A Legislative History of The General Survey Act

By Matthew T. Pearcy

Article published on: August 1, 2024 in the Army History Fall 2024 issue

Read Time: < 18 mins

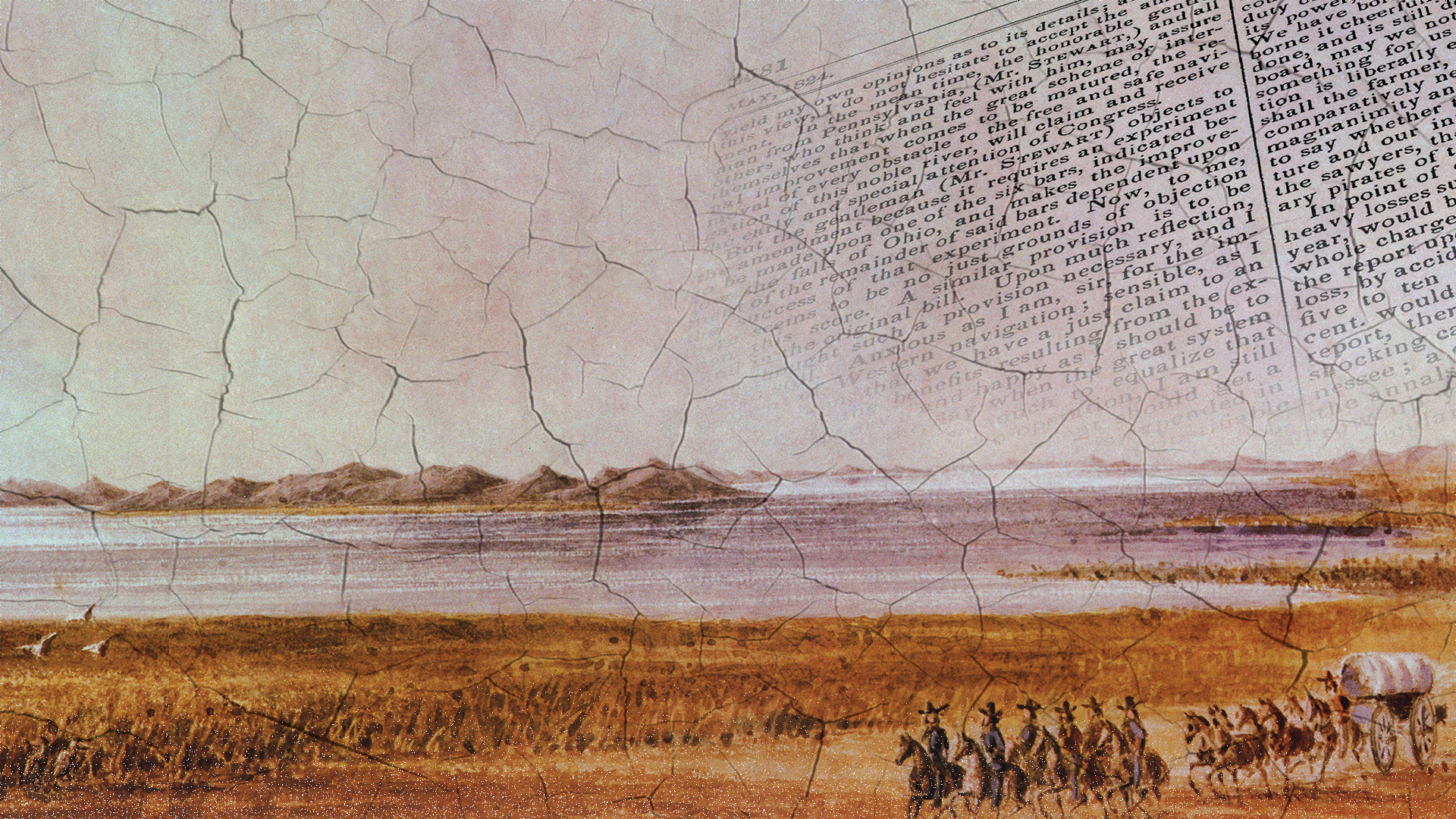

A painting of a nineteenthcentury survey party in northern New Mexico by J. J. Young. The General Survey Act authorized the use of Army engineers to survey road and canal routes throughout the growing United States.

