Lieutenant Development

By First Sergeant Daniel Ansong

Article published on: January 1, 2024 in the Engineer 2024 Annual Issue

Read Time: < 7 mins

Beginning with the first publication of leadership doctrine in 1948, the Army had always described leadership as a process; it was defined as “the process of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization.”1 This is important because a process can be learned, monitored, improved, and repeated. However, the latest version of Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession, published in July 2019, describes leadership as an activity; it states that leadership is “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization.”2 Why the change? To many, the two definitions may be tantamount—but are they?

According to the Oxford Learners Dictionary, an activity is something that is done for interest or pleasure or to achieve a particular goal, while a process is a series of steps completed to achieve a particular result.3 An activity involves acting on something that is already known; it does not require guidance or deliberate supervision. Walking, running, and fishing are examples of various daily activities. But leading a group of highly trained individuals qualifies as something more than a mere activity. Leadership requires many skills and encompasses complex and dynamic relationships between leaders, subordinates, and seniors who depend on each other to attain a mutually desired goal. It takes time to develop good leadership

How would a 10-year-old child who inherits a Fortune 500 company know what to do with the new asset? How could that child be empowered to manage the resulting wealth and prestige? A strategic process would be required. Unfortunately, the life of a young engineer officer is similar to the situation of the child beneficiary. Upon completion of the 19-week-long Engineer Basic Officer Leader Course, a young lieutenant may be assigned to a horizontal construction platoon but deployed to conduct sapper tasks or appointed as a task force engineer to advise a maneuver commander on engineer capabilities for an incredibly challenging task. The engineer, who still needs to gain experience, may be placed in charge of personnel and equipment and simply directed to “figure it out.” Who is going to assure the young engineer lieutenant that things will be okay when he or she has issues at home but must still show up to motivate subordinates every day?

While serving as an Engineer Basic Officer Leader Course platoon trainer, I was grading an operations order (one of the critical course events) when a very disciplined and intelligent student began his operations order briefing. A few seconds into the briefing, the student started repeating himself. He became acutely uneasy and apprehensive. I immediately realized that something was wrong. I excused myself and conferred with my officer counterpart, who was also grading an operations order in another bay. I quietly asked if he was aware of the student’s situation, and I learned that the student had previously been on the phone all night long, talking to his Family and his lawyer about a custody battle with his former wife. With this troubling news, I returned to my bay and continued grading. During our after-action review, I expressed my sincere sympathy regarding the student’s plight and encouraged him to be strong. I acknowledged how challenging it can be to be a leader in today’s Army and reminded him of the need to separate his personal life from his professional life. Given their lack of experience and the complexity of what young officers are asked to do, the development of these lieutenants is in everyone’s best interest

