A Diverse Strategy for a Diverse WFF

By Colonel Barrett K. Parker (Retired)

Article published on: January 1, 2023 in the Protection 2023 Issue

Read Time: < 10 mins

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21236/AD1307225

“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

According to the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), “Army 2030 represents the largest force modernization and enterprise transformation in 40 years.” To keep pace, the U.S. Army Maneuver Support Center of Excellence (MSCoE), Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, has embarked on creating a draft Army protection warfighting function (WFF) strategy designed to improve and evolve the protection WFF.

Through the years, the Army has produced very successful strategies. The “Big Five” procurement strategy, which resulted in the delivery of the M1 Abrams battle tank, is one such success story. These strategies share a common theme; they first focus on a limited number of high-impact capabilities, deliverables, or qualities (such as a new battle tank or new field artillery with increased range) and then develop the family of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) solutions around the key deliverable.

Today’s branch, regimental, and functional strategies typically follow a similar path, first focusing on a single high-visibility, high-impact capability or deliverable and then subsequently building around the deliverable by including other supporting DOTMLPF-P solution sets. Following this formula allows for the straightforward determination of improvement in terms of measures of performance/effectiveness. For example, if we want to increase the range of a weapon, then simple mathematics will show us how much more area could be engaged in comparison to that of the previous weapon system. Through basic threat analysis, we could ascertain how to best use this capability against current and future threat systems. From this, we could devise a strategy to optimize our advantage through changes in doctrine, updates to organization design, modifications in tasks and training, and enhancements to leader development.

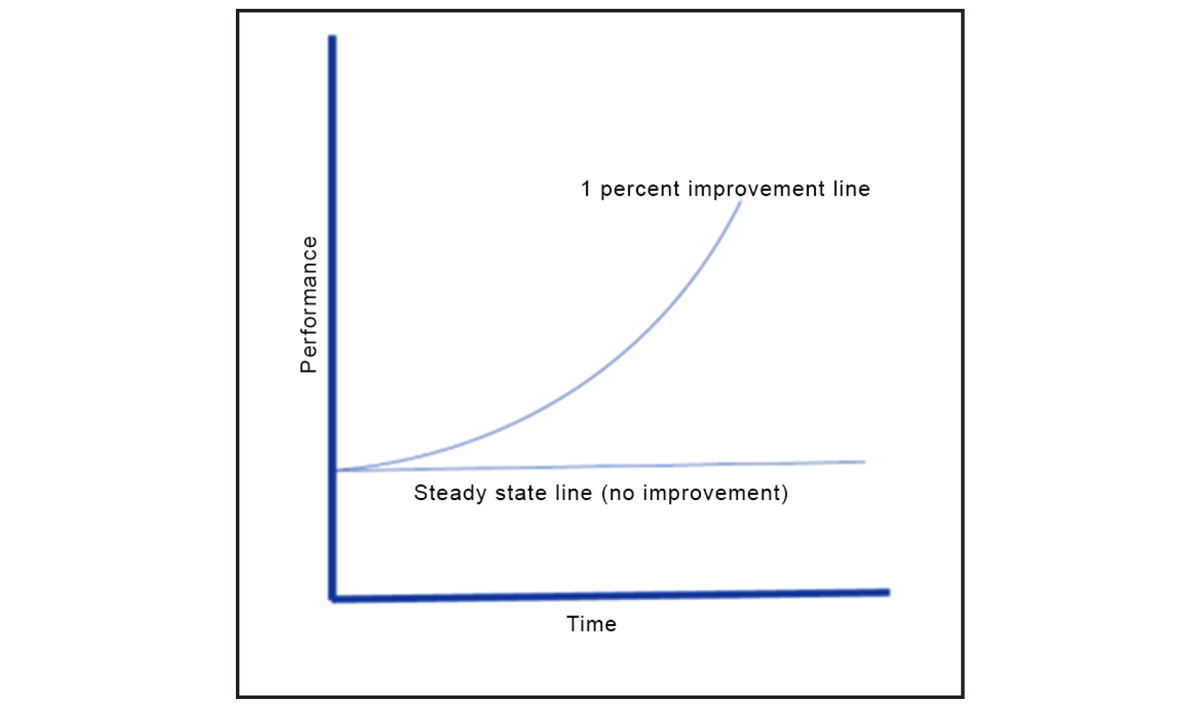

“Improving by 1 percent isn’t particularly notable— sometimes it isn’t even noticeable—but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. Here’s how the math works out: If you can get 1 percent better each day for a year, you’ll end up 37 times better by the time you’re done.”

