fourth battalion, led by Colonel Spaulding, carried

a canvas train and served as the reserve. At Duane’s direction, the reserve train with its lighter and more

maneuverable boats moved in front of the army’s leading column and built its initial crossings to keep the army

moving. When the first of the more durable wooden trains arrived at any given stream, the heavier bridge

replaced the less durable canvas boats, and the reserve battalion pulled up their span and rushed to the head of

the column to be ready for the next crossing. Duane’s new procedures, combined with the numerous rivers in

Virginia, led to an astonishing number of bridges over the six weeks of the Overland campaign. From 29 April,

when the Empire State pontoniers laid the campaign’s first span, through 23 June, they built thirty-eight

separate crossings, ranging from 40 to 400 feet in length.32

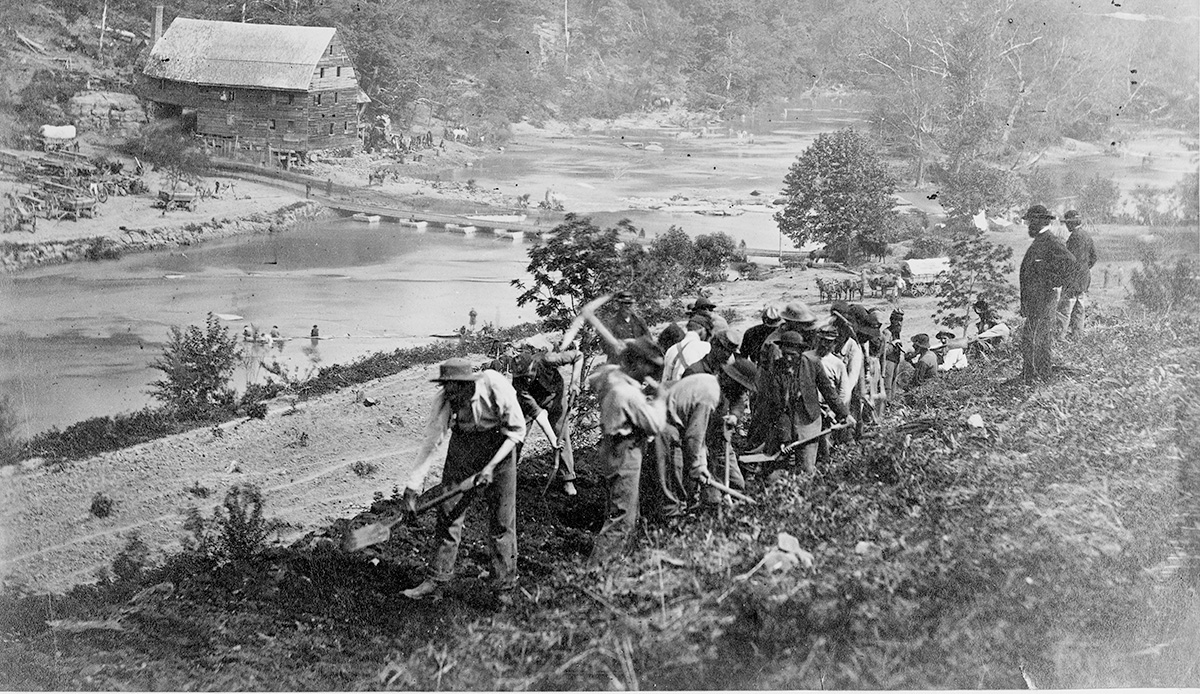

Soldiers from the 50th New York Engineers construct a road on the south bank of North

Anna River near Jericho Mills, Virginia.

Library of Congress

Duane tested his new pontoniering equipment and organization near the campaign’s start. As Grant positioned his

forces to commence operations, on 29 April, Lt. Mahlon B. Folwell supervised a detachment of the 50th New York’s

fourth battalion as it laid a bridge at Kelly’s Ford using the new canvas pontoons to cross Brig. Gen. David M.

Gregg’s cavalry division over the river. After their success laying this early span with the new boats, the

engineers tested Duane’s new procedures as the campaign began in earnest when the Army of the Potomac crossed

the Rapidan. Lieutenant Folwell’s canvas train reached Ely’s Ford with Gregg’s cavalry at daylight on 4 May.

