From Native Guides to Commonwealth Defenders

Filipino Soldiers Under U.S. Command, 1899-1942

By Mark J. Reardon

Article published on: April 1, 2024 in the Army History Spring 2024 issue

Read Time: < 50 mins

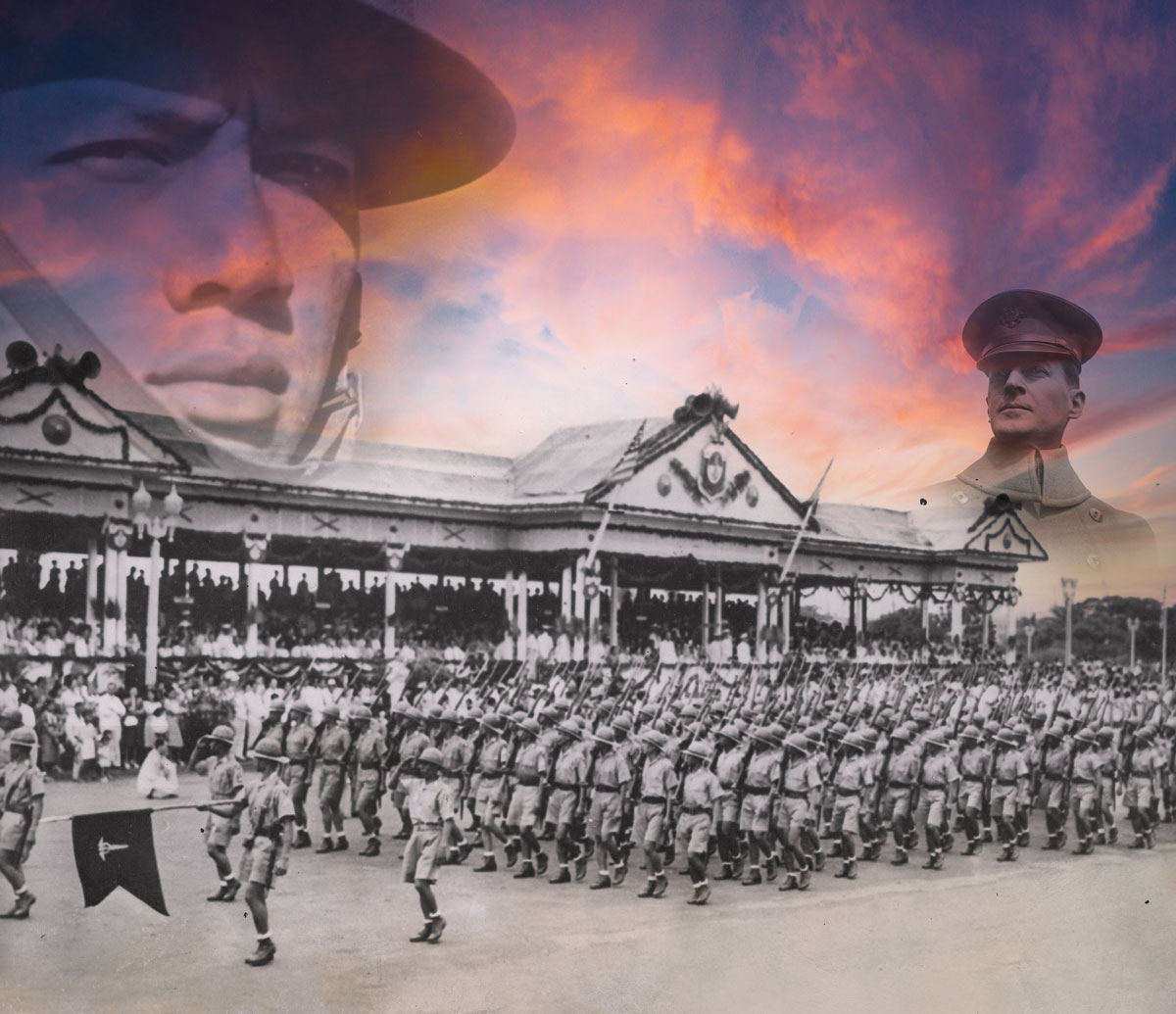

Filipino troops march in a military parade, ca. 1939. Courtesy of the Associated Press

The United States’ acquisition of the Philippines following the conclusion of the Spanish-American War in 1898 marked the beginning of the U.S. Army’s unique association with indigenous troops in the Pacific region. From 1899 to 1902, a revolutionary army of the Philippine Republic, under Emilio Aguinaldo, battled for independence against the American troops who had vanquished the Spanish garrison. This was the war of the Philippine Insurrection, which had begun after the United States had captured Manila on 4 February 1899. The conflict soon shifted from a conventional phase, in which Filipinos attempted to defeat U.S. troops in open battle, to a shadowy guerrilla war. The Americans experienced considerable delay and frustration as a result of that transition, prompting them to turn to Filipino allies as a means of preventing stalemate. That shift proved successful beyond all expectations, leading to a martial pairing of Americans and Filipinos that flourished through the end of the Second World War.

Securing Local Assistance During the Philippine Insurrection

Facing an unconventional war, the Americans possessed some knowledge of irregular warfare in a tropical environment, but they had not practiced it for more than fifty years, since the Second Seminole War in 1835–1842. Unfamiliarity with the terrain, much of which remained unmapped, compounded their acute lack of knowledge about the environment. Following the example of U.S. Army commanders in making use of the services of friendly Native Americans during the Indian Wars, U.S. forces gradually employed Filipinos from various tribes as guides, interpreters, boatmen, teamsters, and trackers. A letter from 1st Lt. Matthew A. Batson of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, dated 16 July 1899, provides the earliest official proposal to employ Filipinos as armed scouts. American soldiers, particularly mounted troops like Batson’s unit in northern Luzon, regularly experienced delays because of the numerous streams in the region. Batson wanted to solve that problem by using Filipino boatmen to build portable bridges. In his proposal, Lieutenant Batson suggested arming the native boatmen so they could protect themselves while performing that task.

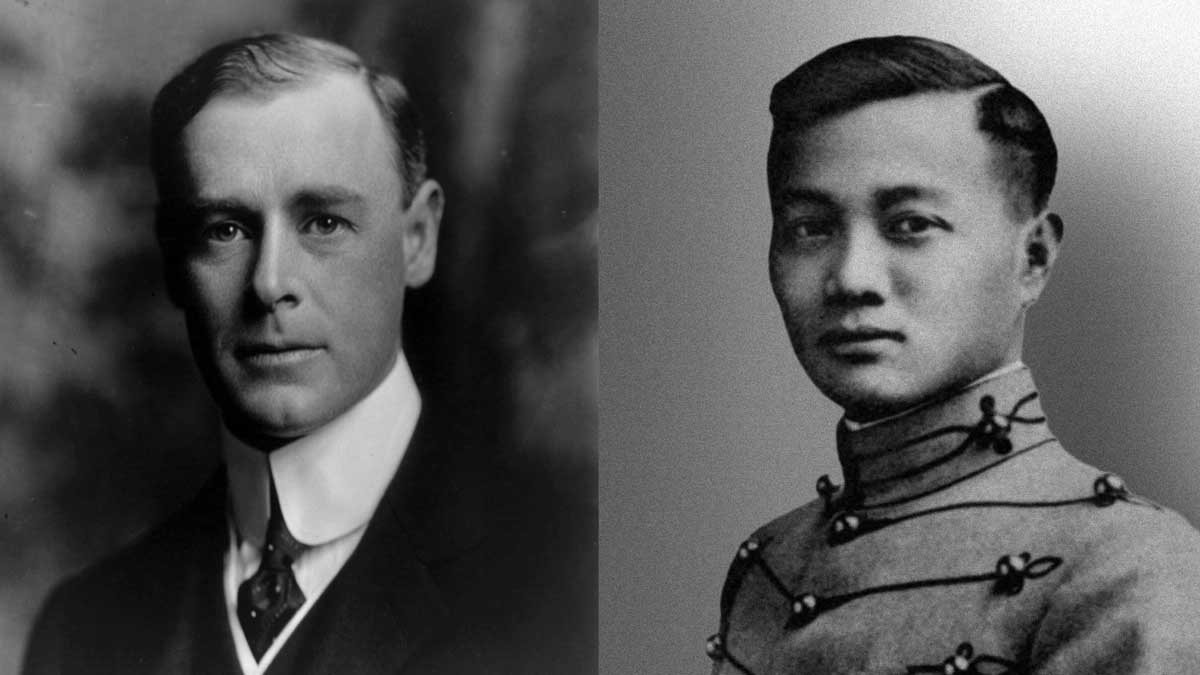

Left: Arthur MacArthur, shown here as a major general (National Archives) Right: Emilio Aguinaldo (Library of Congress)

Maj. Gen. Henry W. Lawton, commanding general of the VIII Corps’ 1st Division, accepted Batson’s proposition. In turn, Lawton requested War Department permission to form a company of one hundred armed Macabebe scouts. The Macabebe, whose prior service with the Spanish made them pariahs in the eyes of some Filipinos, were willing to serve under U.S. command. On 10 September 1899, Lieutenant Batson organized the first company of these volunteers, followed eleven days later by a second company and then three more companies in October. For accounting purposes, the scouts were paid as civilian employees of the Quartermaster Department and officered by personnel detached from the U.S. Army.

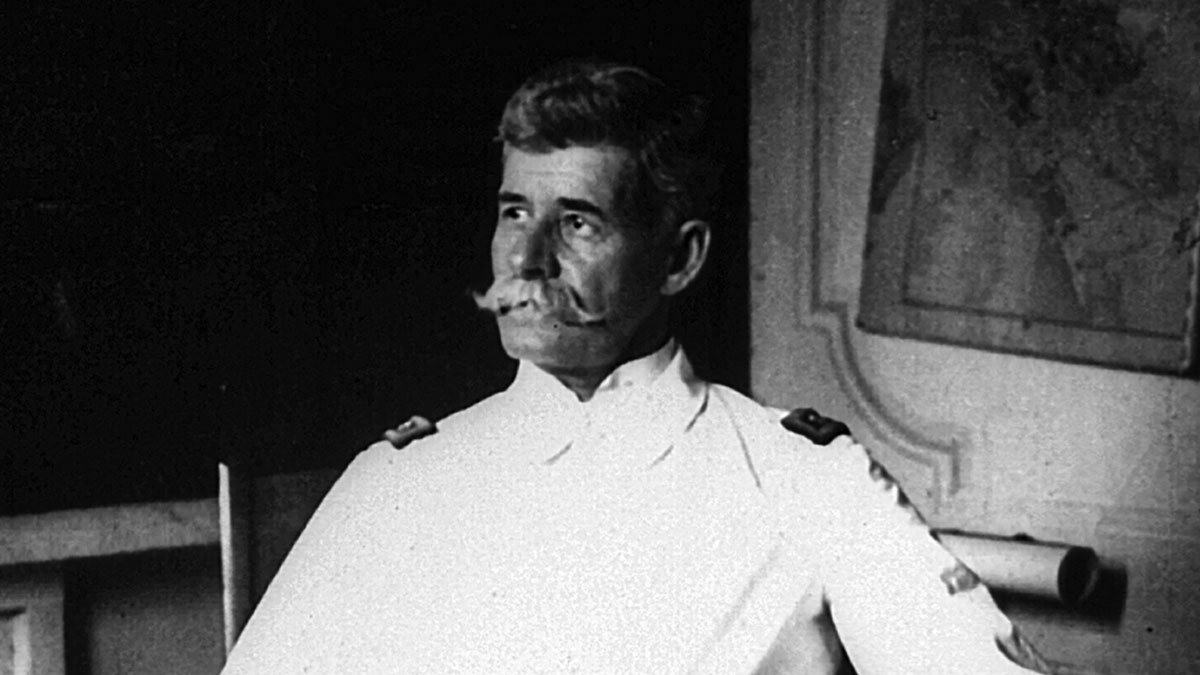

General Lawton at his headquarters in Manila, 1899 (Library of Congress)

The Macabebe scout companies soon proved their worth in combat. As a result, the U.S. Army decided that mounted patrols accompanied by native cavalry troopers could operate more efficiently than units made up exclusively of Americans. The expanding Filipino presence within the American military establishment mirrored developments taking place in the political, civil, law enforcement, and economic spheres of the Philippines. Rather than attempt to force a military solution on the Filipinos, the U.S. Army had adopted a pacification strategy designed to showcase the benefits of American rule.

