How does the Army Retain Warrant Officers?

One CW5’s vantage point

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Brandon Wilson, U.S. Army Signal School

Article published on: April 1, 2024 in the Army Communicator Spring 2024 Edition

Read Time: < 5 mins

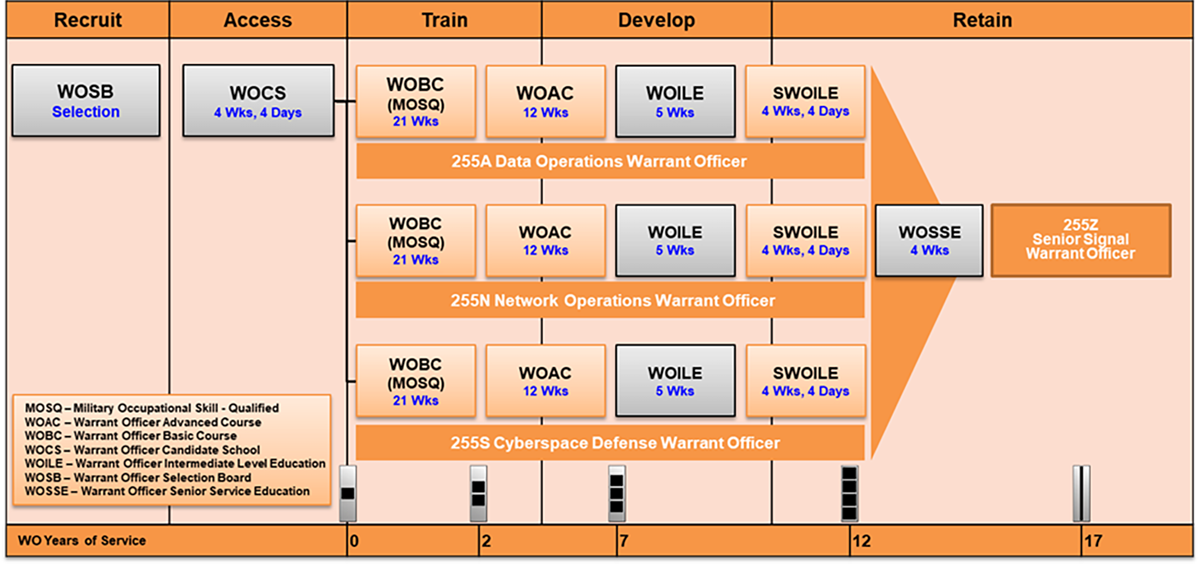

Figure 1 - Signal Warrant Officer Development Model

In the past few years, warrant officer retention has become a key issue for the Army as it struggles to retain warrant officers in grades W3 and W4 across all branches. In fact, signal warrant officers (255A and 255S) are among the top 5 critical shortage military occupational specialties (out of 48 warrant officer MOSs) for U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM). It is widely understood that these shortages significantly degrade Army readiness as warrant officer expertise is critical in enabling units to accomplish their mission.

So, how did the Army get here? The answer is both simple and nuanced. In short, warrant officers retired en masse – faster than the Army could develop their successors. Furthermore, our acquisition methods created a scenario that enabled Soldiers to retire before achieving senior warrant officer grades (W3-W5). Unsurprisingly, more than 90% of warrant officer losses are driven by retirement. In addition, approximately 58% of warrant officers in grade W3 retire at 21 years of active federal service (AFS). I suppose the remaining 40% either retire later than 21 years or remain in service and progress to grades W4 and W5. Nevertheless, neither of these facts is alarming as one should expect Soldiers to retire around 20 years AFS.

So, why is warrant officer retirement an issue for the Army? Does the Army expect warrant officers to serve beyond 20 years AFS? If so, what are some of the incentives to remain in service beyond 20 years, and how do those incentives compare to those gained post-retirement? This article does not address retention beyond 20 years AFS, except in the case of the officer retention bonus.

From my vantage point, the issue isn’t that warrant officers retire at 20 years AFS. The problem is that warrant officers retire at 20 years AFS before obtaining the grade of W4, and in many cases, W3. For example, when warrant officers retire at W2, the Army can’t develop them into W3s, W4s, or W5s, and subsequently employ their expertise. Moreover, if too many warrant officers retire in grades W3 and W4 before the Army has a chance to promote their successors, then manpower shortages emerge since the Army cannot develop a W3 overnight. It takes 7 years to develop technical warrant officers into grade W3 (eight years for aviators) and 12 years to develop W4s (14 years for aviators). Consequently, retirements in the scenario above can significantly impact manpower and degrade Army readiness.

In a perfect model, retirements shouldn’t significantly degrade manpower since the Army has a natural attrition model based upon its authorized strength. As warrant officer grades increase, authorizations in those grades decrease; authorizations known as “personnel structure” are documented personnel capabilities units require and are authorized at echelon. For example, the Army requires fewer W5s than W4s, and fewer W4s than W3s, and so on. As a result, when warrant officers in senior grades retire, the Army simply promotes their successors based on the number of authorizations in that grade. However, when the number of retirements is disproportionate to the Army’s capacity to develop (i.e. promote) successors, issues arise.

