Overcoming Obstacles to Cyberspace Threat Intelligence

By Chief Warrant Officer 2 Travis M. Whitesel and Mr.Joseph Rudell

Article published on: July 2024 in the Engineer 2024 Annual issue

Read Time: < 9 mins

Discussion of the commercial products and services in this article does not imply any endorsement by the U.S.

Army, the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence, or any U.S. government agency.

This article is primarily relevant to intelligence professionals supporting cyberspace operations at the U.S.

Army Cyber Command and the U.S. Army Network Enterprise Technology Command. However, with the intelligence

profession's continuing expansion and overlap into the cyberspace domain, the article will serve as a

primer for discussion about obstacles facing those in the digital fight.

Introduction

The U.S. Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM) G-2 is developing and implementing cyberspace threat

intelligence (CTI) techniques to protect the Department of Defense Information Network-Army (DoDIN-A). However,

current challenges with the incident management and reporting processes hinder the intelligence community's

ability to provide relevant and predictive intelligence to drive operations. This article captures the lessons

learned and obstacles identified by NETCOM G-2 while implementing new tactics, techniques, and procedures. The

article also conveys recommendations assisting the signal community with enabling CTI for improved threat

visibility within the cyberspace domain.

Issues of the Cyberspace Domain

Current challenges with the cyberspace domain's incident management process include:

- Lack of investment in a unified toolset for incident management.

- Lack of standardization in the reporting process.

- Misunderstanding of the role of intelligence within the process.

These obstacles significantly hinder predictive analysis and an in-depth examination of the domain's problem

sets. Resolving these problems will enable better protection and sustainment of the DoDIN-A.

Lack of Investment in a Unified Toolset. This failure to invest in a unified toolset for

incident management significantly affects reporting procedures because the incident management instrument is

different for each network provider.Government Accountability Office reporting highlights the problem,

indicating that in spite of investing $100 billion annually into information technology and cyberspace-related

infrastructure, the federal government has yet to achieve effective results.1 This failure to produce

practical outcomes is partially a product of not learning from past mistakes. Each incident on the DoDIN is an

opportunity to understand our visibility gaps, process failures, and configuration requirements. The approximate

12,000 cyberspace attacks against the Department of Defense (DoD) and defense industrial base since 2015

compound the issue, emphasizing the adversary's intent and capability.2 (NETCOM G-2 assesses

this number to be significantly higher.) A unified incident management toolset would provide insight into the

process failures and the threat's intent and capability, which would further improve the Army's response

through subsequent analysis. The incident management toolset is the primary entry point to capture information

about cyberspace attacks. Both industry and the various service components have proposed unified toolsets;

however, to date they have not captured requirements to collect the relevant information to enable future

analysis and data sharing.

Lack of Standardization in the Reporting Process. This failure to standardize incident

management reporting requires analysts to apply more strenuous analytic rigor to identify factors for creating

relevant and timely intelligence. Additionally, employing multiple toolsets coupled with the required fields and

descriptions of incidents varies across the DoDIN-A enterprise. These problems degrade the ability to diagnose

an incident with structured analytic techniques.

The 12,000 documented cyberspace attacks since 2015 should serve as a foundation for understanding cyberspace

threat capabilities, common targets, and trends in threat avenues of approach. However, the information

available in official repositories about these attacks is principally limited to incident response actions and

status without addressing the attack's techniques, targets, and key indicators. When an attack occurs in the

physical domain, the operational report includes all available information, including the number of enemy

personnel, potential descriptions, their capabilities, when and how the attack occurred, and descriptions of any

related artifacts. To be effective in the cyberspace domain, operatives must capture the same level of detail

about cyberspace attacks. Through standardization of the incident management reporting process, CTI will improve

the defense of the DoDIN-A.

Misunderstanding of the Role of Intelligence. Integrating intelligence into incident management

processes is essential, and the Army must actively implement procedures to include it. One critical obstacle to

implementation is the inability of intelligence professionals to access and complete incident records in a

timely manner. This is attributable to a misunderstanding of the role of intelligence in the incident management

