The Application of the U.S. Army RM Process is Broken

By Major Courtney A. Zimmerman

Article published on: January 1st 2024, In the Annual Issue of the Protection journal

Read Time: < 9 mins

Leaders address risks that could trigger decision points for the commander; however, they seldom specifically address risk to force or risk to mission. Can organizations assess unit risk to force or risk to mission using the U.S. Army risk management (RM) model during the military decision-making process (MDMP)? The answer is currently no. There may be a single point of organizational failure that prevents the implementation of RM in the operation, or there may be a lack of education about the process. Regardless, the RM process is not working effectively. This article discusses the doctrinal processes for RM and describes methods that units could use to incorporate RM into operations.

The RM Process

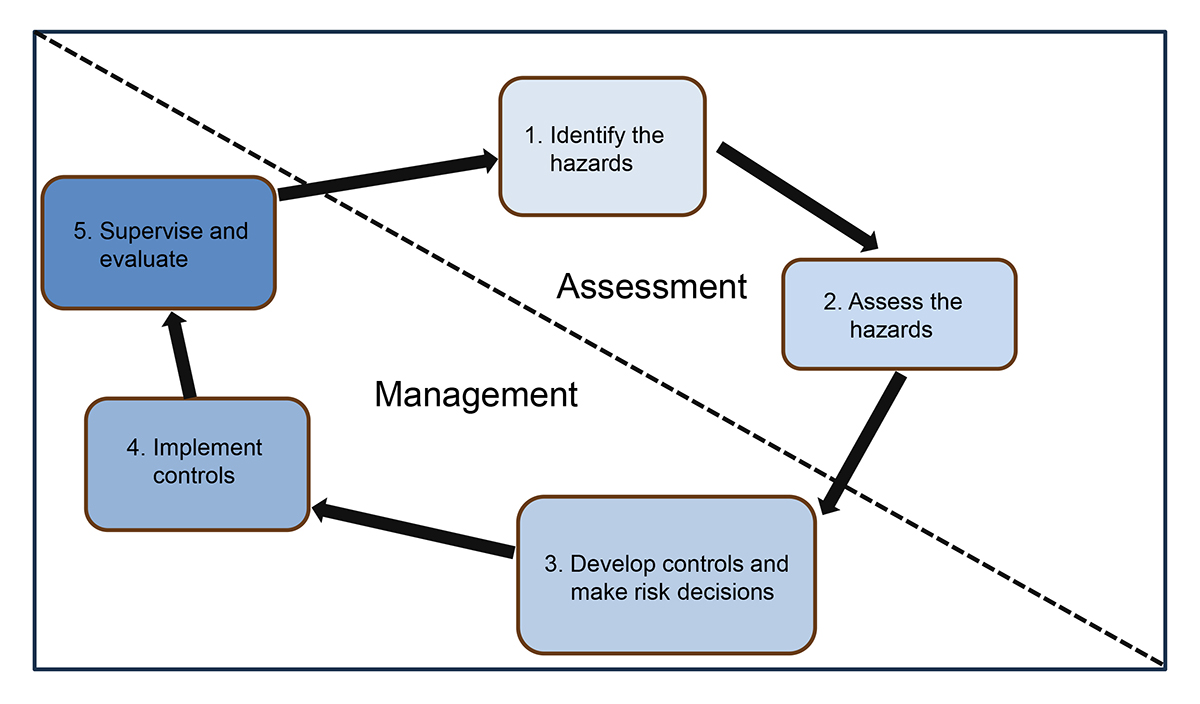

Before addressing RM at echelon, let’s define some key elements and explore how the Army conducts RM. Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 5-19, Risk Management,1 discusses conducting risk assessment and management using the framework depicted in Figure 1.

The first step of the risk assessment/management process is to identify the hazards—conditions that can potentially cause injury, illness, or death of personnel; damage to, or loss of, equipment or property; or mission degradation.2

Next the hazards must be assessed. According to ATP 5-19, risk is “the probability and severity-driven chance of loss, caused by the threat or other hazards” and analysis of the risk yields a risk level.3 Following the assessment, units consider the mitigating effects of proposed controls and iteratively reassess the risk until they determine the most effective controls. They then continuously reassess these controls to determine the residual level of risk. Commanders implement the selected controls while supervising and assessing the effectiveness of each.

