Beer and Skittles: Forrest Harding’s Warrant Officer

By Jim Steddum, CW5 (ret) and Dr. Leonard Momeny, Ed.D., CW5 (ret)

Article published on: October 1st 2024, in the October-December 2024 Edition of Strength in Knowledge: The Warrant Officer Journal

Read Time: < 7 mins

Major General Forrest Harding talking with Soldier in New Guinea, 1941. Private Kahn, Harding trusted Aide, picture under the handrail.

The Army is buzzing with talk about the Harding Project and greater professional discourse. Writing professionally—with candor no less, seems an odd thing in the Army, especially these days when most Soldiers, regardless of age, communicate in short bursts of words, memes, and emoticons. Chief of Staff of the Army Randy A. George, in large part through the efforts Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Griffiths, is signaling a paradigm shift in the Army’s approach to professional discourse and lighting fire again across all the Journals of the Army.

This sort of change in professional discourse has been a long time coming for the Army. At the initial and subsequent Harding Project meetings over the past year, older members of the group continue to extol the present crowds about the history of their favorite publications. Embellished stories surrounding the past prominence of various Army journals are fond recollections about a print copy of the Infantry Journal, Military Review, or some other publication being their only companion at a duty desk.

However, things are a little different now. Technology is, of course, vastly different, but so are those that read and write. And yet, it is the history and stories of others that continue to fascinate so many of us. Many would doubt a Warrant Officer would be located at the nexus of major writing efforts in US Army history, especially given the excitement of the current Harding Project. With so many senior officers writing today, there hardly seems room for a Warrant Officer to consistently contribute to the greater discussion. After all, it is difficult to consider Warrant Officers diligent consumers of published media at all, at least outside of their venerable technical manuals. One would be hard-pressed to make a case for a Warrant Officer potentially holding together one of the US Army’s greatest resurgences in professional writing.

If you are in camp with the previously described doubters of the Warrant Officer’s contribution to the Army’s historic publishing efforts, this article will soon settle those concerns. Warrant Officer’s do not idly boast their value to their respective commanders, but instead ground their confidence in the foundation laid by our grand predecessors. Remember, history is always too good to be true, and especially when it involves a Warrant Officer. It is high time to relook the history of the Harding Project namesake, and the Warrant Officer at his side.

In 1934, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Croft selected recent Army War College graduate, Major Forrest Harding, a 1909 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at Westpoint, to reinvigorate the Infantry Journal and influence creative writing [thinking] in the Army (Griffiths, 2024). In just two years, Lieutenant Colonel Harding doubled the circulation. Ninety years later, as Lieutenant Colonel Harding was rekindling the Infantry Journal (Kahn, 1942), the dominating powers in Europe and East Asia were also rekindling. The Army was integrating modern technology in the armor, cavalry, and infantry branches. Americans were surviving the middle of the Great Depression, and times were bleak for the country and the Army. But, through it all, the semi-official Infantry Journal served somewhat as the doctrine of the era at a mere $3 for six issues, communicating the latest in professional happenings across the Army (Anders, 1976).

In New York, Ely Kahn, a young Jewish man was attending Harvard with aspirations of becoming a writer. Coming from an affluent, artistic family, he was not as severely impacted by the depression as most. By 1937, he joined the writing staff of The New Yorker. Compared to Infantry Journal, The New Yorker was both young and highly successful. But there is one thing that forever bonded the two—Ely Kahn’s selection for the Draft in July, 1941 (Kahn, 1942).

