Soldier Load

The Art and Science of ‘Fighting Light’

By Aaron Childers and CSM Joshua Yost

Article published on: August 1, 2024 in the Fall 2024

Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time:

<22 mins

Soldiers move to their next objective during a Joint Readiness

Training Center rotation at Fort Johnson, LA, on 30 April 2023. (Photo

by SPC Luis Garcia)

When it comes to Soldier load, the Army has a weight problem... not with

Soldiers but with how much they carry. Soldiers in the Army — and

particularly those in the Infantry — carry far too much. Many people

equate Soldier load with the amount you can carry and the length of the

dismounted movement. For example, most Infantry Soldiers think about

ruck-marching standards in terms of the Expert Infantry Badge (EIB)

standard — carrying a 35-pound ruck for 12 miles in under three hours.

As part of Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) Rotation 23-09, 2nd

Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment took a different approach to Soldier

load, and this article will share some of the lessons we learned.

Understanding Soldier load requires leaders to think differently about

dismounted movement. First, leaders need to know what risk is associated

with overloading our Soldiers. Second, leaders need to think differently

about the various types of loads and how to tailor unit equipment loads.

Third, leaders need to consider how to train movement under load for

planning purposes. Lastly, “fighting light” requires a disciplined

approach to resupply operations. Understanding and executing operations

that minimize Soldier load are difficult and take training to conduct

successfully. Despite these challenges, units that master this are

lighter and more lethal.

The Risk Assumed and Who Owns It

Excessive Soldier load for dismounted infantry poses both a risk to

force and a risk to mission. Soldier load is often misunderstood because

leaders don’t understand who really owns the risk trade-off of

overloading Soldiers versus not carrying something you need.

Risk to force is increased by Soldier overload. Fatigue and poor

equipment positioning can offset any advantages to carrying everything

you might need during a patrol, thereby increasing risk to force. “Heavy

loads decrease situational awareness by tilting the head at a downward

angle and increasing the amount of weight that has to be controlled when

a Soldier stops quickly. In controlled experiments, loads have also been

demonstrated to adversely affect shooting response times, increasing the

time it takes soldiers to fire accurately by 0.1 second, relative to

unloaded conditions.”1

In addition to the risk of direct fire contact, the risk of injury, both

during the movement and long term, is compounded by Soldier load.

“Common injuries associated with prolonged load carriage include foot

blisters, stress fractures, back strains, metatarsalgia, rucksack palsy,

and knee pain.”2

Risk to mission is also increased by overloading Soldiers. An increased

load directly impacts the energy Soldiers have available to conduct the

mission once the movement is complete. In other words, if Soldiers use

all their energy on the approach, they will be fatigued on the

objective. “Loads carried on other parts of the body result in higher

energy expenditures: each kilogram added to the foot increases energy

expenditure 7% to 10%; each kilogram added to the thigh increases energy

expenditure 4%.”3

Fatigue and its effect on Soldier performance cannot be understated.

