Conversation Curveballs

A Trauma-Informed Communication Skills Toolkit to Enhance JAG Corps Health &

Well-Being

By Elizabeth F. Pillsbury, LICSW

Article published on: January 1, 2024 in the Army Lawyer issue 2 2024 Edition

Read Time: < 21 mins

(Credit: Brian Jackson -stock.adobe.com)

The U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps recently created the Wellness Program Director position as a

part of the effort to expand holistic health. As the new Wellness Program Director, I learned within the first

few months of taking on my role that military legal professionals, particularly those with experience in

military justice, regularly handle sensitive and potentially traumatizing information. As a psychotherapist who

has been in practice for nearly twenty-five years and specializes in trauma (to include child abuse, sexual

violence, combat trauma and everything in between), I began reflecting on specific characteristics of

communication that relate to wellness within the Army Judge Advocate Legal Services (JALS) community.

In this article, I offer some of these reflections as a mini communication skills toolkit with the hope of

increasing our trauma-informed practices within the JAG Corps. My goal is to provide real-world applications of

practical tools to respond to everyday situations you may encounter in a way that is compassionate and based on

the mental health field’s best practices.

Trauma-Informed Practice: The Foundation of the Solution

Trauma-informed care is a universal framework that any organization can implement to build a

culture that acknowledges and anticipates that many people we serve or interact with have histories of trauma,

and that the environment and interpersonal interactions within an organization can exacerbate the physical,

mental, and behavioral manifestations of trauma.1

The term “trauma-informed care” or practice may not be new to you or the JAG Corps. It is a widely accepted

framework in the health services, education, and legal professions. An American Bar Association article

discusses the concept in the legal context: “Establishing a trauma-informed law practice is a two-fold process:

(1) taking steps that help prevent re-traumatization of our clients, and (2) taking steps that protect lawyers’

health and well-being from exposure to trauma.”2 Regarding the second arm of this process in

particular, we have room to expand our efforts and further consider ways to be sensitive to the needs of those

in our ranks who may have experienced adversity impacting their health, well-being, or ability to perform at

their highest level. The following communication skills offer concrete ways to do so.

Problem 1: Sharing potentially upsetting stories without warning someone of

what you are about to say.

One of the first stories a judge advocate (JA) shared with me involved a child abuse case that several members of

our military judiciary were exposed to while preparing for and conducting a court-martial. The individual shared

this story to help me understand some of the challenges that JALS personnel face daily and to inform my Wellness

Program development efforts. However, he recounted the story immediately after discussion of a completely

unrelated topic and without warning. The conversation shifted so suddenly that I was unprepared to hear such

information. After he finished the account, the conversation shifted to a different, unrelated topic just as

suddenly. The story’s content was not the most disturbing aspect of the interaction; rather, it was how abruptly

the story was interwoven with an otherwise benign subject matter.

The second incident occurred about a week later at a training session focused on healthy ways to manage

work-related stress, such as playing frisbee with a pet dog in the park. We then had a ten-minute break.

When I returned from the break, I inadvertently entered an on-going conversation about crime scene responses. The

course attendees casually shared “war stories” about their cases. One individual then launched into a detailed

monologue of a recent violent incident. I found myself dealing with a sudden mental shift from the discussion

about playful puppies to processing objectively appalling details.

Solution to Problem 1: Give a “warning shot” before sharing something a

listener may perceive as upsetting or traumatic.

The tricky part about this solution is being aware that what you are going to say may be upsetting to someone

else. Many legal professionals have been in this field for so long and/or have been exposed to so many difficult

stories and evidence that they may be desensitized to sensitive content. They may even think these types of

