Air Defenders are Force Protectors

Rediscovering and Returning to Short Range Air Defense Historical Force protection Role

By 2LT Ian Murren

Article published on: January 1, 2023 in the 2023 Air Defense Artillery Journal, Issue 1

Read Time: < 20 mins

Figure 1: Fire Base’s ADA assets respond to an enemy night attack in Vietnam.

SHORAD’s “Do or Die”

With the proliferation of unmanned aircraft systems to state and non-state actors in the new era of warfare, Short Range Air Defense will increasingly need to counteract this emerging threat. Enemies, in the future, will use coordinated attacks with Class 1 or 2 UAS and ground units against frontline and logistical areas. To counteract this, designs for SHORAD units need to have the capability to engage and defeat both types of threats closely. Planners must consider the demands of urban environments when designing SHORAD vehicles. To do so, ADA must design SHORAD vehicles with cannons with the “three highs”: high caliber, high velocity and high rates of fire. SHORAD vehicles with the “three highs” will help accomplish the primary task of defeating enemy air assets and make the platform flexible enough to fulfill the force protection role SHORAD has historically occupied. Force protection can defend assets, equipment and personnel from multi-dimensional attacks. ADA thrived when the force protection role was embraced in SHORAD design during the Vietnam War. When the force protection role was largely ignored in SHORAD design, specifically with the lightly armored Avenger vulnerabilities to small-arms fire, ADA suffered. Leaders must embrace the inherent Joint nature of ADA as it can be a potent force against targets both on the ground and in the air on the future battlefield as it has been in the past.

Introduction

As LTG James Rainey said on Day Two of the 2021 Fire’s Conference, the ADA “branch is in a sort of identity crisis.” It is amid this “identity crisis” that has the potential to either make or break the branch not only on the battlefield but also in the budget rooms. Since the absence of a SHORAD branch has led to a break in institutional knowledge of a critical component of ADA, a reexamination of branch history will give insights as to what knowledge might have been lost. A look at the history of the branch, one can see an exciting opportunity that has gone unrealized for the past 20 years and, if recovered by the branch, will guarantee not only the security of forces and budgets but also a recovery of prestige that Air Defenders have been seeking since it has been largely forgotten in the Global War on Terror (GWOT). The ADA branch has long had a “force protection” role it has been uniquely suited for, and as LTG Rainey pointed out, Air Defenders need to “grab the role for the protection of the force” and “demand (our) seat at the maneuver table.” To properly fulfill the “Protection” Warfighting function means not only protection from air threats but also using SHORAD vehicles cannons that have high caliber, high velocity, and high rates of fire (the three highs) in the War fighting function of “Fires” to engage and destroy enemy ground threats. The added capabilities will give broader flexibility to commanders to employ ADA in two War Fighting Functions that no other branch can provide.

Historical Context

Vietnam: The War that Made the Modern ADA Branch

Imagine the Americans at Fire Base Khe Sanh in 1968: being outmanned, outmaneuvered and out of options, forced to dig in their heels and dare the enemy to take the airfield from them. Those at home had heard the stories of the hard-fighting Marines, but few had counted on the Air Defenders. Few had fought next to them, never seen a “Quad .50” turn back an enemy assault or an M42 “Duster” rip apart an entire regiment of NVA in a matter of a few minutes, but everyone who had seen them in combat knew they were magnificent.

For months, Air Defenders such as 1LT Bruce Geiger secured the firebase at Khe Sanh and the surrounding areas. 1LT Geiger’s detachment of “Dusters” armed with dual 40mm cannons positioned in dug-in positions was instrumental in adding precision firepower to the apexes of the Khe Sanh airfield. “Dusters” were not only used in base protection but in convoy protection too. Just down the road from Khe Sanh, a few weeks earlier, a supply convoy of Marines was ambushed along the route that connected Khe Sanh and other nearby firebases, like the regional command center at Camp Carroll, along the Vietnamese DMZ. A Marine quick reaction force, including two tanks, was dispatched to relieve the convoy when suddenly the QRF became victim of a second ambush. Camp Carroll was now under threat of being cut off, their QRF was in danger of being overrun, and whoever they sent out next would have to rescue two pockets of Marines. CPT Vincent Tedesco and his compliment of “Dusters” and “Quad .50s” pulled their vehicles off the line at Camp Carroll, rolled down to both sites, fought off the enemy, and got everyone from both pockets back before nightfall. What were these incredible machines of war that seemed to excel where others came short and what were they doing in Vietnam where there was no threat from the sky for the whole war?

