Sources and Limitations of Command Authority over the Army Reserve Component

By Major Amanda M. Baylor

Article published on: January 1, 2024 in the Army Lawyer issue 2 2024 Edition

Read Time:

< 27 mins

MAJ Amanda B. Baylor, USAR SVC Deputy Program Manager, briefs attendees at the active/Reserve

component integrated SVC Regional Training held 5-7 December 2023 at the USARLC in Gaithersburg, MD. In this

photo, MAJ Baylor specifically addresses active component SVCs and paralegals about the uniqueness of the USAR

(especially part-time support) within the context of the SVC Program. (Credit: 1LT Amber Lamb, USARLC)

The joint force staff judge advocate (SJA) has a pivotal role in assisting the operational planners to

anticipate, understand, and pursue necessary authorities. Joint force commanders rely heavily on their legal

advisors for accurate, timely advice concerning authorities and limits that impact planning and execution.

Their recommendations also help shape the commander’s guidance and intent.1

The total U.S. Army is organized into the Regular Army and Reserve component, which is comprised of the Army

National Guard of the United States (ARNG) and the U.S. Army Reserve (Reserve).2 Across all components, the Army chain of command

consists of commanders who exercise discrete authority.3 Command authority is “the authority a commander in the [Army] lawfully

exercises over subordinates by virtue of rank or assignment.”4 Command authority for the Reserve component is different from command

authority for the Regular Army. Recently, the frequency and duration of Reserve component activations have

increased exponentially;5 commanders

must address important issues unique to this operational force multiplier.

Despite the increases in frequency and duration of Reserve component activations, some commanders treat their

Reserve and ARNG Soldiers just like their Regular Army counterparts.6 Commanders must acknowledge that there are

differences between these populations both in the source of the command authority over them and in the unique

circumstances that come with leading these Soldiers effectively. Whether limiting or permissive, command

authority outlines the type of action(s) commanders may take and how they may act.7 Although commanders have broad authority to timely

meet their significant responsibilities, they must know of and operate within specific limitations on the

various mechanisms through which these powers are conferred. Operating within the bounds of command authority is

woven into the very fabric of our national defense strategy; leaders who assume command must understand and

appreciate that disregarding or misinterpreting applicable authorities can lead to injury, financial mistakes,

and even criminal proceedings.8

The proper exercise of command authority expands well beyond formal authority in law or regulation,9 where duties include both express

and inherent command and control over subordinates.10 Command and control is, therefore, the conduit through which commanders

exercise their authority and direction over Soldiers assigned and attached to their command11 and over assigned resources and equipment.12 Commanders must plan and

effectively use all available resources to complete their missions through the “employment of, organizing,

directing, coordinating, and controlling military forces” while ensuring their “health, welfare, morale, and

discipline.”13 No other military

role matches the totality of express command duties coupled with ethical and legal obligations inherent in

command.14

Because commanders cannot rely solely on express authority given through written or oral instruction, they must

know and understand what decisions and actions are within their discretion (implied authority). They must know

of any restrictions or withholdings that impact their authority to act to determine whether they should request

new or additional authority through their technical chain.15 This requires a fundamental understanding of two separate yet distinct

chains of command authority as it flows from the U.S. Constitution to the President and to Congress.

This article explains the Constitution’s grant of broad military authority to the President to serve as

“Commander in Chief”16 and to

Congress to “make rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces,”17 as well as delegated command authority from this

highest level. Through law codified in the U.S. Code, command authority flows from the President through the

Department of Defense’s (DoD) Service Secretaries, such as the Secretary of the Army (SECARMY), down to

commanders of each Service and through multiple command echelons (“theater army, corps, division, brigade,

battalion, and company”).18

Combatant commands (COCOMs) are key components of this delegation chain, as combatant commanders

(CCDRs) exercise command authority over assigned Reserve component members mobilized to Federal active duty.19

Lastly, this article explores how decentralized mission command requires commanders to exercise inherent command

authority. It highlights key differences between Reserve component and Regular Army duty statuses and identifies

sources of Reserve component20

command authority. It discusses how the ARNG operates primarily under title 32 U.S. Code authority and the

Reserve operates under title 10 U.S. Code authority. It also explains how National Guard Soldiers in a title 10

status outside the United States operate under CCDR command authority separate from a title 32 chain of command.

Finally, it addresses key differences in applicable law, subject to duty status, with which commanders should be

familiar.

This article will aid senior judge advocates (JAs) (such as staff judge advocates) in understanding important

challenges and limitations Regular Army and Reserve component commanders face while executing their command

authority. Although JAs provide commanders with legal advice on a multitude of issues unique to the Reserve

component,21 “the judgment of the

commander is paramount.”22

Accordingly, JAs must advise commanders to exercise their inherent command authority and operate among the gray

space within black-and-white authority to make timely decisions and take effective action.

BG Gerald R. Krimbill, Commanding General, U.S. Army Reserve Legal Command (USARLC), addresses

special victims’ counsel (SVCs) and SVC paralegals attending the first active/Reserve component integrated SVC

Regional Training held 5-7 December 2023 at the USARLC in Gaithersburg, MD. (Credit: 1LT Amber Lamb, USARLC)

Background

Command Authority under the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution grants

Congress legislative power “to declare War,” “raise and support Armies,” “provide and maintain a Navy,” “make

Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces,” call forth “the Militia to execute the

Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections, and repel Invasions,” and “provide for organizing, arming, and

disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United

States.”23 The Uniform Code of

Military Justice (UCMJ) and Servicemembers Civil Relief Act24 (SCRA) are primary examples of legislation Congress passed with its

constitutional powers to regulate military operations. Congress can also legislate limits on the President’s

authority to conduct military operations, creating a fluid balance of war powers between Congress and the

President.25 Thus, the line of

demarcation between the legislative and executive branches’ constitutional authority is not absolute. For

example, Congress can limit funding to control the President’s ability to carry out military operations.26

The Constitution grants the President executive power to serve as the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Army and

Navy as well as militia “when called into the actual Service of the United States.”27 It also grants executive authority to make

treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senate concurs and ratifies them.28 Congress cannot match the President’s broad

military authority where the President specifically exercises command authority over the U.S. Armed Forces.29 The President can manage the

executive branch’s operations,30

including the Army’s command authority, by issuing executive orders (EOs). This is a critical separation of

power between the executive branch and the legislative branch, as command authority requires both a “grant of

authority [(power in law)] and necessary freedom of action.”31

The President’s authority and freedom of action to pursue military operations includes “inherent or implied

power” that does not always require congressional authorization (unless a statutory bar exists).32 Executive order legal and

regulatory authorities are vested in law (such as the UCMJ, DoD directives, and Army regulations) and enhanced

through “specific powers granted under the authority of immediate commanders.”33 As such, EOs are directives that help define and

confer military command authority as a source of law that does not require congressional legislation.34

Through EOs, presidential power has expanded over time; Commanders in Chief have influenced both foreign and

domestic affairs over which the DoD has exercised significant command authority—all without asking for

congressional approval or encountering restrictions by Congress.35 Because the Constitution limits Congress’s ability to regulate or

restrict the President’s constitutional command authority, Congress should have less control over how the

President employs executive authority.36 Without this separation of powers, Congress could fundamentally hinder

the President’s ability to carry out the duties of our Nation’s Commander in Chief. This could create

unnecessary confusion over sources of command authority over the Armed Forces and cause leadership concerns to

grow.