National Archives

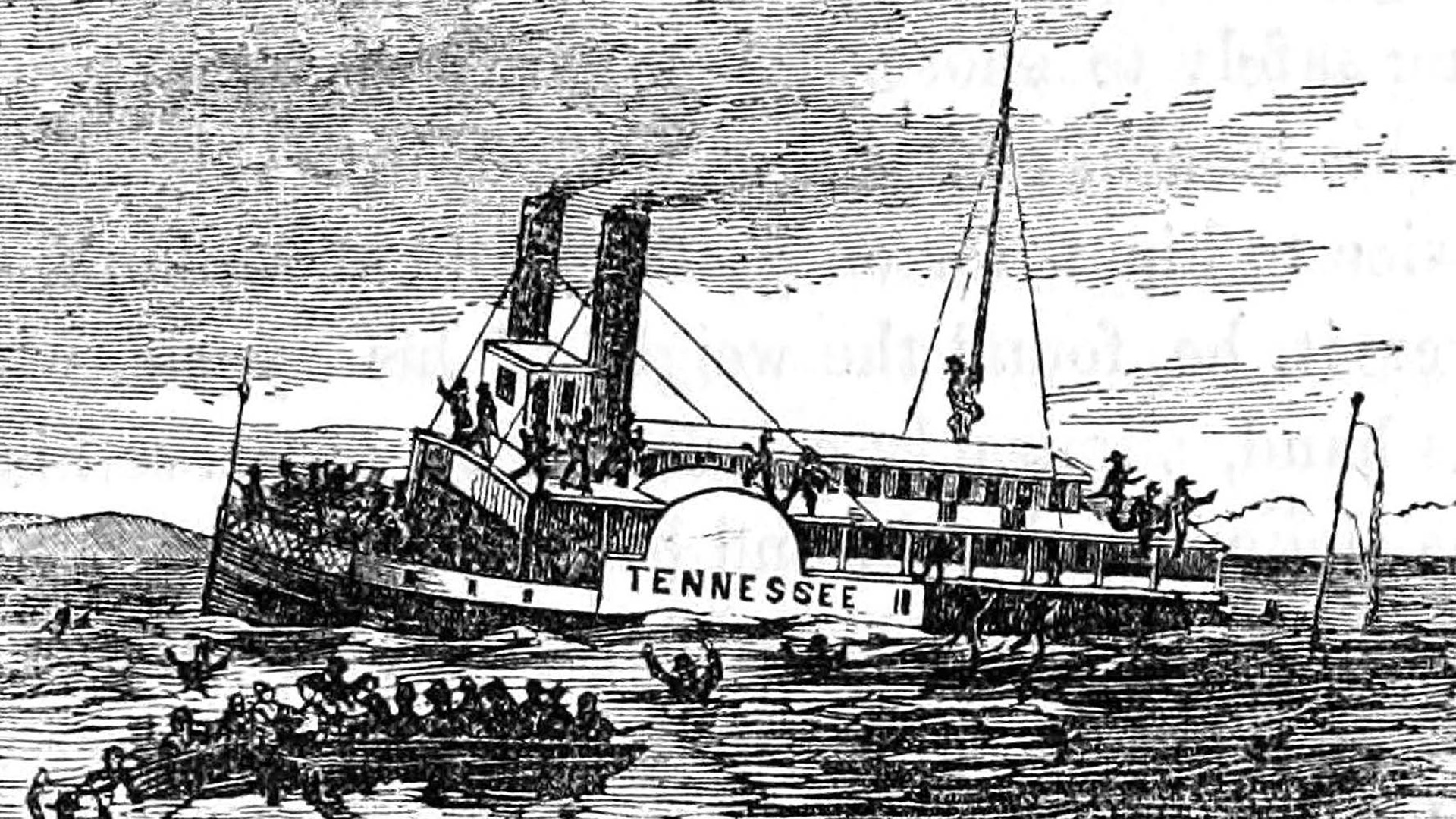

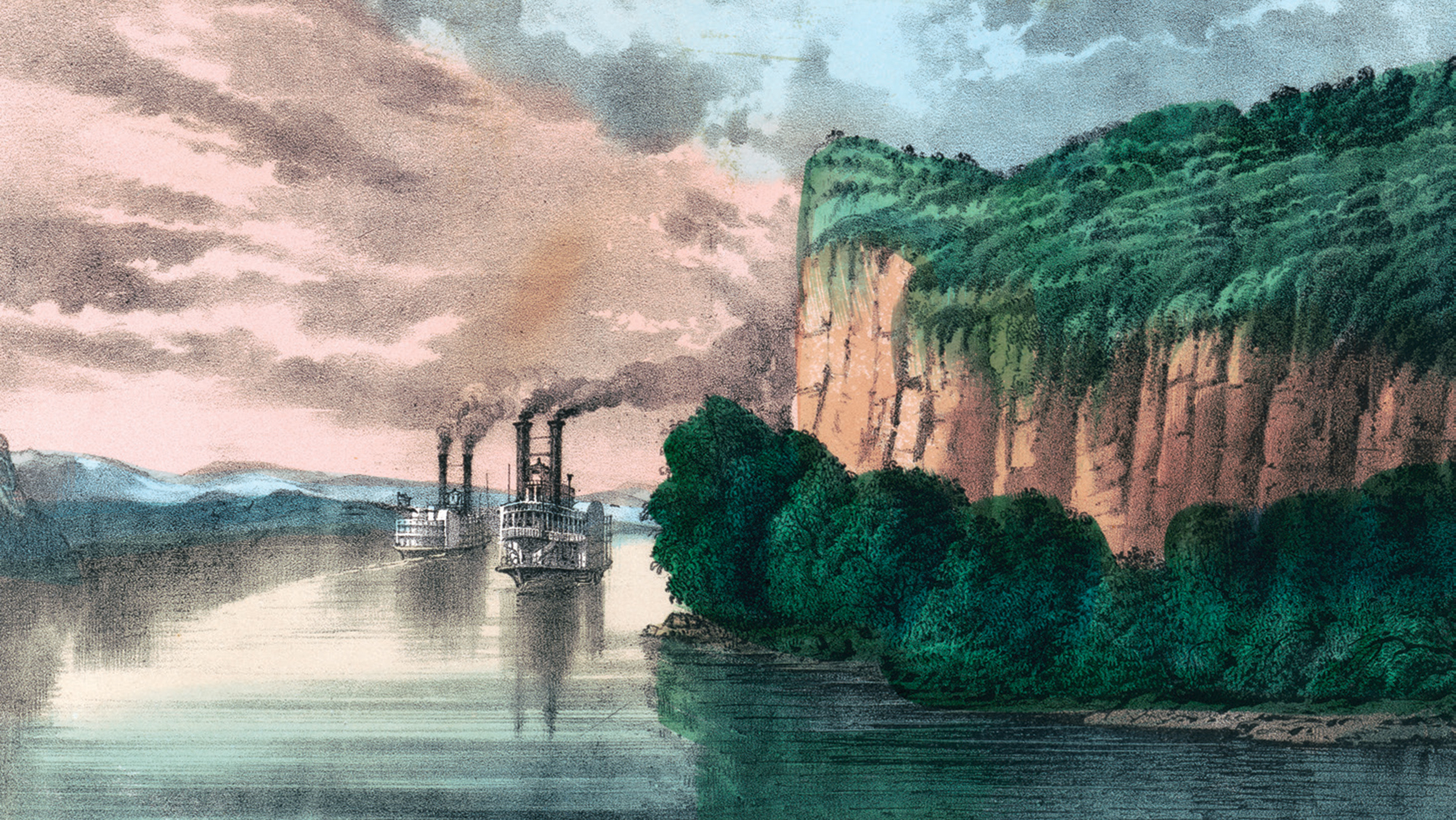

On a blustery winter night in February 1823, the steamer Tennessee ploughed her way upstream through the twisting currents of the Mississippi River. It was snowing, and visibility on the river was poor. The steamship carried more than 180 men, women, and children, with many already asleep for the night and tucked away in their rooms. Some gathered in the spacious cabin, eating and drinking and enjoying the evening together. While still under a full press of steam, the Tennessee struck a large snag near Natchez, Mississippi, tearing a 6-foot gash in the hull. The ship rapidly took on water, and panic and confusion spread among the passengers. The captain acted quickly to lower the longboat, which filled to near-sinking before shoving off to shore. Dozens who were left behind jumped into the river. The strongest swam ashore, but many others drowned in the frigid and turbulent waters. Fully a third of the passengers died that night, most in the first five minutes of the disaster. The ship was completely wrecked, with lost cargo estimated at $80,000. The dead, more than a dozen of whom were never identified, came from all over the country and as far away as Kentucky, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts.

Two hundred years later, this incident mostly has been forgotten, but the sinking of the Tennessee was one of the first great river disasters in U.S. history. Newspapers throughout the country reported on the tragedy. It was a topic of conversation for many months and ultimately worked in commune with a variety of other factors to drive the passage of two vital pieces of congressional legislation in 1824: a General Survey Act authorizing Army engineers to conduct road and canal surveys, and a Rivers and Harbors Act to fund navigational improvements on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.1 Together, these laws ushered in a new era of civil works legislation that reshaped the Army Corps of Engineers and, in the late 1830s, birthed its sister organization, the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers.

A sketch showing the sinking of the steamboat Tennessee.

Library of Congress

