Building Maneuver Live Fires for Company-Grade Officers

What I Learned From My Time in the Ranger Regiment

By CPT Patrick Kneram

Article published on: March 20, in the Spring 2025 Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time: < 11 mins

A Ranger with the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment pulls security during movement to contact as part of a live-fire exercise at Fort Johnson, LA, on 1 December 2023. (Photo by MAJ Justin Wright)

“Our training must take into consideration that the enemy will fight back, that he is attempting to kill us while we are going through our own motions. We must not fall into this trap; we must understand the fundamentals of combat and train flexibility.”

— Regimental Command Sergeant Major (Retired) Michael T. Hall,

“Fundamentals of Combat (And How to Train for It)”

Introduction: A Lesson from Ukraine

Shortly after the conflict in Ukraine began, a video surfaced on Twitter of Russian infantrymen attempting to cross a courtyard between two buildings. Unbeknownst to them, the Ukrainians had placed an armored vehicle overwatching the courtyard approximately 200 meters away. With no discernible security or overwatch of their own, the Russians took multiple casualties in the courtyard. Still without returning fire, another squad attempted to pull their fallen comrades to cover, taking further casualties. The video ends, reminding us that failure to enforce tactical fundamentals and train for realism can result in devastating losses.

The conflict in Ukraine has provided us many lessons on modern warfare to include the integration of technology and increasing imperative for survivability. However, many of these lessons come with stark reminders of the severe losses both sides suffer due to gaps in training and a lack of adherence to tactical fundamentals. As live-fire progressions remain our most effective training ground for combat, they must evolve to incorporate technology and innovation while reinforcing the foundational tactics and Soldier disciplines that are critical for success on the battlefield.

The Fundamentals of Combat

Like many units in the Army, the 75th Ranger Regiment focuses on its “Big 5” fundamentals: marksmanship, small unit tactics, casualty care, mobility, and physical fitness. Since the inception of the modern Ranger Regiment in the 1970s, these fundamentals have been the hallmark of battlefield success and saved countless Ranger lives. To enforce those principles, the 3rd Ranger Battalion designs its live-fire exercises (LFXs) to provide meaningful, repetition-based training grounded in the fundamentals of warfighting while mitigating risk through adherence to doctrine, regulations, and policy.

A Ranger assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, GA, prepares to launch a first-person view drone on 15 October 2024. (Photo by SGT Paul Won)

As combat experience diminishes across our formations, we have deliberately shifted toward a greater reliance on doctrine. This shift includes codifying our tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) into our Ranger training circulars. This renewed emphasis on warfighting fundamentals and doctrine is evident in the way we design and execute our maneuver LFXs, ensuring they remain grounded in proven principles while adapting to an evolving battlefield.

Designing Realistic Live Fires

A well-designed LFX provides multiple options for tactical decision-making, such as flanking from either direction, establishing support-by-fire (SBF) positions at various locations, including intermediate positions, and employing different breaching methods. Selecting the right range and collaborating with range control to create larger or more adaptable maneuver boxes is essential for fostering this tactical flexibility. Without these options, executing units may start planning around range constraints instead of focusing on defeating the enemy. Maintaining an enemy-focused mindset throughout all training is critical to developing adaptable, combat-ready units.

Rangers execute a “no-look” blank or ultimate training munition (UTM) iteration prior to executing live-fire iterations. This allows units to conduct maneuver as close to their tactical plan as possible. The training officer-in-charge (OIC) and NCO-in-charge (NCOIC) then lead the safety walkthrough to ensure all Rangers understand their surface danger zones (SDZs) and range limitations. We account for safety and prevent deviation from range limits through concept backbriefs to the command team and observer/ controllers (O/Cs). We also find ways to add complexity for the squad- and platoon-level leadership by adding elements of modern conflict like enemy electronic warfare (EW) and jamming, and the employment of unmanned aerial systems (UAS), counter-UAS, and loitering munitions.

