The Battle of Fort Ridgely: Artillery Saves the Fort, and Minnesota, for the Union in August 1862

Part 4: Final Dakota Assault on Ft. Ridgely, 22 AUG 1862

Field Historian’s Corner

By Dr. John Grenier, Field Artillery Branch Historian

Article published on: March 1, 2024 in Field Artillery 2024 Issue 1

Read Time: < 9 mins

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21236/AD1307136

This is the final part of the FAPB four-part series on the Battle of Fort Ridgely. We used the preceding edition (see Part 3 in issue 6-23-3) to explain the Dakotas’ first attacks on Ft. Ridgely on 20 AUG 1862, and we focused on the heroics of the fort’s defenders, led by field artillerymen, in repulsing the Dakota’s attack. This part tells the story of the Dakota’s final, desperate, and in the end, failed assault on Ft. Ridgely on 22 AUG 1862. It explains points to ways that Redlegs might want to consider the events that transpired at Ft. Ridgley, ways that have deep significance for both American history and the history of the Branch.

After the failed, initial assault on Ft. Ridgely on 20 AUG 1862, Little Crow spent the next day lobbying and cajoling at the Lower Agency while other Dakotas spread the net of rape, pillage, and murder over the farmsteads that escaped their attention the previous three days. Little Crow abandoned trying to explain grand strategy, and he instead promised that Ft. Ridgely’s commissary and contractor huts remained full of booty and cash. Upwards of 800 warriors—many of them from the Wahpeton and Sisseton bands who to this point had sat out the fighting—agreed to join him on what he promised would be the last and decisive attack on the fort.