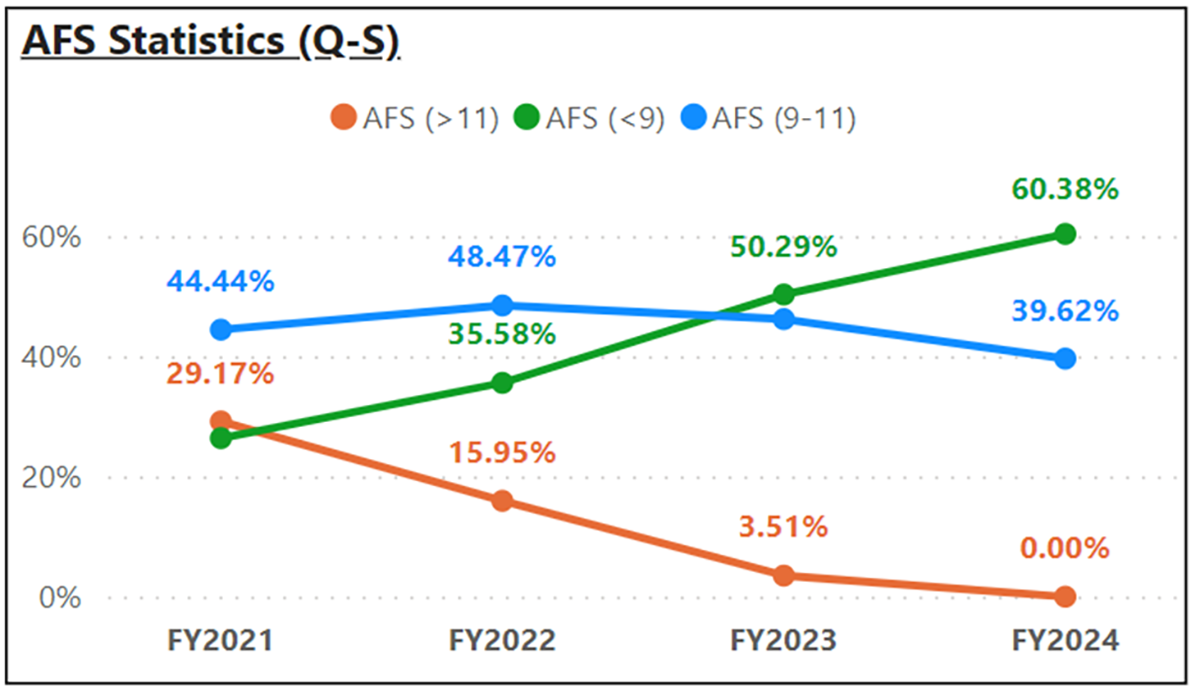

Figure 2 - Active Federal Service Statistics for Signal Warrant Officers

The Army understands these manpower requirements, which is why it codifies a goal to acquire warrant officers with 8 years AFS or less. If the Army can acquire warrant officers in this manner, then it can sustainably develop these warrant officers from W1 to W4 prior to retirement, thereby providing units the capabilities they require. Otherwise, the Army assumes risk in permitting Soldiers with more than 8 years AFS to become warrant officers.

Today, a Soldier can apply to become a warrant officer without a waiver if they have less than 12 years AFS. At 12 years AFS and beyond, Soldiers must request an AFS waiver, which is formally adjudicated by Headquarters, Department of the Army, Deputy Chief of Staff (HQDA DCS) G1. In the past, HQDA DCS G1 approved these AFS waiver requests in large percentages, which increased the risk of warrant officers retiring before obtaining senior warrant officer grades. In recent years, the Army realized those risks as warrant officers retired en masse across several branches. In other words, the retention problems we face today were created nearly a decade ago (between 7-12 years).

Recognizing its own warrant officer retention woes, Signal Proponent launched a strategic campaign in Fiscal Year 2022 to significantly reduce AFS waiver approvals and simultaneously increase the acquisition of warrant officers with 8 years or less AFS in accordance with Army goals. Signal has steadily increased this trend by double-digits each year – a success story. However, the Army will not reap the benefits of this strategy until calendar year 2029, when warrant officers selected in calendar year 2022 reach the grade of W3, and in year 2034, when this same cohort competes for promotion to W4. In the interim, the Army has offered an officer retention bonus to retain warrant officers currently serving in senior grades.

Officer Retention Bonus

The officer retention bonus (ORB) is essentially designed to incentivize warrant officers in critically short MOSs in the grade of W3 with 20 years AFS to remain in service beyond 20 years AFS. I suppose this is to give the Army time to develop successors to meet our authorizations. The Fiscal Year 2024 ORB offers $100,000 for 4 additional years AFS, $60,000 for 3 additional years AFS, and $30,000 for 2 additional years AFS. At the publishing of this article, 7% of signal warrant officers have asked and received the ORB.

In conclusion, the Army can sustainably develop and retain warrant officers in grades W1 – W4 if they acquire warrant officers with 8 years AFS or less.