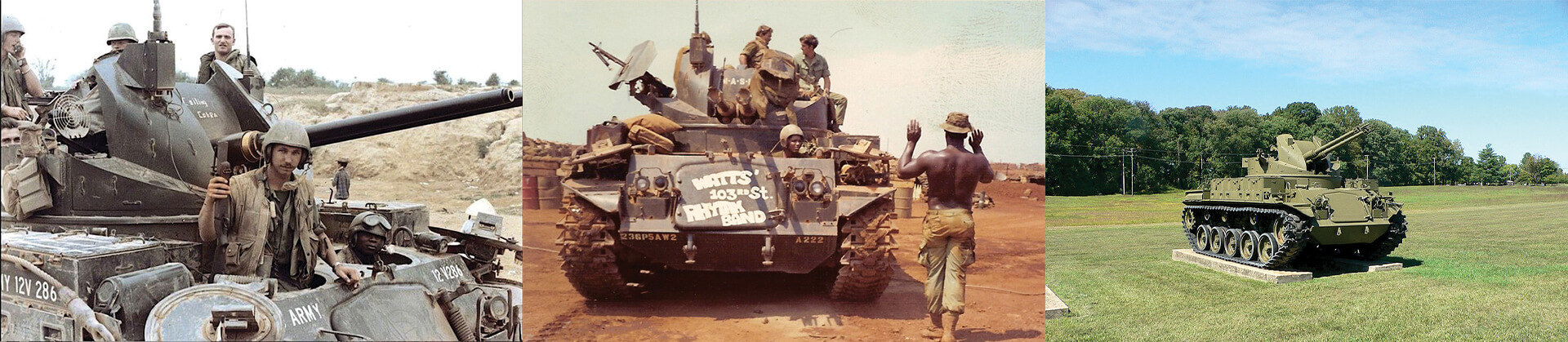

Figure 2: M42 Duster on the move in Vietnam

The M42 “Duster” was an anti-aircraft turret with duel Bofor 40 mm cannons mounted on a Bulldog tank chassis (a light tank meant to replace the Chaffee tank of WW2). Firing 240 rpm out of each gun of proximity fused rounds that detonate after impacts at ranges beyond 88 feet. The “Duster” proved itself not only as a devastating anti-air weapon but also as an excellent anti-personnel vehicle. The M19 (which had the same turret mounted as the “Duster” but on a Chaffee chassis) had served in the Korean War in a similar role but as the Chaffee was phased out, so was the M19. The “Duster” had a typical crew of seven (one driver, one commander, one radio operator, one gunner and two reloaders) and was rather cramped and exposed in most cases. The small vehicle size, open turret, and need to keep feeding the hungry guns made the crewmembers dangerously exposed to small-arms fire. Even the vehicle driver, as detailed in SGT Joseph Belardo’s book “Dusterman,” in his relative safety inside the driver’s hatch, would often have to expose themselves to enemy fire to deliver reserve ammunition to the turret crew.

As the name implies, the “Quad .50” was four M2 .50 caliber machine guns put together in a turret configuration and put on the back of a five-ton truck. While the “Duster” could trace its lineage to the Korean War, the “Quad .50” could trace it back to WWII. The Army needed to defend their motorized and mechanized formations with mobile air defense and mounted M2 machine guns onto M16 halftracks. When Soldiers realized the potential of four M2 machine guns suppressing and destroying enemy positions, it became very popular with ground forces. The configuration was so successful that it transitioned mostly unchanged, except for the half-track replaced by five-ton trucks through the Korean War and into the Vietnam War.