Through its power to raise and support armies and declare war, Congress cannot enact legislation that interferes

with command authority over forces and military campaigns; that power belongs to the President.37 Absent any court rulings on

point, it is unclear whether Congress can regulate military deployments without overstepping presidential

authority.38 In March 2011,

President Obama directed U.S. Armed Forces overseas to conduct limited military operations to aid United Nation

member states in protecting civilians from attacks.39 Afterward, he reported to Congress that he had “constitutional

authority, as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive and pursuant to his foreign affairs powers” to act without

legislative authorization.40

Other Presidents have sent troops into battle without Congress’s official declaration of war.41 Such action underscores the importance of

establishing command authority on the executive side of a clear line of demarcation.42 Sometimes, this line between congressional and

presidential war power is blurred.43

Nonetheless, it remains clear, and Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court agree with the executive,

that not all presidential and congressional military authority is retained at the top.

Delegated Command Authority

Military authority within the executive

and legislative branches does not exclusively rest with the President and Congress, respectively.44 Both branches have delegated

command authority in some respect.45 Just as military powers flow from both the legislative and executive

branches, command authority originates from several sources, including law, regulation, and policy.46 By law, military functions are

vested in the President and are delegable to the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF).47 By EO, President George H.W. Bush delegated to

the SECDEF complete military authority to assign commanders.48 Consequently, most military power and authority flows from the

President, as Commander in Chief, through the SECDEF, to COCOMs and the Services, and down to subordinate

commands.49 The President and

SECDEF exercise command authority over the Army through two separate chain-of-command branches.50

Command authority flows through two chains of command among all Army components: the operational chain of command

and the administrative chain of command.51 Operational control (OPCON) of forces is the authority to “perform those

functions of command over subordinate forces involving organizing and employing commands and forces, assigning

tasks, designating objectives, and giving authoritative direction necessary to accomplish the mission.”52 Operational control for missions

flows from the President to SECDEF and down to the CCDRs who exercise COCOM authority over missions and forces

that SECDEF assigns to them.53

Specific to the Army command structure, the chain of command flows through one of three major commands (four

Army Commands, eleven Army Service Components Commands that support COCOMS, and thirteen Direct Reporting Units)

down to subordinate commanders.54

The President assigns CCDRs and approves SECDEF’s assigned missions and forces.55 Upon consulting the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

of Staff (CJCS), SECDEF further delineates CCDRs’ authority to ensure they have the requisite authority to

“exercise effective command over those commands and forces.”56 As such, command authority over COCOMs for operational missions is

extensive and includes assigning subordinate commanders their command functions.57 In these assignments, however, CCDRs’ authority

to issue orders is limited.

A COCOM’s authority is not wholly transferable; certain functions cannot be delegated, such as “giving

authoritative direction over all aspects of military operations, joint training, and logistics necessary to

accomplish the missions assigned to the command.”58 As further discussed below, this is important because when the President

mobilizes ARNG units to Federal active duty, they fall under COCOM authority (outside the title 32 ARNG command

chain) over the theatre in which they operate.59 Operational control, which can be delegated to subordinate commanders,

is an integral component of the COCOM’s authority.60 It includes the authority to perform command functions necessary to

complete assigned missions but generally does not include “matters of administration, discipline, internal

organization, or unit training,”61

otherwise known as administrative control (ADCON).62 Combatant commanders have ADCON authority to carry out their Federal

statutory (title 10, U.S. Code) responsibilities for administration and support over subordinate units.63 They can delegate ADCON

authority to subordinate commanders but should document this in writing to avoid having their CCDR command

authority usurped.64

Within COCOMs, SECDEF manages Armed Forces and military operations across seven geographic combatant commands

(GCCs) and four functional combatant commands with designated areas of responsibility.65 The Secretary of Defense directs the Service

Secretaries to assign or allocate military forces to GCCs and exercise certain command authority over their

respective units and fill different Service component command roles (such as U.S. Army Central Command).66 To prioritize their key role of

planning and oversight, COCOM headquarters delegate authority to execute OPCON and tactical control (TACON)

missions to Service component commands and subordinate commands.67 Yet, only COCOM commanders have the authority to deploy forces from

every Service.68

Much like COCOMS combine forces across the different military departments for a joint war-fighting role, the Army

combines its distinct troops among the Regular Army and Reserve component to provide a unified federalized force

to which Federal command authority equally applies.69 Just like CCDRs are responsible for total force structure integration,

Regular Army commanders must integrate the Reserve component into its ranks operationally to “help meet both

steady state peacetime engagement and contingency requirements of the [CCDRs] . . . at home and abroad.”70 Because joint operations are

generally conducted through decentralized execution,71 Regular Army commanders must understand that differences exist between

Regular Army and Reserve component command authority.

Decentralized Command Authority

After the Civil War, American

commanders began decentralizing command execution by using mission orders to achieve a desired end state.72 This developed into mission

command authority, which is a type of ad hoc authority commanders have over “the conduct of military operations

through decentralized execution based upon mission-type orders.”73 It is best described as the “creative and skillful use of authority,

instincts, intuition, and experience in decision-making and leadership to enhance operational

effectiveness.”74 Commanders use

mission command to empower subordinates to make disciplined decisions through command and control, without a

direct order, and accept the risk of interpreting commander’s intent.75

Balancing delegation of authority against manageable risk requires trust, experience, and a solid understanding

of command authorities.76 This is

critical, as commanders must always have a lawful mission (assigned duty and function) and authority.77 They must know what their unit

function and mission are and where their authority comes from. They cannot just say, for example, EO 1233378 allows intelligence collection.

They must trace their authority through orders (concept of operations, operations order, etc.).79 Commanders must further balance

express mission command with inherent command authority.80 They do this through command and control, which gives commanders broad

authority to manage all aspects of forces to accomplish the mission.81

Commanders have inherent authority to regulate good order and discipline and support the health, safety, and

morale of troops.82 For Regular

Army commanders, inherent command responsibility also includes providing “consultation and liaison with the ARNG

and USAR to ensure interaction and synchronization among [Regular Army] and USAR concerning Family assistance

and readiness issues.”83 Judge

advocates must advise commanders on express and inherent command authority, including all delegated authority,

authority withheld, and authority to exercise discretion to ensure readiness, good order, and discipline. This

will help achieve harmony across Army components, wherein some Soldiers have multiple duty statuses.

