The Trouble with LOGSTATs

By MAJ Sarah A. Barron

Article published on: October 1, 2024 in the Armor Fall 2024 Edition

Read Time: < 15 mins

“The logistics status report is the primary product used throughout the brigade and at higher levels of

command to provide a logistics snapshot of current stock status, on-hand quantities, and future requirements.

The logistics status report is a compilation of data that requires analysis before action. Providing the

commander a bunch of numbers with percentages and colors is useless. The commander requires an analysis based on

the data along with a recommendation for action.” Field Manual (FM) 4-0, Sustainment Operations , July 31,

2019.

The logistics statistics (LOGSTAT) report is a critical status report in sustainment operations. It is essential

for forecasting and coordinating resupply and ensuring combat readiness by accurately reporting logistics and

Army Health System support status. Army leaders must shift their mindset to optimize on-hand stockages and

improve reporting accuracy to avoid emergency resupply needs. Challenges arise from inconsistent reporting

frequencies hindering sustainment planning. Improving brigade LOGSTAT reporting is crucial for efficient

operations, focusing on disciplined, accurate, and timely submissions to prevent unnecessary resupply missions

and backhauling of supplies.

A comprehensive LOGSTAT is not just detailed, it is easily transmitted through multiple channels, universally

understood, and regularly practiced. While an overly detailed LOGSTAT listing every Department of Defense

Identification Code (DODIC) is excessive, a simplistic list of prowords or color codes hampers accurate resupply

forecasting. LOGSTATs should not just be simple for platoon sergeants to gather data, they should be detailed

enough for sustainment planners to refine estimates and reallocate assets as needed. A clear LOGSTAT reporting

plan, including primary, alternate, contingency and emergency (PACE) methods, should not just be implemented in

mission orders, it should be integrated into day-to-day operations, including routine garrison duties. Company,

battalion, and brigade executive officers (XOs) are not just responsible for enforcing the process, they are

crucial in ensuring timely, precise reports. Recipients and responsibilities for receiving, processing, and

disseminating brigade LOGSTATs must be clearly defined to enable success.

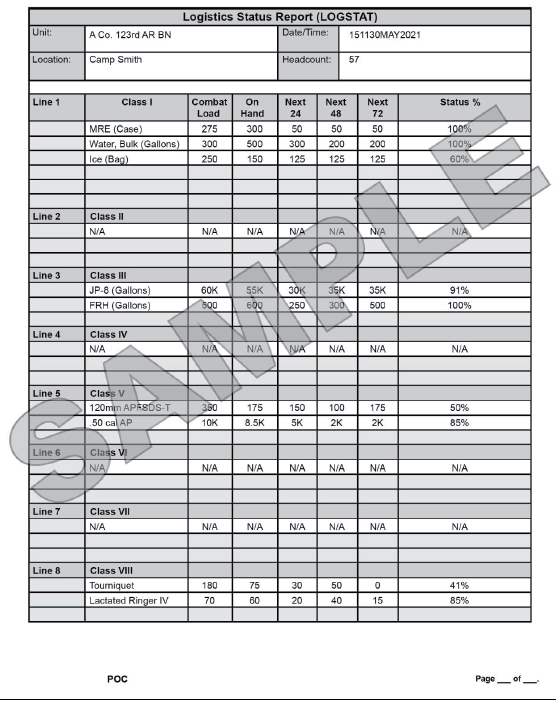

Figure 1: Example LOGSTAT Format from ATP 3-90.5 Combined Arms Battalion JUL 2021, Figure

6-3a, Pg 6-11. (U.S. Army graphic)

A constant after-action review comment from the combat training centers is that rotational training units

struggle to submit accurate and timely LOGSTATs or to accurately forecast required commodities. This results in

emergency resupplies at every level from line companies to the division logistics package (LOGPAC), potentially

desynchronizing the entire division sustainment infrastructure. The struggle to accomplish what, if taken at

face value, is a simple task is attributed to a combination of poor time management at lower echelons (the

platoon who ran out of time to count what they had on-hand and simply reported “No change” from the

previous report) and poor connectivity between lower and higher echelons (“We were jumping”;

“NIPR [Non-Secure Internet Protocol Router] was down.”; and “I sent it on JBC-P [Joint Battle

Command-Platform]. Didn’t you get it?” are all commonly heard phrases). Leaders will issue direct

guidance to subordinates to do better and the timeliness of LOGSTATs will improve, but the reports remain

largely inaccurate or insufficient to inform future sustainment planning. Our observations have found that the

problem is not so much how the units are reporting, as much as that subordinate units do not have a clear

understanding of what to report. This is further complicated by staffs at echelon who are simply consolidating

subordinate unit reports and pushing them higher without doing any analysis or using the LOGSTATs to inform

forecasts.