This was one of three crossing sites for Grant’s forces as they made their first attempt to outflank the

Army of Northern Virginia that spring in a maneuver that culminated in the Battle of the Wilderness the

next day. On the fourth, Folwell’s pontoniers threw their canvas bridge while the troopers forded the river. As

soon as the engineers finished, the II Corps appeared and began its crossing. Shortly thereafter, Major

Brainerd’s battalion, marching with the II Corps, arrived on site and laid its wooden bridge. By 0915, the

wooden pontoon crossing opened, and the II Corps shifted to it, allowing Folwell’s pontoniers to pull up their

canvas boats and return to the front of the column. The II Corps never paused.

This is the crossing that Captain Van Brocklin threw over the North Anna River with

his reserve battalion canvas train on 23 May 1864.

Library of Congress

Similar operations were repeated throughout the campaign as Grant continued crossing the region’s rivers in his

attempts to maneuver the Army of the Potomac around Lee’s right or bring it to battle on open terrain. Duane’s

procedures continued to work well as the army maneuvered, and he also employed a similar approach whenever the

lighter-weight pontoons were needed for more mobile operations elsewhere, as was the case at Jericho Mills along

the North Anna River in late May. On the twenty-third, Capt. Martin Van Brocklin’s detachment of the reserve

battalion built a canvas bridge there that allowed Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps to establish a

lodgment on the south side of the river during the first day of the Battle of North Anna. Three days later,

after the inconclusive engagement ended and the turning movement resumed, Major Beers’s volunteer battalion

replaced this canvas bridge with a wooden one so Van Brocklin’s more mobile train could support Maj. Gen. Philip

H. Sheridan’s cavalry corps as it moved against the Virginia Central Railroad to cut Richmond’s western supply

lines.33

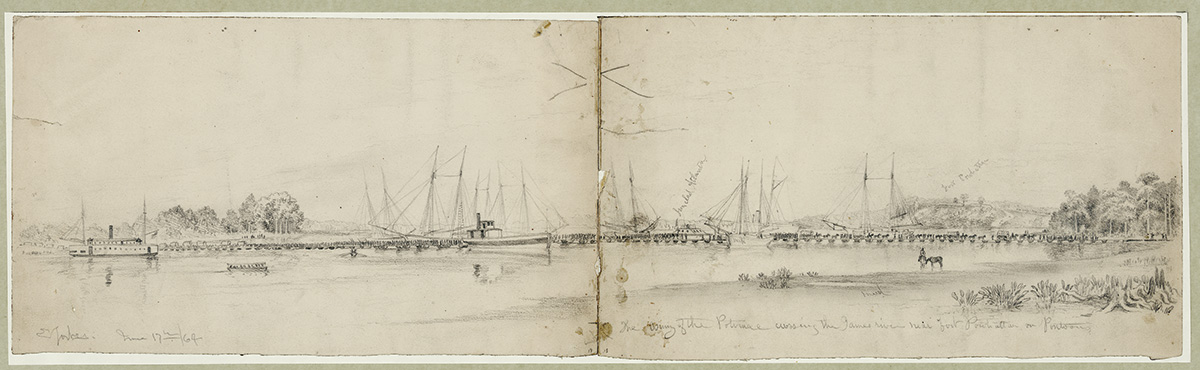

This July 1864 sketch by Alfred R. Waud shows the 1st New York Engineers’ pontoon

bridge at Point of Rocks on the Appomattox. They later disassembled the bridge and sent the boats

downriver to aid in the effort to get the Army of the Potomac across the James

River.

Library of Congress

As the Overland Campaign devolved into a stalemate after the Battle of Cold Harbor, Grant adopted a course that

both redefined the war in the Eastern Theater and relied on his pontoniers for its success. He abandoned his

efforts to isolate and defeat Lee’s army north of Richmond, operating from a direction that allowed his army to

also shield Washington. Instead, Grant opted to throw his army over the James River and seize Petersburg.