Commanders Must Be Aware of Reserve Component Roles and Duty Statuses

Reserve Component Command Authority (Title 32 versus Title 10 Status)

The Army National Guard primarily operates in a title 32, U.S. Code, duty status while the Reserve solely

performs missions while in a title 10 status—just like the Regular Army.84 The Regular Army and Army Reserve are always

under the command and control of the President.85 The Regular Army consists of full-time units ready to employ land

power,86 and it relies heavily on

the Reserve component as a total force multiplier.87 The Reserve provides half of the Army’s sustaining units and a good

portion of mobilization capability.88

The Reserve

The Army Reserve originated in the twentieth century from Congress’s

constitutional authority “to raise and support Armies.”89 Reserve component Soldiers receive the same initial basic and advanced

training as the Regular Army.90

After completing initial training, however, Reserve component Soldiers return to their civilian jobs (and lives)

and conduct military duty and training one weekend a month and two weeks annually.91 The Reserve is under the military command and

control of a three-star commander who has single, unified command authority both as the commanding general, U.S.

Army Reserve Command (USARC), and the chief of the Army Reserve (CAR). While USARC is a direct reporting unit to

the U.S. Forces Command, the CAR reports directly to the Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Army.92

This dual mission ensures the Reserve achieves its purpose: to supplement the Regular Army and joint force in an

operational role by providing “trained units and qualified persons available for active duty in the Armed

Forces, in time of war or national emergency” and filling “the needs of the Armed Forces whenever more units and

persons are needed.”93 While the

ARNG shares this same mission, it has a second unique mission: provide trained and equipped Soldiers and units

to the states and territories to protect people and property.94

The ARNG

The ARNG has the same unit structure and equipment as the Regular Army.95 Yet, a key distinction between

the ARNG and Regular Army, relevant to command authority, is their title 32 and title 10 status,

respectively.96 The ARNG

originated from colonial-era militias, which predate the Constitution.97 It is a dual-hatted institution wherein

citizen-Soldiers are primarily mobilized by a state governor to active-duty status to perform a state military

mission or, as discussed more below, are in a title 32 status with Federal pay and benefits.98 Under state sovereignty, both statuses are under

the command and control of the state governor,99 who appoints an adjutant general (TAG)—a general officer—over each ARNG

state and territory as its uniformed leader.100 Each state or territory’s laws prescribe the TAG’s command authority

and duties.101 This authority is

frequently used to respond to domestic emergencies.102 The law provides Federal funding to the ARNG under state authority

while decentralizing and leveraging its sovereignty to conduct domestic operations.103

SVCs and SVC paralegals from all three Army components (active component, Army National Guard,

and Army Reserve) take a break from their SVC Regional Training to pose for a group photo outside the USARLC in

Gaithersburg, MD. (Credit: 1LT Amber Lamb, USARLC)

Separate and apart from the ARNG, state defense forces organized under 32 U.S.C. § 109(c) are generally a state

guard or militia unit wearing military-type uniforms indistinguishable from standard Army uniforms.104 Because militia members

remain under the governor’s command authority, they are not ARNG forces and cannot be federalized.105 However, under applicable

state laws, governors can lawfully issue orders to state defense forces to conduct law enforcement missions.106 Within all the types of

military status, command authority is executed at all levels of command, to various degrees.107

Title 32 is a “middle ground” status between state and Federal operations where, despite being paid with Federal

funds at the President’s request, the ARNG is under the governor’s control.108 However, command authority over the ARNG

changes when units are lawfully federalized;109 like Reserve forces, ARNG Soldiers can also be mobilized in a title 10

status to perform Federal active duty (such as Reserve component training or a Regular Army operational mission)

under the sole command and control of the President and CCDRs by delegation.110 By statute, the President “shall prescribe

regulations, and issue orders necessary to organize, discipline, and govern the National Guard” forces mobilized

in this status.111 This

statutory grant of authority mirrors the authority in the second militia clause, which states that Congress

shall “provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining[] the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as

may be employed in the Service of the United States.”112 These similarities and the unique balance of power between the

executive and legislative branches were underscored in the recent debate over the Justice Department’s Office of

Legal Counsel claims that the Constitution authorizes the President to order a military attack on another

country, without congressional authorization, for self-defense of an imminent attack or other important but

limited interests.113

Title 10 status is an important role for the Reserve component due to the increasing number of times the Federal

Government has involuntarily activated it for contingency operations.114 There have been nine such activations since

1990, “including large-scale mobilizations for the Persian Gulf War (1990-1991) and the aftermath of the

September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks (2001-present), as well as for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic response.”115 Yet

command authority over Reserve component Soldiers on Federal missions is limited by its very nature (title 10,

U.S. Code). For example, Federal military forces cannot assist law enforcement except in limited

circumstances.116 Therefore,

ARNG Soldiers participating in law enforcement missions in a title 32 status fall under a unique command

authority.117

Dual-Status Commanders

The requisite command authority in this title 32 situation is

achieved through the President and governor approving a dual-status commander (DSC) role, where the commanding

military officer serves as both a state National Guard officer under the governor’s control and a Federal Army

officer under the control of the President, SECDEF, and supported COCOM—all at the same time.118 This authority to

simultaneously serve in a state and Federal status provides dual command authority over non-federalized National

Guard forces and federalized forces through two chains of command.119 The commander of the U.S. Northern Command

and the chief of the National Guard Bureau share joint management over DSCs.120 The DSC command authority is specifically

utilized to unify and support state and Federal forces responding to disasters and national events.121 To operate within state law

prohibitions and limits of command authority within each state National Guard, each state is appointed a DSC to

respond to situations that cross state lines.122 However, this structure (unique command authority) is lost in a

deployed environment, where CCDRs only command Service members federalized in a title 10 status under the

President’s chain of command.