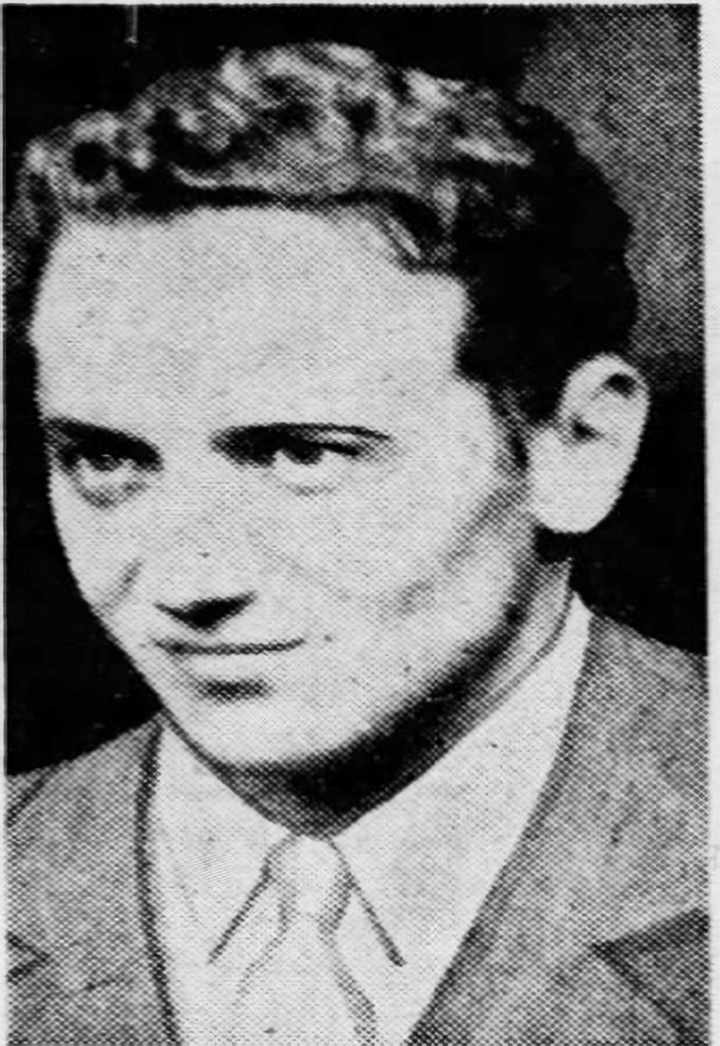

Ely Jacques Kahn, Jr. 1941

As the Nazi’s gained power in Europe and the Japanese continued their dominance in East Asia, Jack, as he was known at The New Yorker, was also gaining prominence. By 1941, Jack’s four years at the magazine saw him publish hundreds of weekly articles, and topics covered ranged from baseball to his personal interactions with kings of African states; suffice it to say he had become an expert in the field of writing and publishing. Luckily, for Kahn, his mastery of writing would not go unnoticed in the Army. What else can be said except that sometimes the Army gets talent management right.

After the brief stay at the reception center in New York, Kahn found himself on a train for what today we call Basic Combat Training at Camp Croft, South Carolina. Yes, that name should sound familiar. The camp was named after Major General Edwin Croft, the former Chief of the Infantry that selected the former Lieutenant Colonel Harding to the Infantry Journal. Private Ely Kahn was transferred to the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The division was only months old and was commanded by Major General Devers and Assistant Division Commander Brigadier General Harding, both from the USMA class of 1909. By the winter of 1942, Harding was promoted to Major General and given command of the 32d Infantry Division (Kahn, 1943a). Perhaps not ironically, Private Kahn transferred to the same Division. Indications are that Jack’s friends at The New Yorker convinced the Army to allow him to be a war correspondent as a Soldier (Weiss, 2005). Nevertheless, Jack’s connection with Harding was their mutual love of writing; Jack had earned Harding’s trust and Harding earned Jack’s loyalty.

Although Jack was assigned to Harding’s staff, he was still an Infantryman in the strongly contested battle for Buna, in Papau New Guinea in the South Pacific. After several frontal assaults, the Japanese held their positions. General Douglas MacArthur determined for victory, sent Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, another of Harding’s classmates to “[s]end Harding back, Bob. He has failed miserably,” and to “take Buna, or not come back alive” (Weiss, 2005). Unsurprisingly, Harding return to Australia with Kahn and another aide prepared to defend their positions with MacArthur who did promise to keep the relief private.