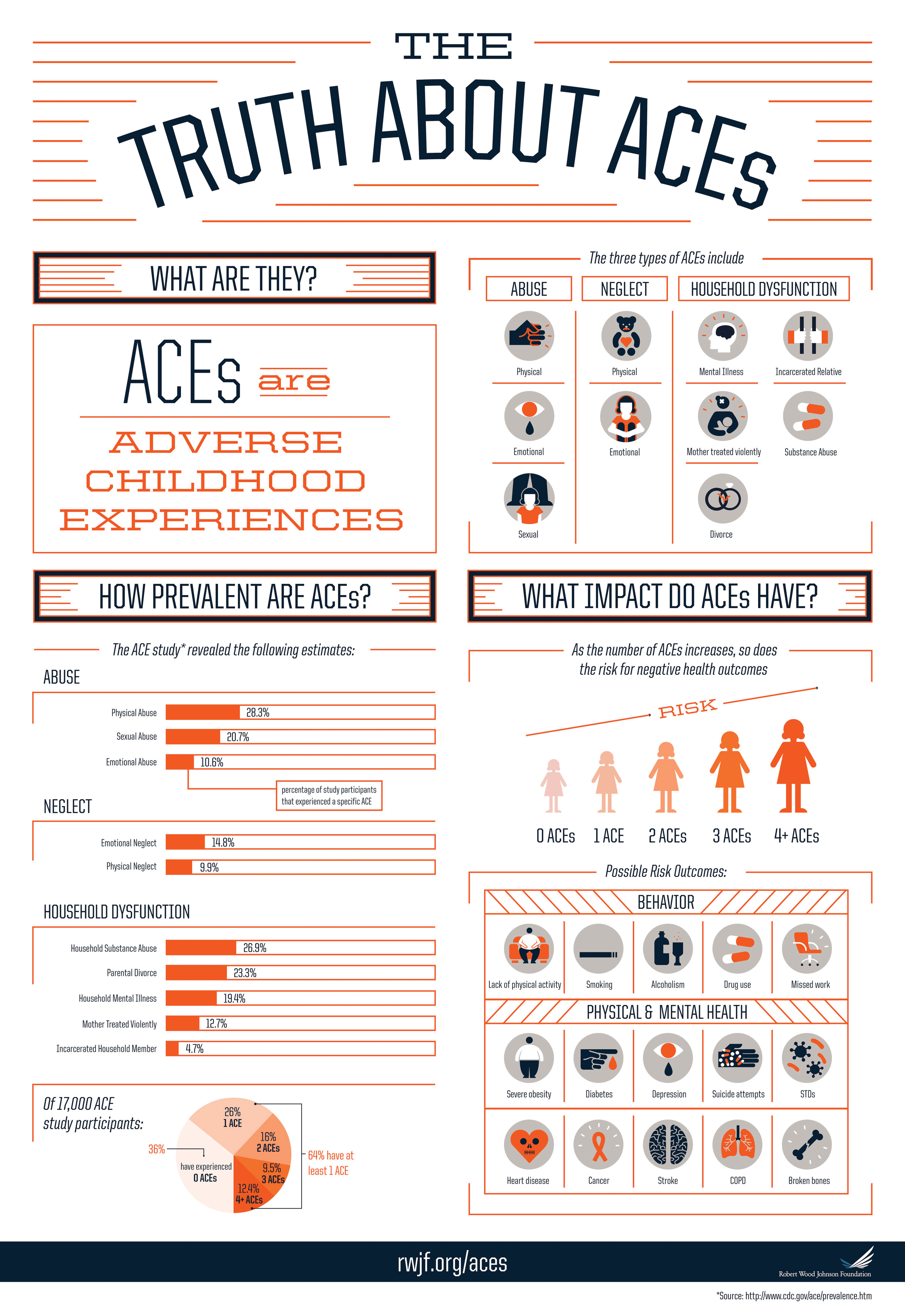

things are “normal” and “routine” because it is what they do daily. Despite the alarmingly high rates of adverse

childhood events (ACEs) in our country and world, these experiences are not normal, and most people outside of

service professions—such as law, healthcare, and education—do not typically see nor hear about these things on a

routine basis.

Ms. Beth Pillsbury. (Image courtesy of author)

Using specific communication tools, including warning someone that you are about to cross into potentially

upsetting or traumatic territory, is a specific trauma-informed practice. This is a tool I have taught doctors

to use for years. Despite having the best intentions, I have seen far too many doctors “sucker punch” their

patients with bad news. I have seen this happen in “practice” encounters and real-life medical appointments.