Many might claim that this process applies only to garrison operations—not to combat operations. Although the requirement for a risk assessment/management process is clear, implementation becomes blurred at higher echelons. Such blurring explains why units fail to understand how to conduct the RM process. The RM capability is an invaluable tool for commanders and staff, as it provides a standardized and systematic method to identify hazards and react to changes within the operational environment.

As the operational environment evolves, RM must be conducted in order to identify risks by operational phase to help analyze risks to the mission. But RM is not a stand-alone process;4 instead, organizations must integrate RM throughout every warfighting function (WFF). Effective RM during operations depends on its full integration into the MDMP and overall operations process. The MDMP is an iterative planning methodology used to understand the situation and mission, develop a course of action, and produce an operation plan or order.5

“During mission analysis, the commander and staff focus on identifying and assessing hazards as they relate to risk to force (increased probability of the degradation of an organization’s combat power) and risk to mission (increased probability of failure to achieve a desired end state).”

—ADP 3-37, Protection, 10 January 2024.

Figure 1. Assessment Steps and Management Steps

“Risk management is the process to identify, assess, and control risks and make decisions that balance risk cost with mission benefits.”

—Joint Publication (JP) 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations, 18 June 2022.

“It is imperative that commanders and units apply the Army RM process throughout planning and execution. Commanders make risk-based decisions, and their entire organization must be comfortable continuously integrating, applying and communicating risk management to ensure appropriate decisions enabling mission success.”

—Major General Christopher G. Beck, personal e-mail correspondence

Risk Matrix

One recommendation for fixing the RM process is to apply a format to codify risk assessment in the MDMP. A methodical technique must be employed in order to recognize the hazard during each step of the MDMP. According to ADP 3-37, Protection, “The MDMP helps leaders apply thoroughness, clarity, sound judgment, logic, and professional knowledge to understand situations, develop options to solve problems, and reach decisions.”6 To be effective, commanders must hold discussions with their staffs to ensure that they understand all operational variables and to develop guidance prior to MDMP. The commander’s guidance and intent must address risk analysis /RM so that the staff understands the commander’s assessment. This understanding will drive success in this challenging but critical assessment.

Potential risks during mission analysis must be considered in the running estimates for all WFFs. However, the simple identification of risks in the operational environment is not the only requirement. Leaders must also explain how each risk affects forces or the mission. From that point forward, that specific WFF is responsible for each step of the RM process.

The development of a course of action builds upon the risks identified during mission analysis. During this phase of planning, the staff develops a more detailed plan. Therefore, the staff must assign each identified risk to a specific operation phase and estimate the probability of occurrence (high, medium, low). Just because an identified risk has a low probability of occurrence does not mean that the risk should go unidentified. The staff also begins to formulate ways to reduce each risk. Will intelligence help avoid the risk? Will fires or movement and maneuver eliminate it? Will protection help mitigate it? Or will some combination of these be required? Alternatively, the staff could determine that the best approach is to accept the risk. ADP 3-37 defines each of these terms in the following manner:

- Avoid —forego the activity that would produce unacceptable risk.

- Eliminate —take action to remove the risk or transfer it to a unit that is better-postured to manage the threat.

- Mitigate —implement measures that decrease the probability or consequence of harm.

- Accept —make an informed decision to act without further mitigating the risk.7

During the course-of-action analysis, the staff should further refine the details of each risk. In this phase of planning, the staff must show how proposed controls will affect risk and where significant risk will be incurred. While developing controls, the staff assigns required supporting tasks to units or assets. Residual risk associated with risk to force and risk to mission will accompany the identified risk.

Figure 2 contains an example of a risk matrix at the division level.

Risk to Force and Risk to Mission

To complete the commander’s risk assessment, the staff should describe risks as risk to force or risk to mission. The staff should link each hazard to the risk matrix shown in Figure 3. Identifying a hazard as red, amber, or green on Figure 3 is subjective using qualitative analysis in the risk matrix. The risk or hazard requires a refined evaluation from the staff subject matter expert. The commander must understand the controls measured upon the overall affected risk assessment, which does not negate avoided, reduced, or eliminated risks. Risks may occur in any operational phase. The overall assessments of risk to force and risk to mission should be qualitatively categorized as low, medium, high, or extremely high.8 The commander must be able to recognize vulnerabilities, identify and understand the risks, and plan to respond appropriately to protect the force and mission.