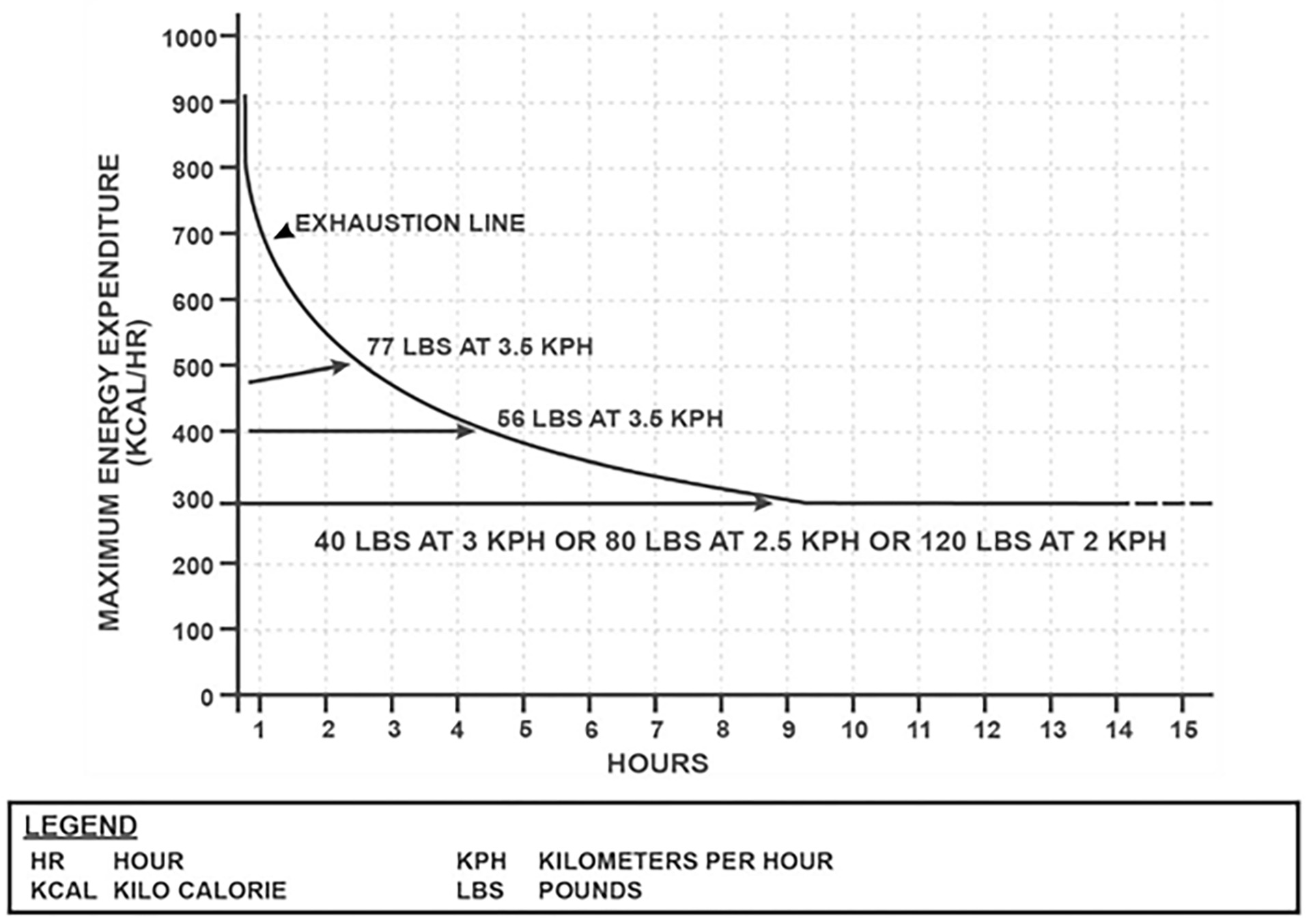

Figure 1 — Maximum Energy Expenditure (ATP 3-21.18, Figure

3-4)

The heavier the load, the less energy a Soldier has to complete the

mission. Fatigue also has a direct negative impact on a Soldier’s

ability to engage targets. In Army studies, “the time required to

determine and acquire a target increased under heavy loads from just

over 3 seconds to more than 3.5 seconds in some configurations, as

accuracy decreased.”4

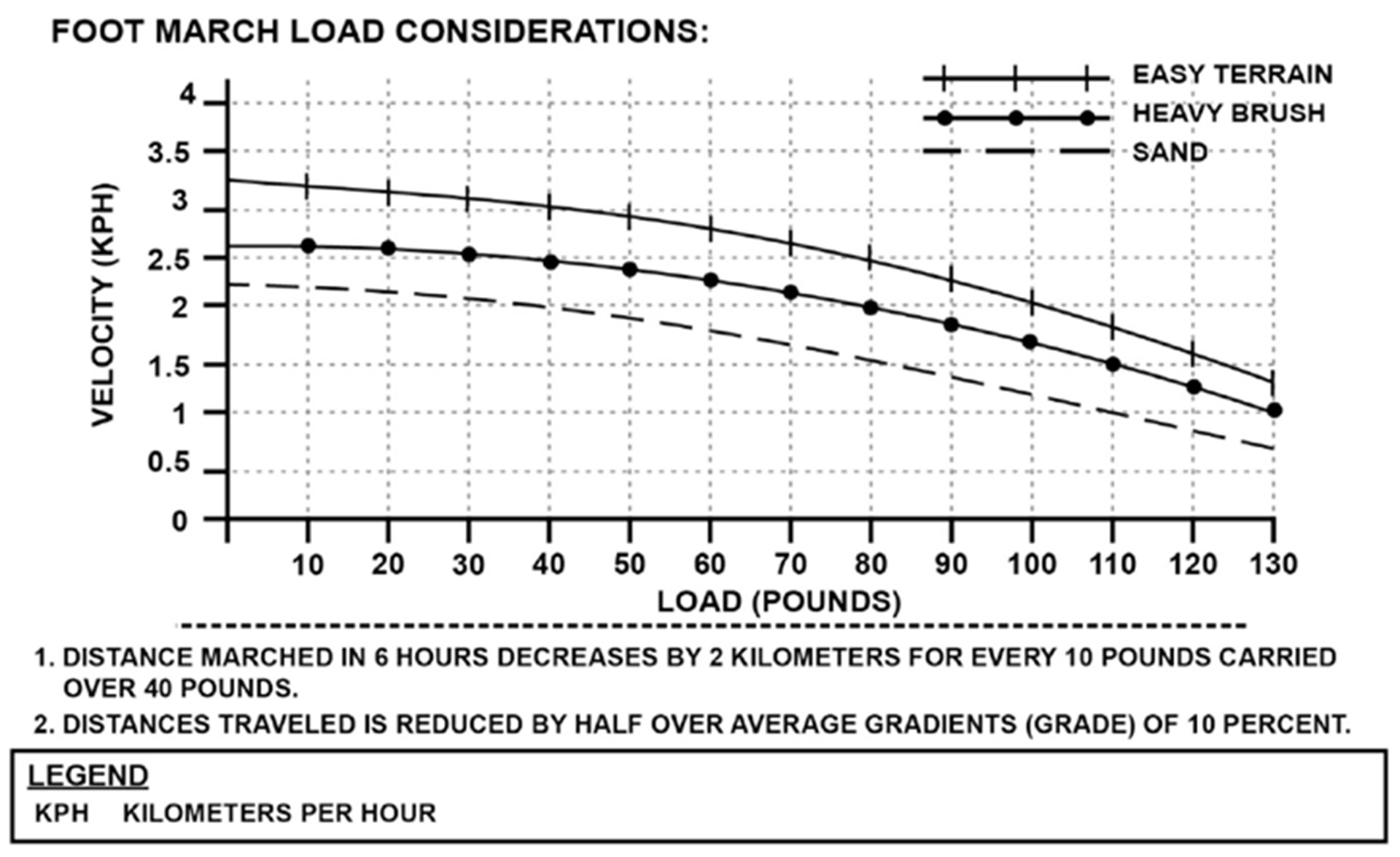

Soldier load impacts the mission beyond the fatigued Soldier being less

able to complete a mission and engage a target quickly and accurately.

Increased Soldier load also increases the risk from a slower speed of

movement. The speed of movement will decrease because of both terrain

and load. The longer a unit is moving, the more it is susceptible to

enemy contact, thus increasing the risk to both force and mission.