So, what was ADA doing in Vietnam? Officially, to combat possible low-flying North Vietnamese aerial attacks on U.S. bases in South Vietnam. Though that threat never materialized, the ADA batteries that deployed to Vietnam found great success in a force protection role assigned to guard convoys and firebases. The combination of the overwhelming fire of “Quad .50” and hard-hitting 40 mm cannons from the “Duster” quickly gained a reputation as a fearsome opponent to the insurgents. There were some limitations with ammunition capacity, crew exposure to enemy fire and the “Duster” struggled in off-road missions. The “Duster’s” 14-year-old design by the Vietnam War, though simple to maintain by crews, had difficulties finding spare parts. Nevertheless, Air Defenders were sought after as force multipliers by Army and Marine bases across Vietnam to protect valuable assets. Air Defenders allowed commanders to have a better economy of force and focus precious resources on other missions, such as search-and-destroy. Leaders could rest easy knowing their bases and convoys were well protected by their ADA units.

Operation Iraqi Freedom: The War that Misunderstood Air Defense

However, as the Cold War ended, the biggest threat to U.S. global air dominance was greatly diminished. The responsibility for air supremacy could be entirely shifted to the Air Force, U.S. planners thought. The U.S. moved toward a predominant missile-based system with the Avenger introduced in 1989. The main armament of the Avenger is two stinger missile pods with a total capacity of eight missiles and a single .50 (12.7 mm) caliber machine gun with only 200 rounds.

U.S. Army brings back it Avenger surface-to-air missile systems mounted on a High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle, commonly known as the Humvee. (Photo: Georgios Moumoulidis: UAS Vision)

When Operation Iraqi Freedom began, especially once the counterinsurgency operation started, no air defense missions were left. SHORAD units found it difficult to adapt their equipment to the new environment of COIN and nation-building. The Avenger turrets’ High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles were mounted on were too heavy to up-armor in an environment quickly becoming saturated with improvised explosive devices. There were attempts to adapt the Avenger with a “Heavy” variant that exchanged one of the two missile pods for 500 more rounds of .50 caliber ammunition to help return Avengers to the force protection role of guarding convoys and bases. However, it was found that the new variant did not prove itself well in the new mission. Faced with shifting priorities and budget cuts as the GWOT intensified, SHORAD units began to see their numbers dwindle until the decision to dissolve all SHORAD units was made.

A Quick Aside on the “Three Highs”

While the “three highs” have been mentioned, there needs to be definitions and explanations for why they are essential. The three highs refer to:

High Caliber: SHORAD assets should have high caliber, usually above 20 mm, to engage air (especially armored Helicopters) and ground threat. 20 mm is also larger than most mounted weaponry on vehicles that rely on the .50 caliber (12.7 mm) M2. The higher caliber brings extra firepower that can help suppress or destroy enemy formations, especially when they ambush scenarios. In Vietnam, ADA units protecting convoys were intended to lay down suppressive fire against the enemy while the rest of the convoy escaped the “kill zone.”

High Velocity: Engaging airborne threats, it is important to flatten the projectile’s trajectory in flight. The high velocity not only flattens trajectory but also reduces the amount of time air threats can maneuver out of the way of a projectile. High velocity also extends the guns’ effective range as they can travel farther vertically before succumbing to gravity’s pull.

High Rates of Fire: As any novice shooter knows, firing more rounds down range increases the probability of hitting a target, especially fast-moving targets. The ability to quickly gain fire supremacy on a ground target, especially when the allied force is ambushed, is key to regaining the initiative. Precious moments could mean the difference between significant or no friendly casualties in sudden attacks.

The “Three Highs” rule is not definitive but instead supposed to inform the development of SHORAD vehicles on what has historically been successful. The “Quad .50” is an exception as it has a lower caliber and lower individual rate of fire per M2 than later ADA equipment; however, it makes up for it in an impressive total volume of fire with four M2s. There is also an unmeasurable moral impact of both forces. Seeing four .50 caliber machine guns concentrate on an enemy position has an infectious ability to convince friendly soldiers that they can win a fight. Having a “Fire Dragon” evaporate comrades with thundering guns undoubtedly negatively impacts the psyche of an opponent’s disposition on continuing an engagement. The conflicts of the future will also be broadcast on social media and other platforms. The impressive firepower of cannons with “three highs” might also be able to improve morale on the Homefront when images of tomorrow’s “Fire Dragons” filter back into people’s social media feeds.