FM 4-0 states that LOGSTATs account for a unit’s requirements based on their task organization and assigned

mission and should include the current on-hand stockages as well as projected needs out to 72 hours.1 Army Techniques Publication (ATP)

4-90, Brigade Support Battalion, further states that accurate LOGSTATs are tailored to the commander’s

critical information requirements to support decision making. It also says that the report should include both

on-hand stockage levels as well as projections out to 72 hours.2 Maneuver doctrine states that LOGSTATs should identify on-hand amounts and

requirements to inform the commander’s decision-making process.3, 4 While all of the reviewed doctrine stated that

it was a unit responsibility to determine the exact format and reporting mechanism for LOGSTATs, if they showed

an example format, they all used the same one (Figure 1). It is unrealistic for the same format to adequately

meet the available reporting mechanisms and the level of detail required at all echelons.

To drive acuate reporting, the brigade must first standardize how the organization will count on-hand vs

consumed, what constitutes a combat or basic load, and what green-amber-red-black actually mean as a percentage

of on-hand stocks. A recommended tactic, technique and procedure (TTP) is to track commodities as on-hand until

they are issued to the end user, at which point they are considered consumed; however, that TTP may not always

apply for all commodities. If a battalion receives 350 cases of Meals Ready to Eat (MRE) (three days of supply,

assuming an M-M-A ration cycle) and immediately issues the MREs to the individual Soldier, that Class I cannot

be counted as consumed simply because it was issued to the end user. Likewise, a combined arms battalion that

has just been refueled has more than 24,000 gallons of fuel in the vehicles. That fuel must be tracked at the

company level and included in LOGSTAT reporting to fully inform commanders of their remaining operational reach.

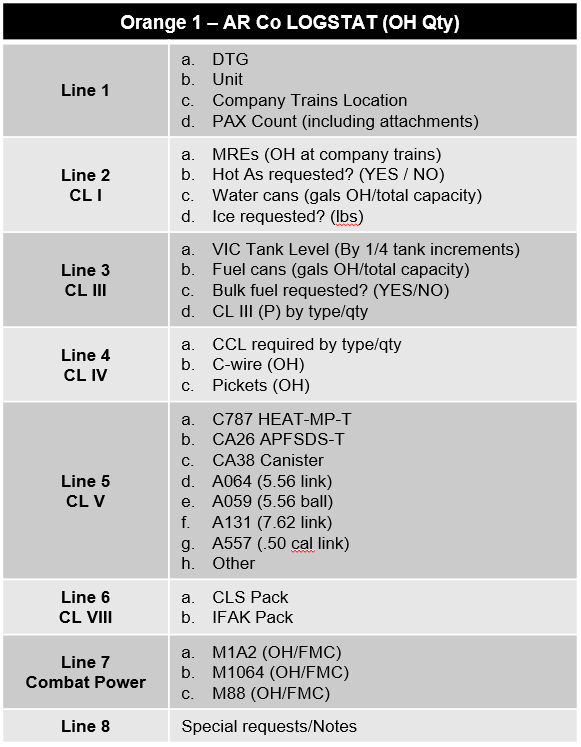

Defining Green, Amber, Red, and Black

Defining Green, Amber, Red, and Black Thresholds

| Color |

Low Threshold |

High Threshold |

| Green |

80% |

100% |

| Amber |

50% |

79% |

| Red |

30% |

49% |

| Black |

0% |

29% |

Figure 2 . Defining Green, Amber, Red, and Black in percentages. (U.S. Army Chart built by MAJ

Sarah Barron)

Defining 100 percent

Organizations must also clearly define what 100 percent means. Some commodities are easy: 100 percent of Class I

rations is three meals per Soldier per day while 100 percent of Class IIIB is the total capacity of all

available assets. Commodities such as Class IV and Class V can be slightly more difficult as each battalion has

different requirements. The brigade staff must clearly articulate what the basic load is by DODIC, item, or

combat configured load for each battalion. Once this allocation has occurred, it must be widely published to

ensure that leaders at all levels understand what their “100 percent” looks like and how far they

can operate before requiring a resupply.