Soldier load should be managed by all leaders, and NCO involvement at

the lowest level is the key element to ensuring our Soldiers remain

light and responsive. At lower levels, NCOs are the ones who make the

final checks and ultimately have to deal with the consequences of

overburdening Soldiers. For commanders and their staffs, properly

managing Soldier load can reduce the overall risk to both mission and

force.

The senior enlisted member of the unit is responsible for the packing

list during each training event, but junior leaders should be empowered

to make risk-informed decisions. For company training events, this is

the first sergeant, and for battalion training events, it is the

battalion command sergeant major. Again, leaders at the lowest level

should feel empowered to make decisions regarding Soldier load. Team

leaders and squad leaders are responsible for conducting pre-combat

inspections. If left unchecked, junior Soldiers may take more than

required on a training event for fear that they may need the item. If

layouts are not conducted at the squad and team levels, Soldiers may

inadvertently burden themselves with additional gear, especially in the

winter months.

Ultimately, the commander is responsible overall for the risk associated

with Soldier load. A commander owns the risks to mission and force from

having too heavy a load. This risk is obvious, especially in the summer

months, so commanders at all levels must consider Soldier load in their

planning. For battalion commanders, the military decision-making process

(MDMP) should include Soldier load, and for company commanders, this

should occur during the troop leading procedures (TLPs). At the company

level, commanders and first sergeants must consider Soldier load when

evaluating their own troops as part of METT-TC (mission, enemy, terrain

and weather, troops and support available, time available, civil

considerations), and Soldier load must be revalidated during pre-combat

inspections. Remember, Soldier load INCREASES as orders go down to

companies, platoons, and squads. Leaders must remain engaged to ensure

unnecessary weight is not added.

During MDMP, Soldier load should be specifically evaluated during Steps

2 and 6; it will be owned by the S-4, who will maintain a running

estimate of Soldier load at all times. As part of the S-4’s assessment

during mission analysis (Step 2), the S-4 will display the current

weight with and without water and food (dry weight vs. full weight). As

part of course-of-action (COA) approval (Step 6), the battalion S-4 will

brief the commander on changes to estimated Soldier load when

considering equipment added for that specific COA.

Figure 2 — March Velocity Depletion Based on Load during

Cross-Country Movement (ATP 3-21.18, Figure 3-3)

Table 1 — Example Fighting Load

| ITEM |

WORN ON PERSON |

QTY |

| 1 |

Modular Lightweight Field Load Carrier (with pouches) |

1 EA |

| 2 |

Magazine, 30-round |

7 EA |

| 3 |

Individual First Aid Kit (IFAK) |

1 EA |

| 4 |

Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) with pads and cover |

1 EA |

| 5 |

Gloves, OCIE type |

1 PR |

| 6 |

Ballistic eye protection (APEL approved) |

1 EA |

| 7 |

ID card |

1 EA |

| 8 |

ID tags with chains (long and short) |

1 SE |

| 9 |

Note-taking material |

1 SE |

| 10 |

Flashlight with red color lens |

1 EA |

| 11 |

Hearing protection |

1 EA |

| 12 |

Watch |

1 EA |

| 13 |

M4 Blank Adapter |

1 EA |

| 14 |

Combat uniform (OCP) |

1 EA |

| 15 |

Cap, patrol with rank and name tape |

1 EA |

| 16 |

Assigned weapon |

1 EA |

| 17 |

Night vision |

1 EA |

Table 2 — Example Approach Load

| ITEM |

RUCKSACK DESCRIPTION |

QTY |

| 1 |

Rucksack |

1 EA |

| 2 |

2-quart canteen |

1 EA |

| 3 |

Entrenching tool (E-Tool) |

1 EA |

| 4 |

Socks |

4 EA |

| 5 |

Shirt, brown |

1 EA |

| 6 |

Hygiene kit (72 hours) |

1 SE |

| 7 |

*Razor, shaving cream, toothbrush, toothpaste |

|

| 8 |

Bivvy cover |

1 PR |

| 9 |

Parka, wet weather w/rank |

1 EA |

| 10 |

Poncho/rain fly |

1 PR |

| 11 |

Poncho liner |

1 PR |

| 12 |

Weapons cleaning kit |

1 EA |

| 13 |

Canteen, 1-quart |

2 EA |

| 14 |

Hydration system (CamelBak) |

1 EA |

| 15 |

Meal, ready to eat (MRE) (field stripped) |

6 EA |

| 16 |

Baby wipes |

1 EA |

| 17 |

Sunblock |

1 EA |

| 18 |

Bug repellent |

1 EA |

Table 3 — Example Team Bag

| ITEM |

TEAM BAG |

QTY |

| 1 |

Army Combat Uniform (top/bottom) |

1 SE |

| 2 |

Boots, tan/brown (AR Army Regulation 670-1) |

1 PR |

| 3 |

Socks, boot, black/green |

4 PR |

| 4 |

Undershirt, tan/brown |

4 EA |

| 5 |

Personal hygiene kit (1 week) |

1 SE |

| 6 |

Improved Outer Tactical Vest (IOTV) with plates |

1 EA |

| 7 |

Protective mask |

1 EA |

Dictating the steps of MDMP where Soldier load is discussed may seem

proscriptive, but this is essential to ensuring leaders remain aware of

what we are asking Soldiers to carry. This responsibility does not end

with planning — it continues into execution. The staff shares

responsibility for Soldier load. The battalion S-4 must remain cognizant

of the amount of ammunition and meals a Soldier is carrying during

operations. Ammunition, water, and meals are the heaviest items carried

by Soldiers, and staff officers must remain aware of what they are

asking Soldiers to carry. Water is not negotiable, but food and

ammunition are variables that can be controlled by the battalion S-4.