On 3 April 1900, President William McKinley authorized the creation of a Filipino cavalry squadron. On 24 May 1900, Maj. Gen. Arthur MacArthur Jr., VIII Corps’ new commanding general and the Philippines’ military governor, approved the formation of a cavalry battalion of four troops of 120 soldiers each, engaged to serve until 30 June 1901 unless sooner discharged. Additionally, between May and December 1900, the Army formed a company of Ilocano native scouts in northern Luzon, spurring MacArthur to establish a fixed uniform rate of pay and allowances. He declared the scouts subject to military discipline, guaranteed them regular rations, and stipulated that pay and allowances would come from civil funds.

MacArthur also supported sending native scouts to southern Luzon to fight insurgents. In late January 1901, he authorized an additional battalion of Macabebe native scouts, a battalion of Cagayan native scouts, and a second company of Ilocano native scouts. The Army Reorganization Act of 2 February 1901 retroactively recognized the native scout initiative in the Philippines. In addition, the act promoted U.S. Army regular officers serving with scout units up to the rank of captain to the next highest grade and elevated sergeants to the rank of lieutenant. However, the act capped the number of Filipinos serving in the U.S. military at 12,000, which also counted toward the Army’s total enlisted strength.

Left: Governor-General Harrison (Library of Congress) Right: Vicente P. Lim, shown here as a West Point cadet (U.S. Military Academy Library)

The capture of Emilio Aguinaldo, the overall architect of the insurgency, by native scouts in March 1901 led to a significant decrease in violence. As a result, U.S. volunteer regiments began departing the Philippines in July 1901, leaving regular U.S. forces to assume all security responsibilities in the archipelago. Thoroughly convinced of the utility of indigenous troops, U.S. Army officials made up for the redeploying volunteers by retaining the services of a mounted scout battalion of four companies, ten companies of Lepanto native scouts, four companies of Cagayan native scouts, seven Macabebe companies, and seven Ilocano native scout companies. In addition, scout pay now came out of Regular Army funds and enlistment obligations were extended to three years.

World War I

After the insurgency, the American garrison in the Philippines refocused on a new mission. Following the defeat of Czarist troops in Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War (February 1904–September 1905), American military planners became convinced that Japan now posed the most dangerous threat to the Philippines. Manila Bay, a splendid 30-square-mile harbor on the shores of which sat the capital city and a seaport with excellent commercial infrastructure, was the most valuable prize for any potential invader. In case of invasion, the Philippine garrison would defend Luzon until reinforcements arrived from the continental United States.

In January 1905, the U.S. Army dropped ethnolinguistic identifiers from Filipino unit designations, adopting the generic term “Philippine scouts” instead. The name change, coupled with the decision to move widely dispersed companies that had been deployed in remote areas known for guerrilla activity to centrally located installations, marked the initial shift toward employing Filipino troops in conventional roles. The 2d, 3d, 4th, 5th, and 7th Battalions were organized in February 1905; followed by the 8th Battalion later that year; the 9th, 10th, and 11th Battalions in 1908; the 12th Battalion in 1909; and the 13th Battalion in 1914. The Philippine Constabulary, which took on the duties of an insular police force in October 1901, assumed primary responsibility for internal security in advance of this process.

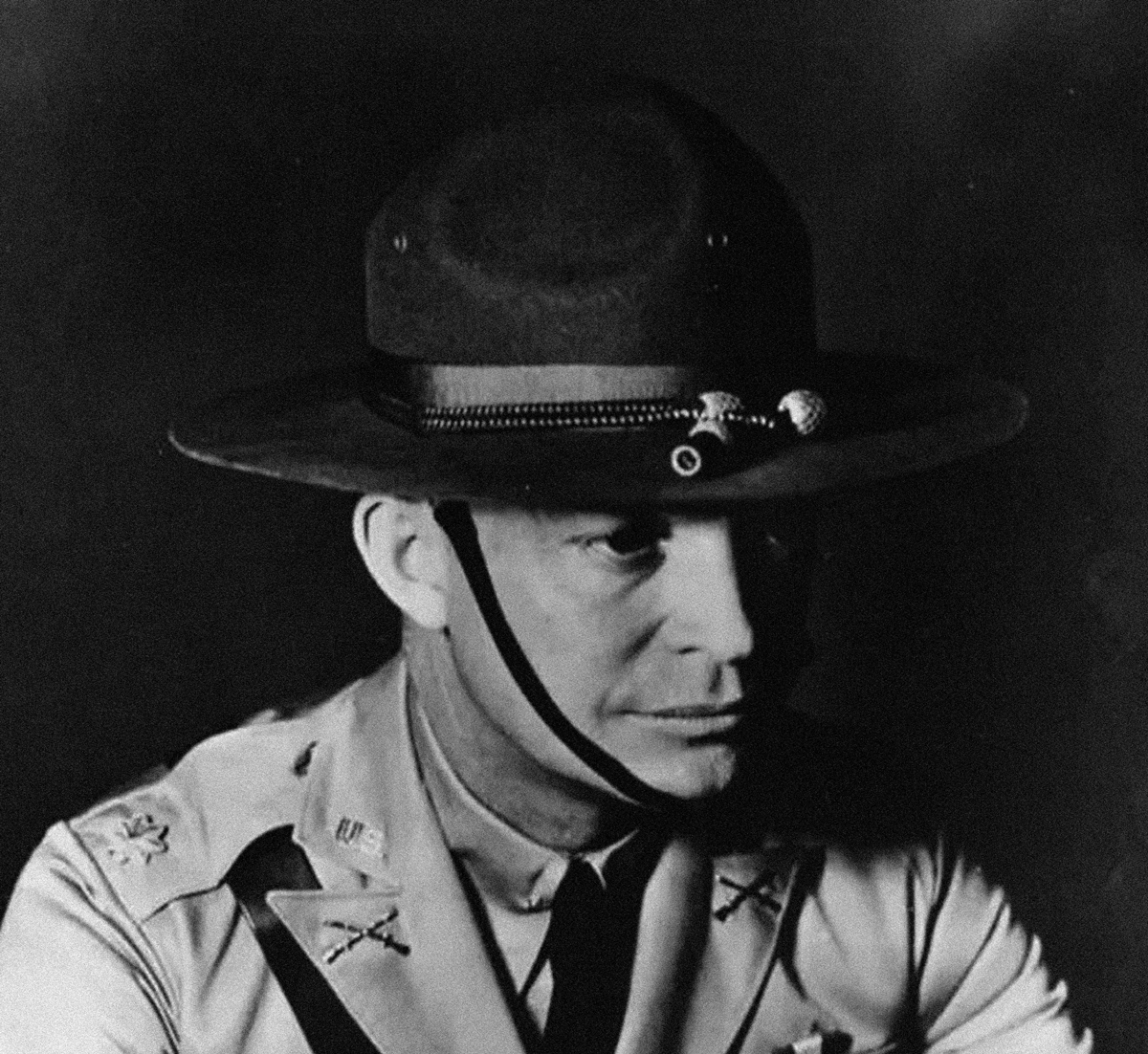

Douglas MacArthur, shown here as a brigadier general (Library of Congress)

A select few scouts were groomed for noncommissioned leadership roles as part of this latest reorganization initiative. Almost a decade passed before commissioned Filipino officers were allowed to serve in scout units. The first Filipino student to attend West Point, Vicente P. Lim, entered the academy in 1910. Two years later, 24-year-old Lt. Esteban B. Dalao became the first Filipino to be directly commissioned into the Philippine scouts. Over the next several years, Dalao was joined by fourteen more Filipinos, two of whom graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy and six of whom, including Lim, graduated from the U.S. Military Academy.

The American entry into World War I on 6 April 1917 accelerated the transformation of the scouts into a conventional force. Roughly 14,400 troops, of which 5,733 were Filipinos, were stationed in the archipelago when the United States joined the Allied powers. Within a few weeks, many continental soldiers were transferred from the Philippines to join units destined for service in France. By April 1918, the strength of the U.S. garrison in the Philippines fell to 9,300 soldiers. To offset the reduced number of U.S. personnel, President T. Woodrow Wilson authorized an additional four battalions and eighteen separate companies of Philippine scouts. The force structure increase resulted in the number of scouts growing to 314 (primarily U.S.) officers and 8,129 (predominately Filipino) enlisted personnel.

Major Eisenhower, ca. 1929 (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

Along with creating more scout units, the Army reorganized existing scout formations into four provisional infantry regiments, a field artillery regiment, a field signal battalion, and an engineer battalion. Twelve of the eighteen separate companies formed the headquarters, supply, and machine gun companies of the provisional infantry regiments. The remainder provided the headquarters and supply component for the artillery regiment and enlisted personnel for signal and engineer units. The reorganization marked a major milestone as the scouts began their transformation from a light infantry force to an all-arms organization with organic artillery, machine gun, engineer, and signal units.

The Philippine legislature played a part in archipelago’s defense for the first time on 12 April 1917 by authorizing the mustering of a National Guard division. The new organization consisted of three infantry regiments, a cavalry troop, two field artillery batteries, and two coast artillery companies. Within a few weeks, construction of training camps began as more than 25,000 Filipinos volunteered for military service. Not everyone was pleased with the initiative shown by politicians in Manila. When Governor-General Francis B. Harrison sought support for the project, the chief of the Militia Bureau in Washington, D.C., protested any reference to the unit as a National Guard organization because it was actually “a volunteer organization for war purposes.” The pushback led to Harrison referring to the organization thereafter as “the division of Philippine National Guard Volunteers.”

Despite lack of official sanction, officers from the garrison assisted the governor-general’s efforts to organize the new unit. In addition to filling critical staff functions, American troops trained 200 Filipino officer candidates and 100 prospective Filipino noncommissioned officers at a camp near Manila during late July through mid-September 1917. The lack of congressional approval prevented the U.S. Army from providing more assistance until the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a bill in late 1917 allowing Philippine volunteers to be federalized. The pace of training picked up as the division activated additional units in anticipation of movement orders that never came. Although the White House thereafter referred to the division as a National Guard formation, its administration remained the responsibility of the Philippine government rather than the Militia Bureau.

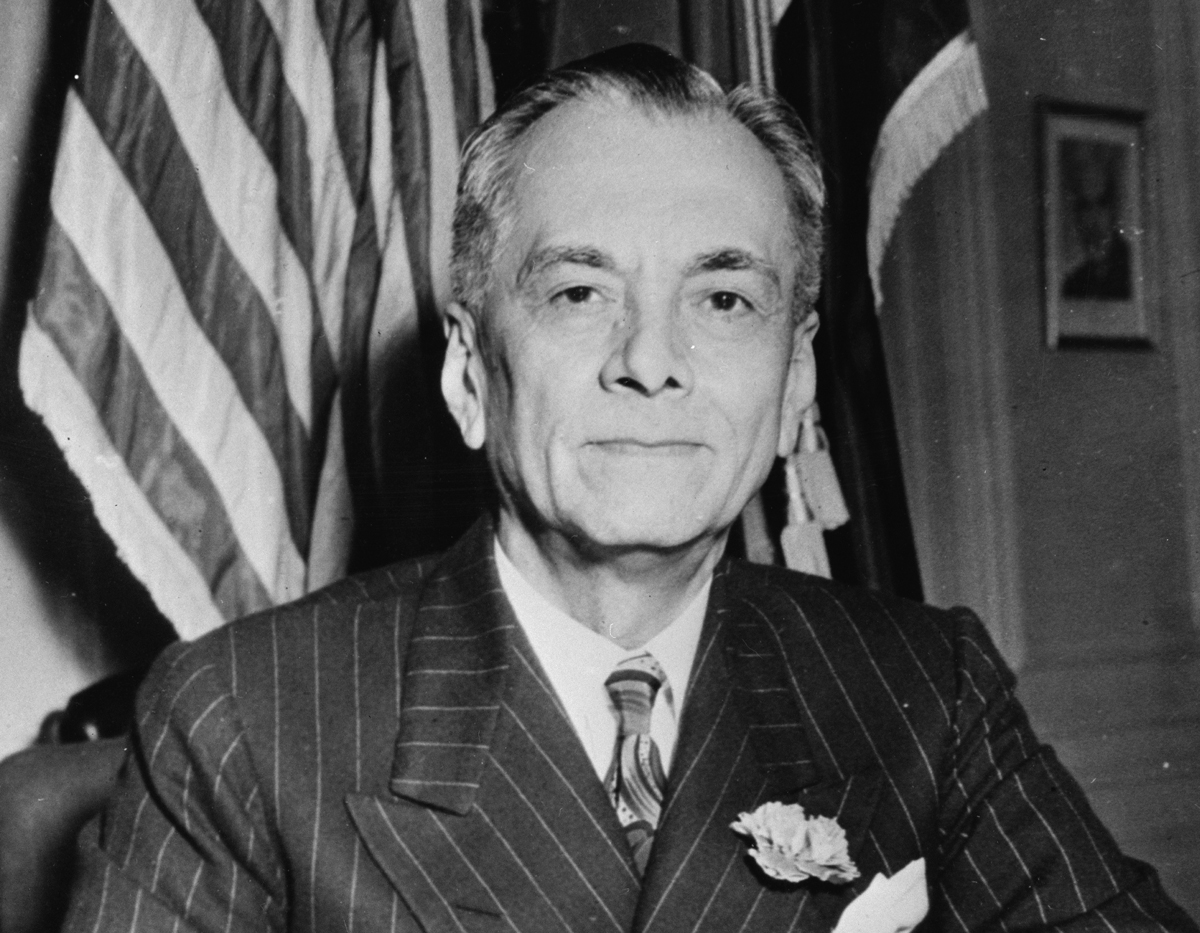

President Quezon (Library of Congress)