The Tennessee disaster drew public attention and provided a powerful emotional catalyst for government action on internal improvements on American rivers and waterways, but much of the groundwork was already in place. The War of 1812 brought about a significant expansion of the Corps of Engineers, including the addition of eight topographical engineers (or “topogs”) and an equal number of assistants. Much of the organization was dismantled after the war, but legislation in April 1816 restored six topogs to the peacetime Army, a vital recognition of their significance to the service and of an emerging appreciation for the importance of both military and civil engineering works, especially surveying and roadbuilding. In the early part of the nineteenth century, the peacetime Army engineers focused primarily on the construction of Third System coastal fortifications first authorized in 1816, whereas the topogs assumed responsibility for a limited array of civil works improvements such as roads and canals. These delineations were drawn tightly, and the pecking order within the Army clearly favored the engineer officers over the topogs, though the latter enjoyed a “rising reputation” throughout these decades.2

A sketch of John C. Calhoun, ca. 1840

Library of Congress

The South Carolinian John C. Calhoun (1782–1850), then a member of Congress, promoted the cause of civil engineering with his Bonus Bill of 1817, which earmarked surplus monies from the lucrative Second Bank of the United States for an internal improvements fund. President James Madison favored the bill but vetoed it as unconstitutional because he felt that the Commerce Clause of Article I, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution did not expressly give Congress the power to fund the building of roads and canals. This interpretation and the absence of any relevant Supreme Court rulings had the effect of restricting civil works funding, but advocates for internal improvements continued to make their case, pointing to the “necessary and proper” clause under that same Section 8. It contends that Congress has the legislative power “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” the other powers explicitly granted by the Constitution.3 The Supreme Court affirmed that interpretation of the “elastic clause” in its McCulloch v. Maryland ruling in 1819.4