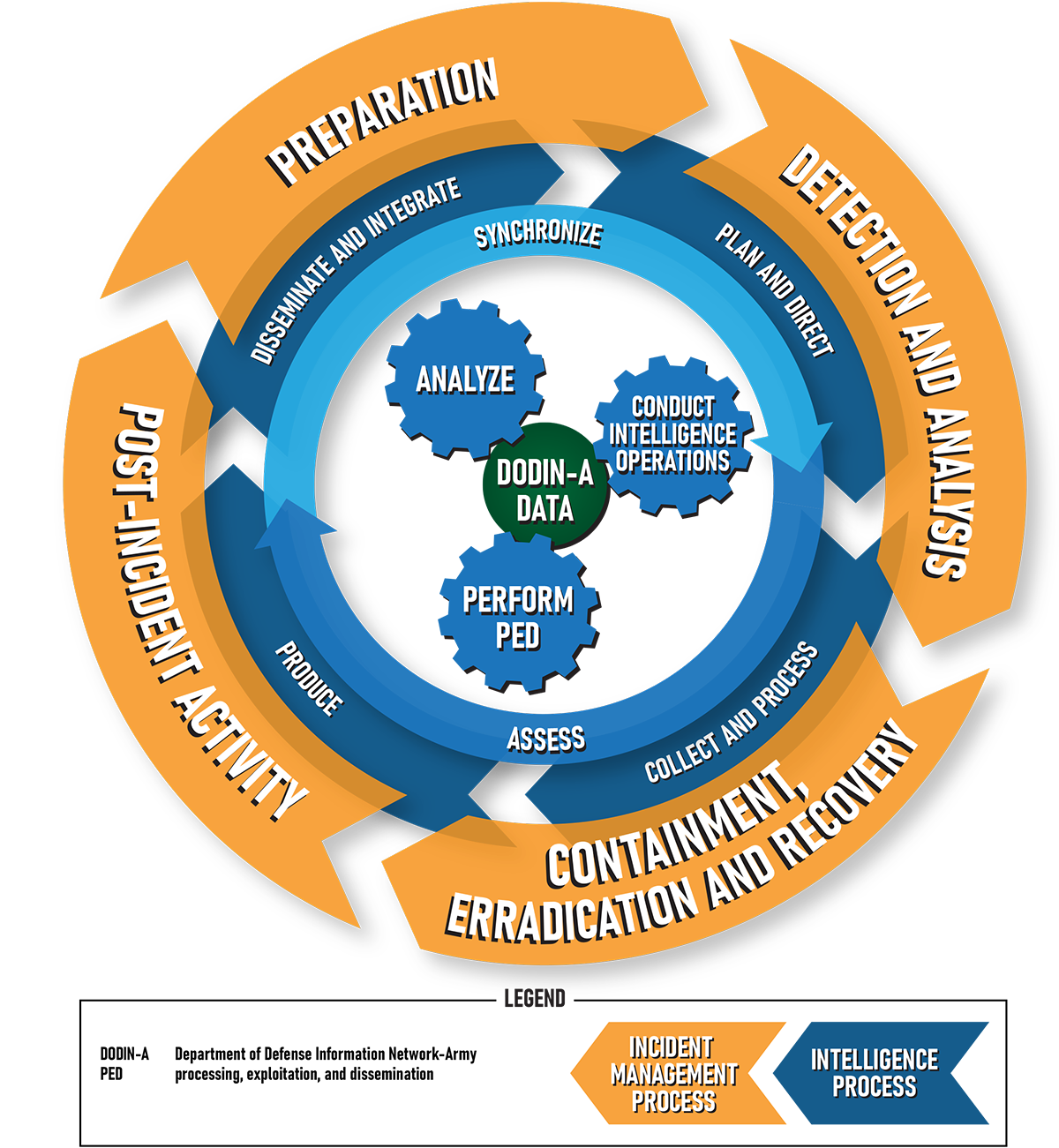

process. The incident management and intelligence processes overlap and have similar activities intended for

different purposes. (See figure on the next page.) The main difference is that, while incident management in

cyberspace operations aims to respond to and eradicate the current threat, intelligence personnel want to

exploit and analyze the information to answer intelligence requirements and reduce futurethreats.

Concerns about impacting ongoing cyberspace operations or intelligence oversight lead to hesitation in allowing

intelligence analysts to view DoDIN-A data. However, the areas of operations are friendly networks and incident

management data, which have limited risk of exposing identifying information, with regulations and processes for

handling evidence involving U.S. persons or operational requirements.

Incident response operations narrowly focus on resolving the immediate incident. Often, the process merges into

the next incident without anyone conducting a structured analysis to capture details or create an understanding

of the incident in a broader context relating to the DoDIN-A. Integrating intelligence into the incident

management process allows the information obtained during an investigation to be stored, contextualized, and

exploited without the time constraints of preparing for the next operational response. By design, the

intelligence process will capture information and identify data gaps overlooked in the initial operational

response and provide a more detailed understanding of the Army's visibility gaps in context with DoDIN-A

threats. In conjunction with the incident management process, this analysis will help prioritize defensive

measures for the DoDIN-A while making educated risk decisions.