Nine days after hostilities ended in Europe on 11 November 1918, President Wilson called the Infantry Division, Philippine National Guard, into federal service for one month’s training. On 29 November, the War Department provided additional details when it notified the governor-general that the division would be called into service at reduced strength. The cessation of hostilities had resulted in the inactivation of the 3d Philippine Infantry Regiment and a separate signal unit. Meanwhile, in accordance with the president’s proclamation, the division of Philippine National Guard Volunteers already had begun assembling. Although the division mustered out on 19 December 1918, its members continued training for two more months before the unit formally disbanded.

Reorganizing the Scouts

The Army revisited the postwar status of the Philippine scouts while it prepared to dissolve the division of Philippine National Guard Volunteers. The War Department wanted the ability to expand rapidly in the event of a future conflict by mandating universal military training for all male U.S. citizens. That proposal gained little traction within legislative circles as evidenced by the National Defense Act of 4 June 1920. The act created the Army of the United States, consisting of the Regular Army, the National Guard, and the Organized Reserves, but it failed to mandate universal military training. It also set the peacetime end strength of the Regular Army between 170,000 and 280,000 and authorized 435,800 soldiers for the National Guard. However, legislators then appropriated sufficient funds for a Regular Army numbering 200,000 officers and enlisted soldiers with no further increase in sight. Indeed, a growing aversion to defense spending ensured that this figure fell by another 50,000 by 1921.

The 1st Division, Philippine Commonwealth Army, on parade at Camp Murphy, 13 November 1939 (Courtesy of Dr. Ricardo Trota Jose)

The National Defense Act of 1920 posed a major administrative challenge because the scouts were not regulars, national guard soldiers, or reservists. As a result, the War Department settled on integrating them with the Regular Army by transferring the colors of four stateside infantry regiments that had been slated for inactivation to the scouts. At the time, a standard U.S. infantry division consisted of two brigades with two regiments apiece and an artillery brigade plus supporting troops. The colors of the 43d, 45th, 57th, and 62d U.S. Infantry Regiments were sent to the Philippines, accompanied by a cadre of officers from each unit.

The officers and colors of the incoming units disembarked at Manila on 3 December 1920. With the stroke of a pen, the 1st Philippine Infantry Regiment (Provisional) became the 45th Infantry Regiment (Philippine Scouts [PS]), and the 2d Philippine Infantry Regiment (Provisional) transformed into the 57th Infantry Regiment (PS). In January 1921, the U.S. Philippine Department formed the 62d Infantry Regiment (PS) using personnel from the 4th Philippine Infantry Regiment (Provisional). Two months later, elements of the 2d, 8th, and 13th Battalions respectively became the 1st, 2d, and 3d Battalions of the 43d Infantry Regiment (PS).

Though the Philippine garrison now had a division-sized complement of infantry, it still lacked several artillery battalions, signal elements, and a medical unit. In May 1921, the War Department redesignated the 1st Philippine Field Artillery (Mountain) as the 25th Field Artillery (PS). That same month, the provisional Philippine engineer units were formed into the 1st Battalion, 14th Engineers (PS). The Philippine Division, consisting of a mix of U.S. and scout units, was then activated at Fort William McKinley, Taguig City, Philippines, on 8 June 1921. The Philippine Department added a Philippine scout brigade headquarters, the 23d Brigade (PS), to its table of organization in 1922, followed by a second brigade headquarters, the 24th Brigade (PS), in 1931.

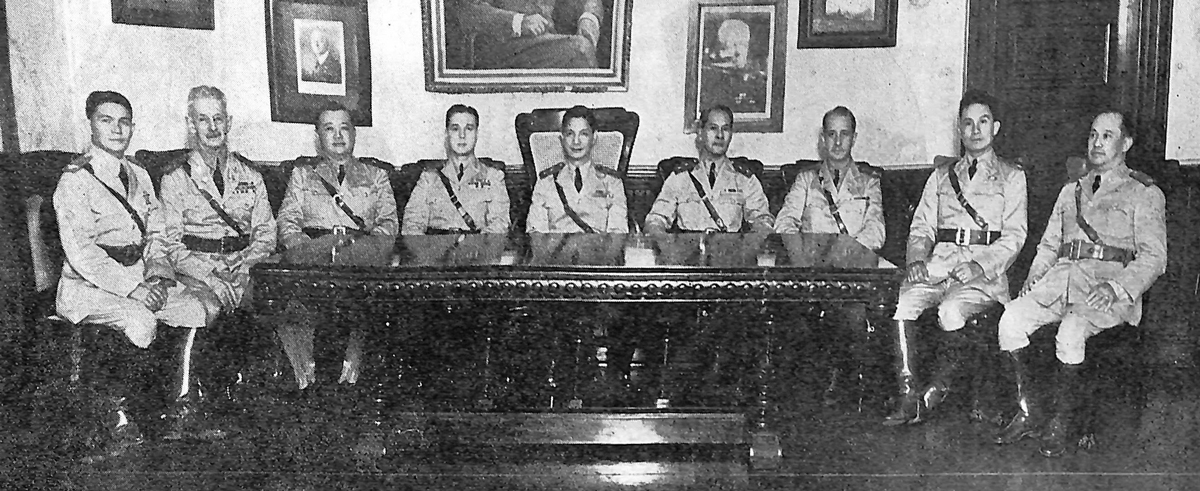

The Philippine Commonwealth Army’s Central General Staff (left to right): Col. Rafael L. Garcia, Col. Charles E. Livingston, Brig. Gen. Vicente P. Lim, Maj. Gen. Basilio J. Valdes, Maj. Gen. Paulino T. Santos, Maj. Gen. Jose de los Reyes, Col. W. E. Dosser, Col. Fidel V. Segundo, and Lt. Col. Victoriano Luna, ca. 1939 (Courtesy of the Presidential Museum and Library, Republic of the Philippines)

Postwar downsizing arrived in the Philippines with a vengeance once Congress cut the Army’s overall strength to 125,000 personnel. As a result, the strength of the Philippine garrison fell from 19,525 to 11,656 between 1921 and 1922. Both the 43d and 62d Infantry Regiments (PS) were inactivated. The former retained a cadre in accordance with a War Department directive designating it as an “active associate” of the 45th Infantry. The same orders authorized the formation of the 12th Ordnance Company (PS). In addition, the 12th Medical Regiment, a Regular Army formation, re-formed as a Philippine scout unit several months before the inactivation of the infantry regiments.

In September 1922, the War Department authorized the creation of the 26th Cavalry (PS) using 701 enlisted soldiers from the 25th Field Artillery (PS). The 26th Cavalry took over the animals and the equipment of the departing 9th U.S. Cavalry. Some of the continental officers from the 9th Cavalry, reassigned to the new regiment, also remained in the Philippines. Using personnel and equipment siphoned from coast artillery companies formed during World War I, the Philippine Department formed the 91st and 92d Coast Artillery Battalions (PS) on 30 June and 1 July 1924, respectively.

The only incident marring the otherwise exemplary record of the Philippine scouts occurred in July 1924. On the evening of 27 June, a scout secretly had visited the quarters of the Fort McKinley provost marshal to inform him that his comrades were organizing a large-scale protest against their unequal pay and status in comparison to U.S. soldiers. A U.S. Army private, for example, received thirty dollars a month while a Philippine scout of the same rank earned only ten dollars. A quick investigation disclosed that discontent among the scouts had grown to alarming proportions after units from outlying locations were congregated at Fort McKinley (near Manila) and at Fort Stotsenberg, located 55 miles north of the Philippine capital. The provost marshal acted on the tip a little more than a week later by arresting twenty-two scouts during a raid on a clandestine meeting.

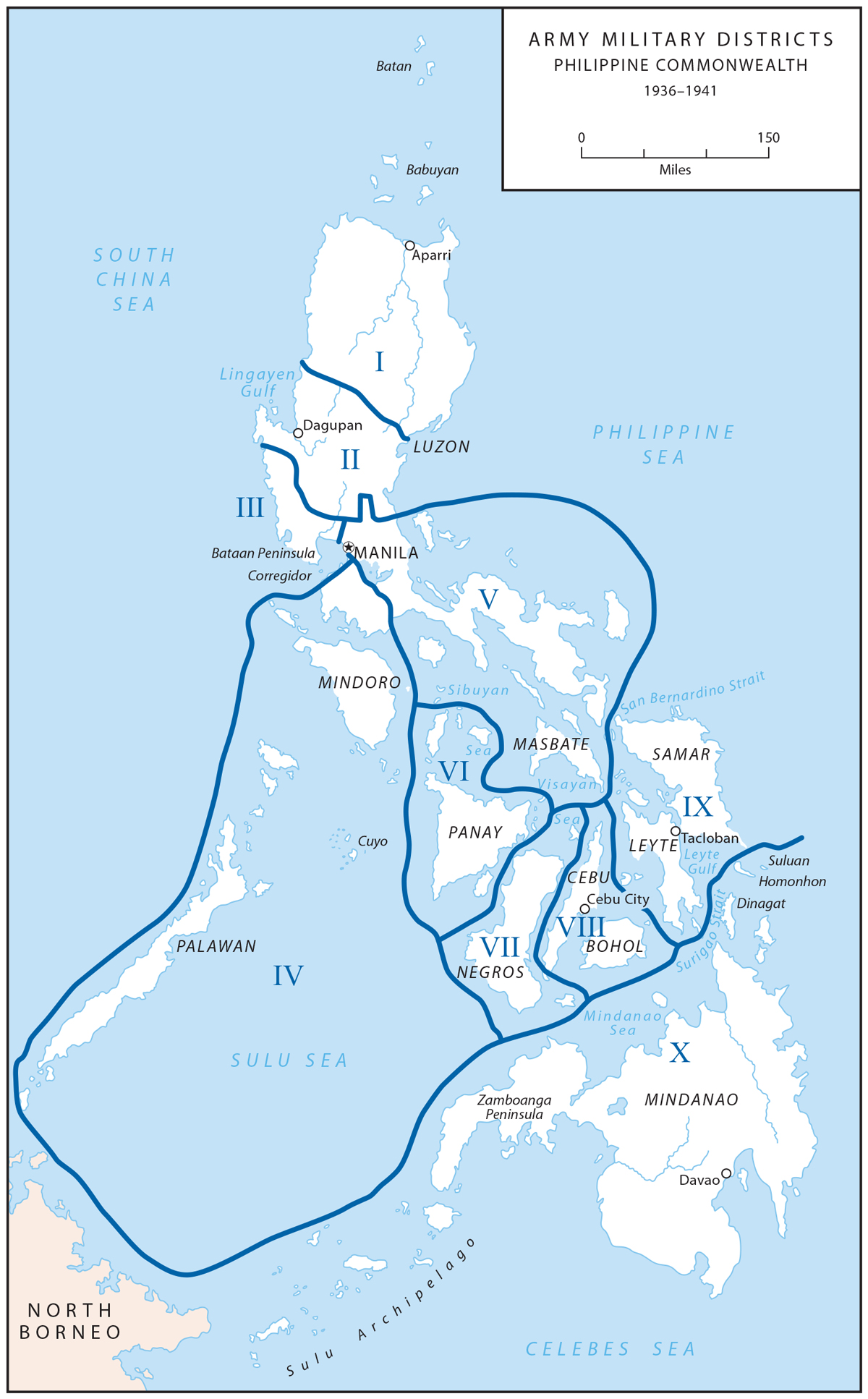

Map 1

On 7 July, officers from Col. Douglas A. MacArthur’s 23d Infantry Brigade (PS) were dismayed to find that 380 members of the 57th Infantry had refused to report for duty. On 8 July, more than 220 members of the 12th Medical Regiment (PS) followed suit. The mutiny collapsed later that day, after the officers in both units confronted the insubordinate scouts. Almost 400 scouts returned to duty without further incident while the military police transported the remaining 200 to the stockade.

