Relearning Infiltrations

The Light Infantry Advantage

By LTC Aaron Childers and MAJ Michael Stewart

Article published on: August 1, 2024 in the Fall 2024 Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time: < 11 mins

(Illustration from photo by Paolo Bovo)

Over the last two years, much attention has been given to the destruction of Russian tanks by Ukrainian forces as

part of the ongoing war between the two nations. As of 19 February 2024, more than 2,742 tanks had been

destroyed, and images of these destroyed vehicles have become a hallmark of the conflict.1 Ukrainian forces received Javelin anti-tank

missiles from the U.S. early in the conflict, and their use has been overwhelmingly successful, raising the

weapon to an almost exalted status. However, little attention has been paid to the tactics which enabled the

Ukrainian forces to be so successful behind and within Russia’s forward line of own troops (FLOT). To gain an

advantage over their Russian adversaries, Ukrainians utilized infiltrations to create multiple dilemmas in

depth.2

In U.S. doctrine, forms of maneuver, which consist of envelopment, frontal attack, infiltration, penetration,

and turning movement, “are distinct tactical combinations of fire and movement with a unique set of

characteristics that differ primarily in the relationship between the maneuvering force and the enemy.”3 This relationship describes

offensive and defensive operations as the overarching concept for courses of action to gain identified decisive

points or positions of advantage.4

Of these forms of maneuver, infiltrations hold a particular advantage in current conflict as they are designed

to move forces deeper into enemy-controlled areas to accomplish a unit’s tasks. Infiltrations have utility

during both offensive and defensive operations, allowing light infantry formations to use restrictive terrain as

an advantage. Although difficult to train, they offer a decided advantage to units that employ them in

conjunction with other forms of maneuver or to create tactical opportunities.

The Misunderstood Form of Maneuver

The infiltration is often misunderstood, and therefore, not something units in the U.S. Army often train or

execute during combat training center (CTC) rotations. Units will commonly execute an envelopment (the preferred

form of maneuver) or even a frontal attack (the least preferred but easiest to control), but seldom do units

conduct a textbook infiltration.

As described in Field Manual (FM) 3-90, Tactics, “an infiltration is a form of maneuver in which an attacking

force conducts undetected movement through or into an area occupied by enemy forces. Infiltration is also a

march technique used well before encountering enemy forces to avoid enemy information collection assets.”5 Army doctrine does a good job of

describing infiltrations in both FM 3-90 and in subordinate infantry battalion and company manuals; however,

they are not often employed as they are difficult to execute and often viewed as risky for commanders at

echelon.

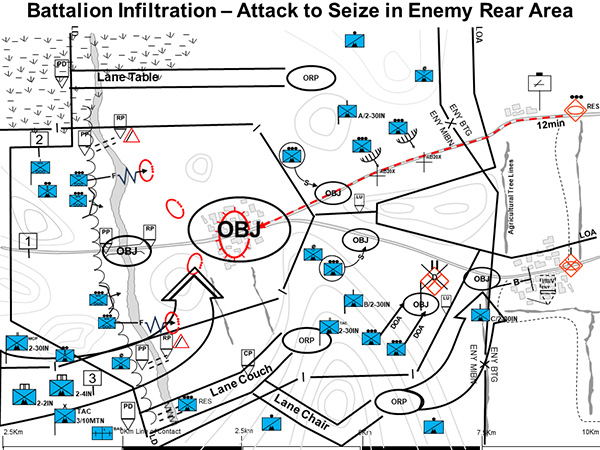

Figure 1 — Battalion Infiltration - Attack to Seize in Enemy Rear Area

In Ukraine, advancements in unmanned aerial systems (UAS), combined with accurate fires assets, have made larger

scale maneuver untenable for long durations. Envelopments require large unit formations to be able to mass for

attacks. As seen in attacks like the Russian wet gap crossing of the Siversky Donets River on 8 May 2022, large

concentrations of forces at points of penetration or narrow axes of advance are often met with massive artillery

attacks.6 Such consequences require

units to move in smaller, less detectable formations. For light infantry, who are particularly susceptible to

artillery, utilizing infiltrations is not just important for mission success but necessary for unit survival.

Detection means death; some Ukrainian forces have indicated that once a Russian UAS sees them, “they have as

little as three minutes before indirect fire is called in on their location.”7 The same has proven true for Russian forces, who

were shown in an October 2023 video released by Ukraine to be targeted by cluster munitions. For light infantry,

success and survival in the UAS era depend on a tactical unit’s ability to create dispersion to avoid detection

while retaining enough combat power to create dilemmas in depth.