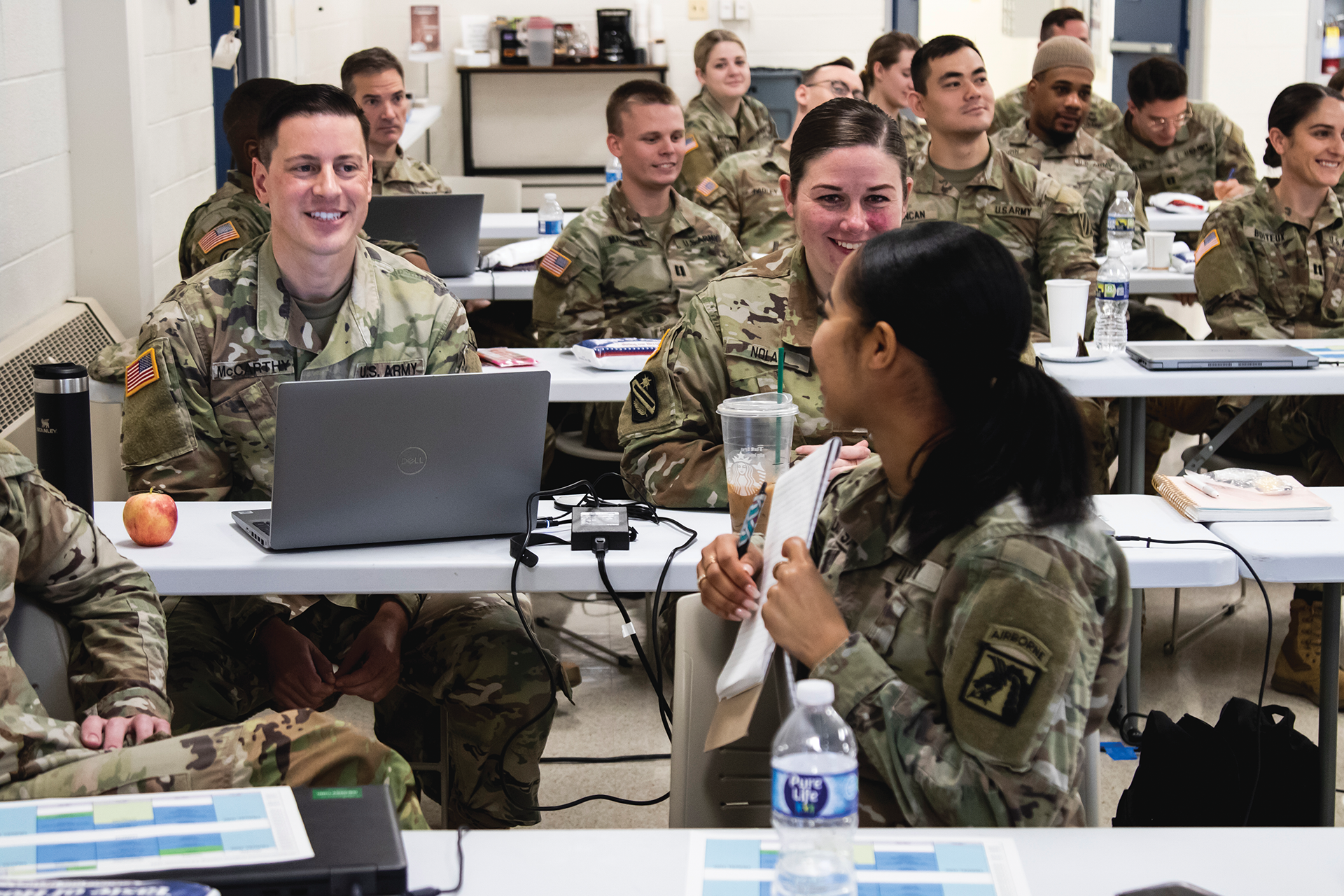

Active and Reserve component attendees discuss their unique experiences during the integrated SVC

Regional Training held 5-7 December 2023 at the USARLC in Gaithersburg, MD. In this photograph, CPT Aldavina

DosSantos, Army SVC (XVIII Airborne Corps, Fort Liberty) (front-right) exchanges ideas with MAJ Keith A.

McCarthy, USAR SVC Northeast regional manager (139th Legal Operations Detachment (LOD)) (left) and SFC Jessica

F. Nolan, USAR SVC paralegal (139th LOD) (right). (Credit: 1LT Amber Lamb, USARLC)

In a Title 10 Status, the National Guard Operates under COCOM

Authority

When mobilized solely to Federal active duty, such as Defense

Support to Civil Authorities, ARNG Soldiers operate under the COCOM authority of CCDRs.123 Under the Goldwater-Nichols Act, CCDRs were

granted the control and authority under OPCON that the Services’ respective chains of command previously

possessed.124 By assigning all

combat forces to unified CCDRs, the Goldwater-Nichols Act removed the Joint Chiefs of Staff from the operational

chain of command.125 While CCDRs

have OPCON over Reservists, they must coordinate with ADCON commanders (e.g., the ARNG title 32 commander with

whom they share ADCON responsibility) on all discipline issues. This is important because, since fiscal year

2014, the Services have been involuntarily activating Reservists to provide global support to COCOMS for planned

missions.126 ADCON is not part

of the command relationship; therefore, discipline matters do not fall within operational missions under

OPCON.127

To support COCOMs, the President can involuntarily activate Reserve units for 365 or fewer consecutive days for

operational missions to respond to “weapon[s] of mass destruction” or “a terrorist attack in the [U.S.

resulting] in significant loss of life or property.”128 Since September 11, 2001, “more than 420,000 Army Reserve Soldiers

were mobilized. [As of 2022], nearly 8,000 Soldiers are deployed to [twenty-three] countries in direct support

of [GCCs] ”129 Sufficient

Reserve component mobilizations under the Federal chain of command is important to CCDRs who rely heavily on the

Reserve component to provide “combat ready resources”130 and “build[] global partnerships” worldwide.131

Commanders Must Know the Key Differences in Law Applicable to Duty

Status

One important limitation on command authority is the bar to using

Federal active Service members for civilian law enforcement (domestic police force) and other domestic

operations without express legal authority in accordance with the Posse Comitatus Act.132 However, the Posse Comitatus Act does not

cover ARNG members in a title 32 status reporting to their governor.133 Although the Posse Comitatus Act prevents the

military from being “a threat to both democracy and personal liberty,”134 statutory exceptions give the President

command authority to direct Service members to suppress rebellion and civil rights violations.135 Even though the DoD has

established policy assigning responsibilities for defense support of civil authorities,136 the courts have not determined whether the

Constitution expressly grants or confers inherent “emergency authority” on military commanders to use Federal

troops “to quell large-scale, unexpected civil disturbances” when “necessary” where presidential authorization

is impossible.137

Whether the Posse Comitatus Act is deemed a source of command authority or limitation depends on whether the

governor ordered the support or the request as part of a larger Federal mission.138 In 2020, the President asked governors to

send ARNG members in a title 32 status (under their respective state’s command and control) into Washington D.C.

to police protests.139 In 2021,

the President’s Acting Defense Secretary authorized thousands of ARNG members to secure the U.S. Capitol area

and help ensure a “peaceful transition of power” to the President-elect.140 This is an unconventional command authority

not typically conferred on the President under the Posse Comitatus Act because, except for the Washington D.C.