The War Department allowed local military authorities to handle the matter as they saw fit. In late July and August 1924, 209 scouts were tried on charges of mutiny and unbecoming conduct. One-hundred-and-three scouts were found guilty of mutiny and ordered to be dishonorably discharged, forfeit all pay and allowances, and serve up to five years in prison. Six of the scouts were acquitted. An appeals court halved the sentences, and with time off for good behavior, most of the prisoners were released within two years. Afterward, the Philippine Department took the precaution of inserting undercover security agents into scout companies for the next several years.

The mutiny fed lingering concerns among War Department officials about the loyalty of indigenous Filipino soldiers. Their unease resulted in some hesitation about upgrading small arms issued to Filipinos, and they tightened controls over larger weapons such as field artillery. On a positive note, the War Department motorized scout artillery units during the mid-1920s, seeking to improve the garrison’s ability to respond to the threat of amphibious invasion. The Philippine Division also enjoyed a major advantage over its stateside counterparts in that it conducted large-scale training maneuvers each year.

Filipino soldiers training with an M1917 75-mm. field gun (National Archives)

Even though issues with pay and the desire for independence lingered beneath the surface following the 1924 mutiny, American officers still felt the scouts were well-trained, superb soldiers. Most enlisted scouts had served in their units for many years and knew their jobs thoroughly. Their living conditions and health benefits were better than those of the average civilian. Company first sergeants functioned as unit recruiting officers. They often selected new recruits from their own provinces or from other tribes who spoke the same dialect. It was not uncommon for the son of a scout to join his father as a member of the same unit.

With the constabulary responsible for maintaining law and order, the Philippine scouts concentrated on honing their professional skills in anticipation of a possible confrontation with the invading forces of a hostile nation. However, combat readiness suffered because the understrength scout units could not conduct realistic training. Each of the infantry regiments lacked a third battalion as well as supporting units such as their antitank and cannon companies. The coast artillery units had only two battalions instead of three. Personnel shortfalls prevented scout units from training under simulated wartime conditions. The coast artillery battalions, for example, worked around personnel shortages by performing each task on a rotating basis.

Building the Philippine Commonwealth Army

In March 1934, the U.S. Congress passed legislation setting the prerequisites for the archipelago’s independence in 1946. On 24 March, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which granted full independence ten years after the Filipinos drafted a constitution, elected a representative government, and chose a national leader. The legislation allowed the United States to maintain its military presence in the Philippines during the transition period and also permitted the United States to call the armed forces of the Philippine Commonwealth into U.S. service before the archipelago gained its independence. A group of Filipino lobbyists who had been staying in Washington, D.C., conveyed the act to Manila, where the legislature approved it on 1 May 1934.

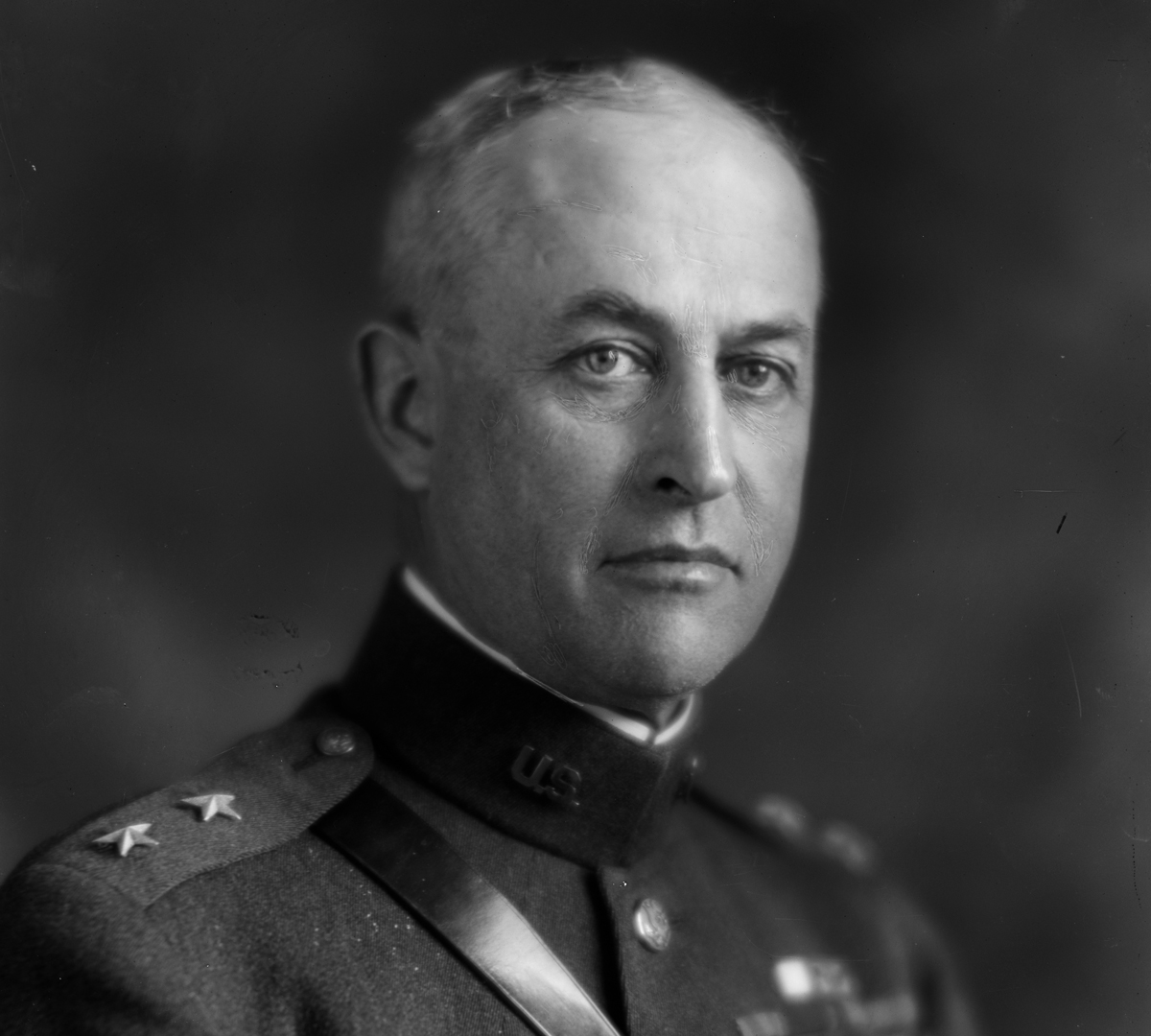

Malin Craig, shown here as a major general (Library of Congress)

In accordance with the terms of the act, Filipinos elected delegates for a constitutional convention on 10 July. In the process of drafting the constitution, Filipino politicians seeking to solidify the archipelago’s pending claim to sovereignty proposed the creation of a military force separate from the scouts and the constabulary. The ensuing debate over national defense questions proved to be a lengthy one, as many legislators, for a variety of economic and political reasons, long had opposed the forming of a Filipino military force.

While legislators wrangled over the proposed constitution, Philippine Senate leader Manuel L. Quezon traveled to Washington, D.C., to seek input on defense matters from several prominent Americans, including now Lt. Gen. Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur had risen in rank since leaving the Philippines and now served as the Army’s chief of staff. Quezon asked the general if he would be willing to oversee the creation of the Philippine military. With his tour as chief of staff due to end the following year, MacArthur agreed to Quezon’s request, provided that President Roosevelt and Secretary of War George H. Dern approved.

In anticipation of Roosevelt’s and Dern’s approval, MacArthur directed the Army War College to put together a plan for a Philippine Commonwealth military force on 1 November 1934. A select group, headed by Maj. James B. Ord, worked out a draft concept, which they forwarded to MacArthur’s office. Maj. Dwight D. Eisenhower, serving on MacArthur’s staff, reviewed the draft, which had been prepared on the optimistic assumption that there would be no fiscal or personnel constraints. Before sharing the plan with MacArthur, Eisenhower and Ord reduced the project’s annual budget to $11 million. The revised version called for a large army of reserve divisions, formed around a core of 20,500 full-time Filipino regulars, along with smaller air and naval components. When MacArthur reviewed their work, he told Eisenhower and Ord to reduce the annual expenditures by another $3 million. To meet this revised ceiling, they reduced the regular component to 7,930 personnel, downsized ammunition stockpiles, and authorized fewer heavy weapons, particularly artillery pieces.

On 14 May 1935, Congress approved a bill adding the Philippines to the list of countries eligible to receive a U.S. military mission. On that same day, the Philippine people approved their new constitution in a national referendum. Upon its ratification, the U.S. governor-general issued a proclamation calling for national elections that fall. On 17 September 1935, Filipinos elected Manuel Quezon as their president and Sergio Osmeña as their vice president. Foreign affairs, defense, and monetary matters remained under U.S. oversight until 1946, but Filipinos now handled all other political matters.

On 18 September, Secretary Dern issued Special Orders No. 22, detailing General MacArthur to assist the commonwealth with military and naval matters. Although MacArthur remained on active duty after stepping down from the position of chief of staff, he reverted to his permanent rank of major general. Majors Eisenhower and Ord accompanied him as members of what had become known as the Philippine Military Mission. Soon after arriving in Manila in late October, MacArthur presented Quezon with the plan developed by Ord and Eisenhower.

Acknowledging the impracticality of building a navy strong enough to interfere with an enemy invasion fleet or maintain interisland communications during wartime, the plan centered on deterring potential aggressors by deploying a sizable infantry force on each major island. Because the plan depended on the simultaneous mobilization of all ground forces while conceding control of the surrounding waters to an invader, it required a decentralized means of mobilizing, training, and sustaining Philippine defensive efforts. As a result, MacArthur proposed the creation of ten military districts, each responsible for raising three reserve infantry divisions of 10,000 soldiers each, that would encompass the entire archipelago. (See Map 1.)

Left: A cadet poses with a rifle at the Philippine Military Academy, Baguio, Philippines, c. 1937 (Courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Libraries) Right: George Grunert, shown here as a lieutenant general (U.S. Army)

Divided into three equal phases, each lasting ten years, the plan would begin on 1 January 1937 and be completed on 1 January 1967. The initial phase called for fielding a small regular component, ten 10,000-person reserve infantry divisions, a composite aviation battalion, and four coastal navy flotillas with sixty motor torpedo boats. Ten additional reserve divisions were slated to be fielded during the second phase, which also focused on building up equipment stockpiles. The final tranche of units required to reach the ultimate goal of thirty reserve divisions would be created during the third phase.

Quezon publicly introduced MacArthur’s plan to the Philippine legislature on 22 November 1935. A series of conferences preceded the announcement to allow legislators to work out the legal details required to implement it. The Philippine Commonwealth Army formally came into being with the passage of Commonwealth Act No. 1 on 21 December 1935. The legislation created the General Staff Corps and established the Philippine military’s medical, legal, finance, quartermaster, ordnance, and chaplain services. A military school, designated as the Philippine Military Academy, was established for selected candidates seeking permanent commissions in the Philippines’ regular army. The act provided for a regular component consisting of infantry, artillery, cavalry, aviation, and naval branches. It also authorized the creation of a reserve force made up of “any number of Infantry Divisions” as well as additional aviation and naval elements.