Now, back to discussing the development of the draft Army Protection Strategy. Unlike other WFFs, the protection WFF consists of a highly diverse portfolio of capabilities. Maintained by 12 proponents, the 16 primary tasks of the protection WFF represent a marked departure from the traditional WFF construct. Obtaining and realizing any significant improvement to the protection WFF through the acquisition of a single DOTMLPF-P deliverable is impossible. Further, establishing measures of performance/effectiveness for protection WFF improvements is difficult since many protection challenges are unique to combat operations and very dificult to replicate. Several protection WFF primary tasks, such as personnel recovery, pose unique situations in which the value of new equipment or processes is often expressed subjectively.

Figure 1. A daily 1 percent improvement will result in an overall performance improvement by more than 37 times by the end of the year.

Some regiments have already championed systems that provide protection against single hazards. For example, protection against chemical agents would be addressed in the U.S. Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear School strategy. Therefore, an entirely unique approach to developing the overarching Army Protection Strategy is not just well advised, it’s imperative.

The draft Army Protection Strategy must focus on our capability to reliably deliver the ability to provide comprehensive schemes of protection. To create “windows of protection,” we must make the “preserve-deny-enable” vision of protection described in U. S. Army Futures Command (AFC) Pamphlet (Pam) 71-20-7, Army Futures Command Concept for Protection 2028, a reality. The draft Army Protection Strategy must collectively address protection at all echelons (from Soldier to theater) across all components and plan solutions with the flexibility necessary to address new, unidentified threats generated by an adaptive adversary. The only way to accomplish this is to commit to a sports strategy known as “aggregation of marginal gains.”

Mr. Dave Brailsford, performance director of a British cycling team, has described aggregation of marginal gains as the “. . . idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, then improved it by 1 percent, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together; James Clear presents this philosophy and expounds upon it by stating that “Improving by 1 percent isn’t particulary notable–sometimes it isn’t even noticeable–but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. Here’s how the math works out: If you can get 1 percent better each day for a year, you’ll end up 37 times better by the time you’re done.” Understanding this concept is essential for improving a complex portfolio such as the protection WFF, which is especially hard to evaluate with traditional metrics.

The draft Army Protection Strategy takes advantage of the aggregation of marginal gains concept by identifying dozens of individual DOTMLPF-P solutions that can be used to improve the protection WFF, addressing validated protection needs identified by AFC Pam 71-20-7 and subsequent work and then harmonizing and integrating those efforts.