Further methods we use to add realism include camouflaging targets to stress target identification, including sensitive site exploitation material tied to the scenario, and eliminating or minimizing any administration requirements from the training site. Finally, the 75th Ranger Regiment maintains an annual deviation through the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) commanding general allowing maneuver up to 15 degrees from shoulder-fired semi-automatic weapons and automatic weapons on tripod or bipod. This added realism is only acceptable due to the frequency, quality, and intensity of the marksmanship training Rangers sustain. Ultimately, SDZs are the same in training as they are in combat. Every Soldier and leader should know the SDZs of the weapons systems in their elements and be able to apply those to provide the best suppression possible for the maneuvering element.

Measuring Training Effectiveness: Assessing Ourselves

To provide better feedback and improve training outcomes, we take deliberate steps to remove some of the subjectivity from LFXs. Gone are the days of a quick leader huddle following a tough iteration, with a few “sustains” and “improves” that are typically lost on an exhausted audience. For instance, target hit counts can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of marksmanship and suppression, while timing critical portions of the operation can measure coordination and tempo. A SBF position should be judged not by how it sounds but by the tangible effects it produces on the battlefield. By grounding our assessments in measurable outcomes, we can deliver feedback that drives meaningful improvement and sharpen combat readiness.

Across the 75th Ranger Regiment, our guidance is that the traditional model of one-day live/one-night live iteration is plainly not enough. The goal of every exercise is to maximize the amount of training our units can get out of an event by “trimming the fat” around rehabilitation time, being deliberate with how we conduct our after-action reviews (AARs) and closely managing our execution timelines. This allows us to maximize the number of repetitions that Rangers get. We also save iteration time by starting the exercise from a platoon’s last covered-and-concealed position, saving tactical movements for other exercises. Importantly, we garner support from our most-experienced NCOs from across the Regiment to serve as O/Cs to invest into coaching and mentoring at every echelon.

So, what separates a good live-fire execution from a great one? Often, it comes down to the ability and discipline of the platoon’s newest Rangers. The difference lies in the details: Does the machine-gun team hit their targets on the first burst or the second? Does the Gustaf team achieve the desired effect with precision? Can a squad automatic weapon (SAW) gunner reliably fix malfunctions, both day and night? Are Rangers waiting passively for orders, or do they fully understand their purpose and proactively prepare for the next phase of the operation? Great Ranger platoons don’t leave these skills to chance — they build on the fundamentals early and often. By the time they show up for maneuver LFXs, every member of the team is ready to execute with confidence and precision, ensuring the entire platoon operates at the highest standard.

Planning for Success: The Live-Fire Glide Path

Guided by the Eight-Step Training Model, Training Circular (TC) 3-20.0, Integrated Weapons Training Strategy, and Department of the Army (DA) Pamphlet (PAM) 350-38, Standards in Weapons Training, 3rd Ranger Battalion executes its planning glide path in the following order:

- Receive command guidance on tasks to train.

- Review previous AARs and solicit feedback from senior NCOs across the battalion.

- Conduct the macro analysis including location, available ranges, and coordination with the installation live fire coordinators.

- Review SDZ and safety requirements for the range, installation, and participating organizations.

- Define the resourcing requirement to meet training objectives (weapon systems, non-organic assets, Department of Defense identification codes [DODICs]).

- Execute site reconnaissance as necessary and continually throughout the process.

- Determine the detailed ground scheme of maneuver, allowing for multiple flanking directions and positions of supporting elements, and breaching style/locations.

- Determine the construction requirements and supporting units available.

- Develop target placement and maneuver boxes.

- Validate the plan in accordance with Ranger Regiment Commander’s Policy Letter 7 (Live-Fire Policy).