Filipinos enlist in the U.S. Army at Fort McKinley in March 1941. (Author’s Collection)

The Council of National Defense, consisting of Quezon, Osmeña, the head of each executive department, the Philippine Commonwealth Army’s chief of staff, and six others designated by the Philippine president, stood at the pinnacle of the commonwealth’s embryonic military hierarchy. The Philippine Commonwealth Army’s chief of staff also served as the head of the Central General Staff. Modeled after its U.S. Army counterpart, the Central General Staff consisted of the chief of staff, a deputy chief of staff, and officers in the rank of third lieutenant or higher. The Central General Staff had the responsibility of preparing plans for national defense and mobilization, evaluating unit readiness, conducting inspections, ensuring training standards, and assisting the infantry, cavalry, and artillery branches, as well as the Air Corps and Offshore Patrol (Navy) as needed.

On 11 January 1936, President Quezon made the first appointments in the Philippine Commonwealth Army officer corps. As might be expected, Quezon preferred candidates with experience in the constabulary or Philippine scouts. He chose retired Brig. Gen. Jose de los Reyes, the senior member of the constabulary, as the chief of staff. Quezon then appointed Brig. Gen. Basilio J. Valdes, also of the constabulary, as the deputy chief of staff while Col. Guillermo B. Francisco became the assistant chief of staff. However, de los Reyes soon ran afoul of Quezon when he began announcing officer appointments before clearing them with the president. In addition to the growing gulf between Quezon and de los Reyes, it soon emerged that many constabulary officers were professionally ill-prepared for the challenge of creating a thirty-division army, air corps, and offshore patrol from scratch.

These issues faded in May 1936 when the Central General Staff underwent a major reorganization that resulted in the reassignment of de los Reyes as provost marshal general. Constabulary Col. Paulino T. Santos received a promotion to major general when he stepped into de los Reyes’s vacated slot as chief of staff. General Valdes was elevated to the same rank after being appointed as Santos’s deputy. Colonel Francisco, newly promoted to brigadier general, took command of the sole regular division. The assistant chief of staff’s responsibilities were now divided amongst three billets: Col. Vicente P. Lim became assistant chief of staff for war plans; Lt. Col. Fidel V. Segundo drew the assignment of assistant chief of staff for intelligence, operations, and training; and Col. Rafael L. Garcia assumed the post of assistant chief of staff for personnel and supply.

Equipping the Philippine Commonwealth Army

The core tactical elements of the Philippine Commonwealth Army were designed as light infantry divisions with “equipment and armament suitable to the economy and terrain,” consisting of 10,080 troops (compared to 15,200 in a U.S. Army infantry division). Each division theoretically possessed three infantry regiments, a cavalry squadron, an engineer battalion, an artillery regiment, a transportation battalion, a communications company, and a division headquarters. In addition, each division possessed an organic reserve of 2,400 personnel. Rather than depend on replacements from outside the military district, Filipino division commanders could recoup battle losses using soldiers already assigned to their units.

Filipino troops take part in a Philippine Scout competition. (Author’s Collection)

Philippine Commonwealth divisions were authorized eighteen 81-mm. and twenty-four 120-mm. Brandt mortars rather than the thirty-six 75-mm. cannons, eight 105-mm. howitzers, and eight 155-mm. howitzers allocated to U.S. divisional artillery contingents. Lower per weapon cost, ease of operation, and smaller unit frontages provided the rationale for equipping Philippine divisions with mortars. A planned battalion of twelve .50-caliber machine guns, intended for Filipino artillery regiments, would provide divisions with antitank and antiaircraft capabilities. Other weapons allotted to Philippine reserve divisions included 6,900 rifles, 492 pistols, 431 Browning automatic rifles, and 54 .30-caliber water-cooled heavy machine guns.

Concerns about cost overruns resulted in the Philippine regular army initially absorbing most of the constabulary rather than bringing on new recruits. Although the constabulary already possessed rifles, submachine guns, and shotguns, it did not have any artillery or surplus small arms. Moreover, the mass transfer of personnel consumed most of the regular personnel spaces, leaving only 300 officers and 3,000 enlisted personnel available to fill the 2,490 authorizations in 1st Division, 900 army training billets, 419 air force positions, and 420 navy slots.

The challenge of equipping the initial group of ten reserve divisions loomed large. Weapons acquisition had to account for the cost of both purchase and upkeep. Balking at the hefty eighty-five-dollar price of M1903 Springfield rifles, the United States’ Philippine Military Mission sought to procure 360,000 M1917 Enfield rifles from U.S. stocks at nine dollars apiece. The Philippine Commonwealth Army also borrowed weapons, such as Browning automatic rifles and .30-caliber machine guns, from the U.S. Philippine Department for training purposes. Although the Philippine government did not have to pay for their use, it did have to purchase ammunition for them. Compounding the equipment problems, U.S. depots did not contain any Brandt mortars, which were essential to arming the Filipino artillery regiments.

Generals Wainwright (left) and Douglas MacArthur (Library of Congress)

Other problems emerged when the outbreak of war in Spain and China drove up global arms prices. As a result, Eisenhower discarded plans to procure 120-mm. mortars in favor of obtaining surplus 75-mm. field guns from stateside U.S. Army depots. As a further cost savings, he also cut the number of .50-caliber machine guns for each division. Confronted with a mushrooming defense budget that threatened to make a mockery of the estimate provided to Quezon, General MacArthur asked the War Department to send obsolete Lewis machine guns, Stokes mortars, and 75-mm. field guns to the Philippines. Although the War Department agreed to provide the surplus weapons, it did so only on the condition that American inspectors would have free access to commonwealth armories. Ammunition for the 75-mm. cannons had to be stored at U.S. Army depots on the island of Corregidor in Manila Bay.

Although the procurement of weapons and ammunition remained a thorny issue, the nascent Commonwealth Army’s development undertook a major step forward in 1937 when it formed ten military districts, each with a division headquarters assigned. Luzon, together with several outlying islands (Mindoro, Palawan, and Masbate), accounted for five military districts; Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago combined to constitute a sixth district; and the Visayas (Cebu and other centrally located islands) made up the other four districts. Each military district had responsibility for peacetime training, administration, the distribution of supplies, and maintenance of equipment. MacArthur planned for each district to raise one reserve division by 1940, with an ultimate goal of three divisions per district.

Training the Philippine Commonwealth Army

In August 1937, Lt. Gen. Malin D. Craig, the U.S. Army chief of staff, sent a radiogram to the Philippine Military Mission directing General MacArthur to return to the United States in October. A surprised MacArthur applied for retirement rather than assume a final stateside posting. General Craig approved MacArthur’s request, setting 31 December 1937 as his last day on active duty. From that date forward, requests from the Philippine government for additional personnel, materiel, or services would be transmitted to the War Department through the commanding general of the Philippine Department. Although MacArthur no longer had direct access to the U.S. military decision-making apparatus, Quezon allowed him to continue serving as the commonwealth’s chief military adviser.

With Japanese troops driving deeper into China, and Germany proclaiming its intentions to acquire Czechoslovakia and Austria, MacArthur finally convinced President Quezon of the need to increase annual military expenditures. The additional funds would be used to construct warehouses and mobilization centers and to make improvements to much of the existing infrastructure. Although the request met with legislative approval, the increase was confined to one budget session. Meanwhile, the looming possibility of a broader conflict in Asia led to increasingly strained relations between Quezon and MacArthur. Quezon had pressed ardently for independence earlier than 1946 until the threat of war convinced him that the Philippines would be better off remaining as a U.S. possession for the foreseeable future. He therefore viewed MacArthur’s continued presence as a costly detriment. Quezon covertly sought to obtain MacArthur’s resignation by undercutting his authority and reducing defense expenditures.

Although the Philippine Commonwealth Army made significant progress toward the initial goal of creating ten reserve divisions in little more than two years, the five and a half months of training for mobilized reservists often included nonmilitary subjects such as basic sanitation and learning how to read and write. As a result, the reservists did not have time to master their military duties sufficiently enough to remember them when called back for refresher training. In addition, field maneuvers for reservists were impractical because the 120 mobilization and training centers, each hosting only 150 to 200 trainees, were scattered across more than twenty islands. This meant that Philippine Commonwealth Army officers rarely had the opportunity to lead more than a company of troops.

In January 1938, 20,000 Filipino reservists from the 2d, 3d, and 4th Military Districts joined 10,000 U.S. Army personnel for two weeks of military maneuvers. Although the combined maneuvers garnered much positive publicity, they revealed major problems within the Philippine Commonwealth Army’s sole regular unit. Though the constabulary officers had considerable law enforcement experience, they knew little of basic military skills such as map reading and field fortifications. Classes were offered to senior officers, but many refused to learn from instructors with lesser rank. These developments, along with the discovery that police officers did not always make good soldiers, contributed to the 23 June 1938 decision to restore the constabulary to a purely law enforcement role. Efforts to reconstitute the sole Philippine Commonwealth Army regular division encountered predictable fiscal and staffing challenges, with the result that it rematerialized as a single, skeletonized, infantry regiment, lacking artillery and support troops.

A Philippine Commonwealth Army board that had been created to evaluate the ongoing defense buildup subsequently recommended curtailing reserve training in favor of fielding two regular infantry divisions. The board advocated investing the money that would be saved by mobilizing fewer enlisted personnel each year in training more officers. Acting on advice proffered by Vicente Lim, now a general, Quezon approved the recommendation to train fewer reservists while devoting more effort to cultivating a professional officer corps. Quezon later made his thoughts clear, when he asked Major Eisenhower, “[W]hy did we plunge into the mass training of enlisted reservists before we had the officers, at a time when we knew that we did not have them, to do the job with reasonable efficiency?”

In his ongoing effort to reduce MacArthur’s influence, Quezon persuaded the National Assembly in May 1939 to establish the Department of National Defense, headed by Teofilo Sison. Sison immediately forbade the Philippine Commonwealth Army from ordering ammunition, negotiating construction contracts, or recruiting new personnel without seeking his department’s approval. The military mission also began working through the Department of National Defense rather than directly interacting with Quezon’s office. The president began diverting funds from the Philippine Commonwealth Army to the constabulary in response to internal security issues created by severe labor unrest and political instability. He then publicly questioned the need for a large Filipino military. In a speech at the Philippine Normal School, Quezon told attendees that he did not think the Philippines could be defended even if every Filipino was armed. Quezon repeated that statement a week later when addressing members of the University of the Philippines College of Law.

In June 1940, the commonwealth’s Central General Staff underwent another reorganization that reflected the lessons learned during the past three years. Two of the three assistant chiefs of staff took on new responsibilities, with the first assistant chief of staff adding reserve unit employment to his oversight of war plans, and the third assistant chief of staff changing from personnel and supply to supply and industrial preparedness. Personnel matters, which had been under the purview of the third assistant chief of staff, transferred to the new position of fourth assistant chief of staff. A fifth assistant chief of staff was created to oversee fiscal matters. Colonels Lim, Segundo, and Garcia retained their positions as the first, second, and third chiefs of staff, respectively. Lt. Col. Irineo Buenconsejo became the fourth assistant chief of staff, and Capt. Amadeo Magtoto was the fifth assistant chief of staff.

During this same period, the American military mission’s initial efforts to obtain more equipment and supplies from the United States met with scant success. The logjam broke in August 1939 when the War Department promised to send additional weapons from American depots to the Philippines. Planned to be spread across a three-year period, these shipments would consist of 110 3-inch mortars in 1940, followed by 54 more in both 1941 and 1942; 166 Browning automatic rifles in 1942, but none in 1940 or 1941; 60 .30-caliber machine guns in 1940, with 240 more in both 1941 and 1942; and 20 3-inch guns in 1940, followed by 24 more in 1941 and 1942. The additional weapons created a significant increase in firepower, but the majority of the indirect fire systems were obsolete and due to be replaced by newer models.

War Plan Orange

Promises of additional weapons coincided with increasing American interest in making use of commonwealth military forces. The prohibitive cost of maintaining a large garrison in the Philippines had always limited the options available for opposing a major Japanese invasion. Acknowledging that gaining a decisive victory in the opening stages of such a conflict would be impossible, the archipelago’s garrison had orders to retain control of key points on Luzon while awaiting the arrival of a relief force transported by the American Pacific fleet.