Vietnam versus Iraq: Comparison

While ADA equipment has been used in an anti-personnel role ever since it adapted machine guns to an air defense role in WW1, Vietnam and Operation Iraqi Freedom were chosen to be examined because they were both similar in the sense of being large-scale COIN wars that consumed a generation of American war planning and resources. So, why did the ADA branch fair so much better in Vietnam and not Iraq despite both being chiefly COIN conflicts? It is not the mission set, as both wars did not present any air targets for their ground-based systems to engage and saw ADA pressed into other force protection roles. The most significant difference is the equipment and how well it conformed to the principles of Air Defense. There are six: mass, mix, mobility, integration, flexibility and agility. We can use some of these principles to judge the ADA platforms from both eras. Integration and mass will not be compared as those principles have more to do with how commanders use their force rather than comparing the platforms. Survivability will also be added because, in the force protection role, ADA systems should anticipate being closely engaged by enemy ground forces.

Mix

Though in air defense, mix tends to refer to the ability to engage a mix of threats with a mix of engagement ranges, this mindset can be applied to a force protection role as well. The “Duster” and “Quad .50” brought their main armament and secondary weapons. Many “Duster” crews brought M60 machine guns to complement their heavier 40 mm cannons, whose ammunition needed 88 feet between muzzle and target before the impact fuse would activate. The mix of equipment and firepower allowed independent ADA units to have a variety of weapon systems to engage a variety of targets at various ranges.

In Iraq, however, the single .50 caliber machine gun left much to be desired as it could not depress its gun far enough in specific positions to engage ground targets. ADA units have little in the way of variety to fire at ground-based enemy personnel with their system. Still, there was no easy way to adjust the firing rate to conserve precious ammunition. The Avenger utterly fails in having the “three highs” in this regard. While having a significant rate of fire of 1200-1300 rpm, the Avenger’s single-stream 12.7 mm round firepower is not much compared to the Vietnam-era equipment. The “Quad .50”, though having a lower of 575 rpm (as it was a different variant) on each of its guns, made up for what it lacked in quantity totaling 2300 rpm with all guns blazing. The “Quad .50” could also overcome its smaller caliber, for ADA weaponry, with its volume of fire against ground and air targets.

Agility/Mobility

The HMMWV chassis is the superior system compared to the aging tank and truck chassis used by the “Duster” in Vietnam. Though vastly different environments, deserts, and jungles are about as opposite as biomes get, the Vietnam-era vehicles usually clung to the single-lane roads. At the same time, the HMMWV had more flexibility to traverse the open roads and Iraqi countryside. The Avenger turret did significantly limit the advantages of the HMMWV platform with its awkward turret placement. The Avenger turret threw off the center of balance, making the platform have difficulty getting over inclines in terrain and issues with speed as the turret substantially weighed down the system. Though mobility is not a strong suit of either ADA platform, this does not mean that systems like the “Duster” and “Quad .50” were not mobile enough for their role. Though not exceptional for their speed, the Vietnam-era equipment was only attached to QRFs if they could keep pace with other vehicles of the time. Agility and mobility are essential though understanding mobile needs to be put in context for the mission SHORAD systems are attached. If war planners of today are planning for the next large conventional land war, they should develop equipment that can keep pace with the maneuver forces. FM 3-01 specifically mentions the gap in capability in all ADA platforms to keep up with maneuver forces. The mountainous jungle terrain of Vietnam allowed time for the “Dusters” and “Quad .50” to keep pace with the mobility of mechanized forces in a way that a fast-paced war of maneuver in the Northern European plains would not have afforded either platform.

Flexibility

First, the Vietnam era with its complementing systems of the “Quad .50” and twin 40 mm “Duster.” The ability of ADA assets to adapt to various missions, including base defense, convoy protection, and fire support in urban environments, gave commanders great flexibility in utilizing ADA assets. The combination of “Dusters” and “Quad .50s” was so impressive the Marine Corps requested to “borrow” ADA units from the Army.