Located about 20 miles south of Richmond, this city contained several rail lines critical to Confederate

logistics; if Grant severed these lines, it would isolate the rebel capital and make it vulnerable to capture,

which could deprive Lee of his army’s base. To move against Petersburg, though, the American engineers had to

lay the longest pontoon bridge of the entire war, despite difficulties marshalling their equipment. Grant

intended for Meade’s army to cross the James at Weyanoke Point. There the river narrowed to about 2,000 feet,

which was still a considerable distance for a temporary floating bridge. Moreover, as the channel narrowed, the

current accelerated, creating additional complications for the engineers who already had to deal with the

river’s regular 4-foot tidal change in depth. Creating more difficulties, the Army of the Potomac’s entire

pontoon train was required to get its troops over the Chickahominy and to Weyanoke Point on the James’s north

bank. Therefore, Grant needed the assistance of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James, but the

required cooperation between the two armies was hampered by an unfortunate decision. On 6 June, Grant’s

aide-de-camp, the engineer Cyrus B. Comstock, had told Butler that the commanding general intended to cross the

James soon. Just four days later, one of Butler’s staff officers sent all of his army’s pontoon equipment 35

miles downriver to Fort Monroe for storage.34

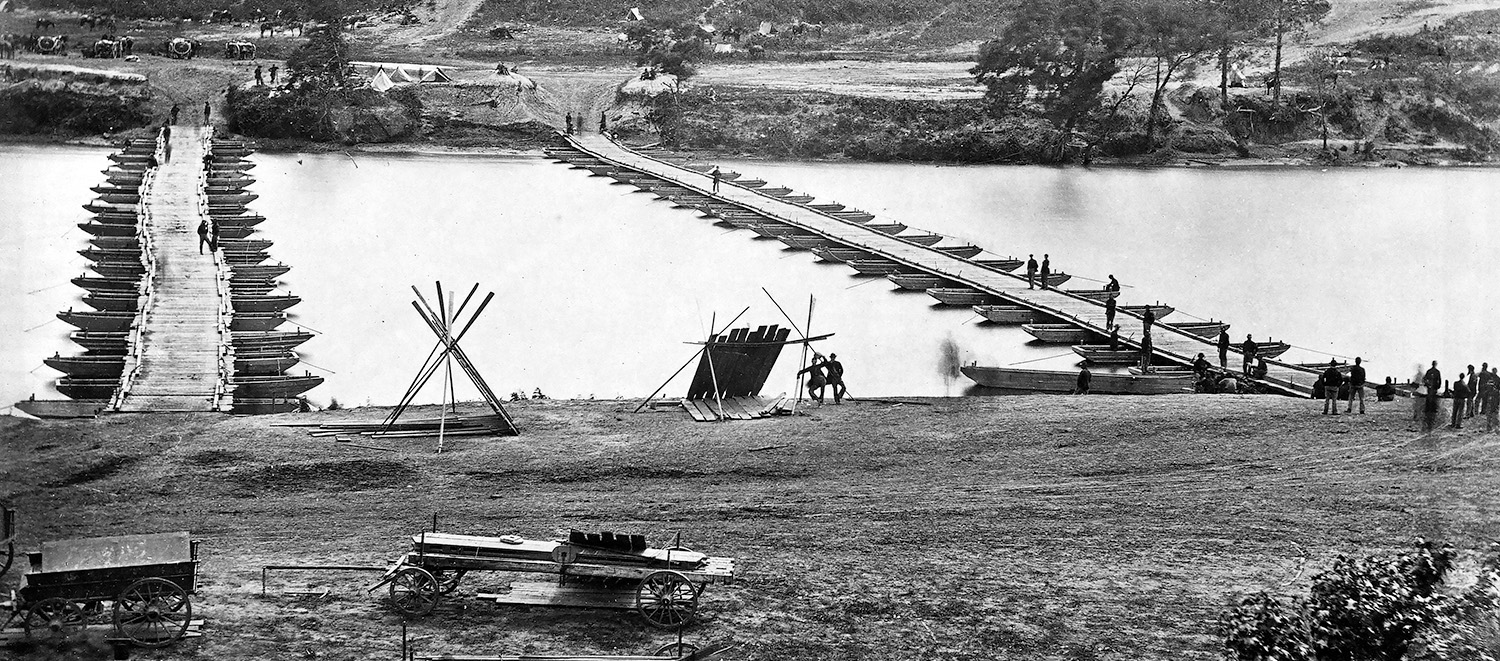

With boats in the water (center right) not attached to the main structure and

soldiers clearly working atop the span, this photograph may show engineers constructing the pontoon

crossing over the James River for Grant’s move against Petersburg in June

1864.