This includes informing higher echelons of support of the defined value of 100 percent and what the total

operational reach is expected to be based off those numbers. After the brigade has established how they are

going to count each commodity, and at what point each commodity is considered consumed, and how 100 percent of a

commodity is defined by unit, they must now set what percentage corresponds to green-amber-red-black for use in

abbreviated reporting and what sustainment actions each report triggers.

Historically, units will begin reporting amber as soon as they fall below 90 percent and will be in the red at 70

percent. If the sustainment action tied to red on Class IIIB is to push an emergency resupply, the unit will be

expending significant, unplanned energy to distribute less than a single fuel system worth of Class IIIB.

Emergency resupplies are typically triggered by poor LOGSTAT procedures and can degrade the sustainment

architecture of the brigade by placing unnecessary LOGPACs on the road.5 This can further affect future operations as the

drivers and convoy commanders are not able to achieve a proper work-rest cycle as well as desynchronizing

planned resupply operations at both the battalion and brigade level. These inefficiencies can be mitigated by

readjusting how the organization assesses green-amber-red-black.

Throughout the Global War on Terror and ensuing contingency operations, Army leaders grew comfortable having

large amounts of commodities at hand and resupplied on all commodities easily. Units rarely operated at less

than 50 percent of commodities on-hand. It will require a mindset shift among both maneuver and sustainment

leaders to get comfortable using more of their on-hand stockages without calling for an emergency resupply,

knowing that the planned resupply will be able to return them to as close to full capacity as possible in

accordance with the priority of support. Figure 2 shows a recommended green-amber-red-black dispersion.

Adjusted dispersion

This adjusted dispersion encourages subordinate units to consume more of their on-hand commodities before

requesting resupply, which allows sustainment units to economize their movements. They can execute less

frequent, larger LOGPACs which provides additional stability to the sustainment infrastructure by increasing

predictability and improving work-rest cycle of sustainment executors. This provides the maneuver commander with

a healthier enterprise and increased operational reach.