Once given this tool, they can share potentially life-changing negative news in a way that is compassionate and

sensitive to their patients’ needs. This skill can be taught and learned not just in medicine but in the legal

profession as well.9

The “warning shot” allows the person hearing the story or news to psychologically brace for what is to come. The

storyteller sends a signal for the listener to get ready. The listener’s brain responds, “Okay, time to protect

myself; something bad is coming.” When we are not given the warning shot, our brains automatically shift into

survival mode, which limits our ability to understand the information and process it in a useful and meaningful

way.

Here are some lines to try:

“Unfortunately, . . .”

“I need to share something that may be upsetting to hear.”

“I’m warning you that I’m going to tell you something that may be unpleasant/disturbing to hear.”

Problem 2: Sharing graphic details puts the listener at risk for a negative

reaction and, at times, secondary trauma. It can also put the storyteller at risk for a strong physical

or emotional reaction.

Back to my chat on day one with my JA colleague. I have heard thousands of accounts of abuse, neglect,

interpersonal violence, and all that can result from these experiences. I am trained to sit with people in pain

and tolerate their emotions. Nonetheless, I struggle with the detailed content of their stories, even when I

know they are coming. When the colleague started to recount the child abuse, he included vivid, graphic, sensory

details to help me understand the situation. In the second story, the course attendee also used graphic details

to convey the event’s impact.

Sensory material (sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell) can elicit strong, often involuntary responses in us.

The danger in using this type of detail in storytelling is that once you start to describe something using

sensory material, a person’s brain can start to fill in the gaps—often inaccurately because of the part of the

brain that engages with this type of information. Then, the brain can get stuck. I have heard many say, “I can’t

unsee the things I’ve seen.” This is the same sentiment; the details can remain long after the conversation

ends.

I do not believe most people share these types of stories to upset or traumatize the listener. Rather, they are

often trying to make sense of the experience, looking for support and empathy, or determining whether they have

an accurate account of what happened. However, there are ways to accomplish these tasks without potentially

doing more harm.

Solution to Problem 2: Unless it is necessary and within the correct context

(time and place), consider telling stories and sharing information without using vivid sensory

descriptions and try to talk more about the impact of the information instead.

If you are describing something in detail, your listener can likely see/hear/smell/feel/taste it too. That is

wonderful if you are talking about an amazing trip you took or a delicious meal someone prepared for you—not so

much if you are in a social setting and begin to casually provide details about a difficult case you are working

on. It does not have to be that severe; it could seem routine to you but be upsetting to your audience.

This solution may run counter to the legal field’s culture, in which you are trained to provide detailed

evidence. While that is appropriate in the context of an investigation, evidence collection, deposition, or

courtroom, it is not best practice for everyday conversation.

It is not a good idea to use even when sharing how challenging your work is to someone who cares about you. They

can support you without knowing a case’s details, and conversely, you can unload your experiences without

risking traumatizing the person listening to you. In group therapy with trauma survivors, one of our ground

rules is not to provide so much graphic detail that other people in the group can picture it themselves. The

same rule can be applied to legal work.

I am not encouraging people to remain silent about their experiences; rather, I am encouraging people to share

them in a way that allows for support without threatening the listener’s well-being. If this feels inadequate to

you, I strongly recommend speaking with someone trained to guide you through this process in a safe setting with

scientifically grounded techniques (i.e., a therapist experienced in working with trauma).

Additional Solution to Problem 2: If you do need to share graphic details on

something potentially traumatic, give a warning shot first (and consider asking permission). Here are a

few lines you can try:

“I need to talk about some of the details of the case to give you an understanding of the severity of what

happened. This may be hard to hear. Are you okay with that?”

“Unfortunately, I need to tell you something that may be upsetting. Is now a good time to discuss this?”

Problem 3: Someone’s expression, body language, or nonverbal communication

does not match their story’s severity.

As my colleague recounted his difficult story, he avoided making eye contact, and his gaze looked a million miles

away. His face was flat and expressionless. His voice was nearly monotone and steady, with little to no emotion

in it. He shared that he was deeply concerned about his colleagues, yet his nonverbal communication did not

match.