National Guard, the ARNG “generally operate under the command of their state or territorial governor” when not

federalized.141 By contrast,

when mobilized to active duty, command and control over ARNG members shifts to Federal commanders.142

Falling under a federalized chain of command can expose Reserve component citizen-Soldiers to unique problems for

which they are afforded protections under the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act143 and SCRA.144 These laws, while applicable to duty status,

do not directly affect command authority over federalized Service members. However, the issues they are designed

to address can negatively impact Reserve component members’ morale and overall effectiveness as a force

multiplier. Therefore, inherent command authority includes the responsibility to manage problems these Soldiers

encounter because of their dual status. Judge advocates can help commanders ensure Soldiers receive the

assistance they need to protect their civil rights and balance their Federal military duty with their civilian

lives. For example, a comprehensive RAND study found that the four most reported issues Reserve component

Families encounter post deployment are the Service member’s “mental or emotional health, health care or medical

issues, . . . civilian employment, and relationship with a spouse or partner.”145 Leaders and JAs should learn about and

recommend reintegration resources (ranging from informal to Federal resources) for Reserve component

Families.146

Active and Reserve component attendees discuss their unique experiences during the integrated SVC

Regional Training held 5-7 December 2023 at the USARLC in Gaithersburg, MD. In this photograph, MAJ Amanda M.

Baylor, USAR SVC deputy program manager (left), enjoys a light-hearted exchange between MAJ Daphne A. Trombley,

USAR SVC Southwest regional manager (1st LOD) (middle) and CPT Gabrielle D. Bloodsaw, Army SVC (Maneuver Center

of Excellence, Fort Moore) (front-right). (Credit: 1LT Amber Lamb, USARLC)

Conclusion

Both the President and Congress govern and regulate the Armed Forces. The President delegates command authority

to Service Secretaries, down to commanding officers and subordinate commanders. This delegation structure

includes COCOMs, which have command authority over ARNG Soldiers on Federal active duty. Significant differences

in command authority exist among the Regular Army, ARNG, and Reserve. Reserve component mission command

authority stems from Congress’s legislative framework of training, funding, and personnel law unique to these

two components. Congress funds and equips the Reserve component and can “adjust Reserve activation

authorities,”147 but its broad

power over the Armed Forces should not unduly restrict the President’s command authority.

Commanders’ powers and responsibilities are based on whether their Soldiers are serving in a title 32 versus

title 10 status; each status comes with its own set of command authority. Senior JAs must help commanders

acknowledge the differences between these populations both in the source of the command authority over them and

in the concerns they bring with them on Federal active duty. This is important given that the Reserve component

will likely continue to mobilize in large numbers for Federal operations,148 as it has been transformed since the Cold War

Era from a last-resort force to an integral force multiplier.149 Commanders need legal advice on matters requiring their exercise of

discretion, judgment, inherent authority, and assumption of risk while making decisions. They must know the

designated command roles to determine applicable legal authorities and responsibilities.150 Judge advocates from all components must be

prepared to advise commanders in operational environments that will include federalized ARNG and Reserve members

transitioning from citizen-Soldier roles to active duty.151

Students in the 72d Graduate Course participate in a game of ultimate frisbee at The Judge

Advocate General’s Legal Center and School in Charlottesville, VA. (Credit: MAJ Jonathan L. Kopecky)

Notes

1. Deployable Training Div., Joint Staff J7 and Best

Practices Focus Paper: Authorities 2 (2d ed. 2016) [hereinafter Authorities].

2. National Defense Act Amendments, Pub. L. No. 66-242, 41

Stat. 759, 759 (1920) (codified in scattered sections of 10 U.S.C.). These are commonly referred to as:

Regular Army – COMPO 1; U.S. Army National Guard – COMPO 2; and U.S. Army Reserve – COMPO 3. Army Nat’l

Guard Bureau, Reg. 7 National Guard Force Program Review para (5 Apr. 2022) (C1, 27 Feb. 2023).

3. See U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 600-20, Army Command Policy

para. 1-4(i) (24 July 2020) [here 600-20].

4. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 6-22, Army Leadership

and the Profession para. 1-9 (C1, 25 Nov. 2019) [hereinafter ADP 6-22]

5. David R. Graham et al., Tailoring Active Duty

Commitments for Reserve Component Service Members, in U.S Dep’t of Def., The Eleventh Quadrennial

REVIEW OF MILITARY COMPENSATION 647 (2012); U.S. Dep’t of DEF, Military Compensation Background Papers:

Compensation Elements and related manpower cost items, at i (8th ed. 2018); see also Lawrence Kapp & Barbara

salazar Salazar Torreon, Cong. Rsch. Serv., RL 30802, Reserve Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Queations

and answers Answers 7, 29 (25th ed. 2021) [hereinafter Personnel issues] Issues] (describing the large

mobilization of reservists that has occurred since 2001 and explaining that, due to increased mobilizations

of the Reserve component in past years, Congress enacted new laws allowing reservists to retire before age

sixty).

6. This assertion is based on the author’s recent

professional experiences as the U.S. Army Reserve Special Victims’ Counsel Program Manager from 3 June 2023

to 12 June 2024.

7. Authorities, supra note 1, at 2.

8. See id.

9. See ADP 6-22, supra note 4, para. 1-96.

10. See Richard M. Swain & Albert C. Armed Forces

Officer 77 (2017) (quoting Dep’t, Field Service Regulations, United (1923)).

11. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 6-0, Commander and

Staff Organization and Operations, at vii (16 May 2022).

12. 10 U.S.C. § 164(c).

13. ADP 6-22, supra note 4, para. 1-95.

14. See id. para. 1-97

15. Authorities, supra note 1, at 4; see

also 10 U.S.C. § 164(c)(3) (“If a commander of a combatant command at any time considers his authority,

direction, or control with respect to any of the commands or forces assigned to the command to be

insufficient to command effectively, the commander shall promptly inform the Secretary of Defense.”).

16. U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 1.

17. Id. art. I, § 8, cl. 14 (original style

retained).

18. Thomas W. Stone, Military Command Authority: A

Phenomenological Study of How U.S. Army Company-Grade Leaders Experience Insubordination 18, 45, 49 (2022)

(Ph. D. dissertation, Liberty University) (on file with Liberty University). By authority derived from title

10, U.S. Code, the Secretary of the Army directly delegates command authority over Army installations.

See AR 600-20, supra note 3, para. 2-5.

19. See U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 1, The

army para. 1-9 (31 July 2019) [hereinafter ADP 1].

20. Although “Reserve component” includes seven Reserve

components of the Armed Forces (Army Reserve, Air Force Reserve, Navy Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve, Coast

Guard Reserve, Army National Guard of the United States, and Air National Guard of the United States),

Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at Summary, this paper will focus solely on the Army National Guard

of the United States and the Army Reserve.

21. See id. (discussing unique Reserve component

training, funding, and personnel policies).

22. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Pub. 1-0, Joint Personnel

Support, at i (1 Dec. 2020).

23. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8 (original style retained).