Risks Tied to a Decision Point for the Commander

The RM assessment should impact the commander’s decision point. Regardless of the model used by the staff, the staff must inform the commander of risks in time, space, and purpose and assist him/her in making decisions. Commanders may then choose to avoid, eliminate, mitigate, or accept risk. If possible, risk should first be avoided or eliminated. Then, the remaining risk should be mitigated to the extent possible before the commander chooses to accept the risk.

The commander’s critical information requirements include information that the commander deems necessary to make an informed decision. There are two subsets of critical information requirements—friendly forces information requirements and priority intelligence requirements. Friendly force information requirements include information that units need to know about themselves, and priority intelligence requirements include information that units need to know about the adversary or operational environment. Essential elements of friendly information—or information that the commander wants to hide from the enemy—are also important. RM should drive friendly force information requirements and associated decision points so that the commander is better informed, mission accomplishment is enhanced, and the force is preserved. Through reverse intelligence preparation of the battlefield and during the MDMP, the staff determines the likely enemy actions, locations, and strength. From there, the staff develops a collection plan, assigning collection in named areas of interest linked to priority intelligence requirements. Units will be assigned to collect specific assets that are further tied to decision points in the RM model. If staffs did not articulate risks based on decision points, friendly force information requirements, priority intelligence requirements, and essential elements of friendly information, then key aspects of risk to force or risk to mission that commanders should consider may not be highlighted.

| WIF |

Operational Phase |

Hazard |

Impact |

Probability |

Avoid |

Eliminate |

Mitigate |

Supporting Task |

Asset Assigned |

Risk to Mission |

Risk to Force |

| Sustainment (G4) |

|

Bypassing enemy poses a risk to sustainment units traveling along predictable routes |

Tempo, operational reach |

M |

|

|

X |

Convoy and route security |

MP |

L |

M |

| M2 (AVN) |

|

FARP vulnerability |

Operational reach is reduced |

L |

X |

X |

|

Dedicated protection force |

MP |

M |

L |

| Fires |

⭐ |

DIVARTY cannot range to FSCL |

Cannot engage HPTL |

M |

X |

|

X |

Coordinate with HPTL priority and PAA established to shape operations |

ABCT fires BN |

H |

H |

| Fires |

⭐ |

Enemy IDF mass on 3/4 and 1-3 ABCT defensive positions |

Culmination |

M |

X |

X |

X |

Request Joint fires to increase speed and maximize fire power |

DIVARTY |

H |

H |

| G39 |

|

Bothnian propaganda will be aggressive, including false claims against 4ID, and possible exploitation/amplification of any actual CIVCAS/atrocities/detainee abuse |

Delay in OPTEMPO |

M |

|

|

X |

Disrupt and degrade strategic to operational C4I systems |

PSYOPS |

M |

L |

| Protection (MP) |

|

Fratricide |

Degradation of 4ID combat power |

L |

|

|

X |

Establish contact points, IR, and LNOs |

MP |

M |

L |

L - Negligible effects on OPTEMPO

M - May require DIV to execute a branch plan

H - May prevent DIV from completing DO

Avoid - M2/Intelligence

Eliminate - M2/Fires/Nonlethal

Mitigate - Protection/PPL

Legend

4ID—4th Infantry Division

ABCT—armored brigade combat team

AVN—aviation

BN—battalion

C4I—command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence

CIVCAS—civilian casualties

DIV—division

DIVARTY—division artillery

DO—decisive operations

FARP—forward area refueling point

FSCL—fire support coordination line

G4—general staff level office for logistics

G39—information warfare staff section

HPTL—high-payoff target list

IDF—indirect fire

IR—infrared

LNO—liaison officer

M2—movement and maneuver

MP—military police

OPTEMPO—operational tempo

PAA—position area for artillery

PPL—priority protection list

PSYOPS—psychological operations

WFF—warfighting function

Figure 2. Example of a division level risk matrix

Ownership of RM

Throughout the operations process, commanders and staffs use RM to identify, prevent, and mitigate risks associated with the WFF and the effects of threats and hazards with the potential to cause friendly and civilian casualties, damage or destroy equipment, or otherwise impact mission effectiveness. RM is not the responsibility of just one person; everyone plays a part. Commanders must acknowledge this and empower executive officers and chiefs of staff to protect the force and enable mission success.

The executive officer or chief of staff must first assign the responsibility of managing the risk matrix to a WFF. According to ADP 3-37, the protection cell RM responsibilities include—

- Identify and assess hazards and propose controls for each course of action during planning and preparation for operations.

- Understand, visualize, and identify protection priorities.