Similarly, the course attendee told his story about responding to the crime scene from a detached perspective;

his tone did not match what he was recounting. He sounded like he was talking about something as mundane as the

weather rather than the scene he described.

In the therapy world, we call this an “incongruent affect,” or when someone’s expression does not match their

words. Both are concerning to me as a therapist because they may be experiencing signs of depression or

secondary- (or post-) traumatic stress, such as emotional numbness and cynicism. While these can be protective

ways to manage hard, overwhelming feelings in the short term, they can be dangerous in the long term. The more

detached and numb a person is, the longer it can take them to work through these experiences and the higher

their risk for more symptoms of secondary- or post-traumatic stress.

Solution to Problem 3: If someone’s body language and nonverbal communication

do not match what they are saying, consider it an opportunity to offer support.

This may be incredibly challenging in a work setting, particularly with someone with whom you are not close.

If it is a peer or near-peer with whom you do not have a close relationship, consider asking someone who knows

them or works closely with them to reach out and check in with them.

Here is an example of how to bring this up:

“Sir/Ma’am, I have some concerns about how one of my peers is doing, but I don’t feel it’s appropriate

(or I don’t feel comfortable) for me to talk with them about it directly. Could you please offer some guidance

and support? I’ve noticed that he/she hasn’t been acting like his/her usual self, and I’m concerned about

his/her well-being. I respectfully ask if you would reach out to him/her to check in on how he/she is doing.”

Even if the person is someone you are close with, you may feel awkward about this and not know what to say.

Sometimes, it is as simple as telling someone, “I can’t imagine what you’re going through. I’m here with

you.”

Other times, it may be more of a discussion about ways you can support them. You can open a discussion with one

of these:

“Wow, you just told me about something really powerful, but it was like you were somewhere else. . . .

Are you okay?”

“Thanks for sharing that with me. As you were talking about something really upsetting, I noticed that

you seemed really calm. What’s going on inside?”

“Thanks for telling me about this. I can’t imagine what that was like for you. I wish I had the tools to

help you more with it. Would you like me to help you find someone who helps people with these kinds of

experiences?”

(Credit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation)

In the case of someone who outranks you, consider reaching out to someone who is a peer to them and respectfully

express your concerns. Remember that sometimes, when someone is detached or numb, they may be in a lot of pain.

They may or may not be ready to open up to you. Keep an eye on them; they may benefit from extra support, even

if it is just casual conversation, going for a walk, or playing with puppies in the park. One of the greatest

gifts we can offer each other is compassion.

Solutions for the Listener (and the Storyteller)

Be prepared for people to tell you all kinds of things at any time, regardless of the setting, relationship, etc.

Even if you are caught off guard, told something graphic, or communicated with in a way that seems completely

off, there are some things you can do afterward to calm down.

After hearing or saying something upsetting, here are three proven strategies to help calm and relieve your body

and brain. My clinical recommendation is to practice these two to three times daily when you are not

feeling stressed. That way, it is easier for your brain and body to use these when you are stressed,

upset, or triggered. If it is hard for you to remember to do something like this, try setting a timer on your

phone or link it with something you already do two-to-three times a day, like when you brush your teeth or eat a

meal.

For bonus points, consider rating how you feel before and after practicing these. For example, on a scale of zero

to ten, where zero is neutral and ten is the highest level of distress you can imagine, how do you feel? (You

can think of it in terms of a specific emotion like anxiety, sadness, anger, or just generally speaking.)

1. Practice Grounding

This practice can help prevent upsetting thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks, and body sensations linked to adverse

experiences. Use your five senses to stay in or return to the present moment. Use sight, sound, touch, taste,

and smell to connect with what is happening around you right now.

- What do you see? I see my computer screen, clouds outside, and my favorite coffee mug.

- What do you hear? I hear the sound of my keys tapping on the keyboard.

- What do you feel (tactile/touch)? I feel the keys under my fingers.

- What do you taste? Yuck; I taste coffee brewed about six hours ago.

- What do you smell? Not a whole lot, but if I sniff my sleeve, I can smell detergent.