In the Iraq War, the experience was very different. Even after a new variant was developed, the Avenger system had great difficulty adapting to a convoy protection role. The heavy turret made it impossible to up armor the vehicle, like the other HMMWVS were, without overloading the frame. The unarmored HMMWVS were, therefore, vulnerable to not only IEDs but also small arms attacks that could penetrate the cabins of the system. The bulky turret and the inability of the vehicle to depress its guns when facing forward severely limited its ability to engage enemies. The designers had intentionally created a dead space in front of the vehicle to prevent the turret from accidentally shooting or damaging the crew or vehicle on which is was mounted. Also, the minimal ammunition capacity, though an issue for all ADA vehicles, was highly apparent, with an average of only 200 – 700 rounds on the system. The vehicle must also be dismounted to reload both the M2 machine gun and the Stinger pods. Limited engagement space and ammunition prevented this vehicle from being widely utilized in any role outside of its narrow mission set.

Survivability

Though survivability is not one of the AMD principles, it would be an oversight not to include it. The “Duster” and “Quad .50” suffered from glaring gaps in armor to protect its crew from ground fire. Though the Duster had a half-covered turret, most of the crew was exposed. Only the driver and commander seats were partially in the hull, only leaving the head exposed when their respective hatches were open. Those in the turret had their torsos perpetually exposed. In the “Quad .50,” the crew fared worse as the four reloaders in the bed of the truck were totally exposed, and only the gunner was partially exposed as he sat in the armored turret.

The Avenger suffered from many of the same issues as the “Quad .50” as there is very little armor protecting the gunner and crew. However, the “Quad .50” had a few advantages over the Avenger. The turret of an Avenger severely restricts the freedom of movement of the gunner. With a very awkward plexiglass door to the operator’s cabin, The Avenger turret would prove much harder to dismount than the open platform the “Quad .50” had, which crew members could jump off if the turret area became too dangerous. Furthermore, the driving compartment of a “Quad .50” truck had been up-armored extensively to protect the crew inside from being killed by small-arms fire. The Avenger system, due to its heavy turret and light HMMWV chasse, could not be up armored. The Avenger promptly became obsolete in the Iraqi theater, which quickly began increasing armor on everything from personnel to vehicles. The practically unarmored Avenger could not withstand even small-arms fire, let alone an increasingly sophisticated IED threat. While the Vietnam equipment could rely on some armor and its awesome firepower to suppress the enemy, the Avenger boasted neither of these advantages.

Conclusion of Historical Analysis

While capability gaps exist within both eras, the more flexible, mixed and survivable Vietnam-era equipment has the right ingredients for countering multi-dimensional threats. In this era wherein a force protection role of logistics, urban operations and firebases, the branch made a name for itself amongst its peer branches. Focusing solely on the Air Defense roles led to the creation of the Avenger, which failed to adapt, even when modified, to changing combat conditions. Further evidence of success or failure can be seen in the interservice relationship regarding the air defense mission. The Marines relied on the Army ADA components for their force protection. Through Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Marines had decided against adopting the Avenger in favor of an organic LAV-AD that embraces the Air Defense principles more closely. The LAV-AD could complete the same missions the Avenger could and in complex environments in a variety of roles. The LAV-AD also had eight stingers to complement its rotary 25 mm cannon, which could elevate higher than the regular HMMWV weapon mounts, which is advantageous for engaging targets on steep angles in urban or mountainous terrain. LAV-ADs were used in urban operations, much like how the “Dusters” were used alongside Marines in the fight for Hue City during the Tet Offensive.

The M42 40 mm Self-Propelled Anti-Aircraft Gun, or “Duster,” is an American armored light air-defense gun built for the United States Army from 1952 until December 1959, in service until 1988. (Photo credits: Left, Mark Pellegrini, U.S. Army Ordnance Museum [Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD] Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-2.5; Middle: the Army Historical Foundation; Right: Bill Maloney, Pennsylvania Military Museum)

ADA in Urban Environments

Maximizing ADA as Force protection

One of the unique capabilities ADA brings to the maneuver table is that it is one of the few branches that can operate and thrive in urban environments. While the ADA in Vietnam is mostly remembered for operating in environments surrounded by either jungle or elephant grass, ADA also proved itself in urban environments. In the battle for Hue City during the Tet offensive, M42 “Dusters” were brought in to provide fire support for Marines. The 40 mm guns could suppress and kill enemies hidden in tall buildings with their streams of fire better than their cousin, the M48 tank. Another advantage is that M42 “Dusters” had to have a high gun elevation that could be as high as 85 degrees, which proved extremely useful when shooting at the tops of buildings from close or awkward positions.