The Multi-Tool of Maneuver

Infiltrations are an extremely versatile form of maneuver, as once behind the FLOT, they can be utilized in the

offense, the defense, and to make enemy positions untenable. Again, these operations take training, risk

acceptance, and understanding from subordinate commanders to work effectively. If successful though, a formation

behind an enemy’s FLOT can not only cause irreparable damage but also impact the enemy’s decision-making process

in a way that is advantageous for the infiltrating unit’s higher tactical or operational headquarters.

As described in FM 3-90, “infiltrations are used to set the conditions for larger operations as a part of the

overall scheme of maneuver.”8 With a

friendly force forward of the FLOT, these units can set the conditions for larger operations while

simultaneously causing multiple dilemmas for the enemy. Units can seize key crossings and bridges for a larger

force to cross from unexpected directions while simultaneously causing the enemy to deploy forces early by using

ambushes and spoiling attacks to protect the friendly main effort. Finally, infiltrations can position friendly

forces to make enemy strongpoints displace or make them untenable. By positioning large assets to the rear of a

strongpoint, forces can disrupt enemy resupply or make the enemy withdraw. This occurred during Joint Readiness

Training Center (JRTC) 23-09, where 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment faced a mechanized enemy strongpoint

to the southeast. Previous attempts to seize the strongpoint had failed, and the enemy continued to resupply

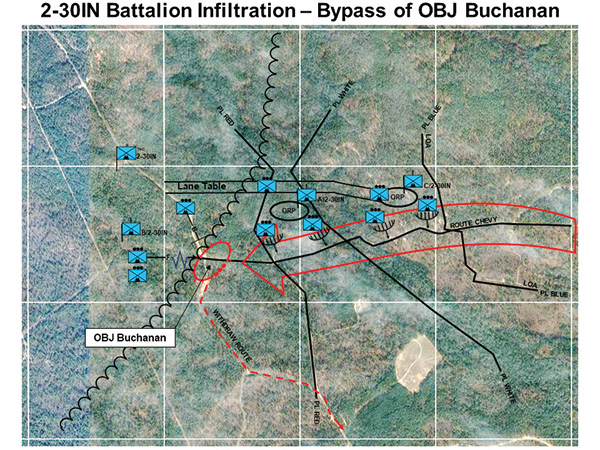

along Alternate Supply Route (ASR) Chevy (see Figure 2). By infiltrating two companies forward of the FLOT, and

along ASR Chevy, the enemy position was no longer tenable and they withdrew.

Figure 2 — Battalion Infiltration - Bypass of Objective Buchanan

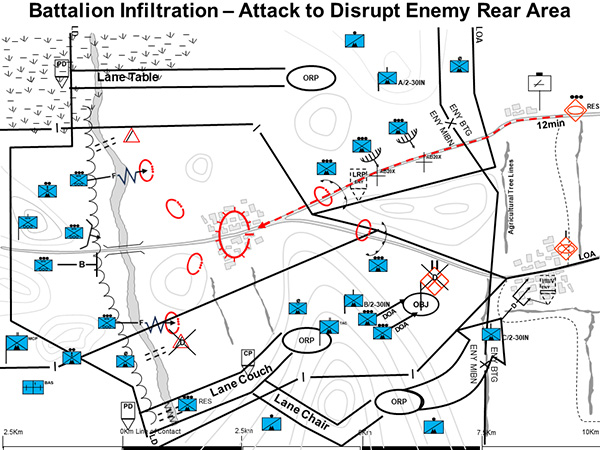

Expanding on the utilization of infiltration in the offense, operations not in conjunction with other units or

forms of maneuver can achieve effects and present opportunities to exploit. In this sense, the use of

infiltrations allows friendly forces to establish an area of operations for small unit actions forward of the

FLOT that do not support an immediate higher headquarters operation. For example, if a company moves behind the

enemy’s FLOT, it could launch ambushes along key supply points, specifically against armored formations, as we

have seen in Ukraine. A headquarters forward of the FLOT can also provide intelligence, conduct raids, or

conduct other harassing attacks. These variations of attack, reconnaissance, and security operations enable

friendly forces to disrupt the enemy’s decisionmaking cycle to create opportunities for other operations. This

is not about just being a nuisance; the successful use of infiltration should require the enemy to commit

additional resources to counter friendly actions or give the impression that a much larger force is present.