24. Servicemembers Civil Relief Act of 2003 (SCRA), Pub.

L. No. 108-189, 117 Stat. 2835 (codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 3901-4043).

25. Jennifer K. Elsea et al., Cong. Rsch. serv., R41989,

Congressional Authority to Limit military Operations 2 (2d ed. 2013) [hereinafter Military Operations].

Congress recently enacted a major limitation on command authority by removing the power of commanders to

exercise authority over sexual assault, sexual harassment, and other covered offenses. See National

Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Pub. L. No. 117–81, sec. 533, 135 Stat. 1541, 1695 (2022).

The Secretary of the Army was directed to stand up a new division of special trial counsel. Id. The

Lead Special Trial Counsel supervises the Office of Special Trial Counsel as a direct report to the

Secretary of the Army. Headquarters, U.S. Dep’t of Army, Gen. Order No. 2022-10 (6 July 2022); see

also UCMJ art. 824a (2022). This takes prosecuting sexual assault and all covered offenses out of the

operational chain of command. Another example of limitations on command authority is the Army directive

barring commanders from disciplining sexual assault victims for minor collateral misconduct. U.S. Dep’t of

Army, Dir. 2022-10, Safe-to-Report for Victims of sexual Assault para. 4 (6 July 2022); see also

William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283,

sec. 539A, 134 Stat. 3388, 3607 (2021) (codified in scattered sections of 10 U.S.C.)

26. Military Operations, supra note 25, passim

(explaining that Congress could use its war powers or powers of the purse to restrict or terminate U.S.

participation in operations or hostilities).

27. U.S. Const. art. II, § 2 (original style retained).

28. Id.

29. See id. The President’s broad authority

includes commissioning U.S. officers. Id. art. II, § 3.

30. See generally id. art. II, § 1.

31. Swain & Pierce, supra note 10, at 83.

32. Military Operations, supra note 25, at 22.

33. Swain & Pierce, supra note 10, at 83.

34. See Abigail A. Graber, Cong. Rsch. Serv.

R46738, Executive Ordrs: An Introduction (5th ed. 2021). As a prime example of EO action, the President

implements statutory military law (UCMJ) through the Manual for Courts-Martial (MCM). Manual for

Courts-Martial, United States (2024). First promulgated as Exec. Order No. 12473, 49 Fed. Re (Apr. 13,

1984), the MCM contains five parts and twenty-two appendices.

35. Recent examples of how Presidents have commanded the

Armed Forces both illustrate how they have viewed and exercised their command authority and carry the

separation of powers debate into modern-day scenarios. Jennifer K. Elsea, Cong. rsch. Serv., IF10534,

Defense Primer: President’s Constitutional Authority with Regard to the armed forces (10th ed. 2022)

[hereinafter Presidential Authority]. In 2011, President Obama “ordered U.S. military forces to take action

as part of an international coalition to enforce U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973”; in 2018, President

Trump “ordered airstrikes against three chemical weapons facilities in Syria, where U.S. troops were engaged

in armed conflict against the Islamic State”; in 2020, President Trump “ordered a strike against an Iranian

target in Iraq, killing Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force”; and

in 2021, President Biden “ordered airstrikes against Iran-backed militia targets in Iraq and Syria in

response to rocket attacks against U.S. targets in Iraq.” Id. at 2. President Clinton argued he had

constitutional authority as Commander in Chief to use military force to protect the Nation and national

interests, and President Biden argued he had the same authority to conduct foreign relations and did not

need Congress’s authorization to use military force. Id.; see also Robert Dallek, Power and Presidency,

from Kennedy to Obama, Smithsonian, Jan. 2011, at 36.

36. Executive Orders, Heritage Explains,

https://www.heritage.org/political-process/heritage-explains/executive-orders (last visited Mar. 6,

2024).

37. See Zachary S. Price, Congress’s Power over

Military Offices, 99 Texas L. Rev. 491, 504, 541 (2021) (discussing how Congress has recognized the

President’s command authority under the Constitution).

38. Military Operations, supra note 25, at 34,

36.

39. See Presidential Authority, supra note 35, at

2.

40. Id.

41. The Executive Branch, Pol’y Circle,

https://www.thepolicycircle.org/brief/the-executive-branch/#section_3 (last visited Mar. 6, 2024)

[hereinafter Pol’ Circle].

42. This concept applies similarly at the state level

when, during times of crisis (such as natural disasters or public health emergencies), governors with

already sweeping powers temporarily exercise expanded executive powers into roles typically reserved for

legislatures (e.g., waiving statutory requirements). See id.

43. War Powers Resolution of 1973, Richard Nixon

Presidential Libr. & Museum (July 27, 2021), ht nixonlibrary.gov/news/war-powers-resolution-1973 (discussing

the War Powers Resolution of 1973, “a congressional resolution designed to limit the U.S. [P] resident’s

ability to initiate or escalate military actions abroad”).

44. See U.S. Const. arts. I, II.

45. See Delegation of Legislative Power,

JUSTIA,

https://law.justia.com/constitution/us/article-1/04-delegation-legislative-power.html (last visited

Mar. 6, 2024) (detailing the legislature’s ability to delegate its power).

46. See Authorities, supra note 1, at 1.

47. 3 U.S.C. § 301.

48. Exec. Order No. 12765, 56 Fed. Reg. 27401 (June 11,

1991). While the President can also effectively use EOs for policymaking, regular turnover across the

executive branch can disrupt the exercise of delegated command and prevent high-level commanders from

tackling major challenges facing the Department of Defense and Services. See Pol’y Circle, supra

note 41 (describing how a sitting President can overturn a previous President’s EO with “the stroke of a

pen”).

49. 10 U.S.C. § 164.

50. See 10 U.S.C. § 162; Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), Joint Chiefs of Staff,

https://www.jmil/About/The-Joint-Staff/Chairman (last visited May 22, 2024).

51. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 3-94, Armies, Corps,

and Division Operations para. 1-87 (23 july 2021) [hereinafter FM 3-94].

52. Deployable Training Div., Joint Staff J7, Insights and

Best Practices Focus Paper: JTF C2 and Organization 2(2017).

53. Id. For purposes other than OPCON, the

President’s chain of command runs through the SECDEF to the SECARMY who has administrative control (ADCON)

of all Department of the Army members for institutional (support) missions. Id.; Understanding the

Army’s Structure, U.S. Army,

https://www.army.mil/organization (last visited Mar. 6, 2024).

54. See 10 U.S.C. § 164(c)-(e); Andrew Feickert &

Barbara Salazar Torreon, Cong. Rs Defense Primer: Department of the Army and army Command Structure (11th

ed. 2024); Combatant Commands, U.S. Dep’t of Def., https://www.defense.gov/About/Combatant-Commands (last visited May 22, 2024).

55. 10 U.S.C. § 164(a)-(b); U.S. Dep’t of Def., Dir.

5100.01, Functions of the Department of Defense and Its Major Components para. 4(b)(3) (21 Dec. 2010 (C1, 17

Sept. 2020).