Library of Congress

Fortunately, the ease of moving pontoons over the rivers themselves prevented this from becoming a fatal

blunder. On 12 and 13 June, Grant ordered Butler to send all his available boats to Weyanoke Point for the James

River bridge. The pontoniers of Butler’s 1st Regiment, New York State Volunteer Engineer Corps, immediately

dispatched some of their equipment, dismantling a bridge at Point of Rocks on the Appomattox River and towing

them 25 miles down the Appomattox and James to Weyanoke Point. At Fort Monroe, Brig. Gen. Henry W. Benham of the

Volunteer Engineer Brigade received Grant’s orders and put two volunteer captains, Timothy Lubey of the 15th New

York and James Robbins of the 50th, in charge of getting the pontoons stored at the fort back upriver. In an

eerie similarity to the Fredericksburg crossings two years earlier, Benham failed to communicate the urgency of

the operation to Lubey and Robbins. So when a detachment of the 1st New York Engineers finished the northern

approach road for the James River bridge as the Army of the Potomac approached the crossing site on the morning

of 14 June, the pontoons had not yet arrived. Butler’s chief engineer, Godfrey Weitzel was on site supervising

the work, and he sent a boat downriver to find the pontoons. The two volunteer captains, being unaware of the

importance of their assignment, had decided to wait for the tide to come in to ease their trip up the James.

Informed of the urgency, they immediately set out and arrived at Weyanoke Point by noon. When Major Duane

subsequently arrived with two companies of the Army of the Potomac’s regular engineer battalion, he took charge

of the operation.35

The completed bridge over the James in the late summer of 1864. This photograph also

shows the heavy vessels used to stabilize it against the river’s strong current and tidal changes.

Library of Congress

Work on the bridge accelerated after Duane and his pontoniers appeared. Even after receiving the pontoons, the

1st New York had not accomplished much, but around 1600, Capt. George H. Mendell’s regulars built a trestle out

to deeper water, then crossed to the southern shore, and began laying pontoons on the far side. Three companies

of the 15th and 50th New York arrived about the same time and started placing boats from the new northern

abutment. Benham himself arrived from Fort Monroe and assumed command of the operation around 1700, and by 2300

only 100 feet in the middle of the river remained unbridged. Around midnight the engineers filled this final gap

with a removable draw to allow river traffic to pass. To stabilize the bridge in the face of the tides and rapid

current, the pontoniers anchored it with heavy boats both up- and downriver. Ultimately, the engineers used 101

pontoons to build a 1,980-foot bridge over the James that also included about 200 feet of trestlework. It was,

and still is, the longest pontoon bridge ever thrown by the American Army. The sturdy wooden bateaux allowed the

engineers to build a crossing used by one infantry corps, a division of another corps, and the Army of the

Potomac’s entire supply train, including 5,000 wagons and 3,000 head of cattle. On 18 June, with the army safely

south of the James, the engineers dismantled the bridge. Without the crucial logistical support it enabled,

however, the Army of the Potomac would have been incapable of threatening Petersburg and, after nearly a year of

siege-like operations, cutting this vital rebel supply line. Strikingly, the delays imposed on the James River

bridging operation by poor judgment and miscommunications were quickly rectified by the engineers, and had

minimal operational impact because at the James the engineers enjoyed the benefit of water transport to the

crossing point.36

This illustration by artist Edwin Forbes shows components of the army as they

crossed the James on the engineers’ pontoon bridge on their way to Petersburg.

Library of Congress

Conclusion

The engineers continued their pontoniering efforts in the East until the final surrender of Lee’s army, but by

the time they dismantled the James River bridge, the final pontoniering patterns were set. The war’s first

contested crossing at Fredericksburg had taught them to secure the opposite shore before attempting to deploy a

bridge, a lesson almost uniformly applied in every theater for the rest of the war. They had also learned how to

best organize their trains for operations in the East, with heavier but sturdier wooden pontoons for bridges of

greater length and duration, while using the lighter and more maneuverable canvas boats in the advance to

maintain forward movement and prevent delays. The many rivers and railroads in the Eastern Theater allowed the

engineers to continue their primary reliance on the heavier wooden craft by providing reliable alternatives to

overland transport much of the time. Of course, they continued to use wagons when lacking other options, but

Fredericksburg and the subsequent Mud March had made clear that even the relatively better roads in the East

were not sufficient for the heavy wooden boats under extreme weather conditions. A similar process of experience

and pontoon experimentation in the Western Theater led to an almost universal preference for lighter-weight and

more mobile options because of the sparser infrastructure, but in the East the prevalence of rivers and rails

allowed the wooden bateaux to bear the heaviest burdens of military bridging.37

A pontoon bridge under construction at Belle Plain Landing,

Virgina

Library of Congress

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the Corps of Engineers Office of History, and Matthew T. Pearcy of that office, for supporting

the larger research project from which this article evolved and for permission to share some of the findings of

that project here.