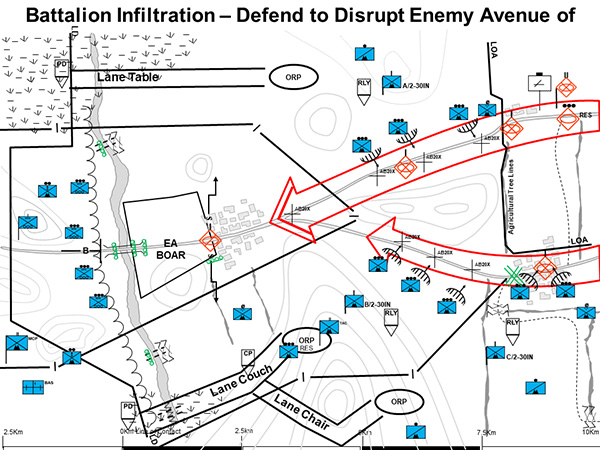

The benefits of an infiltration are not limited to the offense. The light infantry defense is often overlooked as

a security operation in favor of traditional, larger engagement area-type defenses common to combined arms

battalions. However, small units are particularly suited to infiltrate forward of the FLOT in order to set up

multiple ambushes along key avenues of approach. By moving small elements into position early and forward of a

traditional engagement area, friendly forces have the ability to organize and conduct variations of attacks,

especially on high-value targets such as armor and engineering assets. This early employment by small forces can

successfully disrupt attacking forces long before they arrive at a main engagement area. This has the added

benefit of slowing formations so they are susceptible to friendly air and artillery assets. Spoiling attacks at

enemy assembly areas are also a practical use for forces who have successfully infiltrated the enemy’s rear.

Figure 3 — Battalion Infiltration - Attack to Disrupt Enemy Rear Area

Infiltrations Play to the Strengths of Light Infantry

Light infantry forces are specifically suited to conduct infiltrations due to their ability to conduct

dismounted movement through restrictive terrain, move with minimal signature, and minimize logistical

requirements. Mechanized and motorized forces are tied to roads, especially in portions of Europe where the

spring thaw prevents movement on all but the best road networks. Enemy sensors, like the UAS platforms used by

Russian forces in Ukraine, will monitor movement along key routes.9 For light infantry, the movement through

restrictive terrain, such as steep or marshy terrain, increases the likelihood that a friendly formation can

move behind the FLOT undetected. Once a formation is established behind the FLOT, restrictive terrain hides

patrol bases or command posts until the friendly unit decides to attack. Again, restrictive terrain will assist

a dismounted unit moving back into a rally point without being followed.

Thus, key to not being tracked is a light infantry unit’s ability to minimize its signature by maximizing

terrain where other units cannot or will not enter.

Along with movement through restrictive terrain, light infantry units have the ability to minimize their

signature and reduce the likelihood of detection. When conducting movement, these formations could separate into

smaller units for movement. For example, infiltration lanes should not become a “dismounted highway” for

movement, but care should be given to the size of the element moving along the lanes. A battalion should

identify different lanes for each company, and, unless specified, a company can subdivide into platoon movement

formations along distinct movement lanes. Subdividing into smaller organizations minimizes the possibility that

a unit will be detected, and if it is detected, it increases the probability that an enemy force would decide

not to dedicate artillery assets on such a small element as this would make their own guns susceptible to

identification and counter-battery with a relatively low payout. It is unlikely that a dismounted platoon would

exist as an enemy’s value target, so this pushes the decision calculus in favor of friendly forces. A light

infantry formation has an advantage in restrictive terrain, but it should evaluate all methods of possible

contact, including electronic detection.

Figure 4 — Battalion Infiltration - Defend to Disrupt Enemy Avenue of Approach

Finally, light infantry formations, if trained properly, can have a minimal logistical footprint. Although

difficult to train, light formations can operate for extended durations with limited logistical resupply. When

resupply is needed, light formations can conduct dismounted resupply at the company level. Additionally, water

resupply, which is traditionally one of the limiting factors in dismounted movement, can be extended with water

filters down to the squad level. Food, batteries, and ammunition can either be resupplied piecemeal through

dismounted movement, small UAS, or air. Again, this takes extensive practice but can allow for light infantry to

remain forward for extended periods and achieve sustained effects on objectives.

Hard to Train

To become proficient at infiltration requires specific training. Infiltrations can be challenging to

successfully execute and require units to become proficient at long dismounted movements, conduct communications

training, complete specific training with enablers, and execute rehearsals for logistics.

As a basic building block, units that want to succeed at conducting infiltrations must excel at dismounted

movement under load and over time. The foundation of moving forward of the FLOT is being able to move far enough

forward that you are in an enemy’s operating area. This requires movements of 10 kilometers or more through

restrictive terrain, a distance that requires careful consideration into Soldier load and unit equipment. A unit

conducting these types of operations, especially in mountainous or marshy terrain, must be able to move light.