56. 10 U.S.C. § 164(c)(2)(A). The Secretary of Defense

assigns the CJCS to oversee COCOM operations. See Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Pub. 3-35, Joint

Deployment and Redeployment Operations, a 2022).

57. 10 U.S.C. § 164(c)(E).

58. Joint Chiefs of Staff, DoD Dictionary of Military and

Associated Terms 33 (2024) (defining “combatant command (command authority)”).

59. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 3-28, defense

Support of Civil Authorities para. 4-24 (31 July 2019) [hereinafter ADP 3-28].

60. Authorities, supra note 1, at 3.

61. Id. “These matters normally remain within the

title 10 authorities of the various armed [S]ervice branches.” Id. Within OPCON, tactical control

(TACON) of assigned or attached forces is delegable to subordinate commanders and limited to the “detailed

and, usually, local direction and control of movements or maneuvers necessary to accomplish missions or

tasks assigned.” Id.

62. See FM 3-94, supra note 51, para.

1-87 (“The [ADCON] chain of command runs from the President to the Secretary of Defense, to the secretaries

of the Military Departments, and, as prescribed by the secretaries to the service commanders of U.S. forces.

Each Military Department operates under the authority, direction, and control of the secretary of that

Military Department.”).

63. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 3-0, Operations, at

4-60 (1 Oct. 2022) [hereinafter FM 3-0]; U.S. Dep't of Army, Reg. 10-87, Army Commands, Army Service

Component Commands, and Direct Reporting Units para. 1-1(f)(4) (11 Dec. 2017) [hereinafter AR 10-87].

64. AR 10-87, supra note 63, para. 1-1(f), (g)

65. Unified Commands, CENTCOM & Components, U.S

Cent. Command,

https://www.centcom.mil/ABOUTUS/COMPONENT-COMMANDS (last visited May 21, 2024).

66. See U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 3-84,

Legal Support to Operations paras. 2-33 to 2-35 (1 Sept. 2023) [hereinafter FM 3-84].

67. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-16-652R, Defense

Headquarters: Geographic Combatant Commands Rely on Subordinate Com Management and Execution 2 (2016).

68. Ufot B. Inamete, The Unified Combatant Command

System, Marine Corps Univ. Press (J 7, 2022),

https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Expeditions-with-MCUP-digital-journal/The-Unified-Combatant-Command-System.

69. See Andrew Feickert & Lawrence Kapp, Cong.

Rsch. Serv., R43808, Army Active Component (AC)/ Reserve Component (RC) Force Mix: Considerations and

Options for Congress 2 (3d ed. 2014) [hereinafter AC/RC]. Reserve component units called to active duty or

Federal service in the continental United States fall under their relative U.S. Army command (e.g.,

FORSCOM). FM 3-84, supra note 66, app. B, para. B-1.

70. Rsrv. Forces Pol’y Bd., RFPB Report FY 1701, Improving

the Total Force Using the National Guard and Reserves 54 (2016).

71. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Pub. 3-30, Joint Air

Operations, at I-3 (17 Sept. 2021).

72. ADP 1, supra note 19, para. 2-37.

73. Deployable Training Div., Joint Staff J7, Insights and

Best Practices Focus Paper: Mission Command 1 (2d ed. 2020).

74. Id.

75. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 6-0, mission

Command: Command and Control of Army Forces para. 1-14 (31 July 2019) [hereinafter ADP 6-0].

76. Authorities, supra note 1, at 7.

77. ADP 6-0, supra note 75, para. 1-77.

78. Exec. Order No. 12333, 46 Fed. Reg. 59941 (Dec. 4,

1981).

79. See U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 5-0,

The Operations Process para. 1-37 (31 July 2019) (explainin that “[c]ommanders describe their visualization

in doctrinal terms” through OPORDs and FRAGORDs). As a tool for mission planning and execution, commanders

can use an authorities matrix to identify authorities granted and required. Authorities, supra note

1, at 8.

80. See AR 600-20, supra note 3, para.

2-1.

81. ADP 6-0, supra note 75, at vii (explaining

that “[t]hrough command and control, commanders provide purpose and direction to integrate all military

activities towards a common goal—mission accomplishment”).

82. See AR 600-20, supra note 3, para.

2-5. This includes taking corrective measures such as directing a deficient Soldier to undergo more training

or instruction. See id. para. 4-6; Memorandum from Sec’y Def. to Senior Pentagon Leadership et al.,

subject: Rescission of August 24, 2021 and November 30, 2021 Coronovirus Disease 2019 Vaccination

Requirements for Members of the Armed Forces (10 Jan. 2023).

83. AR 600-20, supra note 3, para. 5-2(b)(2)(d).

84. FM 3-84, supra note 66, para. 2-36.

85. ADP 1, supra note 19, paras. 1-8, 1-11.

86. See FM 3-94, supra note 51, para.

3-2.

87. See U.S. Army Rsrv., 2012 Posture Statement,

an Enduring Operational Army Reserve: Providing Indispensable Capabilities to the total force 5 (2012).

88. FM 3-84, supra note 66, para. 2-36.

89. U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 12; Personnel Issues,

supra note 5, at 6.

90. Army Reserve, Today’s Mil.,

https://wwtodaysmilitary.com/ways-to-serve/service-branches/army-reserve (last visited Mar. 11,

2024).

91. See Personnel Issues, supra note 5,

at 1-3.

92. 10 U.S.C. § 7038; Headquarters, Dep’t of Army, Gen.

Order No. 2011-02 (4 June 2011) (“Redesignation and Assignment of the United States Army Reserve Command as

a Subordinate Command of the United States Army Forces Command”)

93. 10 U.S.C. § 10102.

94. See About the Guard, Nat’l Guard,

https://www.nationalguard.mil/About-the-Guard (last visited May 21, 2024).

95. FM 3-84, supra note 66, para. 2-36. “Unlike

the active component’s two-year cycle, the transitional cycles for the Army Reserve consist of one year of

modernization and three years of training, followed by a one-year mission.” U.S. Army Rsrv., 2022 Posture

Statement, America’s Global Operational reserve Force 8 (2022) [hereinafter 2022 Posture Statement].

96. Supra note 84 and accompanying text.

97.Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at 6.

98. ADP 1, supra note 19, para. 1-9. A state

military mission example is civil disorder response. See id.

99. Id.

100. Id.; 32 U.S.C. § 314.

101. See 32 U.S.C. § 314.

102. Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at 1.

103. Jeffrey W. Burkett, Command and Control of

Military Forces in the Homeland, 51 Joint Force Q.,4th Quarter, 2008, at 130, 131. The Secretary of

Defense can “provide funds to a [g]overnor to employ National Guard units or members to conduct homeland

defense activities.” 32 U.S.C. § 902.

