Taming the Hydra

Working Toward an Integrated Protection Construct

By Mr. Stephen D. Carey Ms. Melissa E. Chadbourne Colonel Barrett K. Parker (Retired)

Article published on: January 1, 2023 in the Protection 2023 Issue

Read Time: < 15 mins

Land power ends wars. The breakneck pace with which disruptive technology is changing the operating environment—breaking down the distinctions between competition and conflict—does not change the fundamental truth that no matter how the next large-scale war among great powers starts and is fought, it will end with a decisive land campaign. When the U.S. Army can project force in time and at scale, the joint force commander is overwhelmingly capable of finishing the fight. Our adversaries know this, and they are taking measures intended to prevent the Army from globally projecting massed ground forces. If the Army can successfully defend against aggressive behaviors that threaten its programs, facilities, and personnel here at home, then we can ensure that the Army is ready and able to deploy and project force at a place and time of our choosing—not that of our adversaries. To ensure decisive force projection, the Army must reframe and reform its dis-integrated protection functions into an integrated protection construct.

In the time that it takes to read this article, advanced U.S. capabilities will confront and counter a multitude of threats such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, advanced cyber operations, or adversarial social media mis/disinformation campaigns, only to see additional threats emerge and multiply. As with the hydra of antiquity, attempts to defeat the technological drivers of today’s military modernization often expose friendly advanced capabilities and sources, increasing the opportunity for further technology-driven disruption. Our adversaries deliberately employ these disruptive technologies in support of hybrid warfare strategies that avoid direct conflict with U.S. military power, intentionally blurring the distinction between competition and conflict. This ambiguous environment enables foreign security and intelligence organizations to actively collect information about our installations, networks, systems, and critical infrastructure and to test them to prevent us from projecting forces forward in a future armed conflict. By targeting our efforts in our homeland, our adversaries have brought the fight to us and are setting conditions in their favor to interrupt our ability to mobilize, deploy, and win a large-scale war.