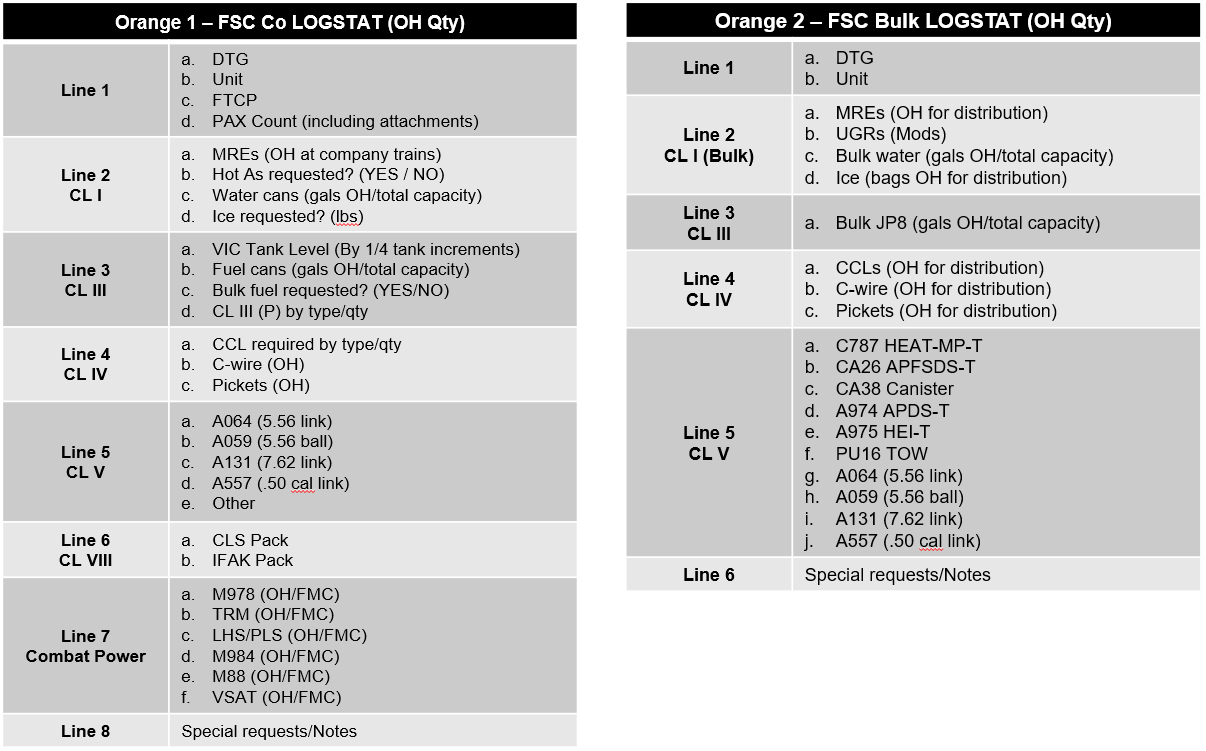

Once units have determined what data to report on the LOGSTAT, they must establish how each echelon will report

that information. It is a delicate balance of ensuring lower echelons report enough information to properly

inform decision-making while ensuring those echelons have the equipment and network necessary to submit the

report. Regular brigade and division rotations at the National Training Center make it clear that LOGSTATs

should look different at each echelon. A company that is conducting operations is unlikely to have access to a

computer and network to submit a 60+ line Excel report. While vehicle mounted Joint Battle Command –

Platforms (JBC-P) offer an Excel-like option, it is extremely difficult to manipulate a sheet of that size using

the providing stylus and keyboard. It also becomes more difficult to transmit the sheet rather than a simple

free text message. Company-level LOGSTATs should be formatted to enable easy transmission on JBC-P free text, FM

radio, or hard copy as a contingency. Additionally, the company-level LOGSTAT should focus primarily on

accurate, on-hand commodities. Figure 3 shows an example LOGSTAT for an armor company that can be easily sent by

either JBC-P free text or FM.

Figure 3. Example Armor Company LOGSTAT format. (Developed by MAJ Sarah Barron)

Company commanders are responsible for submitting accurate and timely reports, to include LOGSTATs. They may

choose to have their XO, or first sergeant gather and turn in the reports on their behalf, but that does not

absolve them of their responsibility if the LOGSTATs are late or contain poor data. If the LOGSTAT format chosen

by the battalion is too burdensome to be completed during operations, companies must provide feedback to adjust

the format until it works for both echelons. Once the format is established, company commanders must prioritize

accurate submissions or communication with higher if there is a delay.

As the battalion staff and forward support company (FSC) receive the LOGSTAT, they can now analyze the

submissions, consolidate the data and compare with their forecasts, and prepare the battalion LOGSTAT. The

staff, primarily the S-4 and the S-1, is responsible for reviewing each submission for accuracy, not simply

consolidating bad data and passing in on. If a company reports an inexplicable gain of more fuel on-hand than

they have capacity or states that they have gone from 100 percent Class IIIB to 15 percent since the last report

but hasn’t conducted any operation that would justify the change, the S-4 must reach out to the company to

find out the ground truth. Units must adjust their culture and eliminate the idea that a report submitted on

time, even if it has bad data, is acceptable or preferable to a slightly delayed, but accurate, report. Timely,

inaccurate reporting can have catastrophic effects on the unit. If each combined arms battalion reports that it

needs 5,000 gallons of fuel that it doesn’t have capacity for, the brigade will request more than 15,000

gallons of unneeded fuel from the division. This puts four M969 bulk fuel trucks with eight Soldiers on the road

unnecessarily. It also causes the FSCs to each put an extra M978 with two Soldiers on their battalion LOGPACs,

further disrupting work-rest cycles or preventing the FSCs from conducting proper maintenance on their

equipment. This wasted effort would have been prevented if the S-4 had called the XOs to validate LOGSTATs when

reports don’t align with forecasts.