104. 32 U.S.C. § 109(c); ADP 3-28, supra note

59, para. 3-20; see also U.S. Dep’t of Def., Dir. 5105.83, National Guard Joint Force

Headquarters-State(NG JFHQs-State) (5 Jan. 2011) (C2, 31 Mar. 2020).

105. ADP 3-28, supra note 59, para. 3-20.

106. Id.

107. See, e.g., AR 600-20, supra note

3, para. 2-1.

108. Joseph Nunn, The Posse Comitatus Act

Explained, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Oct. 14, 2021),

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/posse-comitatus-act-explained. This issue is

explored later in this article. When non-federalized members of the ARNG participate in joint training or

maneuver with Regular Army or Reserve members in a Federal status, command authority remains only with

applicable Federal officers, regardless of any higher rank of participating ARNG members. 32 U.S.C. § 317.

109. ADP 3-28, supra note 59, para. 2-54.

110. Id.; see also 10 U.S.C. §§ 10105, 12406.

This is an important distinction between the Regular Army as a pure Federal entity and the ARNG as both a

Federal and state entity. See Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at 15.

111. 32 U.S.C. § 110.

112. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 16 (original style

retained).

113. See Charlie Savage, Presidential War

Powers: Ordering Military Attacks without Congress, N.Y. Times (Sept 9, 2019),

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/us/politics/presidential-war-powers-executive-power. html.

114. U.S. Govt Accountability Off., GAO-09-688R,

Military Personnel: Reserve Component Servicemembers on Average Earn More Inc 1 (2009) (explaining that

because of the Reserve component’s increased contingency operations, Congress directed a review of the

Reserve component’s compensation while serving on active duty); see also Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at

Summary; 10 U.S.C. § 12301.

115. Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at

Summary.

116. See 18 U.S.C. § 1385.

117. Christopher M. Schnaubelt, The National Guard

Can Do It, but That Doesn’t Mean It’s a Good Idea, Mil. Times (Mar. 18, 2021),

https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2021/03/18/the-national-guard-can-do-it-but-that-doesnt-mean-its-a-good-idea

118. Nat’l Guard, Dual Status Commander (DSC) Fact Sheet

(n.d) [hereinafter DSC FACT SHEET],

https://www.nationalguard.mil/Portals/31/Resources/Fact%20Sheets/DSC%20Fact%20Sheet%20(Nov.%202020).pdf.

119. Id. (explaining that a DSC is a member of

the Army National Guard and a commissioned officer in the Regular Army and must receive specialized

training to become certified for the role).

120. Id.

121. ADP 3-28, supra note 59, para. 3-57.

122. DSC Fact Sheet, supra note 118.

123. ADP 3-28, supra note 59, paras. 2-51,

3-48, 4-24.

124. See Goldwater–Nichols Department of

Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-433, § 211, 100 Stat. 992, 1011 (1986).

125. See The Joint Staff, The Joint Staff, https://www.jcs.mil/About (last visited Mar. 11,

2024).

126. Personnel Issues, supra note 5, at

Summary; see also FM 3-0, supra note 63, para. B-5.

127. Andre M. Coln, Command Authority: A Guide for

Senior Enlisted Leaders, NCO J., Oct. 2022, at 1; AR 10-87, supra note 63, para.

1-1(f)(4)(a); see also U.S. DEP'T of Def., 8260.03-V2, Global Force Management Data Initiative (GFM DI)

Implementation: The Organizational and Force Structure Construct(OFSC)encl. 3, fig.1 (14 July 2011).

128. 10 U.S.C. § 12304(a)-(b).

129. 2022 Posture Statement, supra note 95, at

2.

130. U.S. National Guard’s Domestic and Global

Engagement: FPC Briefing: General Daniel R. Hokanson, Chief of the National Guard Bureau, U.S.

Dep’t of state (Sept. 8, 2022),

https://www.state.gov/briefings-foreign-press-centers/national-guard-domestic-and-global-engagement.

131. Jim Greenhill, Combatant Commanders: National

Guard Builds Global Partnerships, Proven on Battlefield, Nat’l Guard (Mar. 7, 2014),

https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/575557/combatant-commanders-national-guard-builds-global-partner-ships-proven-on-battle.

132. Jennifer K. Elsea, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R42659, The

Posse Comitats Act and Related matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law(8th ed. 2018)

[hereinafter Posse Comitatus]; see also 18 U.S.C § 1385.

133. Nunn, supra note 108.

134. Id.

135. See Joseph Nunn, The Insurrection Act

Explained, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Apr. 21, 2022), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/insurrection-act-explained.

136. See U.S. Dep’t of Def., Dir. 3025.18,

Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) (29 Dec. 2010) (C2, 19 Mar. 2018).

137. Id. para. 4(k); see also Nunn,

supra note 108.

138. Posse Comitatus. supra note 132.

139. Nunn, supra note 108.

140. Jim Garamone, DoD Details National Guard

Response to Capitol Attack, Nat’l Guard (Jan.8, 2021),

https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/2466077/dod-details-national-guard-response-to-capitol-attack.

141. Elizabeth Goitein & Joseph Nunn, DC’s National

Guard Should Be Controlled by Its Mayor, Not by a President Like Trump, Brennan Ctr. for Just.

(Dec. 3 2021),

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/dcs-national-guard-should-be-controlled-its-mayor-not-president-trump.

142. See supra notes 110-112 and accompanying

text.

143. Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment

Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA), Pub. L. No. 103-353, sec. 2(a), 108 Stat. 3149, 3149 (codified at 38 U.S.C. §§

4301-4334).

144. Servicemembers Civil Relief Act of 2003 (SCRA),

Pub. L. No. 108-189, 117 Stat. 2835 (codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 3901-4043).

145. Laura Werber et al., RAND Corp.,support for the

21st-Century Reserve Force: Insights to Facilitate Successful Reintegrati and Their Families 56-57 (2013).

146.See id. at 119-20.

147. AC/RC, supra note 69, at 2.

148./a> See U.S. Army Rsrv., 2012 Posture

Statement, an Enduring Operational Army Reserve: Providing Indispensable Capabilities to the Michael E.

Linick et. al, RAND Corp., RR-1516-OSD, A Throughput-Based Analysis of Army Active Component/Reserve

Component Mix for Major Contingency Surge, at ix (2019).

149. See Kathryn R. Coker, U.S. Army R

Indispensable Force: The Post-Cold Wa Army Reserve, 1990-2010, at 360 (Lee S. Harford, Jr. e al. eds.,

2013); James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117- 263, 136

Stat. 2395 (2022) (authorizing the President’s requested end strengths for the Reserve component and

limiting two exceptions to FY2022 levels).

150. See Authorities, supra note 1, a

2.

151. See FM 3-84, supra note 66, para.

2-12.

Author

Major Baylor is the Deputy Command Judge Advocate at the 102d Training Division at Fort Leonard Wood,

Missouri.