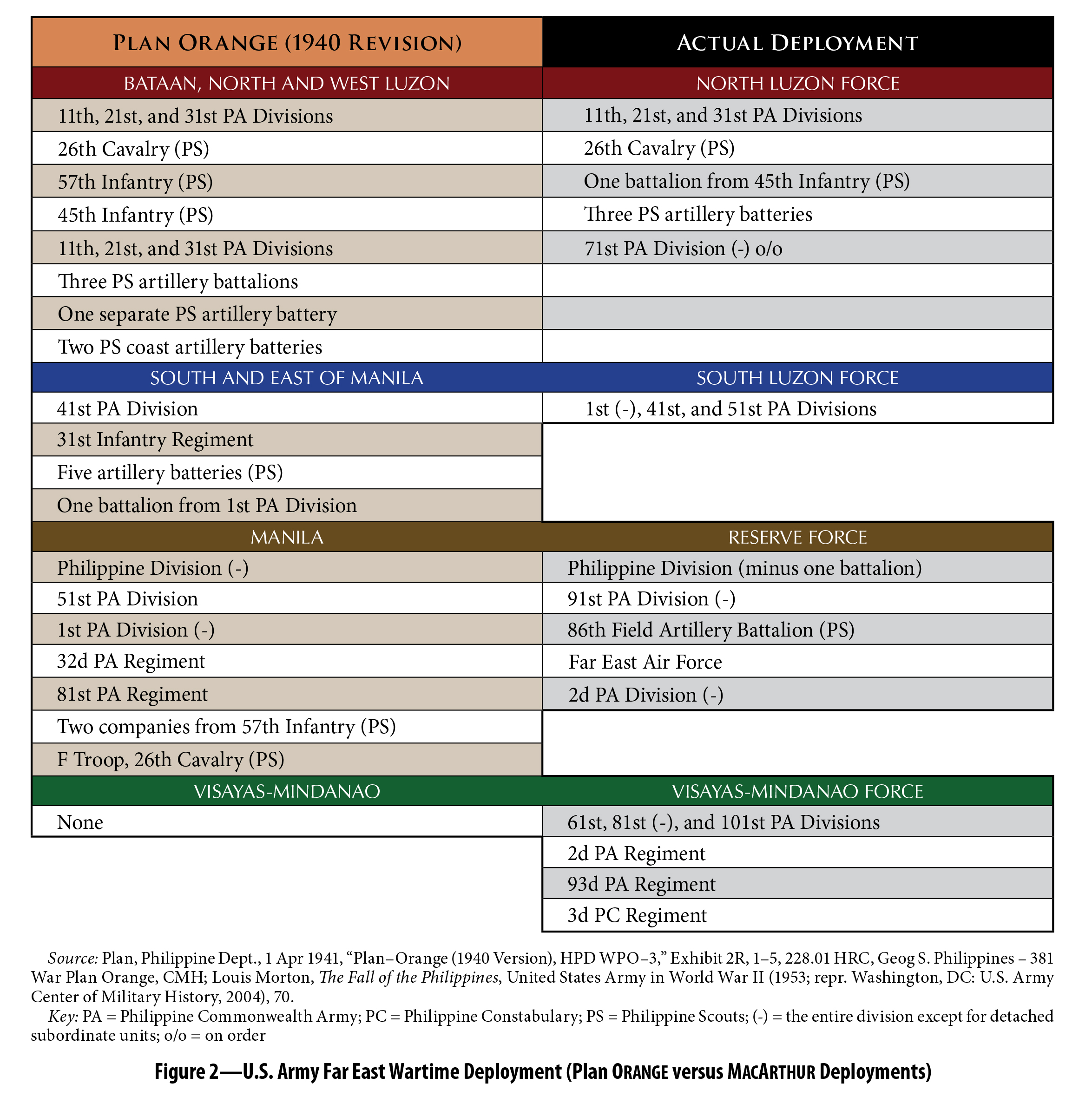

War Plan Orange, which stipulated U.S. military actions during a war with Japan, assigned top priority to denying the use of Manila Bay to Japanese naval vessels. The Philippine Department’s responsibilities, as defined by its commanding officer, Maj. Gen. George Grunert, involved “preventing enemy landings at Subic Bay and elsewhere; failing in this, to eject enemy at the beaches; failing in this, to delay to the utmost the advance of the enemy; to withdraw as a last resort the mobile forces to the Bataan peninsula and defend the entrance to Manila Bay.” As a result, Grunert did not assign troops for the defense of southern Luzon, the Visayas, or Mindanao.

War Plan Orange differed from MacArthur’s fundamental rationale for creating a mass conscript army by focusing on Luzon rather than the entire archipelago. Consequently, Grunert made no plans to employ half of the Philippine Commonwealth Army, and instead planned to use only one regiment apiece from the 81st and 91st Divisions. The Philippine Commonwealth Army leadership did not take well to that concept. Several Filipino officers were convinced the Americans felt no compunctions about sacrificing the entire Philippine Commonwealth Army on the altar of War Plan Orange.

The Americans did anticipate making use of an estimated 65,000 trained Filipino reservists assigned to units on Luzon. The Philippine Department would support their induction by assigning teams—consisting of one U.S. officer, one U.S. enlisted soldier, and two Philippine scouts—to meet each incoming battalion at its respective mobilization center. With a few exceptions, the teams were made up of personnel holding similar specialties, for example, the 31st, 45th, and 57th Infantry supported Philippine infantry regiments, and the Coast Artillery Corps and scout artillery units mobilized Filipino artillery regiments. Upon completion of the Philippine Commonwealth Army’s mobilization, these U.S. teams would remain with their supported units in advisory and command roles.

The Philippine Department detailed how the combined Filipino and American force would defend Luzon in updated instructions entitled “Plan Orange (1940 Revision).” Upon the outbreak of hostilities, the Philippine Division would position U.S. and Philippine scout mobile elements across a wide swath of Luzon. After the Filipinos mobilized their troops, the Americans planned to utilize the 21st Division in western Luzon, the 31st Division at Bataan, and the 41st Division south of Manila. After those divisions moved into position, U.S. troops that had been defending likely landing beaches would withdraw to create a mobile reserve, which also would include the 51st Philippine Division. The city of Manila would be secured by a token U.S. and scout element along with the Philippine 1st and 81st Divisions.

Map2

As 1940 drew to a close, President Roosevelt conceded that he could neither abandon nor evacuate the U.S. garrison in the Philippines. Because of this change of heart, Roosevelt gave the War Department executive approval to fulfill many of General Grunert’s earlier requests. The scouts received not only M1 Garand semiautomatic rifles but also 60-mm. and 81-mm. mortars. Adequate stocks of ammunition, however, did not accompany the latter weapons. The United States also transferred Marine and Army units from China to the Philippines, which increased the number of U.S. combat troops defending the archipelago. In addition, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall sent a coast artillery regiment, fifty pieces of self-propelled 75-mm. artillery, and two battalions of light tanks, along with modern P–40E Warhawk fighters, air warning radars, an aviation engineer battalion, and B–17 Flying Fortress strategic bombers. Additional U.S. reinforcements, including two infantry regiments (161st and 34th), eight field artillery battalions, and fifty Army Air Force A–24 dive bombers, were enroute but were diverted to Hawaii or Australia after war broke out in December 1941.

Roosevelt approved Army plans to increase the number of Philippine scouts from 6,382 to their full authorization of 12,000. Rather than induct personnel with no military experience, Grunert persuaded Quezon to permit trained Filipino reservists to join the scouts. By April 1941, the U.S. Army had selected 3,803 out of more than 5,000 Filipinos who had reported to Fort McKinley and had assigned most of them to the 45th and 57th Infantry Regiments (PS). In addition to beefing up the scouts, the White House increased constabulary authorizations from 7,500 to 15,000, a move that permitted the creation of a second regular division.

Grunert asked the War Department to approve the immediate mobilization of the Philippine Commonwealth Army reserve units on Luzon. The purpose of the call-up, according to the Philippine Department commander, was to provide the Filipino units with two to four months of combat-oriented instruction under the “complete command, supervision, and control” of U.S. forces. Grunert’s recommendation reflected a keen awareness that Philippine Division regulars and reserve divisions of the Philippine Commonwealth Army possessed profoundly different levels of proficiency. Although the increase of scouts gained White House approval, Roosevelt did not authorize an immediate call up of the Philippine Commonwealth Army.

Filipino Service in U.S. Army Forces Far East

On 26 July 1941, President Roosevelt announced that the United States had frozen Japanese financial assets in retaliation for Tokyo’s occupation of Vichy French Indochina. The announcement triggered Japanese plans to obtain needed resources by seizing Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies. The Japanese also intended to seize the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island to preempt an American counterattack against the eastern flank of their invasion force. As the Japanese accelerated preparations for war, Roosevelt ordered the induction of all the commonwealth’s organized military forces into the armed forces of the United States in accordance with the provisions of Section II(a) of the Tydings-McDuffie Act. He also recalled MacArthur to active duty with the rank of major general and placed him in command of U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE).

General MacArthur immediately realized that his status as commanding general opened up opportunities to acquire the modern weapons that the Philippine Commonwealth Army sorely needed. Rather than adopt the plans developed by Grunert, MacArthur assigned key tasks to all twelve Filipino regular and reserve divisions. Not waiting for formal permission from the War Department, MacArthur redrew existing operational boundaries to establish four new commands: North Luzon Force, South Luzon Force, Reserve Force, and the Visayas-Mindanao Force. The newly created 2d Division, composed of constabulary personnel, drew the assignment of securing Manila. The bulk of the U.S. personnel, with the exception of a small contingent of scout officers and U.S. adviser/instructors assigned to the Visayas-Mindanao Force, remained on Luzon. On 21 November 1940, General Marshall notified MacArthur that he had approval to implement the revised defensive scheme.

The new plan differed from prewar strategy focusing on defending Manila in that MacArthur made use of the remainder of the Philippine Commonwealth Army to defend the Visayas-Mindanao region while dedicating more troops to southern Luzon. He also decided to use Filipino units to defend potential landing beaches on Luzon. MacArthur’s newfound emphasis on defeating an invader at the water’s edge, rather than counterattacking the initial lodgment using the general reserve, received official confirmation after a USAFFE order, dated 3 December 1941, stipulated there would be “no withdrawal from the beaches.” The changes convinced many American officers that MacArthur now would place little emphasis on conducting a delaying action into Bataan.

MacArthur’s increased reliance on Philippine units resulted in Congress voting to send $269 million in military aid to the archipelago. MacArthur knew that when the new weapons arrived, Filipino soldiers would need to be taught how to operate them. Consequently, USAFFE announced that each of the reserve divisions would receive forty U.S. Army officers and twenty U.S. Army noncommissioned officers (including Philippine scouts) as adviser/instructors. The Philippine Division provided some of these individuals, and units in the continental United States contributed another 425 personnel. In addition to transferring the American adviser/instructors, USAFFE reassigned 2,300 scouts to commonwealth units in an effort to offset the lack of experienced noncommissioned officers. The reequipping process would take time to implement, but the USAFFE commander did not believe the Japanese would invade before April 1942.

Additional resources from the United States did not solve the problem of inadequate numbers of Filipino officers. To help overcome these shortages, USAFFE selected the most promising individuals of each reserve training class for an additional six months of training as noncommissioned officers, and the best of the latter were commissioned as third lieutenants in the Philippine Commonwealth Army. Other third lieutenants came from Reserve Officer Training Corps units established at universities and colleges. Another measure involved promotions of lower-ranking officers to fill existing vacancies in higher grades. In early August 1941, for example, those promoted by the Philippine Commonwealth Army included three new colonels, nine lieutenant colonels, sixteen majors, and thirty-six captains. The 1940 and 1941 graduating classes of the Philippine Military Academy were assigned en masse to the 1st Division, although the latter class would not report until mid-December.

Recognizing that few Filipinos possessed high-level command experience, Grunert’s staff anticipated filling Philippine Commonwealth Army vacancies with American officers. The Philippine Department allocated twenty-eight infantry officers, six cavalry officers, five field artillery officers, and five coast artillery officers to command at battalion level and above. This number grew as more U.S. officers, both reservists and regulars, became available. Americans commanded twenty-four of the thirty Filipino reserve infantry regiments. Americans also led eight of the ten Philippine reserve artillery regiments. Filipino officers—including Brig. Gen. Mateo M. Capinpin with the 21st Division, General Lim with the 41st Division, recently promoted Brig. Gen. Fidel Segundo of the 1st Division, and Guillermo Francisco, now a brigadier general, of the 2d Division—led four of the twelve Philippine divisions.