Resupply capabilities, discussed later in this article, are ways to

minimize the amount a Soldier is carrying. Hot meals brought forward not

only decrease the risk of hot and cold weather injuries but also

decrease the amount of food a Soldier is required to carry.

The Individual Soldier’s Combat Load

We need to redefine what the term Soldier’s load really means. It is

often misunderstood, as in the EIB example, to indicate what Soldiers

have in their ruck, but what Soldiers are carrying is again far more

complicated than just what is on their back. We need to understand

everything included in Soldier load and also comprehend what a realistic

goal would be. With this in mind, we can redefine what we expect a team,

squad, and platoon to carry, as unit equipment quickly adds up across

Soldiers.

Soldiers are not only carrying what is in their rucksack, but they also

have all of their individual equipment, weapon, position-specific gear,

and radios. To just look at what someone is “carrying” does not give a

complete picture of the demands we are placing on Soldiers, nor does it

help us understand what can be removed to ease Soldier load. In their

recent report for the Center for New American Security, Paul Schaffer

and Lauren Fish attempted to better define what constitutes Soldier

load:

Fighting load consists of the equipment (weapon, ammunition, helmet,

body armor, water, etc.) that Soldiers carry directly on their person

when maneuvering and fighting.

Approach load consists of the fighting load plus a rucksack carried

during a march, which would contain additional water, ammunition,

food, and other supplies for the duration of the mission.5

Another way to look at the definitions above is to look at the fighting

load as everything a Soldier would carry onto an objective from the

objective rally point (ORP). The approach load is everything a Soldier

would carry to the ORP, which includes the fighting load. This

definition not only accounts for all the weight a Soldier carries, but

it also puts the items carried in an operational framework.

Tables 1-3 show an example packing list used by 2-30 IN during our

August 2023 JRTC rotation and include the fighting load, approach load,

and a team bag, which will be discussed later. The packing list is

designed to get a Soldier through an entire 10-day summer rotation and

has a dry weight of under 25 pounds per ruck. Additional combat load,

even for medics and those carrying special equipment, did not exceed 55

pounds. Two main factors contributed to the “lightfighter” load. One,

this packing list is dependent on access to company trains within 24

hours, and two, this packing list will vary depending on METT-TC

requirements, especially weather.

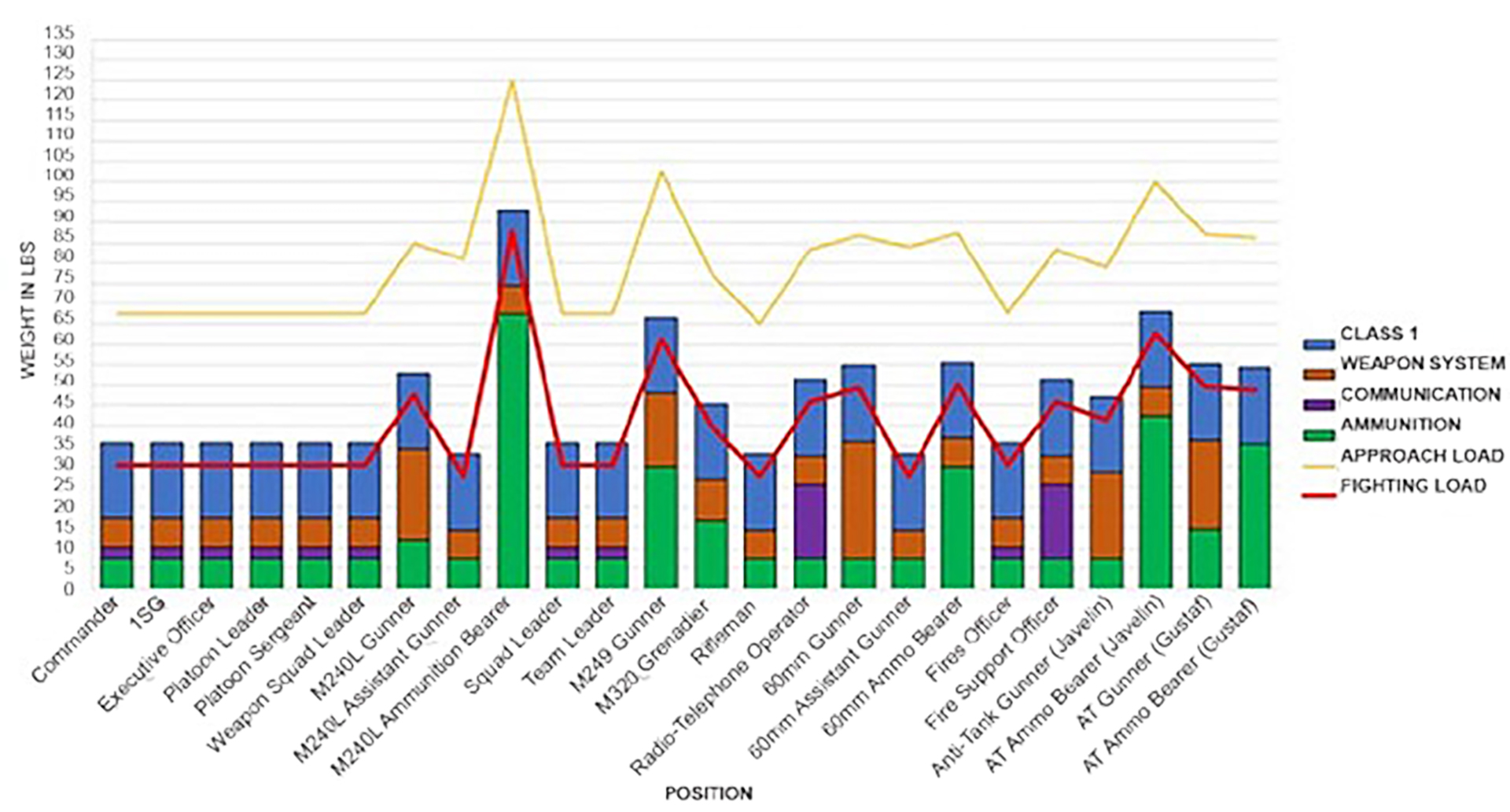

Figure 3 — Analysis of All Weight Carried (including Weapon System)

Using 2-30 IN JRTC 23-09 Packing List

The use of the team bag is essential. Company trains give a unit the

flexibility to put items not needed during the approach onto company

trains and move them forward when needed.