As secretary of war under President James Monroe, Calhoun continued to press his views in his “Report on Roads and Canals” (1819), which advocated for extensive use of Army engineer and topographical support for surveys of public works. Three years later, in 1822, Maj. Isaac Roberdeau of the Topographical Engineers underscored the value of the topogs in public improvements and argued for a more active role for them in assisting transportation and communications, in addition to their vital work on national defense. In December of that same year, two leading Army engineers submitted the landmark “Report on the Board of Engineers on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.” Written by Maj. Simon Bernard and Maj. Joseph G. Totten, and signed by Alexander Macomb, the “Colonel Commandant of the U.S. Engineers,” the report constituted the first official U.S. survey of those two mighty American waterways. It called for extensive improvements, including the removal of obstacles, sandbars, and other obstructions in the Ohio River; the construction of a canal on the Indiana side to circumvent the falls above Louisville, Kentucky; and the removal, particularly on the Mississippi River, of dangerous snags including floating or underwater tree stumps or large branches hazardous to navigation. The timing of this report proved fortuitous, as Congress turned its attention once again to the issue of internal improvements.5

A. Major Totten Library of Congress, B. A bust of Simon Bernard U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History C. Portrait of Alexander Macomb by Thomas Sully, showing Macomb as a major general when he was the commanding general of the U.S. Army. U.S. Army Art Collection

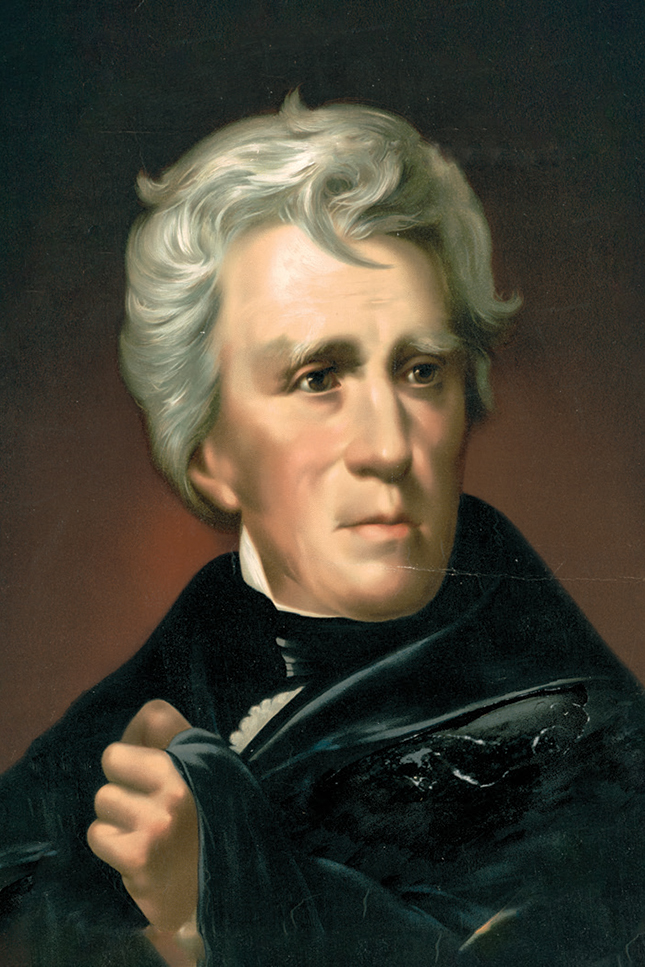

Debate in the House of Representatives began in February 1824, a time of relative political upheaval in the United States. As the sun set on the period of relative domestic political harmony known as the “Era of Good Feelings” (1817–1824), the Democratic-Republican Party established by Thomas Jefferson was losing its hold on national politics. Old fissures in the party deepened, leading it to split into four factions, with the more conservative (strict constructionist) elements falling behind William Harris Crawford (1772–1834) of Georgia. This faction, known contemporarily as Crawford Republicans, had the support of the “Virginia dynasty”—Presidents Jefferson, Madison, and James Monroe—but ongoing concerns about Crawford’s health undermined efforts to consolidate the party under his aegis. A second wing came from a rising star, Andrew Jackson (1767–1845), the great military hero of the War of 1812 who at that time was senator from Tennessee. Into Jackson’s fold fell especially rural and Western elements that were growing in size and influence. These were the Jackson Republicans, who later would become the Democrats. The third group was the John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) wing, based heavily in the old Federalist area of New England and composed of elements that generally favored a more activist government and federal spending on internal improvements. Henry Clay (1777–1852) of Kentucky led a fourth Western faction that embraced the “American System,” an economic plan rooted in the “American School” ideas of Alexander Hamilton. The powerful Kentuckian, then Speaker of the House, favored the preservation of the Bank of the United States and the development of a system of internal improvements that would bind the nation together.6

Amid the ebb and flow of these competing and realigning interests, Joseph Hemphill (1770–1842), a former lawyer and judge serving as a representative from Pennsylvania, first introduced a bill in 1822 to authorize general surveys of proposed transportation improvements. With President Monroe still fully ascendent and the Democratic-Republican Party sufficiently united, the General Survey bill went nowhere in either 1822 or 1823. However, by 1824, the ground had shifted considerably. Hemphill, reelected to the Eighteenth Congress (March 1823–March 1825) as a Jackson Federalist, had new friends and allies. Chief among these were a powerful cabal of Jackson Republicans and a significant number of well-placed Adams-Clay Federalists including of course House Speaker Henry Clay. Standing in opposition was a vocal and steadfast group of Crawford Republicans, most of whom later migrated to the Jacksonian wing of the party but who retained, out of loyalty or long habit, the small government predilections of the old Jeffersonian party.