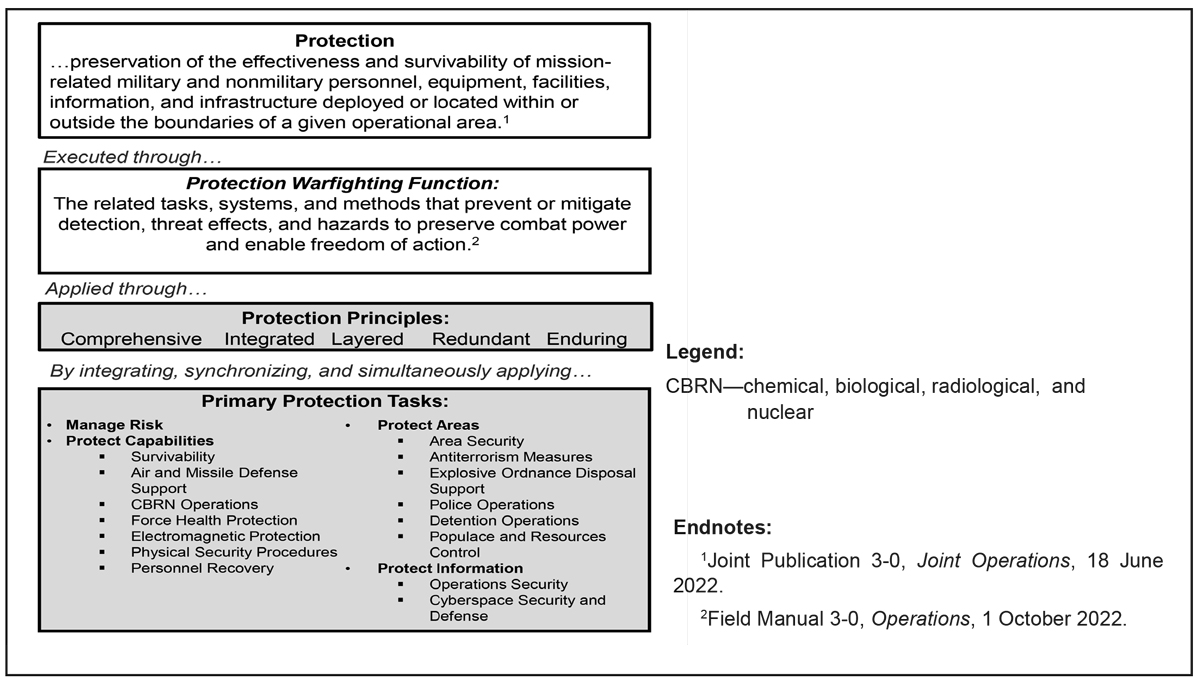

Figure 1: Protection logic map

China and Russia are currently collecting information about U.S. Army modernization by using advanced and emerging technologies, cyberspace operations, and information capabilities. Their actions have recently been demonstrated within the United States and around the world, and they continue to evolve. Although unmanned aerial vehicles or drones have been used since the Vietnam War, unmanned, commercially produced drones are now being used to deliver lethal strikes in armed conflicts. In 2017, Russian forces used a drone to target an ammunition dump in Ukraine, resulting in approximately $1 billion worth of damage, while Ukrainian forces have “used 3D printers to add tail fins to Soviet-era antitank grenades that were then dropped from an overhead commercial drone to target Russian tanks and vehicles.” New technologies continue to help advance the applications of unmanned systems that use artificial intelligence for command and control. In 2020, China tested a “swarm of loitering munitions, also often referred to as suicide drones . . . [which] underscores how the drone swarm threat, broadly, is becoming ever-more real and will present increasingly serious challenges for military forces around the world in future conflicts.”

Cyberspace operations further enable a multitude of attack vectors that may be capable of targeting communications systems or exfiltrating information. In 2019, a “denial-of-service attack on [an] encrypted messaging-service telegram disrupted communications among Hong Kong protestors.” And at the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, an attack on a satellite broadband service disrupted Internet services across Europe and affected Ukrainian military communications. Our adversaries exploit the global nature of Internet communications and social media by using networks of state media, proxy shells, and social-media influence actors who disseminate false content or amplify information that is beneficial to their efforts to influence. For example, Russian propaganda portrays Russian attacks against Ukraine as being more powerful than they actually were, thereby creating the false illusion that Ukraine is not fighting back. And Chinese influence operations have highlighted the 2023 Ohio train derailment that resulted in the release of toxic chemicals and alleged that the United States was involved in the 2022 sabotage of pipelines used to transport Russian gas. These challenges in the operating environment—both in the homeland and abroad—are only expected to intensify as we look toward 2040 and beyond.

According to General James E. Rainey, commanding general of the U.S. Army Futures Command, in future conflicts, “We are going to be fighting under constant observation and in some form of contact at all times. The enemy is going to be able to see us somewhere—electromagnetic spectrum, digitally, from space.” This new transparent battlefield will be a further challenge to Army protection efforts, requiring additional countermeasures and incorporating more data and advanced analytics to support informed decision making. Addressing these changes to the operational environment, General Rainey stated, “[This] needs to translate into every modernization effort, but more importantly into our tactics and doctrine.”