The one missing variable is the inclusion of equipment for each person

by position. The main contributor to remaining weight is ammunition,

followed by batteries. This can vary greatly by position; for example, a

radio-telephone operator (RTO) might carry little ammunition and a

relatively light M4 but may carry multiple batteries. Conversely, a

machine gunner may transport few radio batteries but carries the most

weight when considering the weight of the ammunition and weapon. Again,

this requires leaders to make informed decisions and accept risk.

Infantry leaders often consider carrying the entrenching tool (E-tool)

as a “must-have.” However, if you consider machine gunners, Soldiers who

carry an extremely heavy load and are always behind their weapon (and

thus never dig their own position), the question turns into whether or

not they actually need an E-tool. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of

weights by position when merging the above packing list with weights of

batteries, weapons, and the other items required for their duty

assignment.

Soldier load is often inadvertently increased because of requirements

for special equipment at echelon, and leaders must limit the amount of

this equipment to reduce the amount of weight individuals are carrying.

Special equipment at the team level may be duplicative when operating as

a platoon. For example, wire cutters carried by a team for a squad

patrol should not result in six wire cutters going out on a

platoon-sized patrol. Managing special equipment takes leader

involvement, and Soldier load can be reduced by only carrying the

minimum equipment required for a mission. As stated previously, junior

leaders should feel empowered to make decisions on what is carried. The

uniform should fit the requirements of the mission. Tables 4-6

specifically look at special equipment by organizational level and

eliminate redundancy at echelon.

Table 4 — Special Equipment for the Infantry Team

| Traditional Special Equipment |

Suggested Lightfighter Special Equipment |

Aid and Litter

- Skedco

- Aid bag

- Helicopter landing zone (HLZ) kit

-OR-

Breach

- Shotgun

- Wire cutters

- Hooligan tool

-OR-

- Flexcuff

- Enemy prisoner of war (EPW) tag kit

-OR-

Demo

- Demolitions

- Det cord

- M88 & shock tube

Additional items:

- M249 spare barrels

|

Aid and Litter

- Skedco

- Aid bag

- HLZ kit

-OR-

Breach

- Shotgun

- Bayonet

-OR-

- Flexcuff

- EPW tag kit

-OR-

Demo

- Only when required

|

Table 5 — Special Equipment for the Infantry Squad

| Traditional Special Equipment |

Suggested Lightfighter Special Equipment |

Aid and Litter

- 2x Skedco

- 2x Aid bag

- 2x HLZ kit

Breach

- 2x Shotgun

- 2x Wire cutters

- 2x Hooligan tool

EPW

- 2x Flexcuff

- 2x EPW tag kit

Demo

- 2x Demolitions

- 2x Det cord

- M88 & shock tube

Other items:

- Batteries

- M249 spare barrels

|

Aid and Litter

- 1x Skedco, 1x Poleless litter

- 2x Aid bag

- 1x HLZ kit

Breach

- 1x Wire cutters

- 1x Bayonet

EPW

- 2x EPW tag kit

Demo

- Only when required

Other items:

- Batteries

|

Table 6 — Special Equipment for the Infantry Platoon

| Traditional Special Equipment |

Suggested Lightfighter Special Equipment |

Aid and Litter

- 6x Skedco

- 6x Aid bag

- 6x HLZ kit

Breach

- 6x Shotgun

- 6x Wire cutters

- 6x Hooligan tool

EPW

- 6x Flexcuff

- 6x EPW tag kit

Demo

- 6x Demolitions

- 6x Det cord

- M88 & shock tube

Other items:

- Batteries

- M249 spare barrels

- 2x Thermal sights for M240

- 2x Tripod

|

Aid and Litter

- 2x Skedco, 3x Poleless litters

- 6x Aid bag

- 1x HLZ kit

Breach

- 1x Shotgun

- 2x Wire cutters

- 2x Bayonet

EPW

- 3x Flexcuff

- 3x EPW tag kit

Demo

- Only when required

Other items:

- Batteries

- 2x Thermal sights for M240

- 2x Tripod

|

Decisions of what not to carry should be made by informed leaders, even

at the team leader level. Even in these examples, additional changes can

be made. For example, machine gunners may not need to carry E-tools, and

their assistant gunners can carry one tool for both of them. Leaders

must think intentionally of creative ways to limit weight.

Training for Soldier Load

When training for long-distance movement, leaders should not fall into

the trap of just carrying heavy loads over extended distances. Instead,

training should replicate patrolling rather than preparing for an EIB

ruck march. Similarly, at every available opportunity, units should

train on dismounted sustainment. Once a unit goes light, one of the

hardest challenges will be sustaining the dismounted force.

When training for dismounted movements, leaders should focus on

perfecting their movement rates, rates of march, movement formations,

and actions at halts. These are essential for a dismounted element away

from supply lines.

Controlling the rate of march is vital to ensuring dismounted Soldiers

can sustain tempo when attacking an objective. Even with the lightest of

loads, an uncontrolled rate of march will fatigue units, making Soldiers

combat ineffective. The rate of march should be controlled by leaders at

all levels and determined in accordance with the standards set forth in

Army Techniques Publication Foot Marches.