Notes

1.Philip Lewis Shiman, “Engineering Sherman’s March: Army

Engineers and the Management of Modern War, 1862–1865” (PhD diss., Duke University, 1991), 152–53, 273–74.

2.Mark A. Smith, “The Politics of Military Professionalism:

The Engineer Company and the Political Activities of the Antebellum U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,”

Journal of Military History 80,no. 2 (Apr 2016): 361–67.

3.. Ltr, J. D. Kurtz to G. W. Cullum, 8 Apr 1854, Letters

Sent by the Chief of Engineers to Engineer Officers 1815–1869, 40 vols., National Archives Microfilm

Publication T1255, 20 rolls, Record Group (RG) 77, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington,

DC (NAB) (cited hereinafter as T1255), roll 11, 22:108; Ltr, J. G. Totten to A. J. Donelson, 16 Jun 1857,

T1255, roll 14, 27:195–96, 206.

4. J.C. Duane, Henry L. Abbot, and William E. Merrill,

Organization of the Bridge Equipage of the United States Army, with Directions for the Construction of

Military Bridges (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1870), 9–13; “Engineer

Equipment,” in Francis A. Lord, Civil War Collector’s Encyclopedia: Arms, Uniforms, and Equipment of the

Union and Confederacy (New York: Castle, 1963), 91, 93; Shiman, “Engineering Sherman’s March,” 57;

Ltr, R. E. DeRussy to J.C. Duane, 12 Apr 1859, T1255, roll 15, 30:172; H. G. Wright to J. C. Duane, 12

December 1859, T1255, roll 16, 31:34; Ed Malles, ed., Bridge Building in Wartime: Col. Wesley Brainerd’s

Memoir of the 50th New York Volunteer Engineers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997),

279–80, 386n7; Richard Delafield, “Report of the Chief Engineer,” 30 Oct 1865, H. Exec. Doc. No. 1, 39th

Cong, 1st Sess., 2:962; William W. Loughlin, “Detached Service,” in History of the Ninety-Sixth Regiment

Illinois Volunteer Infantry, ed. Charles A. Partridge (Chicago: Brown, Pettibone, 1887), 630.

5.Ltrs, J. G. Totten to Q. A. Gillmore, 14 May, 14 Jun, and

9 Aug 1861, T1255, roll 16, 32:238, 309–10, 407; Ltrs, J. D. Kurtz to Q. A. Gillmore, 12 Aug and 24 Sep

1861, T1255, roll 16, 32:408, 520; U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing

Office, 1881), hereinafter OR, ser. 1, vol. 5, 618–19; Malles,

Bridge Building in Wartime, 290–91; Duane Abbot, and Merrill, Organization of theBridge

Equipage, 13.

6.Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The

Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992), 11; George C. Rable, Conflict of

Command: George McClellan, Abraham Lincoln, and the Politics of War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 2023), 120; Earl J. Hess, Civil War Logistics: A Study of Military

Transportation(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 184–85; Gilbert Thompson,

The Engineer Battalion in the Civil War: A Contribution to the History of the United States

Engineers, rev. John W. N. Schulz, Occasional Papers of the Engineer School 44 (Washington, DC:

Press of the Engineer School, 1910), 6–7, 23–24; Mark A. Smith, ed., A Volunteer in the Regulars: The

Civil War Journal and Memoir of Gilbert Thompson, US Engineer Battalion (Knoxville: University of

Tennessee Press, 2020), 23; Duane, Abbot, and Merrill, Organization of the Bridge Equipage , 12–13.

7. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil

War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 424; J. G. Barnard and W. F. Barry, Report

of the Engineer and Artillery Operations of the Army of the Potomac, From Its Organization to the Close

of the Peninsular Campaign (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1863), 14–15; James C. Duane, Manual for

Engineer Troops (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862), 17; Calvin D. Cowles, Atlas to Accompany the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing

Office, 1891–1895), Plate CVI; Duane, Abbot, and Merrill, Organization of the Bridge Equipage, 13.