Successes in the Commercial Environment

CTI's successes in the commercial domain provide lessons learned and operating guidelines for the Army to

consider when developing its own CTI organizations and techniques. Commercial environment CTI teams often

include individuals with a variety of skill sets who perform multiple roles simultaneously. In 2018, Microsoft

Corporation revealed that their CTI team included, among other professionals, a lawyer, a traditional

intelligence analyst, an experienced cyberspace analyst, and a technical writer. Other organizations incorporate

unique skill sets within their CTI teams tailored to their work environments. The Army has well-defined incident

management processes, but a variety of specific laws and regulations impose unique constraints. Collaboration

within the limits of those constraints, however, can expedite CTI and speed implementation of commercial

processes. Based on the NETCOM G-2's experience, when choosing the correct commercial process to adopt, one

that nests CTI into a security operations center can overcome the need for individual analysts with multiple

roles or individuals with specialized skill sets.

Another commercial CTI advantage is access to multiple data sets for analysis and enemy detection. This allows

commercial CTI analysts to corroborate data sets, which delivers significantly more context to incidents and can

shorten the time to understand the complex environment.3 Access to operational data is a key

enabler for commercial CTI operations and provides better defenses for protecting their respective networks. The

commercial sector successfully highlights the importance of incident management data for completing CTI tasks,

which the Army can leverage for success.

The commercial CTI sector has access to functional toolsets that assist in discerning complex information. Often,

one incident management service provides the data. The commercial sector's capability to standardize

incident management data and conform it to a singular toolset provides CTI professionals with familiarity and

superior functionality.4 This allows the commercial sector to

calibrate toolsets to their mission, taking advantage of professionals with longevity within the company. These

commercial successes emphasize the DoD's need to adopt a unified incident management system. They also

underscore the necessity of employing a toolset and environment that allows the analyst to access, manipulate,

and move information to support their mission.

Overlap of the Intelligence and Incident Management Processes.5

Integrating Cyber Threat Intelligence

Although many of the analytical techniques and processes used in commercial CTI originated with military

intelligence, the Army can benefit from leveraging commercial processes because of that sector's sustained

and documented successes. Several companies offer CTI techniques to deter adversaries operating on a network and

improve sensors for hardening a network. The Army can successfully integrate commercial CTI structures without

completely reworking current organizational structures. A dedicated effort by the Army to unify toolsets and

standardize processes can significantly impact the visibility and security of the cyberspace domain. One way to

accomplish this is to introduce and apply structured analytic techniques.

Intelligence professionals are already familiar with structured analysis. They use cognitive processes and

analytic tools and techniques to solve intelligence problems. Multiple cybersecurity structured analytic

techniques exist that can serve as a common language between the cyberspace and the intelligence communities.

These include the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix, the Cyber Kill Chain, and the Diamond Model. These frameworks and

techniques provide a baseline for communication and improve how intelligence professionals and cyberspace

defenders approach cyberspace incidents.

Mapping an attack through the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix framework empowers analysts to communicate how an adversary

attempts to penetrate the network. 6 provide the intelligence community

with a way to structure adversary capabilities quickly, identify how they apply to friendly networks, and

present that information to cyberspace defenders. Implementing a common language between incident management and

intelligence will result in a better understanding of attacks against the DoDIN-A and provide data in a

structure that analysts can leverage to prioritize network defense, identify future capability requirements, and

enable proactive decisions by leadership.

An integral component of Lockheed Martin's Intelligence Driven Defense model, the Cyber Kill Chain provides

intelligence analysts with a method to examine cyberspace attacks and advise cyberspace operators on adversarial

actions targeting friendly networks. It is a framework that deconstructs a cyberspace attack into seven steps to

understand the adversary's actions and objectives.7 Viewing intrusions through the lens of

the kill chain ensures cyberspace defenders capture all relevant information about an attack. A detailed kill

chain allows intelligence analysts to use the same information to conduct trend analysis on successful threat

techniques and friendly visibility gaps. Mapping an attack to gain visibility of flaws is critical for enabling

the Army to prevent future attacks.

The Center for Cyber Threat Intelligence and Threat Research created the Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis to

depict cyberspace attacks. 8 The tool relies on four different

subsets of an attack: infrastructure, victim, capability, and adversary. Viewing an intrusion through this

framework allows analysts to provide context to an attack through behavioral and technical choices. This

strategy reveals similarities between attacks and enables intelligence professionals to identify related

incidents, differentiate possible threat relationships, and identify unique traits. These capabilities are

especially important because a sizable proportion of intrusions remain unattributed. The Diamond Model, when

coupled with the Cyber Kill Chain, enables in-depth questioning of incident data, which can support operational

and strategic requirements.