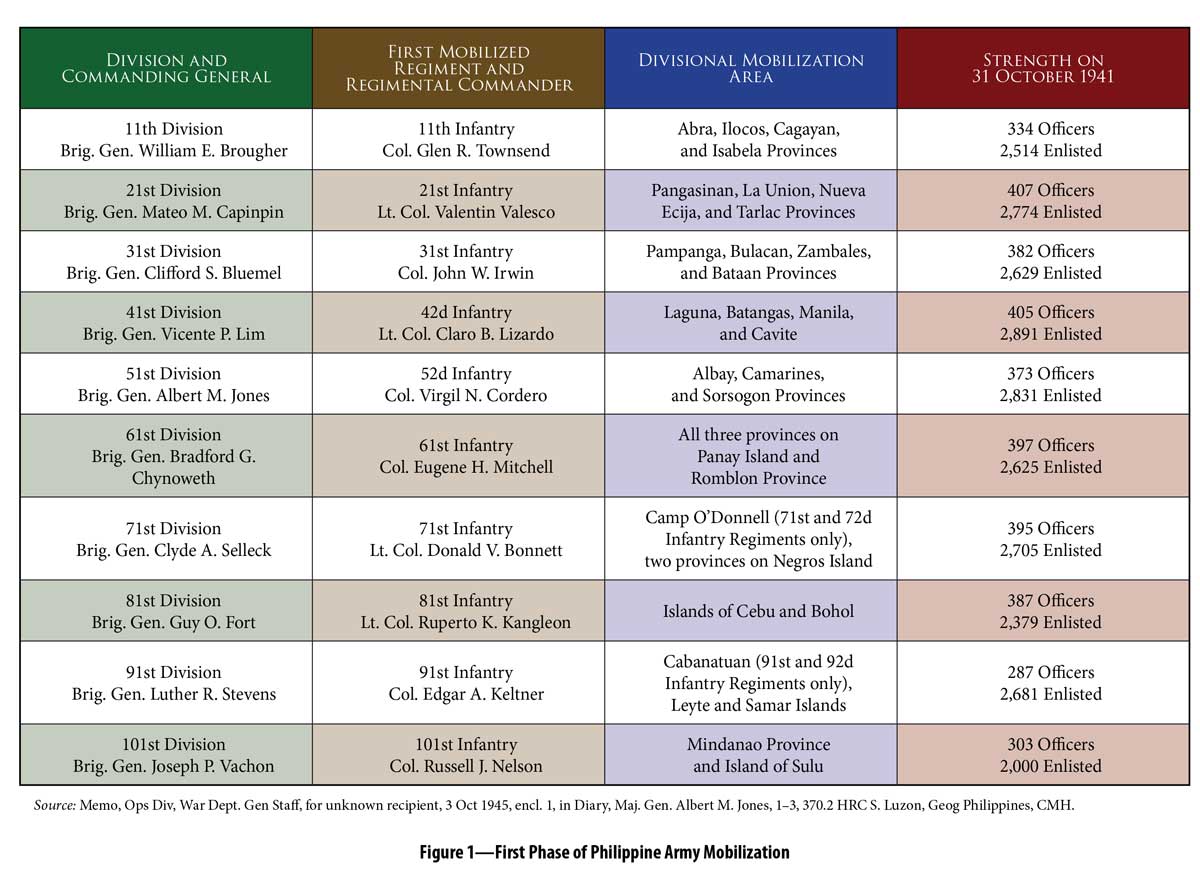

With the exception of the constabulary units assigned to the 2d Division, which had assembled in Manila in mid-July 1941, the mobilization of ten reserve divisions began with the induction of one infantry regiment on 1 September. Divisional officer cadres, selected noncommissioned officers, and several divisional engineer battalions began assembling in mid-September. The decision to mobilize the engineers sooner than originally planned stemmed from the need to build roads, depots, and cantonment areas. Some units, such as the 11th Engineer Battalion, also were tasked to establish schools for follow-on units. In addition, several constabulary formations assigned to the 2d Division were unable to secure transport to Manila (Figure 1).

The second regiment from each division mobilized on 1 November, followed a month later by the third regiment. Mobilization of the entire force, including both regular divisions, theoretically would have been completed by 15 December. However, both the second and third phases experienced significant delays. Full mobilization involved not only the assembly of troop units but also the construction of additional housing and training facilities. Although the mobilization centers could accommodate the initial intake, they were insufficient to support follow-on units. The Visayas-Mindanao Force met some equipment shortages by pilfering Reserve Officer Training Corps stocks, but Filipino reservists with the 72d, 82d, and 92d Infantry Regiments ultimately went to war armed only with bolo knives.

The month of November also witnessed the mobilization of divisional artillery regiments, although this process proved to be a painful one. Competition for limited shipping assets also held up the movement of personnel and equipment. As a result, USAFFE organized some artillery units in Mindanao, Cebu, and the Visayas as provisional infantry formations, pending the arrival of their field pieces. The emphasis on training infantry in the early years of the Commonwealth Army’s existence had created a shortage of trained artillery soldiers. At a minimum, Filipino artillery reservists waited several weeks before they received weapons. At least three field artillery regiments never received any cannons because the ships carrying the weapons from Luzon were sunk enroute or the onhand stocks were insufficient to meet their needs.

The reorganization of the USAFFE chain of command encountered less severe obstacles. American officers exclusively occupied command positions above division level. MacArthur created the North and South Luzon Forces, each the equivalent of a corps headquarters, using personnel drawn from the Philippine Division and staffs of existing army installations. He also formed two less robust command and control elements for the Manila Bay and Visayas-Mindanao regions. Brig. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright commanded the North Luzon Force while Brig. Gen. George M. Parker Jr. led the South Luzon Force. Brig. Gen. William F. Sharp received command of the Visayas-Mindanao Force while Brig. Gen. George F. Moore headed the Manila Bay defenses. American and Philippine scout strength in the Philippines, which had numbered 21,550 officers and enlisted personnel on 30 July, grew to 31,102 by the end of November. In addition to the U.S. personnel, the Philippine Commonwealth Army numbered 90,000 by 15 December.

Although the numbers seemed impressive, they paled in comparison to USAFFE’s responsibilities. The 7,100 islands making up the Philippines had 22,000 miles of potential landing sites. General Wainwright’s North Luzon Force was responsible for defending against an enemy landing on western and northern Luzon. In addition to the 26th Cavalry (PS), his command included the 11th Division, which mobilized in the Lingayen Gulf area; the 21st Division, mobilizing in north central Luzon near Tarlac; the 71st Division, assembling 25 miles northwest of Clark Field at Camp O’Donnell, and the 31st Division, forming on the coastal plain of Luzon, west of the Zambales Mountains. The 91st Division, then mobilizing northeast of Manila at Cabanatuan, was attached to Wainwright’s command, although MacArthur designated it as his strategic reserve. USAFFE shipped the 71st and 91st Divisions to Luzon from Leyte and Samar, albeit minus their third regiments and divisional artilleries.

The South Luzon Force, responsible for defending against hostile amphibious landings south of the capital, consisted of two Philippine Commonwealth Army reserve divisions augmented by portions of the 1st Division. The Philippine and 91st Infantry Divisions protected the northeast shore of Manila Bay between Manila and San Fernando. General Sharp’s Visayas-Mindanao Force, composed of three Philippine Commonwealth Army reserve divisions, had the mission of preventing the enemy from establishing airfields on Panay, Negros, Bohol, Samar, Leyte, Mindanao, and southern Mindoro, rather than defending those islands against amphibious assaults (Map 2).

MacArthur, who believed that he had enough time to prepare the Philippine Commonwealth Army before the Japanese landed, modified the defensive plans developed by the Philippine Department (Figure 2). The U.S. soldiers originally allocated to defending the most likely landing beaches on Luzon were replaced by Filipino troops, despite the fact that American units possessed greater numbers and firepower, better training, and superior command and control. MacArthur wanted the Filipinos to defend the beaches because an enemy amphibious force is normally most vulnerable during the first moments of a landing. This factor would offset the Philippine Commonwealth Army’s lack of firepower to a considerable degree, allowing Filipino reserve units to make significant contribution despite their shortcomings.

General Grunert disagreed with this scenario, stating, “The strength of the U.S. troops in the Philippines is so limited that if the bulk of the Philippine Division is held in reserve, the forces at the beaches will be so weak that they will be unable to prevent landings or inflict serious losses on the enemy when he is most vulnerable.” With only light opposition at the beaches, Grunert presciently noted, enemy forces would be able to push inland so rapidly from several landing points that it would be impossible to meet them effectively with the reserves. Such rapid action by the enemy would “prevent the mobilization of a large part of the Philippine [Commonwealth] Army and seriously jeopardize the supplies in the Manila area before they could be moved to Bataan.” For this reason, Grunert proposed to retain a substantial number of American troops in the beach defenses even after mobilizing the Philippine Commonwealth Army divisions. In response, MacArthur, who did not appreciate criticism of his operational plans, unceremoniously relegated Grunert to the sidelines.

The sequential mobilization of Philippine regiments resulted in a wide disparity of combat readiness within each division. Within the 31st Division, the 31st Philippine Infantry Regiment received almost three months of training, while the 32d and 33d Philippine Infantry Regiments had five and two weeks respectively. The personnel in some battalions had fired fifty rounds on the range, whereas other soldiers fired as many as twenty-five rounds and as few as zero. The 41st Division’s 41st Philippine Infantry Regiment received five weeks of training; the 42d Philippine Infantry Regiment had thirteen weeks; and the 43d Philippine Infantry Regiment virtually none. In the 51st Division, all of the soldiers of the 52d Philippine Infantry Regiment received three months of training. Within the 51st Philippine Infantry Regiment, officers and key noncommissioned officers received two months of training, while other noncommissioned officers and privates had one month. Whereas the officers and key noncommissioned officers of the 53d Philippine Infantry Regiment had three months training, the bulk of the noncommissioned officers and enlisted soldiers received no training whatsoever before entering combat.

The 11th Division provides a typical example of readiness within the supporting arms. Its field artillery regiment did not go into action until late December, and, even then, it had to make do with 60 percent personnel strength and eighteen of its twenty-four 3-inch cannons. USAFFE allotted only eight 75-mm. cannons to the 51st Division, which meant that two batteries began training as field artillery units while the remainder drew rifles and began training as a provisional infantry unit. To make matters worse, the artillery crews and fire direction personnel had not trained adequately, which greatly reduced their accuracy and responsiveness. There was also a severe shortage of spare parts, and much of the ammunition proved defective, having spent several decades in depots.

The lack of qualified personnel was most apparent when the senior American instructor with the 21st Artillery Regiment assigned 2d Lts. Melchior Acosta and Geraldo Mercado, both recent Philippine Military Academy graduates, to command field artillery battalions—a position normally held by a major or lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. Practically no higher-ranking Filipino officers were capable of functioning efficiently as staff officers, and it was necessary to replace them with American reservists before commonwealth units went into action.

Although commonwealth soldiers were eager to learn the tradecraft of war, their enthusiasm proved to be a poor substitute for reliable weapons and intensive training. The U.S. Army official history, commenting on the late December 1941 Japanese landings at Lingayen Gulf, noted, “Only the Scouts of the 26th Cavalry had offered any serious opposition to the successful completion of the Japanese plan. The untrained and poorly equipped Philippine Commonwealth Army troops had broken at the first appearance of the enemy and fled to the rear in a disorganized stream.” The uneven performance of Philippine reserve divisions at the onset of the war surprised no one, with the possible exception of MacArthur.

Conclusion

As the campaign wore on, the Philippine scouts and the 2d Division gained a number of tactical successes, providing ample evidence of how Filipinos could fight when well-led, adequately armed, and intensively trained. As one American tank battalion commander later noted, “Casualties in the Scouts were high, but their determination and bravery was unsurpassed. They never complained, accepting whatever fate might bring them.” While Filipino reserve divisions suffered defeat in a number of early engagements, their personnel grew more confident and proficient as the campaign wore on. In fact, the Japanese had to halt the initial phase of their operation to transport additional troops to the Philippines to overcome unexpectedly fierce resistance. Even though the subsequent battles for Bataan and Corregidor dominate historical accounts of that period, Filipino troops on Mindanao held their attackers at bay until ordered to surrender by USAFFE in May 1942.