8. J.G. Barnard and W. F. Barry, Report of Engineer and

Artillery Operations of the Army of the Potomac From Its Organization to the Close of the

Peninsular Campaign (New York: Van Nostrand, 1863), 13–14; Mark A. Smith, “A Crucial Leavening of

Expertise: Engineer Soldiers and the Transmission of Military Proficiency in the American Civil War,”

Civil War History 66, no. 1 (Mar 2020): 23–25, 29; OR, ser. 1, vol. 19, pt. 1, 169, ser.

1, vol. 21, 49, ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 156, ser. 1, vol. 27, pt. 1, 155, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 1, 216, ser.

1, vol. 29, pt. 1, 667.

9. SO 83, Army of the Potomac, 17 Mar 1862, 15th New York

Engs, Regimental Order Book, 50, Book Records of Volunteer Union Organizations, Entry 112–115, RG 94,

Records of the Adjutant General’s Office 1780–1917, NAB (hereinafter 15NYE); Ltr, G. B. McClellan to A.

Lincoln, 6 Apr 1862, in The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence,

1861–1865 , ed. Stephen W. Sears (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1989), 231;

Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 57–58.

10. J.C. Duane, “Return of the Battalion of US Engineer

Troops,” Mar 1862, Returns from Regular ArmyEngineer Battalions Sept. 1846–June 1916, National Archives

Microfilm Publication M690, 10 rolls, RG 94, NAB, roll 1 (cited hereinafter as M690, all citations to roll

1); Thompson,Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 8, 10.

11. Capt. J. C. Duane, “Return of Battalion of US

Engineer Troops,” Apr 1862, M690; Ltr, J. G.Barnard to R. B. Marcy, 26 Jan 1863, in Barnard and Barry,

Report of Engineer and Artillery Operations, 14–15; Ltr, J. G. Barnard to J. G. Totten, 6 May 1862,

in Barnard and Barry, Report of Engineer and Artillery Operations, 141–42; Jnl of the Siege of

Yorktown, 5 Apr to 5 May, 1862, in Barnard and Barry, Report of Engineer and Artillery Operations,

151–52, 162, 164, 170, 172, 176–77, 186; Ltr, B. S. Alexander to J. G. Barnard, 28 Jan 1863, in Barnard and

Barry, Report of Engineer and Artillery Operations, 71–79, 82; Rpt of Maj. Gen. McClellan, 4 Aug

1863, OR , ser. 1, vol. 11, pt. 1, 22.

12. Phillip M. Thienel, Mr. Lincoln’s Bridge

Builders: The Right Hand of American Genius (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 2000), 59; Bruce

Catton, Reflections on the Civil War, ed. John Leekley (New York: Doubleday, 1981), 202–3; Thomas

Turtle, “History of the Engineer Battalion, A Paper Read before the ‘Essayons Club’ of the Corps of

Engineers, Dec. 21, 1868,” in Historical Papers Relating to the Corps of Engineers and to Engineer

Troops in the United States Army, Occasional Papers of the Engineer School 16 (Washington, DC:

Press of the Engineer School, 1904), 62; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 16–17, 105;

Ltr, Barnard to March, 26 Jan 1863, in Barnard and Barry, Report of Engineer and Artillery

Operations, 36–37; Thomas F. Army Jr., Engineering Victory: How Technology Won the Civil War

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 128; Jnl entries, 24 and 29 May 1862, in Gilbert

Thompson Jnl, MS Div, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (hereinafter Thompson Jnl); Malles, Bridge

Building in Wartime , 74, 78; Ltrs, D. P. Woodbury to J. G. Barnard, 29 May 1862 and 7 Jun 1862, in

Barnard and Barry, Report of Engineer and Artillery Operations, 93–94, 216; William J. Miller, “I

Only Wait for the River: McClellan and His Engineers on the Chickahominy,” in The Richmond Campaign of

1862: The Peninsula and the Seven Days , ed. Gary W. Gallagher (Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 2000), 54.

13. J.G. Totten to J. C. Duane, 24 Jul 1862, T1255, roll

17, 34:50; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 78, 82; Thompson, Engineer Battalion the Civil

War, 20–21; J. C. Duane, “Return of Battalion of US Engineer Troops,” Aug 1862, M690; Thompson Jnl,

11, 13, and 18 Aug 1862; Ltr, Barnard to Marcy, 26 Jan 1863, in Barnard and Barry, Report of Engineer

and Artillery Operations, 47–48; Don Pedro Quaerendo Reminisco, Life in the Union Army: Or,

Notings and Reminiscences of a Two Years’ Volunteer (New York: H. Dexter, Hamilton, 1863), 122–23.