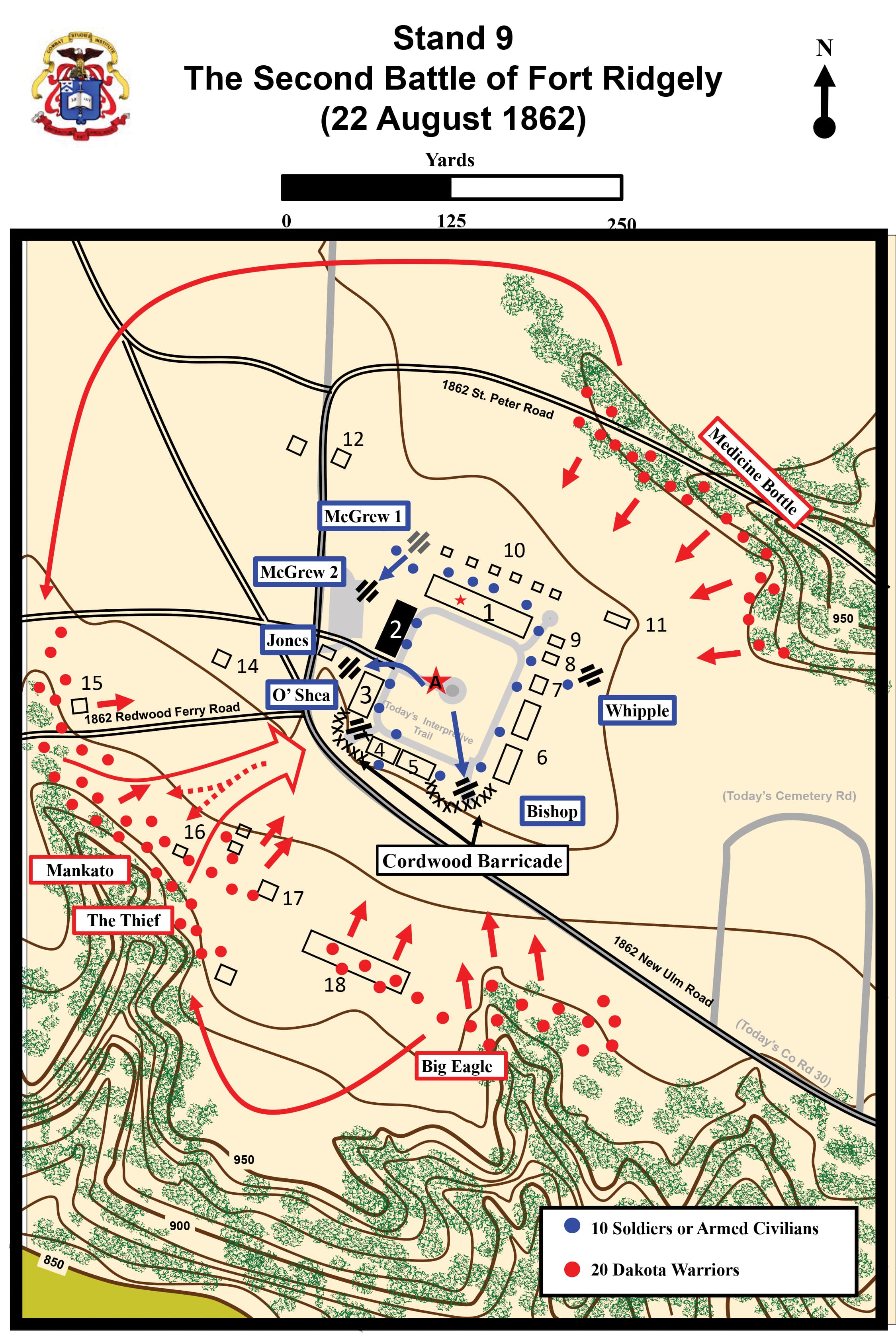

Little Crow’s plan was simple. He intended to encircle the fort, and upon his signal, Dakotas could rush its defenses on all sides. Medicine Bottle would again attack from the northeast. Mankato volunteered to lead the warriors to overwhelm the Soldiers who crewed the gun at southwest corner. The Thief and his followers, convinced the hardest fighting and therefore best opportunity to win glory might take place at the southwest corner, joined Mankato. Big Eagle intended to attack from the south and southeast. Little Crow told the Dakotas that many of them might die at Ft. Ridgely, but the Blue Coats could not keep up fires to repel all of them if they attacked in unison as he directed. Little Crow instructed that the Dakotas must at all costs focus single-mindedly on the artillerists. He promised to personally and publicly give each warrior who killed a soldier at the cannons an eagle’s tail feather that he could wear in his headband for the rest of his life, and he assured the warriors that he intended to be with them in the thick of the fighting. Once the Dakotas captured the big guns, they could make short work of the Soldiers and then, as far as Little Crow cared, plunder the fort’s stores and refugees to their hearts’ content.

Dakota attacks on Ft. Ridgely on 22 AUG 1862.

SGT John Jones suspected that the Dakotas learned their lesson on 20 AUG, and the next time they appeared outside the fort, they intended to rush it en masse and focus a thrust somewhere along the south side. He therefore remained at the southwest corner. SGT James McGrew took up station with his 12-pound cannon at the northwest corner of the parade field, and Mr. John Whipple with his similarly sized howitzer, returned to the northeast corner. Luckily for the defenders, it rained most of the night and drenched the fires that had obscured their views beyond the barricades. Instead of fighting building fires, the Soldiers piled cordwood into four-feet high barricades at southwest and southeast corners. While the defensive positions and scheme of fires were better developed than they had been during the attack on 20 AUG, and more Soldiers were prepared to operate the guns, no one inside the fort had seen signs of more relief headed their way.

The assault of 22 AUG took time to develop. Several Dakotas, camouflaged with prairie grass and flowers that made them difficult to see until they presented themselves, crawled forward and sniped at defenders late in the morning. Others moved into the stables and sutler’s house on the south side of the fort. Well-placed artillery shells set those buildings on fire, and they drove the Dakotas from them. Medicine Bottle appeared as if he intended to charge from the northeast corner, but several rounds from Whipple’s howitzer quickly put an end to that. Medicine Bottle left a handful of men in the wood line, and he shifted most of his warriors the long way around to the west of the fort, to join the warriors on its south side. The defenders saw this movement unfold, though they were not unsure what the Dakotas intended. SGT McGrew wheeled the reserve 24-pound field piece from the center of the parade field to just south of the commissary, while his 12-pound mountain howitzer’s crew also repositioned the piece to face the south. SGT John Bishop moved another reserve mountain howitzer from the southeast and faced it to the southwest. The artillerists loaded all the cannons with double charges of cannister.

Around 4 p.m., the Renville Rangers heard a loud voice shouting in Dakota. They assumed it was Little Crow, though it most likely was Mankato, because the former had been carried off the battlefield after shrapnel from Whipple’s gun hit him in the head and knocked him senseless earlier in the day. One of the métis ran to SGT Jones and reported that the rangers believed the Dakotas were marshaling at the southwest, just as hundreds of warriors swarmed out the ravine. Mr. Dennis O’Shea adjusted the elevation and the direction on the 6-pound field gun that he commanded, and the Renville Rangers laid down fire from their rifles. Dozens of Dakotas gained the barricade and the rangers fell back before O’Shea fired the field gun into the mass of Indians. A split second later, McCrew, with the 24-pounder, and Bishop followed suit. Joseph Coursollo, a métis from the Redwood Agency who fought as a volunteer citizen, recalled, “At the instant the Indians joined forces, all three cannon roared. The shells tore great holes in the ranks of the warriors … The Indians skedaddled and the fighting was over.”