Before staffs can use forecasts to validate LOGSTATs, they must first build the forecasts. Forecasting should

occur at all echelons; it is not simply on the support operations office (SPO) shop to create and maintain the

forecasts for the brigade. The Army has several forecasting tools available and in production to assist

forecasting, and sharing the forecasts with both supporting and supported units. The Operational Logistics

(OPLOG) Planner and Quick Logistics Estimation Tool (QLET) are both developed by the Combined Arms Support

Command (CASCOM) and available for download from the OPLOG Planner and Log Planning Tools Teams page.6

- QLET is an Excel sheet that is prefilled with Army Force Structure Designs and the G-4 Approved Planning

Factors that enables a user to quickly forecast based on their chosen modified table of organization and

equipment (MTOE) force file. Users can make minor changes to the anticipated consumption rate

(Minimum/Average/Maximum) for some commodities as well as tailor available distribution asset types. The

QLET data is assuming that the full MTOE of equipment is available, in use, and fully mission capable. Once

the file is loaded on the user’s computer it can be used offline. Each forecast would be saved as an

additional file.

- OPLOG Planner is a program that must be loaded on a government computer by an administrator, which can make

it more difficult to get started. It uses the same planning factors as QLET but is focused on higher

echelons of support. OPLOG planner is highly flexible and allows for building tailored task forces and

linking sustainment units to maneuver units. Planners at the brigade level and below might find OPLOG

planner challenging to get the level of detail required to maintain accurate forecasts.

- CASCOM and the Army Software Factory are also developing the Mercury: Sustainment Planning Tool.7 This tool allows the user to

create highly tailorable sustainment forecasts, down to the company level. These plans can also be shared

with other users to enable real-time, collaborative planning across echelons. As Mercury is a web-based

tool, it requires connectivity to build and share plans, which becomes more challenging at lower echelons.

The Mercury tool is still in active development and the development team invites all user to log on, make

plans, and submit feedback to continue to improve the tool.

- The fourth option for forecasting is to use the Sustainment Planning Factors found in ATP 5-0.2-1, Staff

Reference Guide Volume 1, to manually compute projected consumption based on the specific factors for the

unit.8 The ATP gives planning

factors for everything from the gallons per minute bulk fill rate for a M978 to the number of casualties

that can fit in a medium tactical vehicle. This is the recommend primary method of forecasting for battalion

and below as it does not require any connectivity and can be conducted without a computer if the

organization has identified key commodities to be forecasted ahead of time and written down the planning

factors.