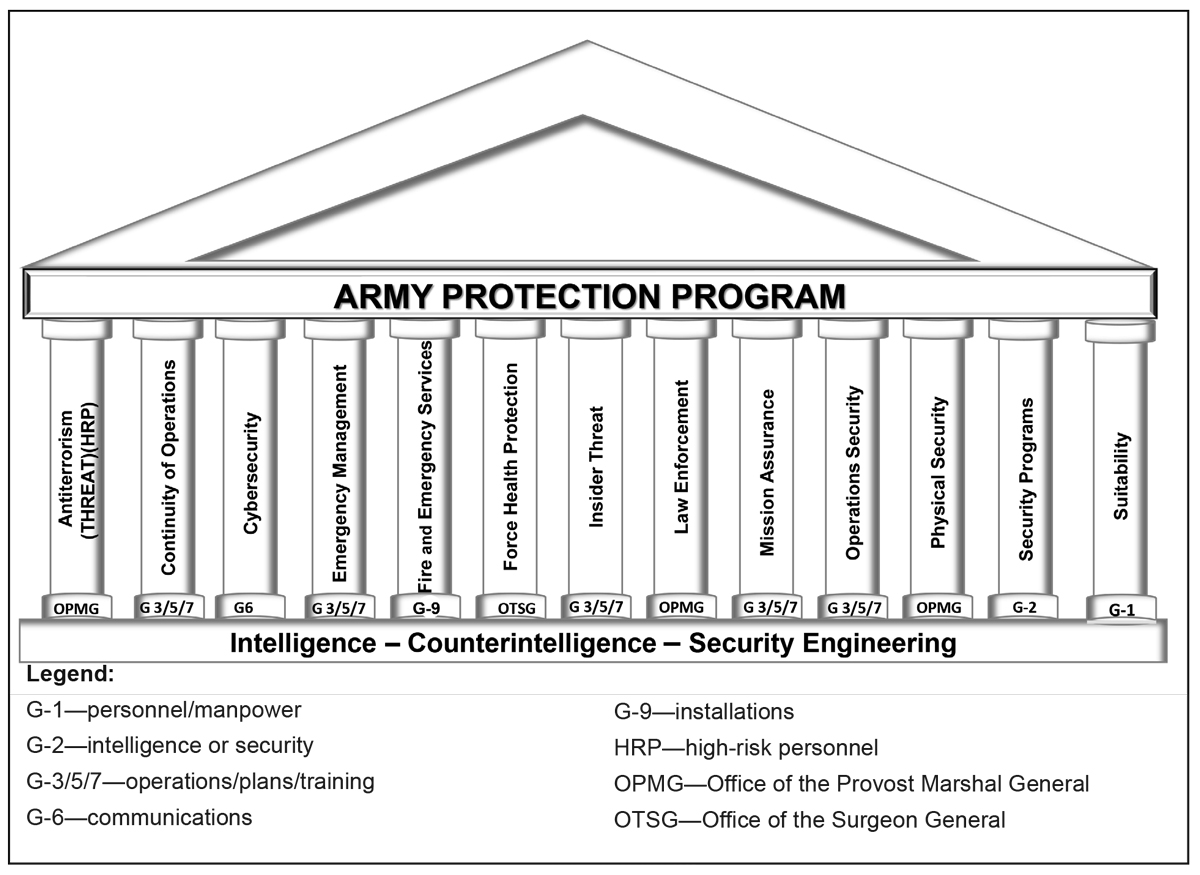

Figure 2: The Army Protection Program

For those operating in Army protection programs, activities and operations have historically been divided between warfighting and nonwarfighting functions. These divides are causing inefficiencies in how the Army conducts protection. The truth is that there are no “nonwarfighting” functions. Everything the Army does directly contributes to supporting the fight and the warfighter. We need to stop thinking about the homeland as a place where we are at rest and in relatively safety. If we truly subscribe to the concept that our installations and garrisons in the United States are under daily threat by our adversaries, then we must treat the mislabeled “nonwarfighting” protection functions as a critical part of our warfighting efforts. We must bring the war-fighting and nonwarfighting protection programs together in a way that seamlessly integrates the actions across the conflict continuum. Only by harnessing the multitude of protection functions and programs under an overarching structure can we ensure that the Army can adapt to the evolving threat landscape and rise to meet future challenges. Therefore, we propose that the Army dramatically rethink protection across the entire range of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy solutions, beginning with synchronized strategies and implementation plans that support the Army of 2030 and are aligned with the requirements for the Army of 2040.

The warfighting protection functions are currently synchronized by the U.S. Army Maneuver Support Center of Excellence (MSCoE), Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, through Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 3-37, Protection, while the nonwarfighting protection functions are coordinated through the Army Protection Program, which is managed by the Directorate of Operations, Plans, and Training (G-3/5/7), Headquarters, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., and described in Army Regulation (AR) 525-2, The Army Protection Program. As indicated in Figures 1 and 2 (page 32), there is a high degree of similarity between the protection function tasks (ADP 3-37) and the primary and enabling protection functions (AR 525-2), although they each contain unique requirements and activities. Indeed, ADP 3-37 references the Army Protection Program to ensure doctrinal consistency between the two guiding documents. While these two aspects of protection are actively undergoing adaptations and adjustments to meet the range of current threats, more work must be done to bring them closer together to prepare the Army for the threats and challenges that it will inevitably face in the future.