U.S. Army Rangers with the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment conduct platoon live-fire exercises at Fort Benning, GA, on 14 October 2024. (Photo by SPC Samuel Dreher)

Case Study: 3rd Ranger Battalion’s Platoon Live Fire

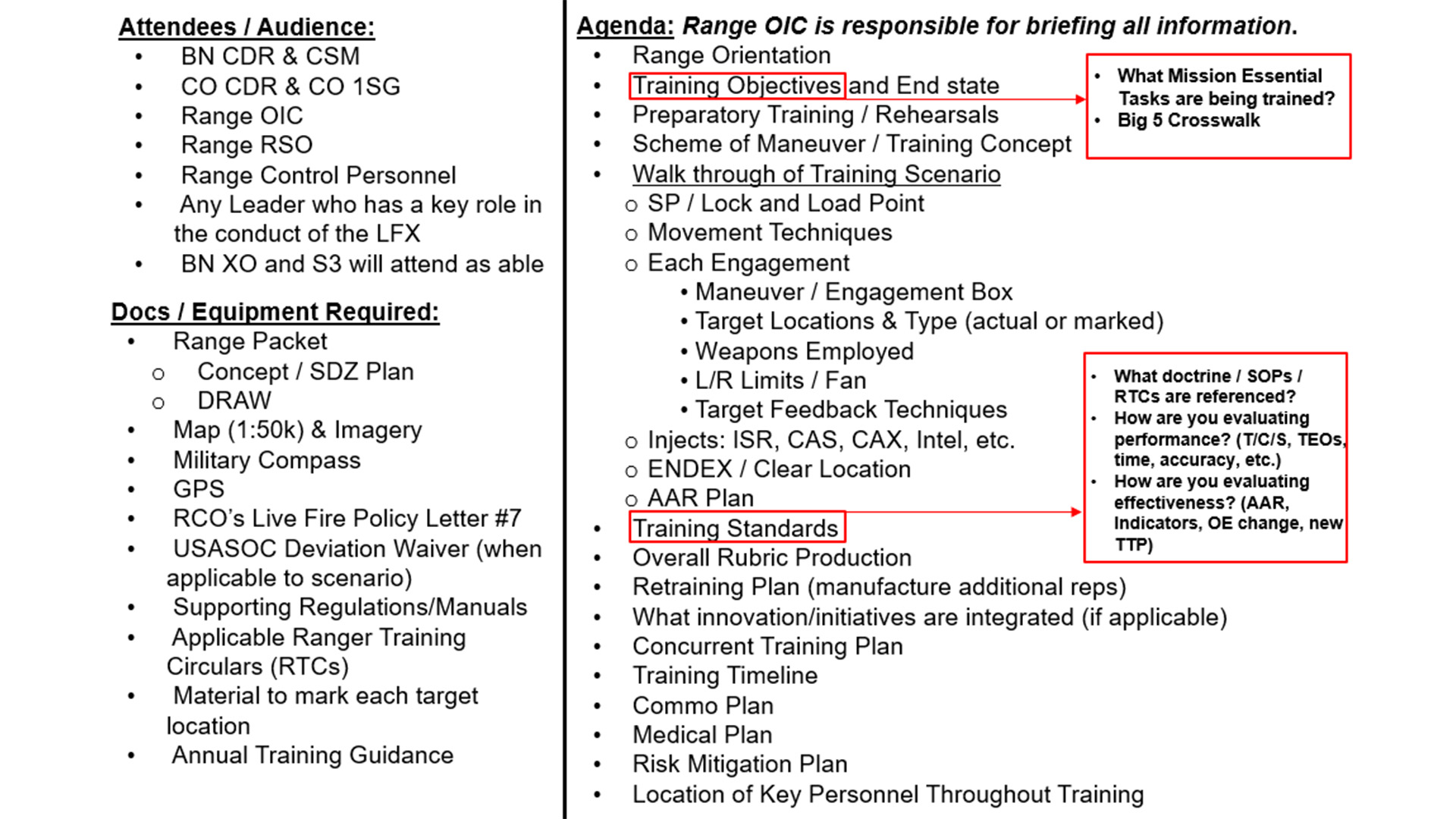

The 3rd Ranger Battalion uses and enforces an established live-fire range walk standard operating procedure (SOP) that allows the battalion commander, or his designated representative, to validate each LFX, ensuring the training is realistic, safe, and focused on battalion and regimental priorities (see Figure 1). This is in addition to Commander’s Policy Letter 7, which outlines safety requirements for weapon qualifications, range certification, validation, and execution, as well as highlights our annual deviations to DA PAM 385-63, Range Safety.