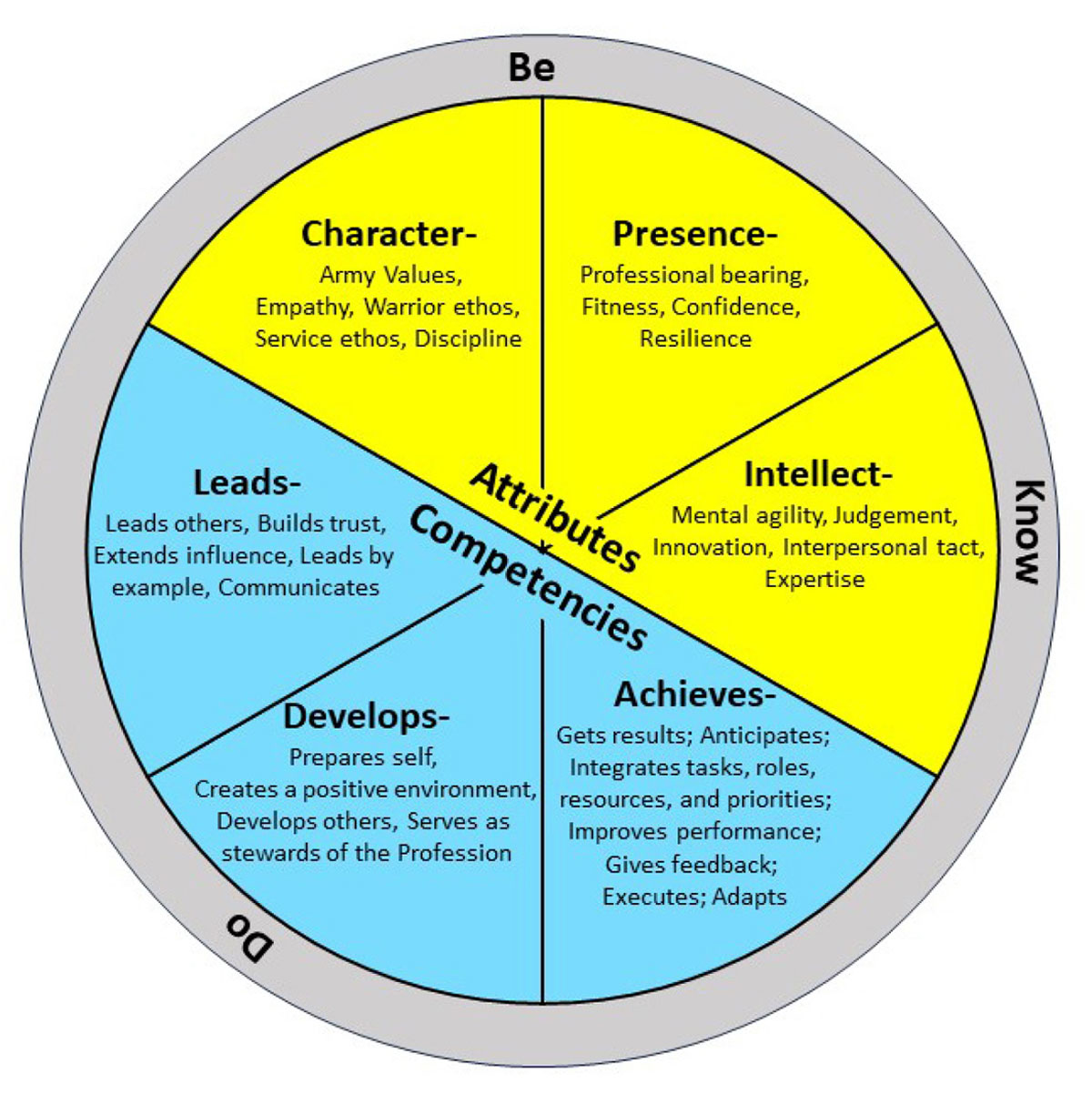

Leader development constitutes stewardship of the profession, which is critical as we strive to achieve the Army mission and vision. Leaders at all levels must make developing and providing quality mentorship to their lieutenants their utmost priority. This can be accomplished through use of the Army Leadership Requirements Model, which is outlined in ADP 6-22. According to ADP 6-22, an Army leader is “anyone who, by virtue of assumed role or assigned responsibility, inspires and influences people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization.”4 Army leaders motivate people within and outside the chain of command to focus thinking, shape decisions, and pursue actions for the greater good of the organization. This is difficult and time-consuming; it cannot happen overnight.

The Army Leadership Requirements Model is grounded in historical experience and determinations about what works best for the Army, and Army research supports the completeness and validity of the model. The model identifies core competencies and attributes applicable to all echelons and types of Army organizations and conveys expectations and establishes required capabilities of all Army leaders, regardless of rank, grade, or position. The Army Leadership Requirements Model significantly contributes to individual and unit readiness and effectiveness. The components of the model are centered on what a leader is and what a leader does, as shown in Figure 1. Leaders’ core attributes of character, presence, and intellect enable them to apply core competencies to enhance their proficiency. Leaders who gain expertise through institutional learning, operational assignments, and self-development tend to be versatile enough to adapt to most situations and to grow toward greater responsibilities.

The difference in the competence and confidence of a platoon sergeant and a newly commissioned lieutenant is experience. Although mentorship is voluntary, new lieutenants need all the mentorship they can get and leaders should incorporate mentorship programs into the daily battle rhythm of their organizations. While assigned to the 20th Engineer Battalion, 36th Engineer Brigade, Fort Cavazos, Texas, we conducted various leader professional development activities, including a 5-day field exercise for organizational leaders (platoon leaders and their platoon sergeants). Training on leadership topics ranged from engagement area development to patrol base operations and the military decision-making process. The 20th Engineer Battalion has a great senior leader mentorship program.

From my experience, I estimate that the average age of lieutenants graduating from the Engineer Basic Officer Leader Course is about 24. But successful graduation does not mean that the young officers are ready to accomplish every mission. It takes years of mentorship, development, and experience to separate the chaos at home from the professional responsibilities of a leader. Organizational-level leaders fulfill the stewardship function of the Army profession by placing a high priority on investment in the development of future leaders at all levels, as competent leaders are a crucial source of combat power. With conditions set for a robust leader development system in which organizational members learn from their experiences and those of others, organizational leaders can take advantage of numerous avenues of approach for strengthening lifelong learning, such as—

- Virtual training and learning centers

- Simulations

- Assignment-oriented training

Conclusion

The leadership at echelon is responsible for the U.S. Army’s asymmetric advantage in this volatile and complex world. Leaders are made, not born—and the development of good leaders requires a significant investment of time and energy. Leader development is a deliberate, progressive, continuous process that involves the career-long synthesis of training, education, and experiences acquired through opportunities in the institutional, operational, and selfdevelopment domains. Because leadership is rooted in Army values, Army leaders are competent, committed professionals of character. Senior leaders must continue to hold subordinate leaders accountable by establishing left and right limits while implementing the Army Leadership Requirements Model, which clearly articulates the need for leader competency.

The development of leaders is a crucial component of our profession of arms. Leadership is a process that can be completed through deliberate leader development and mentorship.

Figure 1. Army Leadership Requirements Model core attributes and competencies

Endnotes

Author

First Sergeant Daniel Ansong is a platoon trainer for the 554th Engineer Battalion, 1st Engineer Brigade, Maneuver Support Center of Excellence, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. He holds an associate’s degree in civil engineering technology from Accra Technical University, Ghana, West Africa. He is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in human resource management from the American Military University.