ADA should absolutely embrace operating in urban and complex environments in their force protection role. Whether in urban streets or on roads overlooked by cliffs, the unparalleled ability of ADA to put effective fire on enemies perched above friendly forces is indispensable. The mounts on a vehicle such as the HMMWV only have a 53-degree elevation is insufficient to engage enemies on higher floors, forcing their occupants to dismount to engage the enemy with small arms. With the added risk of class 1 UAS being used in urban environments, it will be more important than ever to have ADA assets capable of operating there. During the battle of Mosul, Iraqi security forces were consistently harassed by UAS that could drop munitions onto the thin armor of the tops of vehicles. With no way to counter the UAS and their presence so frequent, often Iraqi forces would become lackadaisical in seeking cover. Hostile UAS will operate in urban environments and so should SHORAD, as part of their force protection role.

Recommendations

When designing an ADA vehicle, it is essential to ensure a force protection role is also envisioned for the vehicle. Not focusing on this dual role shows a lack of understanding of the history and principles of air defense. The ADA branch needs to take advantage of its current prioritization by the Army to turn the revival of SHORAD into a Renaissance. Successfully taking back the force protection role will make other branches realize the importance of ADA assets in the field and budgeting priorities for years to come. The “Duster” was built starting in 1952, and it had to wait a decade to prove itself in the jungles of Vietnam. Commanders in Vietnam, both Army and Marine, understood how ADA units could be force multipliers on escort and base duties, maximizing the economy of force. The ADA’s performance in such roles in Vietnam won the respect of other branches opening the way for the branch to become independent in administration and funding from Field Artillery.

Failing to take advantage of this window of opportunity we have now will eventually lead down the same path that led to the death throes of ADA branch funding that led to the dissolution of SHORAD units in the early 2000s. Instead of having funding concentrated in Army ADA, it could be split, as it was in Iraq, between Army and Marine programs. The LAV-AD program was ultimately scrapped because there were only 12 examples, and the Marines decided they needed more conventional LAVs to replace losses. An ADA budget split between two branches could not prevent the dissolution of SHORAD’s place on the battlefield during the GWOT. Being sought after in a force protection role secured not only funding but also prestige, as ADA units were sought after through much of the Vietnam War. Being appreciated by fellow service members is extremely important to maintaining high levels of morale and, accordingly, combat readiness.

Conclusion

The goal of any Air Defender is to protect its assets. If an asset is destroyed by a clever ambush, TBM volley or UAS, the mission fails. If the enemy will be thinking with multi-dimensional attacks in mind, combining UAS with ground-based ambushes, should SHORAD designers not be thinking similarly? SHORAD equipment will need to be able to repel a UAS swarm attack and then the enemy’s complementing infantry assault in quick succession in the very near future. The conflict of tomorrow has no frontline, friendly skies or single-dimensional. SHORAD has thrived or died in this environment depending on how close it has kept to its Air Defense principles when developing its equipment. If it designs, delivers, and deploys equipment that embraces the force protection role, it will secure its assets and budgets. The Air Defense principles and the “three highs” of having high caliber, high velocity, and high rates of fire provide guidelines for a successful SHORAD vehicle. There is little time to close the gap before the tides of attention and budget priories shift to the next novel threat. The seeds of success must be planted and sowed now if we are to prevent a famine tomorrow.

Author

1LT Ian Murren graduated from Gettysburg College Cum Laude with a Bachelor of Philosophy and Political science, commissioning from the Dickinson College Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program. Murren graduated from Air Defense Artillery Basic Officers Leaders Course in October 2021 and arrived at his first duty assignment at Camp Humphreys Republic of Korea as part of 6th Battalion, 52nd Air Defense Artillery, a part of 35th Brigade.

Acknowledgments

I would like to take this time to personally thank COL (retired) Vincent Tedesco, LTC Hein, MAJ Joshua Urness, Dr. David Christensen, and Joe Belardo for helping me with this paper. Thanks, as always, to my parents for being there for me. Lastly, Andrew and Jess, I cannot thank you enough for those last-minute edits.