14. “Report of Edward J. Lansing,” 15 Feb 1863, in

Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Military Statistics, State of New York (Albany, NY: Weed,

Parsons, & Co., 1867), 124–25; Thompson Jnl, 19, 22, and 31 Aug, 1, 3, and 15 Sep, and 26 Oct 1862; SO

4, 7 Sep 1862, in OR, ser. 1, vol. 19, pt. 2, 202; Ltr, J. G. Barnard to R. B. Marcy, 2 Sep 1862,

in OR, ser. 1, vol. 12, pt. 3, 803; “Report of Maj. James H. Neal, Nineteenth Georgia Infantry, of

Operations September 4–October 19,” 19 Nov 1862, OR, ser. 1, vol. 19, pt. 1, 1003; Reminisco,

Life in the Union Army, 123–25; C. E. Cross, “Return of Battalion of US Engineer Troops,” Sep 1862,

M690; Turtle, “History of the Engineer Battalion,” 62; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil

War, 23–24; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 85–87, 89; Stephen W. Sears, George B.

McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), 336, 338, 340.

15. George C. Rable, Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg! (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 87; Sears, George B.

McClellan, 332–38; “Report of the Committee on the Conduct of the War,” New York Times ,

24 Dec 1862; William Marvel, Burnside (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 166,

352.

16. Rable, Fredericksburg!, 43–44, 87; Marvel,

Burnside, 166; Army, Engineering Victory, 157.

17. Marvel, Burnside,165–68; “Report of the

Committee on the Conduct of the War,” New York Times, 24 Dec 1862; OR, ser. 1, vol. 21,

790–91; Rable, Fredericksburg!, 88–89, 91.

18. Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 98–101,

367n7; Marvel, Burnside, 169–70; McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 571; Rable,

Fredericksburg!, 155.

19. OR, ser. 1, vol. 21, 168–70; Kenneth W. Noe,

The Howling Storm: Weather, Climate, and the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 2020), 210; Thienel, Mr. Lincoln’s Bridge Builders, 79–81; Rable,

Fredericksburg!, 156–57, 160; Army, Engineering Victory, 158; Thompson, Engineer

Battalion in the Civil War, 25–26.

20. Rable, Fredericksburg!, 158; OR,

ser. 1, vol. 21, 170, 175–76; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 111–14, 282–84.

21. OR, ser. 1, vol. 21, 168, 170, 174, 176; M.

J. McDonough and P. S. Bond, “Use and Development of the Ponton Equipage in the United States Army with

Special Reference to the Civil War,” Professional Memoirs, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, and

Engineer Department at Large 6, no. 30 (Nov–Dec 1914), 692–758: 710; Malles, Bridge Building in

Wartime, 116–18, 284–85, 370n6–7; Earl J. Hess, Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil

War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 157–58; Noe, Howling Storm,

210–11; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 26–27.

22. Jeffrey D. Wert, The Sword of Lincoln: The Army

of the Potomac (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 212; C. E. Cross, “Return of the Battalion

of US Engineer Troops,” Jan 1863, M690; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 28–29; Henry

H. Humphreys, Andrew Atkinson Humphreys: A Biography (Philadelphia: John Winston, 1924), 182;

Reminisco, Life in the Union Army, 133–35; Smith, A Volunteer in the Regulars, 119–20;

Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 129; Marvel, Burnside, 215.

23. Smith, A Volunteer in the Regulars, 145,

149–50, 387n4 (quote from 149, emphasis inoriginal); SO 1, Engineer Brigade, Regimental Order Book, 15NYE,

191; Army, Engineering Victory, 159; May 1863 Corps of Engineer monthly return, Returns of the

Corps of Engineers, 1832–1916, National Archives Microfilm Publication M851, 22 rolls, RG 94, NAB (cited

hereinafter as M851), roll 2; William L. Lamers, Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S.