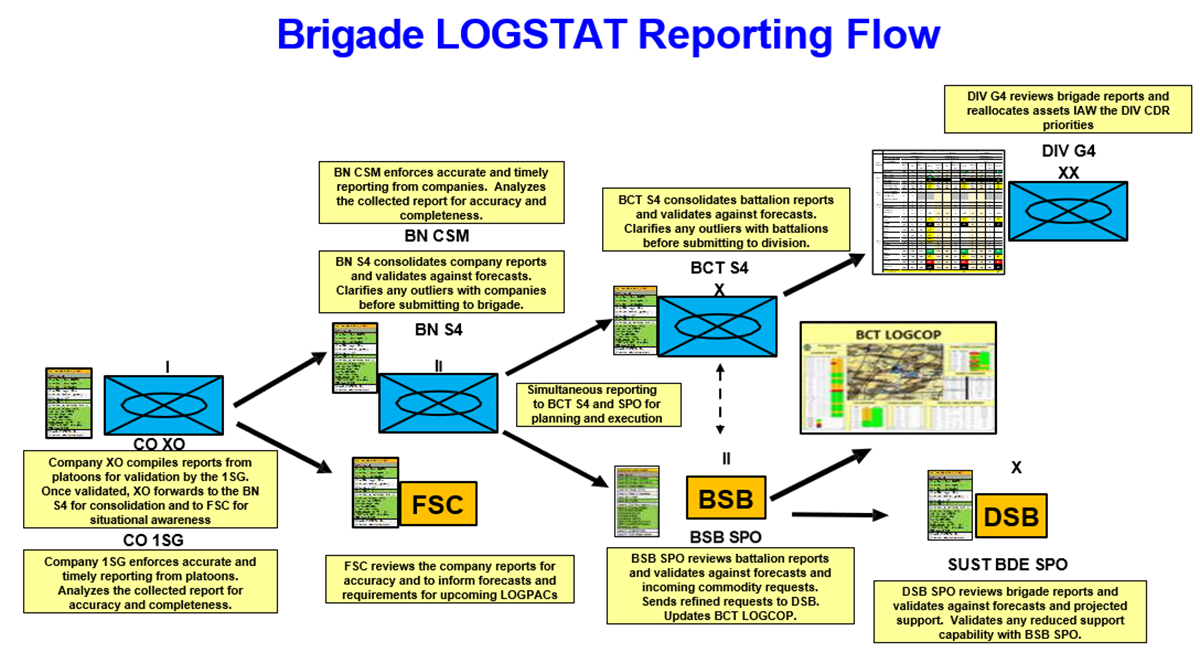

Figure 4. Example FSC LOGSTAT formats for both company internal and bulk. (Developed by MAJ

Sarah Barron)

Continuous update

Regardless of which tools the staff chooses to utilize, they must continually update their forecasts and validate

them against actual consumption. Validating the forecasts should be a continual give and take. New forecasts

validate the submitted LOGSTATs to request commodities for the next 24 hours and the actual consumption from the

previous 24 hours shows whether those forecasts were accurate. If the staff finds that their forecasts are

continually wrong, they need to relook what planning factors they are using and make modifications as needed.

Staffs must also ensure that they are forecasting against the planned operation, not just trying to get on-hand

commodities back to 100 percent. In a resource constrained environment, requesting over-forecasted requirements

to maintain 100 percent capacity will put unnecessary strain on the logistics enterprise. Conversely, if leaders

are not forecasting for the mission, they may miss a critical resourcing shortfall where the operational

requirements exceed capacity. When the shortfall is identified 24-48 hours out, there is usually time to either

cross-level internally or request additional assets for a higher echelon of support to bridge the gap. If the

shortfall is not identified until units are reporting that they are black, the unit is at risk of culminating,

even if they were at full capacity after the LOGPAC.

After the battalion staff has reviewed and validated the company LOGSTATs against their forecasts, they can

consolidate and prepare the battalion LOGSTAT for submission. At this echelon, it is likely that staff has

access to computers, even if steady connectivity is a challenge. That allows the staff to utilize tools like

Excel to assist in consolidating the FM or JBC-P company LOGSTAT submissions they received. This also enables

them to compare the company LOGSTAT requirements against the FSC bulk on-hand commodities. It is highly

recommended to have the FSC submit two LOGSTATs: the first is what they have on-hand to support their own

movement and personnel; the second shows what they are carrying as bulk to support the battalion. This prevents

miscounting commodities such as CL I MREs that are allocated to the FSC as being available for issue. Figure 4

shows an example of the recommended two FSC LOGSTATs.

Once the LOGSTATs are consolidated and analyzed, they can be submitted to brigade. Again, it is critical that

brigade is mindful of what systems the battalions consistently have available to them when dictating the format

and PACE for LOGSTAT submissions. They also need to ensure there is a codified feedback mechanism to inform the

battalions when the LOGSTAT has been received. This prevents the “I sent the LOGSTAT three hours ago,

didn’t you get it?” conversations. The reporting echelon should assume that, if they did not receive

a confirmation message, the LOGSTAT was not received, and they should move through the PACE to submit their

report until they confirm receipt. Likewise, the higher echelon must set a time following a missed report that

they begin reaching out to subordinate units to inquire about the status of the report, also utilizing the PACE

if they receive no response.

Brigade level analysis

As the brigade staff receives the battalion LOGSTATs, they also conduct staff analysis to confirm accuracy and

validate their own forecasts. The brigade S-4 and SPO must ensure that their forecasts do not conflict with each

other and, if they identify any points of friction, they address them prior to submitting the LOGSTAT to

division or confirming commodity requests to the division sustainment brigade (DSB). If the S-4 requests one

thing in the submitted LOGSTAT and the SPO requests something different to the DSB, it can create confusion in

the division sustainment enterprise and negatively affect the supplies that flow into the brigade’s area

of operations. It is vitally important that the brigade maintain and validate their own forecasts based on the

upcoming operations to ensure they are feeding accurate requests to the division 48-72 hours out. Those requests

can be refined by actual consumption in the 24- to 48-hour window, but the initial request must be submitted

with enough time for the division to react. Figure 5 shows the flow of LOGSTATs through the brigade to the

division and a brief description of responsibilities at each echelon.