Understanding halt timelines is also essential. For dismounted infantry

movements, units will “halt for 15 minutes during the first hour [of

movement] and 10 minutes every 50 minutes thereafter.”6

This pace can be adjusted by leaders at all levels according to mission

requirements. Ensuring halts are executed ensures that Soldiers are not

only able to close short distances but are also able to close long

distances over extended periods of time. During the first hour’s long

halt, units should check Soldier equipment and adjust or redistribute it

as necessary. During this halt, and all following halts, Soldiers will

maintain security while consuming water and food. Doing this will help

Soldiers maintain energy levels. Leaders will conduct foot checks as

required. During halts, the formation will conduct actions normally

associated with long halts, to include establishing hasty sectors of

fire, performing maps check, repositioning casualty-producing weapons

(M240), and conducting a hasty emplacement of mortars.

Halts should be planned whenever possible and exhibit characteristics

similar to that of a patrol base (a site that is easily defendable for

short periods of time, away from natural lines of drift and high-speed

avenues of approach, provides cover and concealment from both ground and

air, and provides little to no tactical advantage to the enemy,

according to the Ranger Handbook, Training Circular 3-21.76).

Planning should be associated with a movement control measure,

specifically a planned checkpoint, or a phase line.

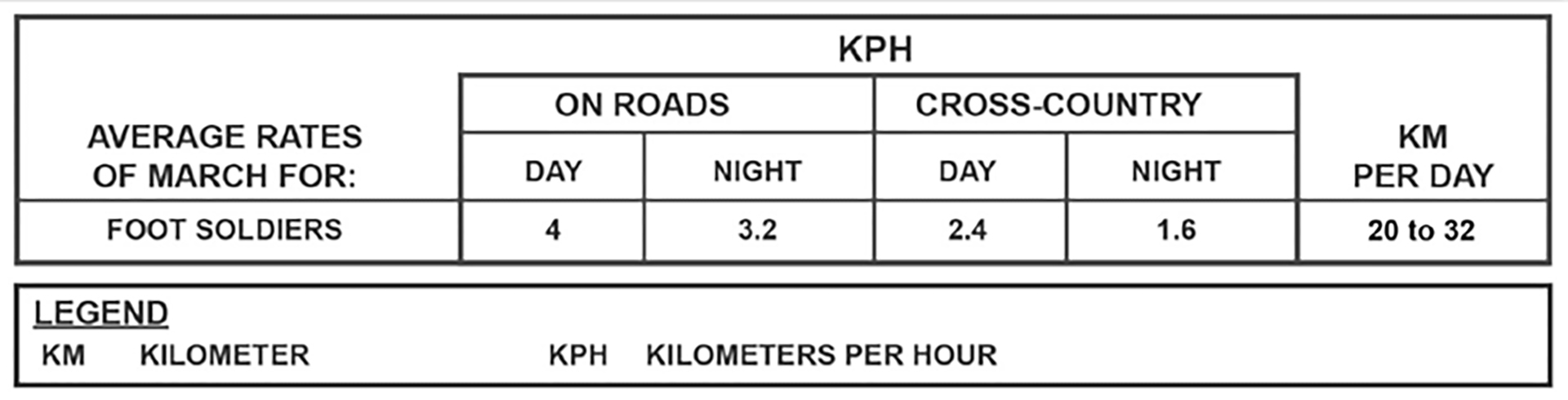

Movement rates through restrictive terrain should plan for a light

infantry company to move at 2 kilometers per hour (kph) during the day

and 1 kph at night. Although this is a generally accepted rule, route

planning is the largest factor of a steady rate of march. Keeping

Soldier load light helps Soldiers cross this distance more efficiently.

Achieving 20-32 kilometers per day is only possible when Soldier load

and rate of march are combined effectively.