Figure 1 — 3rd Ranger Battalion Range Walk Standard for Live-Fire Exercises

Besides the design of the live fire, we drive risk mitigation and safety through our live-fire training glide path, including how we certify our executing units, planners, and the range itself. Risk management is controlling risk arising from operational factors and making decisions that balance risk cost with mission benefits. We identify risks throughout the design process by conducting a detailed analysis to identify potential hazards then implement control measures to mitigate these risks to acceptable levels. Another way to manage risk inherent to an LFX is through deliberate enforcement of a live-fire progression. Prior to executing a platoon live fire, we validate the training audience through shoot-house live fires, squad live fires, fire support coordination exercises, marksmanship qualifications, and assault breacher courses. No Ranger enters a live fire without having trained and rehearsed a task in a more limited environment.

The 3rd Ranger Battalion’s most recent platoon live fire included an explosive breach of a mined wire obstacle, knocking out a bunker, breaching a chain link fence, and entering and clearing multiple buildings. In addition to organic weapon systems, the platoon synchronized snipers; reconnaissance and first-person view (FPV) drones; fixed-wing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); an AC-130; artillery from the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault); and mortars. These training objectives and required enablers came from reviewing past AARs, the commander’s guidance in the annual training guidance, and feedback from our senior NCOs. Building a live-fire range that maximized flexibility for the assault force and synchronization of those assets required significant planning and adherence to our doctrine, regulations, and policies.