Additionally, the SPO must capture the status of LOGSTAT submissions, and an assessment of critical commodities

determined by operational requirements in a logistics common operating picture (LOGCOP) that is available to the

staff and commander. The conditions described in the LOGCOP will drive commander decisions and should also drive

future planning. An incomplete or stale LOGCOP fed by poor LOGSTAT reporting will energize command involvement

to correct perceived shortcomings. This action can quickly destabilize the sustainment infrastructure and

degrade command trust in the sustainment community.

Figure 5. Brigade LOGSTAT reporting flow with brief descriptions of responsibilities at each

echelon. (Developed by MAJ Sarah Barron)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the trouble with LOGSTATs is a more multifaceted problem than simply assuming that companies and

battalions aren’t doing what they’re told. Leaders at every echelon and across warfighting functions

must contribute to setting conditions for success, from clearly defining expectations for LOGSTAT submission to

ensuring all echelons have the necessary equipment to submit according to the PACE.

As units refine and solidify their reporting processes, they must then practice them. LOGSTATs are rarely

submitted outside of field problems or CTC rotations and the LOGSTAT and forecasting processes are highly

perishable skills. They must be integrated into garrison operations and trained continuously at home station if

we hope to change the story at the CTC.

Author

MAJ Sarah A. Barron is a support operations trainer (Goldminer 05), Operations Group, Fort Irwin, CA. Her

previous assignments include support operations officer, 3 rd Combat Aviation Brigade, Hunter Army Airfield,

GA; XO, 603 rd Aviation Support Battalion, Hunter Army Airfield; combined-joint logistics officer (CJ-4),

Train Advise Assist Command – South, Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan; sustainment instructor/writer,

Maneuver Center of Excellence, Fort Moore, GA; and forward support company commander, Task Force 1 st

Battalion, 28 th Infantry Regiment, 3 rd Infantry Division, Fort Moore. MAJ Barron’s military schools

include Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS; Logistics Captains Career Course, Fort

Gregg-Adams, VA; Medical Logistics Officer Course, Fort Sam Houston, TX; and Basic Officer Leader Course,

Fort Sam Houston. She has a bachelor’s of science from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, NY; and

a master’s of business administration degree from Kansas State University.

Notes

1. FM 4-0, Sustainment Operations , July 2019, Appendix E,

Page E-1.

2. Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 4-90, Brigade Support

Battalion , June 2020, Change 1, November 2021, Chapter 2, Pg 2-20.

3. ATP 3-90.5, Combined Arms Battalion , July 2021,

Chapter 6, Page 6-10.

4. ATP 3-21.20, Infantry Battalion , December 2017,

Appendix H, Page H-15.

5. ATP 4-90, Brigade Support Battalion , June 2020, Change

1, November 2021, Chapter 6, Page 6-3.

6. TR-SCoE OPLOG Planner and Log Planning Tools TR-SCoE OPLOG Planner and Log Planning Tools | General | Microsoft Teams .

7. Mercury: Sustainment Planning Tool https://mercury.swf.army.mil/ .

8. ATP 5-0.2-1 , Staff Reference Guide , December 2020,

Appendix G.

Acronym Quick-Scan

ATP – Army Techniques Publication

CASCOM – – Combined Arms Support Command

DODIC – Department of Defense Identification Code

FM – field manual

POI – program of instruction

FSC – forward support company

JBC-P – Joint Battle Command-Platform

LOGCOP – logistics common operating picture

LOGPAC – logistics package

LOGSTAT – logistics statistics, (or) logistics status

MRE – Meals Ready to Eat

MTOE – modified table of organization and equipment

OPLOG – Operational Logistics

PACE – primary, alternate, contingency and emergency

QLET – Quick Logistics Estimation Tool

TTP – tactics, techniques and procedures

XO – executive officer