Route planning should avoid moving through restrictive terrain except

when the tactical situation requires. Slope, vegetation, and hydrology

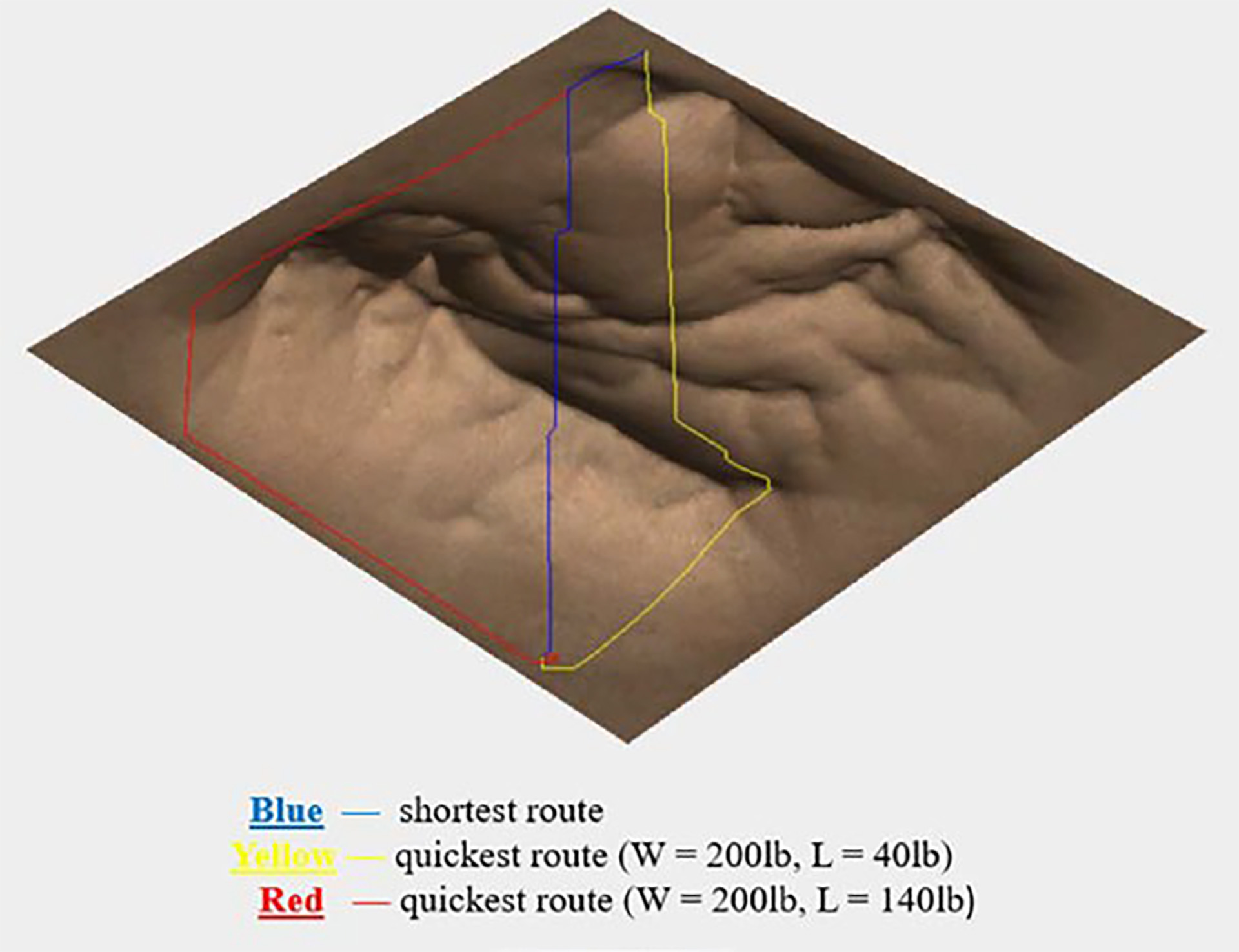

should all be taken into consideration when planning routes. Current

computer modeling shows the impact of terrain on movement speed for a

Soldier moving under 40-pound and 140-pound loads. For light infantry to

utilize restrictive terrain for tactical advantage, both Soldier load

and route planning must be considered.

Figure 4 — Average Dismounted Rates of March (ATP 3-21.18, Figure

3-2)

Figure 5 uses computer models to show the fastest route over specific

types of terrain when a 200-pound individual conducts movement over

restrictive terrain. The goal for leaders should be to achieve the

yellow line. This route combines a lighter Soldier load with a shorter

and more tactically advantageous route. The lighter load allows for the

dismounted Soldier to better utilize restrictive terrain, thus providing

a perceived tactical advantage.

Movement formations and techniques are of special consideration for

dismounted movements under load. The wedge and the column remain the

fastest formations, with the wedge maintaining the highest level of

security. The modified column and the column should only be used when

the terrain does not allow for the wedge. Although traveling and

traveling overwatch are considered the fastest movement techniques, the

bounding overwatch formation gives Soldiers a chance to rest while

providing security. Leaders should consider the bounding overwatch

technique to maintain security when movement must be maintained but

Soldiers are showing signs of fatigue.

Figure 5 — The Effects of Load on Route Selection7

Dismounted Resupply

Dismounted resupply is one of the most difficult aspects of operating as

light infantry. It involves the transfer of equipment from a logistical

element to the dismounted fighting Soldier. A vehicle cannot simply move

right up to a dismounted location. It takes planning, and the transfer

from a vehicular or air platform to a dismounted resupply team must be

rehearsed. “Fundamentally, only two great novelties have come out of

recent warfare. They are: (1) mechanical vehicles, which relieve the

Soldier of equipment hitherto carried by him; (2) air supply, which

relieves the vehicle of the road.”8

Resupply is essential to “lightfighting.” Without sustained water, food,

and ammunition, light infantry units cannot operate for extended periods

of time. To remain resupplied, light infantry units should remain

innovative, adaptable, and disciplined. There are multiple ways to

resupply dismounted infantry units, including the use of company trains,

a dismounted duty platoon, speedballs, caches, and aviation elements.

Company trains remain the main method of resupply for company-level and

below dismounted movements. As a planning factor, company trains should

remain at least one terrain feature away from combat formations and out

of direct fire contact. In a light infantry formation, the company

trains may only consist of two vehicles: the commander’s High Mobility

Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV) and the company Light Medium

Tactical Vehicle (LMTV). When operating in restrictive terrain, the

company all-terrain vehicle may also be utilized to transport equipment

between the location of the LMTV and the company patrol base. The

company executive officer (XO) oversees resupply as the first sergeant

moves with the formation. This is not a rigid requirement but a planning

consideration that leaders can adjust.

Dismounted resupply is the only organic method that can traverse through

restrictive terrain. The company patrol base is usually located in

restrictive terrain where the LMTV cannot conduct tailgate resupply.

Companies should designate a platoon to conduct resupply operations. The

first sergeant is responsible for conducting resupply from the trains

forward to the company. As previously mentioned, duty platoons with the

right equipment can assist with resupply. This will require one platoon

to reduce the amount of personal equipment its Soldiers are carrying in

order to carry supplies (especially Class I, III, and IV). This allows a

dismounted element to move forward without bringing up company trains.

The increased load of these classes of supplies, however, fatigues the

troops assigned with this duty and may make them combat ineffective for

the current operation.

Speedballs are a colloquial term used to describe prepackaged resupply

bundles. These supplies are meant to quickly resupply at the point of

need and usually consist of Class I, II, III, IV, and V. In contact,

Class I and V will be the most emergent needs. These items are packaged

in duffle bags or body bags and pre-staged at the brigade support area.