A painting of Henry Clay by J. W. Dodge, 1843

Library of Congress

A lithograph of Andrew Jackson

Library of Congress

Each of the five who rose in opposition to the bill hailed from Virginia, but so did the first and most eloquent advocate: James Barbour (1775–1842), a former governor of that state who allied himself with Adams and would later serve as his secretary of war (1825–1828). After referencing the usual “necessary and proper” arguments related to post roads (the roads built and maintained for mail delivery between major cities), Barbour expressed a more novel opinion that road construction was justified by the congressional power “to provide and maintain armies and navies,” as these “must be filled with troops, cannon, small arms, and all the munitions of war” and that “the means of transporting these are just as necessary as the forts themselves.”7 This argument especially may have resonated with the several veterans of the War of 1812 who later spoke on the topic, all of whom— including Barbour’s cousin John Strode Barbour (1790–1855), also of Virginia— favored the legislation.8 Taking up a banner for his Western allies, James Barbour called back to the recent war and the actions of a selection of New England states at the infamous Hartford Convention (1814–1815) which, acting in the name of states’ rights, had embraced secessionism and moved “to abandon the service of the United States, at the very moment a powerful foe was endeavoring to devastate our northern frontier, and to whelm it in the horrors of war.” He then contrasted those actions with the “people of the West,” who threw aside thoughts of constitutional restrictions and state’s rights and rallied together under Andrew Jackson to victory at the Battle of New Orleans. “They sought the foe, they fought and conquered him; triumph sat upon their brow, and the joy of victory gladdened a nation’s heart. A practical illustration is here presented of these two systems of Constitutional Construction.”9

Yet another Virginian, George Tucker (1775–1861), a Crawford Republican elected to the Eighteenth Congress, spoke for those in opposition and threw out a host of arguments. He pointed to Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution, which “prohibits Congress from making any discrimination in favor of the ports of a state, over those of another.” This was the states’ rights position that underpinned most opposition arguments—that major internal improvement projects would provide outsized benefits for some states at the expense of others and thus would represent an unjust transfer of wealth. He then brusquely tossed aside Barbour’s military justification: “we have raised and supported armies in two wars, without making roads and canals.”10 Tucker also feared the inevitable graft that would result from the millions of dollars required for internal improvement, as “the city [of Washington, D.C.] will swarm with hundreds of projectors, and their maps and plans, beautifully illuminated, electioneering for business; and as they would succeed according to their address, and means of conciliating favor, the result would be that we should have roads without travelers, and canals without navigation, and perhaps without water.”11 Lastly, Tucker, with a flair for humor, dismissed another proffered argument that constitutional authority to “establish post offices and post roads” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 7) could provide a basis for broader authority to build roads or bridges. “Our whole territory is intersected with roads, and there is not, perhaps, a square of three miles in the United States, having a population of ten persons on it, in which there is not a road sufficient for the transportation of the mail. Nothing,” he continued, “can be more unnecessary than such a power to Congress.”12

A Kentuck ia n joined Barbour in supporting the bill and defending Western interests. An Adams-Clay Republican with a keen wit, Richard Aylett Buckner (1763–1847) went after the states’ rights argument and picked it apart at its core. “If this government shall ever so far lose sight of its true principles, as to aim at the downfall of state’s rights, it will not commence the perpetration of so wicked and nefarious a design, by exhausting its funds in improving, beautifying, and strengthening the states.”13 Buckner then assumed a more serious tone and spoke of the need for “forming additional ligaments by which to unite us.” Internal improvements including roads and river work were justified, as he argued in a moment of prescience, because “a separation of the states [secession] is an evil not only more probable, but even more to be deprecated than a consolidation of power; and if ever the predictions of our downfall by the enemies of Republics shall be realized, it is to be the result of a separation produced by sectional feelings and jealousies.”14 Buckner noted in closing that “I am aware that less has been done for the West than for any other portion of the Union, yet,” he offered, “we shall not complain.”15

John Randolph (1773–1833) of Virginia closed out the debate on February 10. He was a founding member of the “Old Republicans,” a conservative wing of the Democratic-Republican Party that sought to restrict the role of the federal government. By 1824, he stood with the Crawford Republicans in opposition to the General Survey bill based on constitutional scruples. It was his stated conviction “that Congress did not possess the power, by the Constitution, to engage in a system of internal improvements, as contemplated in this bill.”16 For him, it was enough that its advocates had failed to consolidate their “necessary and proper” arguments. “One gentleman is fully persuaded that it is contained in the power to establish post offices and post roads. Another disclaims this ground entirely; but sees it clearly in the power to regulate commerce. Another rejects this as altogether untenable; but discovers it, as clear as the noon day’s sun, in the power to declare war. . . . If that power is given,” he concluded, “why do not gentlemen agree in what part of the Constitution it is to be found?”17 The House considered and rejected a series of amendments before ending debate with a procedural vote that saw advocates secure a third reading of the bill with 115 “yeas” to 86 “nays.” That result shed light on the size and shape of an emerging majority support in Congress for a robust internal improvement program.18