Both sides agreed that the artillery saved the day for the Blue Coats on 22 AUG, just as it had two days earlier. LT Timothy Sheehan, in his official after-action report, explained, “The Indians prepared to storm, but the gallant conduct of the men at the guns paralyzed them, and compelled them to withdraw, after one of the most determined attacks ever made by Indians on a military post.” Big Eagle, in his 1894 memoirs “A Sioux Story of the War,” wrote, “But for the cannon I think we would have taken the fort … the cannons disturbed us greatly.”

After tasting defeat at second time at Ft. Ridgely, the Dakotas abandoned all hope of taking it, and they again focused on New Ulm. Although the settlers fled from the town after repulsing the second (and more ferocious) attack on 23 AUG, few doubted that at Ft. Ridgely the Dakotas already had lost the war. Union forces from Ft. Snelling flowed into Southwest Minnesota over the next several days. While COL Henry Sibley proved frustratingly slow (at least from the settlers’ perspective) in moving beyond Ft. Ridgely, ground truth was that Dakotas could not stop the Army from operating at will across all of Southwest Minnesota. The Army’s mountain howitzers, in particular, gave Union Soldiers, state militia, and Renville’s Rangers a tremendous advantage over the Dakotas, and allowed them to quash uprising in its remaining battles, at Birch Coulee and Wood Lake, in large measure by killing the Dakotas’ leaders. Mankato, for example, was killed by a cannon ball at the Battle of Wood Lake. On 23 SEP, the soldiers’ lodge gave up over 250 prisoners to COL Sibley at Camp Release. Nearly 2,000 Dakotas surrendered to Federal and state authorities, though Little Crow fled on to the Northern Plains, and Medicine Bottle and Little Six sought refuge from the British government in Canada. The Army arrested 392 warriors, and it confined hundreds of Dakota men, women, and children in an internment camp on an island in the middle of the Minnesota River outside Ft. Snelling. A commission composed of officers of the Minnesota Volunteer Infantry sought to hold accountable the perpetrators of the uprising, and in less than six weeks’ time, it tried and sentenced 303 Dakota men to death for rape and/or murder. President Abraham Lincoln, America’s greatest president, and a lawyer by training and someone almost obsessively focused on finding justice and reconciliation, even in the midst of a civil war that was tearing apart the nation , personally reviewed each conviction. He approved death sentences for 39 Dakotas. Several warriors who could prove that they fought only at Ft. Ridgely saw their sentences commuted since they were, in today’s terms, legal combatants. Big Eagle was among them. On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men—including some who protected white and métis captives—were hanged in Mankato in the largest mass execution in American history. Congress abolished the Dakota agencies and declared the 1853 treaty null and void. In May 1863, Minnesota banished the survivors (hundreds died over the course of the winter) of the internment camp to present-day South Dakota. Two settlers killed Little Crow in July 1863 outside Hutchinson, Minnesota; the legislature paid $500 for his scalp and displayed it in the state’s history museum for decades. The British turned Medicine Bottle and Little Six over to US authorities in 1864. The Army hanged them at Ft. Snelling, in November 1865; medical students used the corpses as cadavers.

Determining the legacy of the Dakota Uprising is a task fraught with pitfalls. The Battle of Ft. Ridgely might seem an insensitive choice for study, one that glorifies victory against a foe that likely never had a chance of winning and minimizes the Army’s substantial role in the hardships inflicted on indigenous peoples during the conquest of the American West. But nuance is often elusive in history. In 2012, Minnesota’s governor Mark Dayton called for 17 AUG to be a “Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation” in his state. Emotions over the Dakota Uprising continue to run raw a decade later, and they burst to the surface each 26 DEC when the Dakotas publicly remember and mourn the executions at Mankato.

Beginning in 2005, members of the Sioux Nation rode to Mankato during the Christmas season to publicly remember and honor the Dakotas executed there on the day after Christmas, 1862. The year 2022 marked the last of the Remembrance Rides.

The history of the Battle of Ft. Ridgely therefore should not, and cannot, be plucked from the larger currents of American history and studied in isolation, no matter how self-contained, or unpleasant on a macro level, it seems. Nor should FA professionals ignore the first instance in Army history in which artillerists defended their outpost until the relief arrived and saved it. In the final analysis, we should remember Big Eagle’s words: “We went down determined to take the fort, for we knew it was of the greatest importance to us to have it. If we could take it we would soon have the whole Minnesota valley.” One can only imagine how much more settler, métis, and Indian blood might have flowed if the Dakotas had indeed taken Ft. Ridgely and the entire Minnesota River Valley in August 1862 and forced the US Army to fight to regain it.

Endnotes

1. The Métis (meti(s)/ may-TEE(S) are an Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada’s three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, Northwest Ontario and the northern United States. They have a shared history and culture, deriving from specific mixed European (primarily French, Scottish, and English) and Indigenous ancestry, which became distinct through ethnogenesis by the mid-18th century, during the early years of the North American fur trade.

Author

Dr. John Grenier is the FA Branch/USAFAS historian at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.