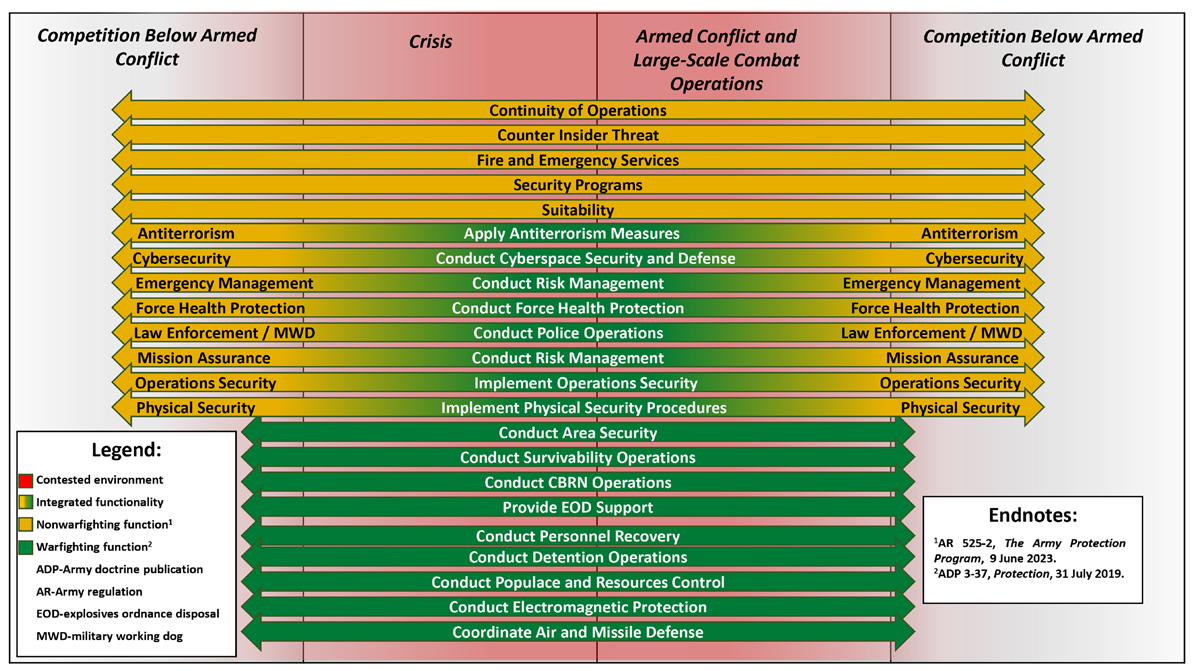

One challenging aspect of Army regulations and doctrine (including AR 525-2 and ADP 3-37) is the need for frequent updates. Discussions about whether the next iteration should add, subtract, modify, or rename protection functions (or tasks) in keeping with emerging threats and the goals of Army future concepts are never-ending. While the exact tasks to be listed are valid considerations, a bigger concern than what constitutes Army protection efforts is how the Army approaches protection. As previously mentioned, there are many similarities between warfighting and nonwarfighting protection functions and ADP 3-37 guidance references the Army Protection Program, but there is no clearly defined point at which an activity transitions from “nonwarfighting” to “warfighting.” Army protection currently operates in two friendly siloes—each operation is aware of the other, but they are not fully integrated. We instead propose a new integrated protection strategic construct—something along the lines of what is shown in Figure 3, in which the transitions between “nonwarfighting” and “warfighting” are blurred along the competition continuum. An integrated construct would align protection activities with the Army 2040 requirements to fight in a transparent and contested environment.

Figure 3. Protection Support Throughout the Army’s Strategic Context

The challenges of current and future operating environments will disrupt the Army across all domains and through all stages of force generation, modernization, readiness building, and force projection. As our adversaries exploit the competition phase with relative freedom of maneuver in the homeland, they could potentially create conditions that impede the Army from modernizing and projecting forces. We seek to prevent these activities and ensure the effective and seamless operation of Army protection functions across the blurry lines between competition and conflict. To provide ground forces that can sustain the fight across contested terrain and over time, Army protection efforts must ensure that Army forces progress from generating capability to delivering battlefield effects, unimpeded by adversary efforts that span the competition-conflict continuum. Achieving that goal requires a deliberate and concerted effort in terms not only of directing resources toward modernization and readiness activities but also of considering how we protect the personnel, programs, systems, and information that enable Army forces to prepare for deployment. Integrating the dis-integrated functions of Army protection will enable the Army to meet and overcome the challenges intended to impede Army forces from getting to the fight.

We are undertaking this challenge with deliberation and a willingness to rethink our past approaches in order to be positioned for the future. The Army Protection Division, Headquarters, Department of the Army, has begun reforming the Army Protection Program to address problems arising from current threats, vulnerabilities, and hazards. Looking to the near future, Headquarters, Department of the Army, and MSCoE must unite protection activities under an integrated protection construct that supports the full range of protection activities across the full spectrum of conflict, from fort to port to theater. This construct will drive doctrine and policy revisions that have a coordinated approach to the way forward and are linked to the future concepts being developed by the Army Futures Command. This also means that the new strategy will be implemented using the full range of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy concepts to further influence the Army enterprise. By adapting programs, policies, training, and exercises to address current threats, we can better adapt for emerging threats and better position the Army to project force to fight in a contested and transparent environment. If the Army fails at protection, we fail at projection. Only by designing a new integrated protection construct that effectively links the full range of protection activities will we fully support the Army of 2040 and beyond.

Endnotes

19.FM 3-12, Cyberspace Operations and Electromagnetic Warfare, 24 August 2021.

Authors

Mr. Carey is the deputy division chief of the Army Protection Division, G-3/5/7, Headquarters, Department of the Army. He holds a master’s degree in history from the University of Montana, Missoula, and a graduate certificate in world religions and diplomacy from George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia. He plans to complete a master’s degree in strategic studies at the U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 2024.

Ms. Chadbourne is a policy analyst supporting the Army Protection Division, G-3/5/7, Headquarters, Department of the Army. She holds a bachelor’s degree in history from Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, and a master’s degree in international relations from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Washington, D.C.

Colonel Parker (Retired) is the deputy of the TRADOC Proponent Office–Protection, Fielded Force Integration Directorate, MSCoE. He holds a bachelor’s degree in earth science from Pennsylvania State University, University Park; a master’s degree in environmental management from Samford University, Homewood, Alabama; a master’s degree in engineering management from Missouri University of Science and Technology at Rolla; and a master’s degree in strategic studies from the U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He retired as a colonel from the U.S. Army Reserve.