Despite hard feelings for his classmate, Major General Harding was reassigned to the Canal and Antilles Zone with now Warrant Officer (Junior Grade) Kahn in tow (Weiss, 2005). Kahn continued writing segments for The New Yorker called “The Army Life” (Kahn, 1943b). Although Harding had somewhat resigned to fate and eventually retired in 1946, Warrant Officer Kahn defended his commander, mentor, and friend through writing (Weiss, 2005). Kahn wrote a two-part biography in The New Yorker profiling the “Two-Star General” and a sequel to his first several iterations of “Army Life” published by the Infantry Journal. The sequel, called G.I. Jungle (1943b) was critical of Eichelberger and MacArthur strategy in the South Pacific and perhaps gave too much credit to Harding. Eichelberger requested that the Army investigate Warrant Officer Kahn for insubordination in uniform; however, the most he might have received was a reprimand (Weiss, 2005). Warrant Officer Kahn returned the United States after about a year in the Canal Zone. He finished the war with Army Public Affairs. In all, he published thirty-nine articles about “Army Life” in both the New Yorker and in two books. He later was war correspondent for The New Yorker in the Korean War.

So, there you have it, a Warrant Officer and writer by the side of the namesake for the Army’s newest writing program. It would seem that a Warrant Officer is always lurking around every corner of the Army, from 1918 to the present, valiantly telling the story of their teammates and working to protect commanders, through good times and bad. A final truism regarding the Warrant Officer that lurks in history can be found in a forward written for Jack’s first book. In Warrant Officer Jack Kahn’s first book, Army Life, Major General E. Forrest Harding’s foreward sums the whole story by saying, “Army life, especially in wartime, is not all beer and skittles” (Kahn, 1942, p. ix). Readers, tell the Army story and continue to protect the commanders you so faithfully serve. Their history is our history, but no one will know if you do not write about it.

Editors Note: Skittles in the 1930-40’s referred to a bar game similar to bowling, sometimes referred to as nine-pin.

Authors

Jim Steddum is a retired Chief Warrant Officer 5 and continues his service as the managing editor of Strength in Knowledge: The Warrant Officer Journal. Jim has represented the Warrant Officer in Harding Project working groups. He aims to develop professional writing in the Warrant Officer Cohort by integrating journal research and writing into the leadership and management curricula of warrant officer Professional Military Education. Jim’s accounting of the relationship of Major General Harding and Warrant Officer Kahn, as well as Kahn’s writing expertise, demonstrates the inseparable truth that warrant officers are destined to contribute to professional discourse. As the once labeled ‘Quiet Professional,’ this old warrant officer has never known that motto to be further from the truth.

Dr. Leonard Momeny is a retired Chief Warrant Officer 5 and continues to serve as an associate editor for Strength in Knowledge: The Warrant Officer Journal. Mo, as friends and Soldiers know him, represented the Warrant Officer in the Harding Project. Mo was also the second fellow for the Warrant Officer Historical Foundation and producer of the Cohort W podcast. He continues to support the Army in a civilian capacity at Fort Novosel.

References

Anders, Leslie. (1985). Gentle knight: the life and times of Major General Edwin Forrest Harding. Kent State University Press.

Griffith, Z. (2024). Renewing professional writing. Military Review. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/Professional-Military-Writing/Renewing-Professional-Writing/

Kahn, E. J. (1942). The Army life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kahn, E. J. (1943a). Profiles: Two-Star General—II. The New Yorker, 19(45), 20-21.

Kahn, E. J. (1943b). The Army life series. The New Yorker.

Kahn, E. J. (1943c). G.I. Jungle. New York: Simon and Schuster

Weiss, P. (2005, January 24). The New Yorker at war. Observer. https://observer.com/2005/01/the-new-yorker-at-war/