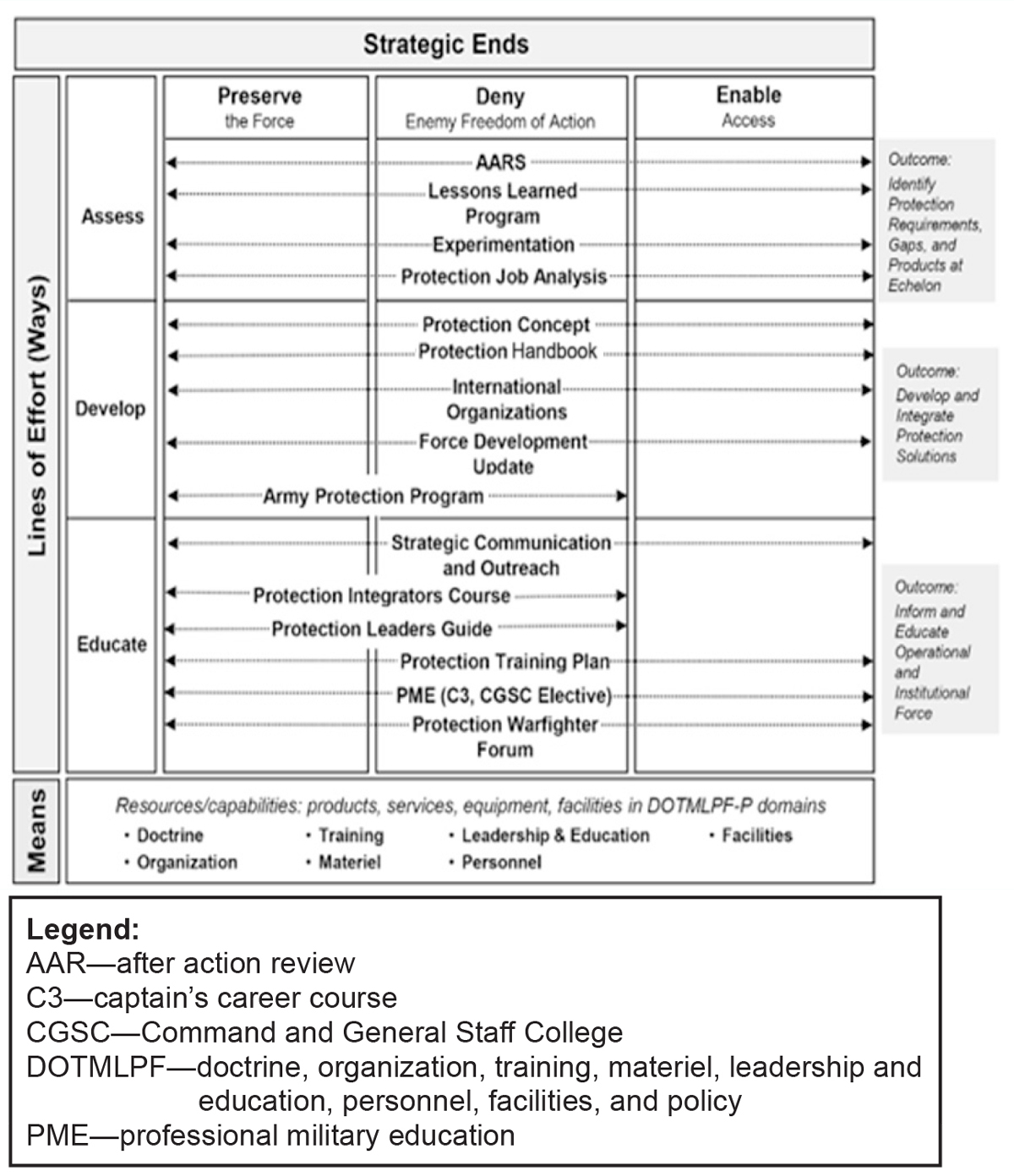

Figure 2. Army Protection Strategy ends, ways and means

For example, an examination of the leader development domain for protection reveals more than a dozen unique, ongoing efforts across the Army to improve the protection WFF. Current and projected solutions in that domain include conducting semiannual global Microsoft© Army 365 Teams-based protection WFF forums with all echelons-above-brigade protection cells; running quarterly Teams-based protection WFF working groups with all 12 TRADOC protection-owning proponents and dozens of other protection stakeholders; conducting podcasts in which changes in the protection WFF are discussed; maintaining ProtectionNet (the collaborative work forum for the protection community), located on milSuite at <https://www.milsuite.mil/community/spaces/apf/protectionnet>; conducting an annual protection conference; and creating a dynamic protection display for other conferences across the Army. Each of these leader development domain solutions interlock with solutions resident in other DOTMLPF-P domains, such as training development and protection lessons learned presented during protection WFF forums or protection engagement opportunities briefed during the Protection portion of the Army War College Theater Army Staff Course. Individually, none of these solutions “moves the needle” much; but collectively, and over time, significant improvement is realized.

The Army Protection Strategy will be organized along three main lines of effort: assess, develop, and educate. Primary processes will be associated with each of those lines. Individual DOTMLPF-P solutions (the means) will be subsequently identified and developed, leading to a significant number of unique solutions—all interlocked and supporting a defined outcome as well as the larger strategy.

As the Army and the joint force move toward large-scale combat operations, Army protection tactics, techniques, and procedures; programs; and systems must keep pace. By committing to a strategic approach of aggregation of marginal gains for the protection WFF, MSCoE will deliver the diverse and resilient program of steady protection improvement needed to support the Army division of 2030.

Endnotes

Author

Colonel Parker (Retired) is the deputy chief of the TRADOC Proponent Office–Protection, Fielded Force Integration Directorate, MSCoE. He holds a bachelor’s degree in earth science from Pennsylvania State University, University Park; a master’s degree in environmental management from Samford University, Homewood, Alabama; a master’s degree in engineering management from Missouri University of Science and Technology at Rolla; and a master’s degree in strategic studies from the U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He retired as a colonel from the U.S. Army Reserve..