An engraving of John Randolph by John Sartain

Library of Congress

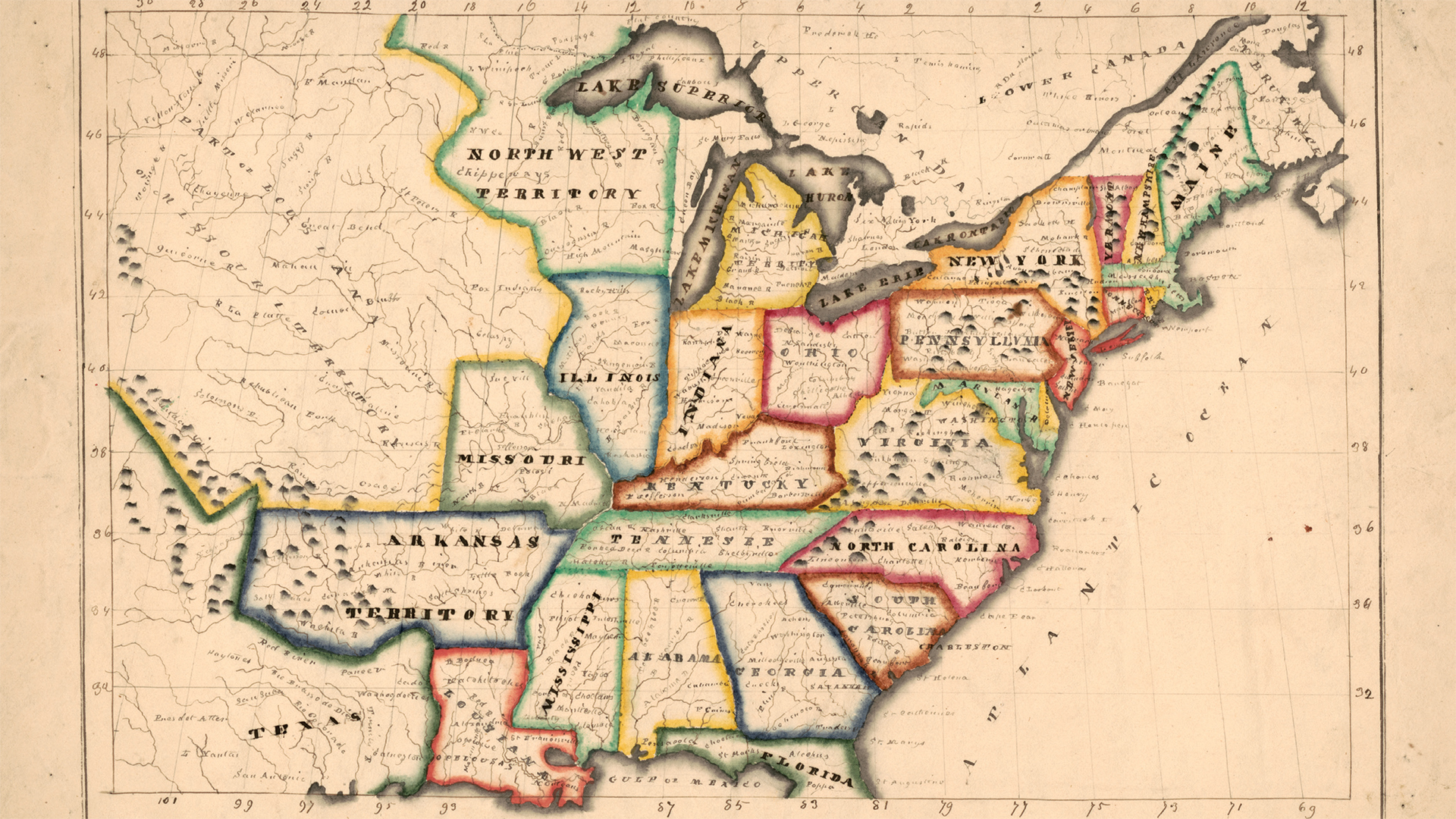

Analysis of that vote by state provides early evidence to the growing heft and weight of the Western vote. The new Midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and Ohio favored the measure 28–0; and the Deep Southern states of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi voted 7–0 for the measure. The much more populous seaboard states in both North and South opposed the bill with 79 “yeas” and 86 “nays.” Breaking in opposite directions, the two most populous states in the country decided the vote. New York alone provided more than a quarter of all opposition votes at 24 but lost 7 to the other side; it was Pennsylvania that pushed the procedural vote over the top, generating 23 votes in favor and losing only 2 to the opposition. The State of New York was just completing the Erie Canal—an entirely state-funded endeavor—which would create access to the Great Lakes and to the rich farmland and mineral and timber resources west of the Appalachians and make New York the preeminent commercial city in the United States. It understandably loathed to risk its hard-earned advantage in transportation by subsidizing its competition. Pennsylvania was otherwise motivated. With Philadelphia and its busy ocean port at one end of the state, Pittsburgh at the mouth of the Ohio River on the other, and 300 miles and a stretch of the Appalachians separating the two, the state had a rich stake in developing its roads and rivers and would need federal largesse to compete with the Erie Canal.