Combining these three structured analytical techniques—the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix, the Cyber Kill Chain,

and the Diamond Model—provides a foundational process to gain an advantage in the cyberspace domain and

capture quantifiable data to which analysts can apply analytical methods, an approach that is currently missing

from DoDIN-A operations and the intelligence enterprise. These commercial techniques can help address a CTI

shortfall left by a gap in regulations, training, and doctrine. The Army intelligence community can benefit from

using these additional structured analytic techniques to expand the incident management and reporting processes,

thereby enriching data with threat context as operations in the cyberspace domain are further developed.

Integrating structured analytic techniques into cyberspace and intelligence operations sets the stage for

defining requirements for a unified toolset and serves as the basis for standards.

Conclusion

The Army faces continuous competition and conflict in the cyberspace domain; the need for unified reporting

structures and processes further challenges the Army to gain an information advantage. By implementing and

enforcing structured analytic techniques, the Army can better exploit the information from the cyberspace domain

to achieve strategic, operational, and tactical results. Using structured analytic techniques will also drive

requirements for architectural and procedural standards needed to implement viable solutions. NETCOM G-2 is

currently conducting training and implementing analytic techniques to improve network defenses and enhance

incident management and reporting processes. NETCOM G-2 plans to capture their CTI tactics, techniques, and

procedures and share them with the intelligence community. Developing and implementing CTI techniques will

significantly improve the Army's defenses in the cyberspace domain because they enable a more proactive

posture.

Endnotes

1 Government

Accountability Office, Information Technology and Cybersecurity: Significant Attention Is Needed to Address

High-Risk Areas, GAO-21-422T (Washington, DC, 2021), 1, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-422t.

2 Government

Accountability Office, DoD Cybersecurity: Enhanced Attention Needed to Ensure Cyber Incidents Are

Appropriately Reported and Shared, GAO-23-105084 (Washington, DC, 2022), highlights, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105084.

3 Larry G.

Wlosinski, “Cyberthreat Intelligence as a Proactive Extension to Incident Response,” ISACA

Journal 6 (Online Exclusive, November 2, 2021), https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2021/volume-6/cyberthreat-intelligence-as-a-proactive-extension-to-incident-response.

4 Adam Zibak,

Clemens Sauerwien, and Andrew Simpson, “A Success Model for Cyber Threat Intelligence Management

Platforms,” Computers & Security 111 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2021.102466.

5 Figure

adapted from original by author,Joseph Rudell.

6

“ATT&CK,” The MITRE Corporation, accessed June 27, 2023, https://attack.mitre.org/. An open knowledge base of adversary

tactics and techniques based on real-world observations used for developing threat models and methodologies.

7 “Cyber

Kill Chain,” Cyber, Lockheed Martin, accessed June 27, 2023,

https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/cyber/cyber-kill-chain.html. A framework for

understanding an adversary's cyber-attack tactics, techniques, and procedures.

8 Sergio

Caltagirone, Andrew Pendergast, and Christopher Betz, The Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis (Hanover, MD:

Center for Cyber Intelligence Analysis and Threat Research, 2013), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA586960.

Authors

CW2 Travis M. Whitesel is the U.S. Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM) G-2 Regional Cyber

Center Coordinator. He received his appointment as a warrant officer in February 2019 and served as an

all-source intelligence technician for Delta Company, 65th Brigade Engineer Battalion, 2nd Infantry Brigade

Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division. He holds a bachelor’s degree from American Military

University.

Mr. Joseph S. Rudell is a former Department of the Army Civilian Cyber Threat Intelligence Analyst. He led

the NETCOM G-26 Cyber Threat Intelligence Team. He began his Army career in 2008 as a defense contractor

with the Theater Network Operations and Security Center Continental United States (CONUS) performing

intrusion analysis and later overseeing the U.S. Army CONUS sensor grid. He is currently a solutions

integration engineer at the University of Arizona's College of Applied Science and Technology Cyber

Convergence Center.

Contributors

LTC Brian J. Lenzmeier, NETCOM G-2 Analysis and Control Element Chief

CPT Jason L. Scaglione, NETCOM G-2 Analysis and Control Element Deputy Chief

CW2 John W. Becker, Regional Cyber Center-Pacific Intelligence Support Element

CW2 Jeff B. Newsome, Regional Cyber Center-Europe Intelligence Support Element

SFC Trestan Savoy, Regional Cyber Center-Pacific Intelligence Support Element