To train for this, a unit must do more than just conduct long distance movements as part of morning physical

training. Soldiers and leaders must understand Soldier load, movement rates, and rest periods. Units should

practice moving through the brush, taking halts, and patrolling techniques in both day and low visibility and

under a variety of weather conditions

Another element that is difficult for units to train is radio communications, both control of radio

communications during operations and mastery on different radio types. During infiltrations, units are

susceptible to detection if the enemy can identify radio traffic on the electromagnetic spectrum. Utilizing

communication windows and formatted reports to minimize radio traffic takes practice. This discipline requires

both proper use of the radio systems themselves and practice communicating without using radios. To talk at the

distance required for infiltrations, units must use nonstandard dismounted radio antennas including dismounted

OE254 kits and disassembled COM 201 antennas. Familiarity with high frequency (HF) radios and tactical satellite

radios must also be obtained. Although these radios are available inside current formations, Soldiers at the

individual level must be trained and comfortable with tactical satellite and HF equipment, a skill most

formations currently lack outside the radiotelephone operator

For the staff and company-level leaders, units conducting infiltrations must become comfortable planning with

enablers external to the battalion. Infiltrations must be coordinated with reconnaissance elements, which may

help identify infiltration lanes, pass an infantry unit through their lines, and operate forward in the vicinity

of an infantry battalion during an infiltration. Operations like a reconnaissance handover, passage of lines,

and adjacent unit boundaries require coordinated planning and shared understanding between the two units.

Additionally, fires planning is a huge part of an infiltration. Passing targets, no fire areas, and

understanding targeting guidance are key for both the forward unit and the higher headquarters providing

artillery assets. Along with fires, coordinating with air assets, either for insertion or for resupply, takes

time and understanding. Air resupply for units forward can be a huge advantage but requires a staff that

successfully coordinates with the aviation element and conducts detailed rehearsals prior to execution.

Lastly, dismounted resupply is not something that should be overlooked; it takes planning and rehearsal to be

successful. At the company level, understanding who will move back to a company logistical resupply point,

cache, or helicopter landing zone is not a glorious task, but this is unbelievably essential to keep a unit

forward. The advantage of light infantry is lost if a unit cannot conduct operations forward of the FLOT, and

the only way to ensure this happens is through a complete logistics plan. During CTC rotations, units often

struggle with resupplying units during normal operations let alone when they have a unit far forward and not

accessible by road.

Conclusion: The U.S. Army Must Improve at Infiltration Tactics

The lesson taken from the war in Ukraine should not be that the U.S. Army must accomplish infiltrations to

counter armor advances the way Ukrainians have with the Russians. It is that infantry forces need this skill to

have success against our near-peer adversaries. Infiltrations are not trained often enough at home station, and

even when they are trained at a CTC, it is only when a unit commander makes a concerted effort to conduct one.

These operations are hard to train, conduct, and plan. However, the benefit of utilizing light infantry to their

fullest capability is undoubtedly worth the pain of hard training.

Infiltrations should be added to light infantry missionessential tasks lists (METLs). A METL task drives

everything that a unit should train to be proficient on from the team through battalion level. This will ensure

that difficult tasks associated with infiltrations are learned and practiced during a unit’s training phase.

Additionally, CTCs will ensure that units are evaluated on infiltrations against a thinking and independent

opposing force.

In the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, Ukrainian units have conducted multiple successful small unit infiltrations

across the depth of the battlefield and generated both tangible and intangible effects against a larger enemy

force. This has enabled a significantly smaller force to defend, attack, and sustain large-scale combat

operations (LSCO) for more than two years while incurring only a fraction of comparable losses in personnel and

equipment. The U.S. Army cannot choose to ignore a skill set and operational knowledge that has paid dividends

in Ukraine and in a way not so dissimilar to the lessons derived from the Yom Kippur War that was foundational

to AirLand Battle doctrine. Now is the time to begin our next study of a battle-tested skill set foundational to

LSCO — the infiltration.

Notes

Author

LTC Aaron Childers, an Infantry officer, is currently the G-3 for the 10th Mountain

Division. He previously commanded the 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th

Mountain Division, Fort Johnson, LA. His previous assignments include serving with the 82nd Airborne

Division, 1st Cavalry Division, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), the Joint Staff, and the Army Staff.

He is also a member of the Military Writers Guild.

MAJ Michael Stewart, an infantry officer, is currently the brigade S-3 for 3rd Brigade,

10th Mountain Division. He previously served as the operations officer for 2-30 IN. His other assignments

include serving with the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, 3rd Security Force Assistance

Brigade, and Army Futures Command.