2d Lt. Roberto Lim, son of Vicente Lim, shown here in March 1942 (Library of Congress)

The United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands committed significant numbers of native troops against Japanese invading forces that swept across Southeast Asia during the opening months of World War II in the Pacific. In sharp contrast to the American relationship with the Filipinos that had begun at the turn of the century, both Great Britain and the Netherlands employed native formations to maintain order in their respective Malayan and East Indies colonies for a century or more. The events that transpired after the Japanese conquered not only Malaya and the East Indies, but also the Philippines, are therefore even more noteworthy. Thousands of colonial troops who served with the British and Dutch switched sides after surrendering. Events in the Philippines took a far different course as former scouts and constabulary soldiers joined forces with ordinary Filipinos to wage a relentless guerrilla war against their occupiers, paving the way for MacArthur’s return in 1944. The fighting that took place before and after the USAFFE capitulation serves as a testament to the unbreakable bonds forged between Americans and Filipino soldiers.

Notes

1. The Spanish pacified the Philippines between 1565 and 1600. The Macabebe originally were on the side of the rebels during the insurrection, but a dispute among top insurgent leaders that resulted in the death of a Macabebe senior officer may have convinced them to shift allegiances. Mario E. Orosa, “The Macabebes,” Orosa Family Web Site, 10 Sep 2013, http://orosa.org/TheMacabebes.pdf (accessed 13 Oct 2023).

2. Charles H. Franklin, History of the Philippine Scouts, 1899–1934 (Fort Humphreys, DC: Historical Section, Army War College, 1934), 5, Organizational History Branch Files (Companies, Battalions, Regiments, Brigades, and Divisions), Field Programs Division (hereinafter Org Hist Br Files), U.S. Army Center of Military History, Washington, DC (hereinafter CMH).

3. Maj. James R. Craig, “A Federal Volunteer Regiment in the Philippine Insurrection: The History of the 32nd Infantry (United States Volunteers) 1899–1901” (master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2006), 72–75, p4013coll2_575, Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Digital Library, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

4. Franklin, History of the Philippine Scouts, 9–10.

5. The Statues at Large of the United States of America from December, 1899, to March, 1901, and Recent Treaties, Conventions, Executive Proclamations, and the Concurrent Resolutions of the Two Houses of Congress, vol. 31 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1901), 757–58, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl//llsl-c56/llsl-c56.pdf (accessed 12 Dec 2023).

6. The planners doubtless were unaware that the Japanese Empire had been making plans to invade the Philippines since the end of the sixteenth century. None of these plans came to fruition because the Japanese lacked the naval capacity for such an invasion. Stephen Turnbull, “Wars and Rumours of Wars: Japanese Plans to Invade the Philippines, 1593–1637,” Naval War College Review 69, no. 4 (Autumn 2016): 107–18.

7. Edward S. Miller, War Plan ORANGE: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 54.

8. The constabulary remained organized as separate companies, spread among five (later six) administrative districts until 1935, when they were reorganized into six regiments, each consisting of two battalions (except for three battalions authorized for the Mindanao regiment). Lt. Col. Ambrosio P. Peña, Bataan’s Own (Muñoz Press, Manila: 2d Regular Division Association, 1967), 15–27.

9. The Register of Graduates and Former Cadets of the United States Military Academy (West Point, NY: Association of Graduates, 2005), 5–15; George Munson, “The Best of The Best (91st Coast Artillery, Philippine Scouts): A Short History,” Units & Personnel, Corregidor – Then and Now, 2000, http://corregidor.org/chs_munson/91st.htm (accessed 15 Nov 2023).

10. “Report of the Adjutant General,” in War Department Annual Reports, 1918, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 171.

11. GO 21, Headquarters, Philippine Dept., 5 Apr 1918, Manila, P.I., in War Department Annual Reports, 1918, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 172.

12. “Report of the Governor General of the Philippines, January 1 to December 31, 1917,” in War Department Annual Reports, 1918, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1918), 1.

13. “Report of the Chief of Militia Bureau,” in War Department Annual Reports, 1918, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 1132.

14. Report of the Governor General of the Philippines to the Secretary of War, January 1, 1919 to 31 December, 1919 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 26.

15. “Report of the Governor General of the Philippines, January 1 to December 31, 1917,” 2.

16. Ltr, Ofc Ch Mil History to HQ, Personnel Center, 6020 Service Unit, Oakland Army Base, n.d., sub: Information on Philippine NG, Org Hist Br Files, CMH.

17. The U.S. Army end strength dropped once more to 125,000 by 1922. Richard W. Stewart, ed., American Military History, vol. 2, The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917–2003, Army Historical Series (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2005), 57; Robert K. Griffith, Men Wanted for the U.S. Army: America’s Experience with an All-Volunteer Army Between the World Wars (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), 29–93, 233.

18. The National Defense Act of 1920 also stipulated that all officers in the scouts holding U.S. citizenship had to be reintegrated into the Regular Army. Only 62 of the 188 officers in the scouts were eligible for reintegration. Report of the Adjutant General of the Army to the Secretary of War, 1921 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921), 18, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015035881591&seq=3 (accessed 12 Dec 2023).

19. Franklin, History of the Philippine Scouts, 22–24.

20. Ibid., 29.

21. War Dept. Cablegram 1063, 29 Apr 1921, per AG 322.82 (21 Apr 21), Unit Data Card, HQ and Mil Police Co, 12th Inf Div, Org Hist Br Files, CMH.

22. Constituted in 1921 and organized in 1922, the 23d Brigade (PS) was the parent organization of the 45th and 57th Infantry Regiments (PS). The 24th Brigade initially oversaw the 15th and 31st Infantry Regiments (U.S.) before being redesignated as a Philippine scout formation with responsibility for the inactivated 44th and 62d Infantry Regiments (PS).

23. Annual Report of the Secretary of War, 1920 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 26; Report of the Secretary of War to the President, 1922 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1922), 137.

24. Although inactivated, the 43d Infantry Regiment (PS) remained assigned to the Philippine Division. John E. Olson, The Philippine Scouts (San Antonio, TX: Philippine Scouts Heritage Association, 1996), 78–80.

25. Franklin, History of the Philippine Scouts, 27.

26. Ibid., 29.

27. GO 8, War Dept., 1924, para. 21, 91st Coast Artillery (Philippine Scouts); 4th Indorsement, War Dept., AGO, 26 Oct 1925, Commandant, Army War College, Historical Section, Washington, DC, 92d Coast Artillery (Philippine Scouts); both in Org Hist Br Files, CMH.

28. GO 36, 27 Jun 1920, in War Department General Orders and Bulletins, 1920 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921), 5; James P. Finley, “The Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Huachuca,” Huachuca Illustrated: A Magazine of the Fort Huachuca Museum 1 (1993), 54, https://home.army.mil/huachuca/application/files/4316/6577/8846/Vol_1_1993_Buffalo_Soldiers.pdf(accessed 13 Dec 2023).

29. “Troops Mutiny, Dissatisfied Natives, Philippine Episode,” Sydney Morning Herald, 8 Jul 1924, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/16152584 (accessed 6 Jul 2012).

30. Chris Yeazel, “America’s Sepoys (Part II),” Philippine Scouts Heritage Society (Fall 2008): 11–12, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e10ea57f51cd16ca72b46b4/t/5e7ee35486693d3dcc07fd4f/1585374037113/2008-PSHS-Fall.pdf (accessed 12 Dec 2023).

31. “Philippine Scout Rebellion,” Straits Times, 29 Aug 1924, 9, http://newspapers.nl.sg/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19240829.2.67.aspx (accessed 6 Jul 2012).

32. Richard B. Meixsel, “An Army for Independence? The American Roots of the Philippine Army” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, 1993), 181–90, UA853.P6.M44, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

33. Brian M. Linn, Guardians of Empire, The U.S. Army and the Pacific, 1902–1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 158.

34. Meixsel, “An Army for Independence?” 172.

35. For example, no large-scale combined maneuvers were held in the continental United States during 1925 because of lack of funds. Report of the Secretary of War to the President, 1926 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1926), 45–46.

36. Munson, “The Best of The Best (91st Coast Artillery, Philippine Scouts): A Short History,” n.d.

37. Ibid.

38. Senator Millard Tydings and Representative John McDuffie chaired the respective Senate and House committees on insular affairs.

39. “Manuel L. Quezon,” Macarthur, Features, American Experience, PBS, n.d., http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/macarthur/peopleevents/pandeAMEX108.html (accessed 15 Nov 2023).

40. Daniel D. Holt and James W. Layerzapf, eds., Eisenhower: The Prewar Diaries and Selected Papers, 1905–1941 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 287–88.

41. Ibid., 294–95.

42. James F. Lacy, “Origins of the United States Army Advisory System: Its Latin American Experience, 1922–1941” (PhD diss., Auburn University, 1977), 88, FL1418.L3, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

43. Report of the Secretary of War to the President, 1935 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935), 20.

44. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Proclamation 2148, “Establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines,” The American Presidency Project, 14 Nov 1935, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-2148-establishment-the-commonwealth-the-philippines (accessed 9 Dec 2023).

45. Philippine Independence Act, PL 73–127, 48 Stat. 456 (24 Mar 1934), 459, https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/48/STATUTE-48-Pg456.pdf (accessed 12 Dec 2023).

46. D. Clayton James, The Years of MacArthur, vol. 1, 1880–1941 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 484–86.

47. Marconi M. Dioso, The Times When Men Must Die: The Story of the Destruction of the Philippine Army during the Early Months of World War II in the Pacific, December 1941–May 1942 (Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing, 2010), 11.

48. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 312.

49. Ibid., 295.

50. Philippine Commonwealth Act No. 1, “An Act to Provide for the National Defense of the Philippines, Penalizing Certain Violations Thereof, Appropriating Funds Therefor, and for Other Purposes,” Chan Robles Virtual Law Library, 21 Dec 1935, http://www.chanrobles.com/commonwealthacts/ commonwealthactno1.html (accessed 11 Dec 2023).

51. Ibid.

52. Biography, Maj. Gen. Guillermo B. Francisco, Khaki and Red: Constabulary Journal and General Magazine, Jul-Aug 1963, 16, https://repository.mainlib.upd.edu.ph/omekas/files/original/78c9e08f0718a3a8cdb0e47de2a2361bb3554774.pdf (accessed 13 Dec 2023).

53. Ricardo Trota Jose, The Philippine Army, 1935–1942 (Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1992), 51.

54. “1st Infantry Division (Philippines),” Wikipedia, 9 Nov 2023, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Infantry_Division _(Philippines).

55. Jose, Philippine Army, 56–57.

56. Ofc Ch Mil History (OCMH) Study No. 94, Gen History Br, Ofc Ch Mil History, Jun 1973, “The Status of Members of the Philippine Military Forces during World War II,” 7–9, Author Files.

57. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 318–19.

58. Boyd L. Dastrup, King of Battle: A Branch History of the U.S. Army’s Field Artillery (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1993), 194–95.

59. Only the 2d Division received sufficient .50-caliber machine guns to form a provisional antitank/antiaircraft battalion. Peña, Bataan’s Own, 45.

60. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 319.

61. Louis Morton, The Fall of the Philippines, United States Army in World War II (1953; repr., Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2004), 10.

62. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 316.

63. Jose, Philippine Army, 65–66.

64. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 324–25.

65. Ibid., 343, 345.

66. Ibid., 327.

67. James, Years of MacArthur, 544.

68. Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 10.

69. James, Years of MacArthur, 521–25.

70. Ibid., 518.

71. Kerry Irish, “Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines: There Must be a Day of Reckoning,” Journal of Military History 74, no. 2 (Apr 2010): 456.

72. Jose, Philippine Army, 101–3.

73. Ibid., 52.

74. Ibid., 119–21.

75. Holt and Layerzapf, Eisenhower, 430.

76. James, Years of MacArthur, 536–37.

77. Ibid., 537.

78. Reduced defense expenditures continued through 1940 and were 14 percent lower than the preceding year. In 1941, the budget shrank even more. Irish, “Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines,” 467; James, Years of MacArthur, 537.