Rosecrans, USA. (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1961), 45–47. Accusations about Benham’s drinking

stemmed from his first combat performance with Rosecrans in western Virginia. In his postwar history of

Ohioans in the conflict, Whitelaw Reid wrote of Benham that he “had the misfortune of always seeing causes

for staying out of reach of the enemy when he was sober, and of being too drunk to understand his

surroundings whenever he was likely to have to fight.” The number of wartime and postwar references to his

drinking suggest a real problem. See also Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals,

and Soldiers, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, & Baldwin, 1868), 1:318; Ltr, J. G. Totten

to H. W. Benham, 19 Feb 1862, Letters and Reports of Col. Joseph G. Totten, Chief of Engineers 1803–1864, 10

vols., E146, RG 77, NAB (cited hereinafter as “Totten Letters”), 10:68–69; Malles, Bridge Building in

Wartime, 134–35, 141, 373–74n3; Ltr, Stephen M. Weld Jr. to His Father, Stephen M Weld, Sr., 29 Apr

1863, in Stephen M. Weld, War Diary and Letters of Stephen Minot Weld, 1861–1865 (Cambridge, MA:

Riverside Press, 1912), 188–89.

24. McDonough and Bond, “Use and Development of the

Ponton,” 710–11; Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996), 151–52.

25. McDonough and Bond, “Use and Development of the

Ponton,” 710–11; Ltr, Weld to His Father, 29 Apr 1863, in Weld, War Diary and Letters of Stephen Minot

Weld, 188–89; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 141, 373–74n4; Smith, A Volunteer in

the Regulars, 150, 157–59 (quote from 159, emphasis in original); Thompson, Engineer Battalion

in the Civil War, 32; Gilbert A. Youngberg, History of Engineer Troops in the United States

Army, 1775–1901, Occasional Papers of the Engineer School 37 (Washington, DC: Press of the Engineer

School, 1910), 72–73.

26. Hess, Field Armies and Fortifications,

189–92; McDonough and Bond, “Use and Development of the Ponton,” 710–11; Noe, Howling Storm, 274;

Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 144–45.

27. Walter H. Hebert, Fighting Joe Hooker

(Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1944; repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 233; Wert,

Sword of Lincoln, 260, 266; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 150–55, 376n5–6, 376–77n7,

377n12; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 34–35, 100; Smith, A Volunteer in the

Regulars, 172, 395n6. The engineers intended a second bridge for the 5 June 1863 crossing of the

Rappahannock, but they lacked sufficient boats.

28. Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil

War, 36–40, 100–101; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 156–59, 162, 164;

Army,Engineering Victory, 209; Smith, A Volunteer in the Regulars, 180, 182, 184.

29.McDonough and Bond, “Use and Development of the

Ponton,” 716; Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, 41–42; Malles, Bridge Building in

Wartime, 165–68.

30. Thompson, Engineer Battalion in the Civil

War, 42–50; Malles, Bridge Building in Wartime, 177, 179–81; Duane, Abbot, and Merrill,

Organization of the Bridge Equipage of the US Army, 14; Wert, Sword of Lincoln , 311–13,

316–22; Freeman Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980; repr.,

1991), 196–200.

31. Ltr, I. C. Woodruff to W. P. Trowbridge, 12 Sep 1863,

Miscellaneous Letters Sent by the Chief of Engineers 1812–1869, 25 vols., National Archives Microfilm

Publication M1113, 8 rolls, RG 77 (hereinafter M1113), roll 8, 22:410, NAB; Cir, J. D. Kurtz, 8 Dec 1863,

T1255, roll 18, 36:197; Ltrs, J. D. Kurtz to W. P. Trowbridge, 8 Dec 1863 and 8 Jan 1864, M1113, roll 8,

22:476, 495; Ltr, I. C. Woodruff to W. P. Trowbridge, 5 Mar 1864, M1113, roll 8, 22:563; Ltr, J. G. Totten

to J. C. Duane, 4 Feb 1864, T1255, roll 18, 36:329–30; Cowles, Atlas to Accompany the Official

Records, Plate CVI; McDonough and Bond, “Use and Development of the Ponton,” 731; Cir, R.

Delafield, 20 Dec 1864, T1255, roll 19, 37:474; OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 1, 649–50. It is likely

that the Engineer Department reviewed and approved all these plans through the Pontoon Board, which existed

from January 1863 through September 1864. It initially included Lt. Chauncey B. Reese, Capt. Barton S.

Alexander, and Maj. George W. Cullum, but Reese returned to the field in March 1863, and thereafter only

Alexander and Cullum comprised the board. See also “Return of the Officers of the Corps of Engineers,”