Analysis of that same procedural vote by party points to the final splintering of the Democratic-Republicans and to the birthing of a Jacksonian party with Western roots. Jacksonians alone, counting both the Republican and Federalist factions, provided sixty votes in favor of the bill, which amounted to more than half of the total. They were joined in an alliance of convenience by a splintered Adams- Clay faction that divided almost evenly between “yea” and “nay” votes. Those from Kentucky and Ohio supported the bill in large numbers, whereas all thirty-one opposition votes generated by Adams-Clay Republicans came from Eastern Seaboard states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont). The Crawford Republicans provided nearly half of the opposition number. This vote, coming as it did on February 10, evidenced sufficient support for passage of the bill through the House of Representatives, though obstacles remained in the Senate. There also were indications that President Monroe, like his predecessor James Madison, harbored concerns about the constitutionality of these internal improvement bills. Speaker Clay held off for several weeks on a final vote, and by the time he returned to it in late April, much had changed in his favor.

During that interregnum, the U.S. Supreme Court took up the issue of internal improvements and promised a resolution as to its constitutionality, one way or the other. The case before the court was a New York law dating to 1798 granting Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston—two titans in the development of the steamboat—a state monopoly on “navigating all boats that might be propelled by steam, on all waters within the territory, or jurisdiction of the state [of New York], for a term of twenty years.”19 The two men subsequently sold an operating license to Aaron Ogden, a former New Jersey governor, who proceeded to run a steamboat between Elizabethtown, New Jersey, and New York City. Several years later, in 1818, he was joined on that route by Thomas Gibbons, who had been licensed separately by the U.S. Congress under a 1793 law regulating coastal trade. Ogden filed a complaint with the Court Chancery of New York and won an injunction to stymie any competition from Gibbons. The latter secured legal counsel and appealed the decision. His lawyer, Daniel Webster (1782–1852), had been the winning attorney on the McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) case and was an increasingly prominent representative from Massachusetts then serving on the House Judiciary Committee.20

An engraving of Aaron Ogden by A. B. Durand, ca. 1834

Library of Congress

The case was litigated all the way to the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice John Marshall (1755–1835) ultimately ruled on behalf of Gibbons in carrying out the clear intent of the Constitution to have Congress, rather than individual states, regulate interstate commerce as well as intrastate commerce that substantially impacts interstate commerce. The landmark ruling in Gibbons v. Ogden empowered the federal government, through the Commerce Clause only, to conduct internal improvements of a national character. Advocates for the legislation pending in Congress took the win and moved quickly and successfully to pass legislation in late April. 21

The Annals of Congress (1789–1824), a precursor to the modern Congressional Record, references the General Survey Act one last time in its Appendix under “Public Acts of Congress,” which presents the text of the act in its entirety.22 Dated 30 April 1824, the new law authorized the president “to cause the necessary surveys, plans, and estimates, to be made of the routes of such roads and canals as he may deem of national importance, in a commercial or military point of view, or necessary for the transportation of public mail.” The second section approved funding of $30,000 and authorized the employ of “two or more skilful [sic] civil engineers, and such officers of the Corps of Engineers.”23 Though the approved funding was a relative pittance, the Army engineers ultimately proved their worth through the planning and coordination of transportation projects, and the act heralded the beginning of a great national program of internal improvements.24

Fresh from victory on both legal and legislative fronts, Clay and his Western allies returned to Congress with a bill to fund navigation improvements on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. They carried it to the floor of the House of Representatives on 7 May and opened the discussion the following morning, a Saturday. Speaker Clay tasked fellow Kentuckian, Robert Pryor Henry (1788–1826), with making the case for improving “Western Rivers.” Henry had been born in Scott County, Kentucky (then part of Virginia), and took a degree in classical studies from Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, before studying law and gaining admittance to the bar in 1809. He served in the War of 1812 and was elected to the Eighteenth Congress as a Jackson Republican. After establishing himself as “a friend of State sovereignty,” he indirectly referenced both the Gibbons v. Ogden ruling and the General Survey Act in assuming it “to be the settled rule of the government that Congress have the power to do what is proposed to be done by the bill under consideration.” The question at hand, then, “shall be directed throughout, to the naked questions of expediency, necessity, practicality, and propriety.” Henry called out first for fairness and equity. “Whilst so much has been done, and is still doing, for the benefit of the seaboard, may we not insist that it is high time to do something for us?” Then, in a direct emotional appeal, he put it to “the magnanimity and justice of our Atlantic brethren to say whether they will not protect our agriculture and our internal commerce against the bars, the sawyers, the planters, the snags, those stationary pirates of the Ohio and Mississippi?” He finally recalled the “loss of the steamboat Tennessee, a disaster which is hardly surpassed in the annals of shipwreck!” That disaster, he hoped, “will beget a lively attention to this great concern.”25