During mission planning, the battalion S-4 should coordinate between the

companies and the forward support company to configure these items. Also

key to using speedballs is the need to track their location so they can

be loaded onto waiting trucks or aircraft. The battalion XO or commander

is usually the release authority for sending speedballs forward to

troops.

Caches are another form of resupply not commonly used. “Caching is the

process of hiding equipment or materials in a secure storage place with

the view to future recovery for operational use.”9

Caches are another way to lighten Soldier load and require prepositioned

supplies to be staged forward. The key element of a cache is that the

supplies are left hidden and unsecured until the receiving unit secures

them. In order to properly cache an item, two elements — the placing

unit and the receiving unit — are tasked to conduct the caches. The

placing unit could be a scout element, an aviation element dropping

supplies, or a vehicle trailer that was placed in the woods. The

receiving element is usually larger and unable to resupply internally.

The danger with caches is that an enemy element could find the cache and

either take the supplies or ambush friendly forces when they come to

retrieve the supplies. Key to the cache is properly marking the

location, communicating this location to a higher element, camouflaging

the equipment, and taking steps (like deception) to ensure enemy forces

do not find the location.

Aviation elements have a unique advantage in conducting resupply

operations. For a dismounted resupply, there are two main types of

resupply conducted by aviation elements. Low-cost, low-altitude (LCLA)

resupply involves dropping supplies from a rotary-wing or fixed-wing

aircraft. LCLA requires coordination between the battalion and the

aviation element. This requires pre-coordination to ensure that the

resupply takes place in a timely manner. Units may also require a

jumpmaster and pathfinder to assist the aviation element in dropping

supplies. There are two main challenges of LCLA. First, while preplanned

LCLA drops are an effective way to conduct resupply, LCLA is not

especially flexible to the needs of “lightfighters.” Second, parachutes

do not always land where planned. A resupply package drifting off course

can increase the amount of time before the resupply and risk being

compromised by the enemy.

Sling loads are resupply packages moved underneath rotary-wing assets.

UH-60s and CH-47s can sling various packages across all classes of

supply. Sling loads are reliable and can place supplies in an accurate

location. The drawbacks of sling loads are the equipment required to

sling and the shortage of trained personnel to rig resupply. Again, it

takes practice to get crews proficient in rigging resupply bundles. An

additional drawback is that rotary-wing assets can give away positions

if drop locations are not properly planned.

Soldiers in 2-30 IN move to Peason Ridge training area to conduct

situational training exercises at Fort Johnson, LA, in January 2023.

(Photo courtesy of 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain

Division)

Finally, water resupply is the most pressing need for a dismounted rifle

company, especially during warm weather. There are several ways to

conduct water resupply, but all come at a cost. Water purification, if

acceptable at a unit’s location, can solve this problem, but purifying

water takes time, requiring a unit to stop movement. Purification

tablets are also an option, but these may not filter out heavy metals

and all toxins, and again, are one more item a Soldier must carry. Each

rifle company has a 400-gallon water “buffalo” capable of resupplying a

rifle company. However, this also needs to be rehearsed. Even for a

well-rehearsed company, resupplying callbacks, or water gallons, can

take more than an hour.

Conclusion

Soldier load is not a simple problem that can be easily solved or viewed

as merely weight and distance. Army leaders must understand the risk in

overloading Infantry Soldiers. The asymmetric advantage of light

infantry is the ability to move through restrictive terrain to gain a

decisive advantage over the enemy. This mobility gives them the ability

to capitalize on the principles of the offense, specifically surprise

and audacity. Without managing Soldier load, a light infantry formation

loses all principles of the offense, and this adversely impacts tempo

and increases risk to the force and mission. In short, a lighter force

is a more lethal force. We have to rethink how we view Soldier loads and

must look at approach and fighting loads in a different light. Managing

Soldier load must be done by adhering to the packing list, understanding

the compounding impacts of adding weight requirements at echelon,

ensuring that rate of march supports Soldier load efforts, and

conducting efficient dismounted resupply. This is a leader business, and

the success of America’s fighting Soldiers depends on maintaining the

“lightfighter” mindset.

Endnotes

1. Lauren Fish and

Paul Scharre, “The Soldier’s Heavy Load,” Center for a New American

Security (En-US),

www.cnas.org/publications/reports/thesoldiers-heavy-load-1.

2. Joseph J. Knapik,

Katy L. Reynolds, and Everett Harman, “Soldier Load Carriage:

Historical, Physiological, Biomechanical, and Medical Aspects,”

Military Medicine, January 2004,https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14964502/.

3. Ibid.

4. Fish and Scharre,

“The Soldier’s Heavy Load.”

5. Ibid.

6. Army Techniques

Publication 3-21.18, Foot Marches, April 2022.

7. Jeremiah M.

Sasala, “Individual Soldier Loads and The Effects on Combat

Performance,” (Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, 2018),

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1060058.pdf

8. S.L.A. Marshall,

The Soldier's Load and the Mobility of a Nation (Quantico,

VA: The Marine Corps Association, 1950).

9. Training Circular

31-29, Special Forces Caching Techniques (discontinued).

Author

LTC Aaron Childers, an Infantry officer, is currently

the G-3 for the 10th Mountain Division. He previously commanded 2nd

Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th

Mountain Division, Fort Johnson, LA. His previous assignments include

serving with the 82nd Airborne Division, 1st Cavalry Division, 101st

Airborne Division (Air Assault), the Joint Staff, and the Army Staff.

He is also a member of the Military Writers Guild.

CSM Joshua Yost currently serves as the command

sergeant major of 2-30 IN. His previous assignments include serving

with the 75th Ranger Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Ranger Training

Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, Asymmetric Warfare Group, and U.S.

Army Japan.