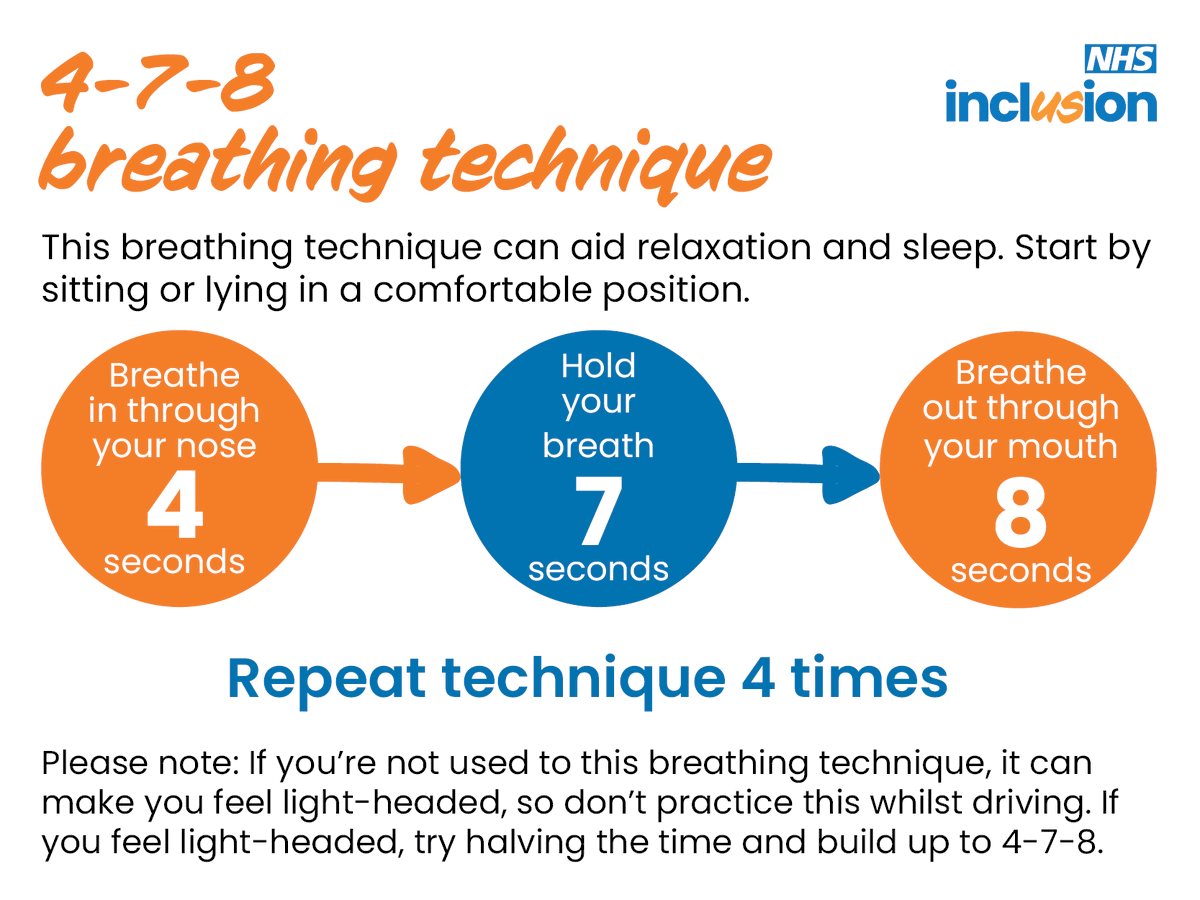

(Credit: Inclusion, UK National Health Service)

2. 4-7-8 (or Box) Breathing Technique

This technique was originally designed at Harvard University for students with test-taking anxiety. It was very

effective at lowering their anxiety and has since been taught and used in all kinds of settings. To correctly

practice deep breathing, when you inhale, your abdomen should expand outwards, and when you exhale, your belly

should contract inwards. Breathe from your belly, not your chest; otherwise, it is shallow breathing and can

lead to hyperventilation. If this is new for you, practice it sitting down for the first few times—you may not

be used to getting this much oxygen and I do not want you to get lightheaded!