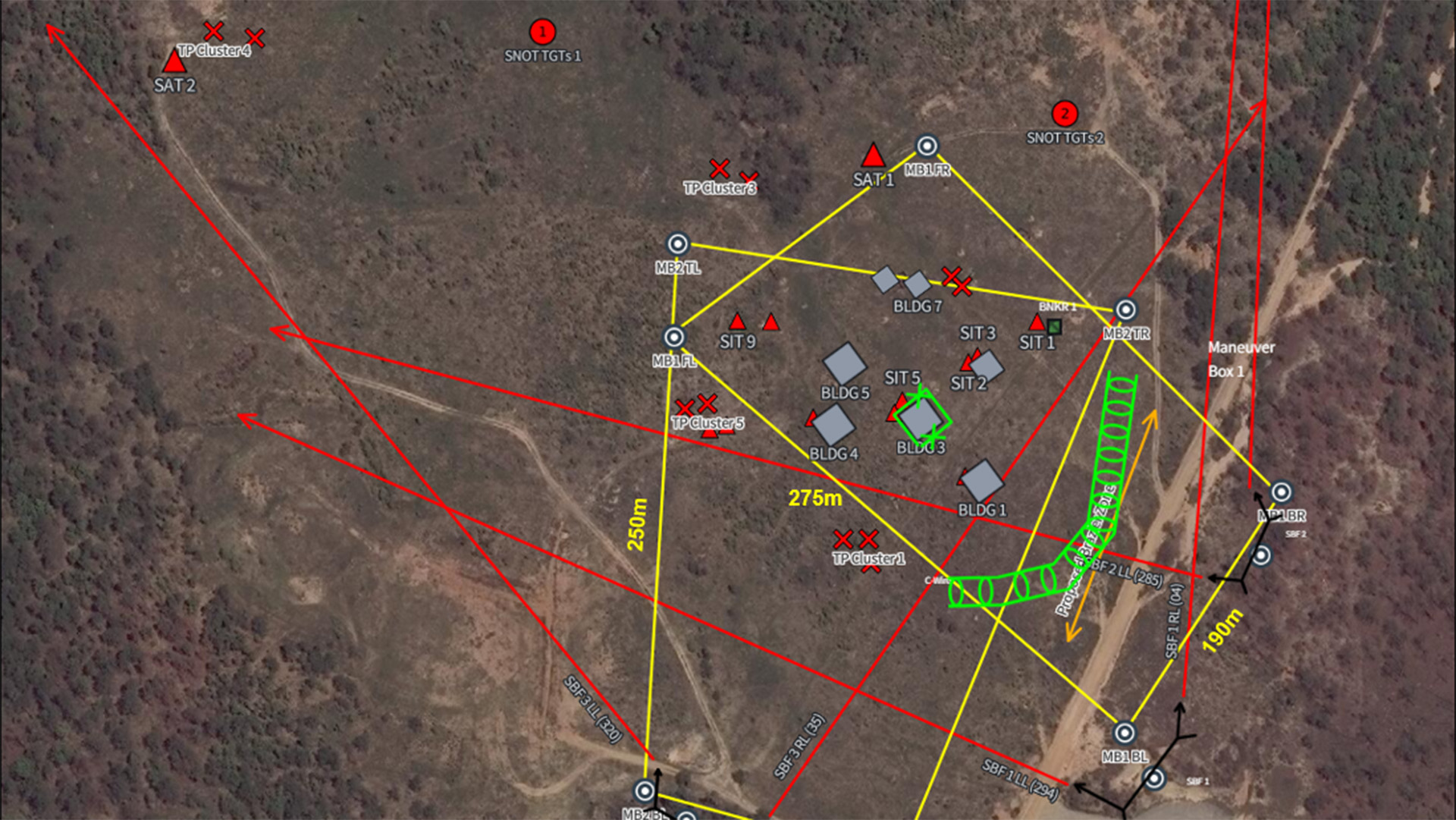

Planning for this live fire, in conjunction with our joint forcible entry exercise, began eight months in advance by finding installations and ranges that met our training objectives. While many had great options to meet those objectives, our most feasible course of action landed us back at Fort Benning, GA. To provide the most latitude for integration of close air support and indirect fires, we chose a piece of land abutted to the northern impact area. While great for non-organic assets, this land required significant engineering and development to create a challenging live fire. For instance, we needed to resource engineers to build a series of wooden buildings, complete target pits, and build a bunker safe for live grenades. This also meant we would need to integrate “hot walls” into our risk mitigation methods. A hot wall is a designated wall within a structure for the placement of targets that keeps direct fires within the range limits while also keeping the targets away from areas that friendly troops may maneuver or place supporting elements. This target placement is validated multiple times by planners, our internal safety team, and leadership across the battalion. The design of the maneuver boxes also allowed the platoons to establish SBF positions in different locations and assault from multiple directions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 — Depiction of Multiple Maneuver Boxes and Support-by-Fire Options for the Assault Force

Conclusion: Preparing for Modern Combat

As history shows, the nature of the next conflict is unpredictable. While the environment, enemy capabilities, or even the ways of war may evolve, small units applying the fundamentals of combat will remain the decisive element. By prioritizing rigorous, realistic live-fire training and qualty repetition, we ensure our Rangers are ready to face tomorrow’s battles with confidence and competence. This approach will ensure that when the nation calls and the spear is thrown, it is small elements of lethal Soldiers, grounded in the fundamentals of combat, who arrive on the front, sharp edge of that spear.

While the environment, enemy capabilities, or even the ways of war may evolve, small units applying the fundamentals of combat will remain the decisive element. By prioritizing rigorous, realistic live-fire training and quality repetition, we ensure our Rangers are ready to face tomorrow’s battles with confidence and competence.

Author

CPT Patrick Kneram currently serves as the commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. He has served in a variety of staff and command positions across both conventional and special operations units, including serving as the lead planner for multiple live-fire exercises