- Develop goals, objectives, and priorities for the command force protection policy.

- Develop protection measures of performance and measures of effectiveness related to RM.

- Integrate and synchronize protection tasks and systems to increase the probability of mission success.

- Monitor the conduct of operations during execution, looking for variances from the protection plan or scheme of protection, and advise the commander when protection activities are not being conducted.

- Incorporate mitigation measures to reduce operational risk to the mission.

- Assess unit RM and force protection performance during operations and provide recommended changes for force protection guidance and controls.

- Capture lessons learned from RM.9

RM is also integrated with the planning and execution of operations. In some organizations, an Army civilian safety officer integrates RM into operations. That safety officer must provide technical expertise to the commander and staff. Finally, it is imperative that the assigned staff officer present an updated risk matrix to the executive officer or chief of staff.

| WIF |

Operational Phase |

Hazard |

Impact |

Probability |

Avoid |

Eliminate |

Mitigate |

Supporting Task |

Asset Assigned |

Risk to Mission |

Risk to Force |

| Protection(MP) |

2a |

Execute hostile gap (river) crossing |

Operational rach/Basing readuced |

M |

|

X |

X |

Intergated preplanned fires, ISR,FW/RW cover |

MP |

H |

M |

| C2 |

2a⭐ |

Desturction pf key C2 nodes (EW and cyber) |

Server Communications |

H |

X |

|

X |

OSEC strictly enforced; robust team to thwart AH/SAPA hackers; release phony plans |

G6 |

H |

L |

| Protection(MP) |

2a |

Destruction of bridges and dams |

Operational reach/Basing reduced |

M |

|

X |

X |

Secure critcal infastructure (bridges) by MP static positions |

MP |

M |

L |

L - Negligible effects on OPTEMPO

M - May require DIV to execute a branch plan

H - May prevent DIV from completing DO

Avoid - M2/Intelligence

Eliminate - M2/Fires/Nonlethal

Mitigate - Protection/PPL

STEPs:

- Each WFF identifies risk (hazard) and impact during MDMP (MA)

- During MDMP (COA DEV), Risk will be identified by operational phase with the probability.

- WFF formulate how the hazard will be reduced or avoided, eleminated or mitigrated- or any Combination of the three

- During MDMP conduct COA analysis in phases and issue suporting tasks associated with hazards, and risk to mission and/or force.

Risk Matrix:

- Constant refinement

- Helps CDR see risk in time, space, and purpose

- Provides XO the science to the art of adjudication

- Risk in terms of risk to mission and risk to force

Key Risks to brief CDR during BUB/CUB:

- ⭐= Risk with a DP linked to it

- HDPs are associated to NAIs answering PIRs

- Risk the unit cannot directly influence

- Risk that can cause culmination

- Risk with political consequences

Legend

AH/SAPA—South Atropian People’s Army

BUB—battle update brief

C2—command and control

CDR—commander

COA—course of action

CUB—commander’s update brief

DEV—developement

DIV—division

DO—decisive operations

DP—decision points

EW—electronic warfare

FW—fixed wing

G6—general staff level office for signal and communication

ISR—intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance

MA—mission analysis

M2—movement and maneuver

MP—military police

MDMP—military decision-making process

NAIS—named area of interest

OPSEC—operations security

PIR—priority intelligence requirements

PPL—priority protection list

RW—rotary wing

WFF—warfighting function

XO—executive officer

Figure 3. Assessment Steps and Management Steps

Conclusion

While WFFs own the risks or hazards, it is imperative that a leader within the organization to own RM. The identification of risks in time, space, and purpose will help the commander describe an operation and direct how to conduct it. The tools and knowledge necessary to inform the commander of risks and the actions required to mitigate them are in place. But our ability to apply RM in the U.S. Army is broken. By understanding the doctrinal RM process and incorporating RM into operations, unit leaders can fix this capability gap and change the culture within their organizations. Figure 3 can serve as a tool to assist with this process.

Endnotes

1 ATP 5-19, Risk Management, 9 November 2021.

2 JP 3-33, Joint Force Headquarters, 9 June 2022

3 ATP 5-19, Risk Management, 9 November 2021.

4 Ibid.

5 Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 5-0, The Operations Process, 31 July 2019.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

Author

Major Zimmerman is the chief of the Department of Instruction; Directorate of Training and Leader Development; U.S. Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear School; Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. He holds a bachelor’s degree in education from Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, and a master’s degree in environmental management from Webster University.