(Credit: The Pragmatic Parent)

3. Peaceful Place Imagery

Now is the time for graphic, vivid, sensory details! Consider a place where you have been or want to go—real or

imaginary—that feels peaceful. Paint a sensory portrait of the place: What does it look like? What sounds do you

hear? What does it taste like? What do you feel there? Where are you in the scene? What time of year and day is

it? What does it smell like?

Consider adding anything that increases your sense of peace and comfort. Do you want cozy slippers? A cool or

warm beverage?

Lastly, how will you get there in your mind? Can you just close your eyes and imagine the place? Do you need to

imagine walking down a path or count to ten and you will be there?

The reality is that legal work (and life, for that matter!) is inherently stressful. There is no way to

completely avoid upsetting stories, content, and sometimes even trauma exposure, particularly in certain roles

and specialties. Best practices and evidence-based treatments can lessen the impact of the work and even help

individuals experience post-traumatic growth and compassion resilience.

Even if you do not work in military justice or a supervisory role,we all have a responsibility to create a

trauma-informed organization. As an organization, we have a responsibility to be trauma-informed in a way that

meaningfully acknowledges and supports everyone. Consider ways you can empower and be compassionate towards your

clients, colleagues, and yourselves. Take a “bite” of each communication skill and see what you like. Maybe you

will find you like them all, or they may take some getting used to. Think about ways you may be able to

incorporate these into everyday interactions, even if they feel a bit clumsy and awkward at first. With

practice, you will be better equipped to help yourself and others. TAL

Endnotes

1. Trauma-Informed Care, Trauma Pol’y, https://www.traumapolicy.org/topics/trauma-informed-care

(last visited Apr. 15, 2024).

2. Rebecca Howlett & Cynthia Sharp, The Legal Burnout Solution: Strategies for a Trauma-Informed Law

Practice, Am. Bar Ass’n (Oct. 26, 2021), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/gpsolo/publications/gpsolo_ereport/2021/october-2021/legal-burnout-solution-strategies-trauma-informed-law-practice.

3. Fast Facts: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention

[hereinafter Fast Facts], https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

(last visited Apr. 15, 2024).

4. Id.

5. Id.

6. Id.; VJ Felitti et al., Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading

Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) Study, 14 Am. J. Preventative Med. 245

(1998).

7. The Science of ACEs & Toxic Stress, Aces Aware, https://www.acesaware.org/ace-fundamentals/the-science-of-aces-toxic-stress

(last visited Apr. 15, 2024).

8. Fast Facts, supra note 3.

9. See Walter F. Baile et al., SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient

with Cancer, 5 Oncologist 302 (2000).

10. Lacie Parker, What Is ‘Comparative Suffering’—and Why Do HSPs So Often Get Stuck in It?, Highly Sensitive

Refuge (Feb. 23, 2022), https://highlysensitiverefuge.com/comparative-suffering.

11. Brené Brown, Rising Strong: The Reckoning. The Rumble. The Revolution. 8 (2015).

12. Id. at 8-9.

Ms. Pillsbury is the Wellness Program Director in the Office of The Judge Advocate General at the Pentagon.

Appendix: Resources

Department of Defense Mental Health Resources for Service Members and Their Families:

https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2737954/department-of-defense-mental-health-resources-for-service-members-and-their-fam

This Department of Defense website provides descriptions and links to various Department of Defense mental

health resources for Service members and their Families.

The National Center for PTSD’s Treatment Decision Aid:

https://www.ptsd.va.gov/apps/decisionaid

This online resource includes a decision aid on how to select a trauma treatment that best suits you. It’s

best to use this resource with a skilled therapist to create a tailored treatment plan.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing International Association (EMDRIA):

https://www.emdria.org/

This online resource offers a database to search for a therapist that specializes in EMDR, one of three

treatments that the Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs endorse for secondary and post-traumatic

stress.

Psychology Today:

https://www.psychologytoday.com

This online database allows users to search for a therapist with various filters, including accepted

insurance, types of problem, gender, specialty, etc.