A map of the United States by A . T. Perkins, ca. 1824

Library of Congress

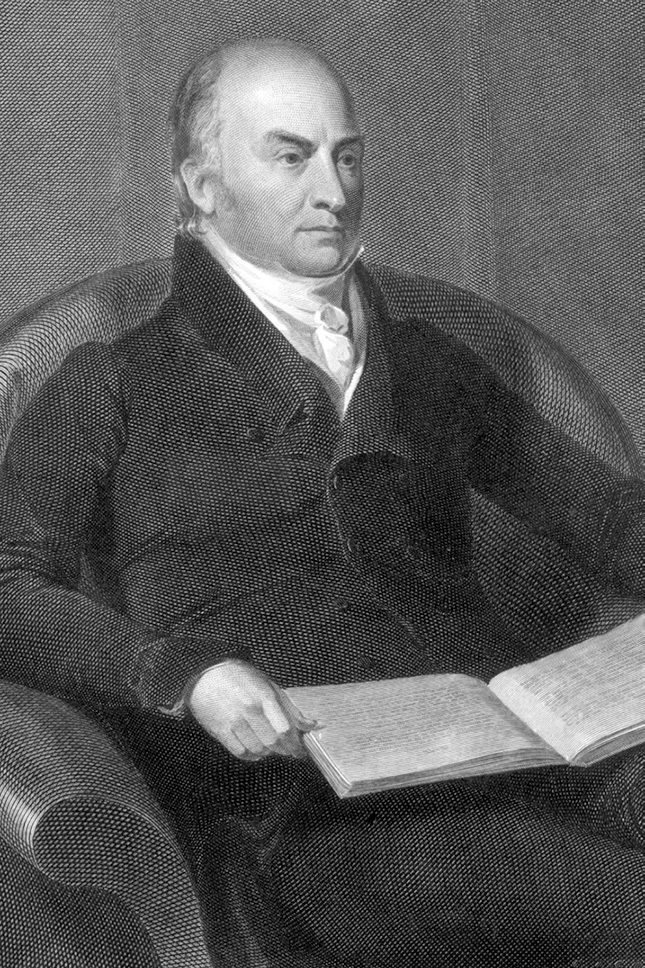

Representative Andrew Stewart (1791– 1872) of western Pennsylvania, reelected as a Jackson Republican, rose in favor of the bill and promptly referenced the 1822 Bernard and Totten report. He drew particular attention to the section detailing the “losses sustained at present by those who navigate the rivers Ohio and Mississippi, [which] were estimated as high as from five to ten percent.” These losses, “when it was recollected that the commerce with Pittsburgh alone amounted to a million and a half of dollars,” were enormously costly and would “justify a much larger expenditure than is now proposed.”26 The House passed the bill four days later on 11 May, and it went to the Senate. There it was introduced to the floor on 19 May by Kentucky Senator Richard Mentor Johnson (1780–1850), another Jackson Republican and a future vice president under Martin van Buren. Johnson also referenced the Army report, “which is now before us. . . . It is the opinions of the most scientific and experienced engineers” that the “causes which render our navigation dangerous” may be “removed at an expense quite inconsiderable, compared with the advantages that would ensue.”27 Senator Thomas Hart Benton (1782–1858), the famed champion of westward expansion and, later, Manifest Destiny, failed in a last-minute bid to incorporate the Missouri River into the legislation.28 The Senate subsequently approved what would be the first rivers and harbors bill, and it became law on 24 May 1824.29 The act authorized the relatively paltry sum of $75,000 for work on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, but John Quincy Adams’s election later that year put a strong advocate of internal improvements in the White House. His inaugural address in March 1825 welcomed “progress [that] has been made in the defense of the country by fortifications and . . . by scientific researches and surveys for the further application of our national resources to the internal improvement of our country.”30

An engraving of President John Quincy Adams by A. B. Durand, ca. 1826

Library of Congress

The significance of these two bills, each of which celebrates a bicentennial in 2024, scarcely can be overstated. The General Survey Act empowered the Army to chart transportation improvements vital to the nation’s military security and commercial growth while authorizing Army engineers to design canals, railroads, and both state and private roads. The initial appropriation of $30,000 grew to a total of $425,000 by 1837 and saw the Corps, with few restrictions, undertake surveys and plan internal improvements in virtually every corner of the growing nation.31 The first rivers and harbors act was an obvious concession to Western interests and an overdue recognition of the vital importance of maintaining navigable waterways for commerce and transportation. Congress followed it up two years later with a second rivers and harbors act that combined authorizations for both surveys and projects and established a pattern that pushed spending over the next 100 years to more than $1 billion on thousands of rivers and harbors projects in every state.32 In the early application of those laws, a major portion of the field work fell to the topographers who set out to develop a working system of internal improvements and, a decade or so later, to foster the establishment of an independent Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1838. Twenty-five-years later, during the U.S. Civil War, Congress merged the two engineer corps, and they thereafter worked in unison to develop the modern civil works program.

A lithograph of Maiden Rock on the Mississippi River, published by Currier & Ives, ca. 1850

Library of Congress

Notes

1. “Melancholy Catastrophe,” Poughkeepsie Journal, 19 Mar 1823, 3; James T. Lloyd, “Sinking of the Steamer Tennessee,” in Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory and Disasters on the Western Waters (Cincinnati, OH: James T. Lloyd, 1856), 61–63; House of Representatives, “Ohio and Mississippi Rivers,” 28 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of the Congress of the United States (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1824) (hereinafter Annals of Congress), 1704; House of Representatives, “Navigation of Western Rivers,” 8 May 1824, vol. 42, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 2582

2. Third System coastal fortifications were authorized in response to lessons learned in the War of 1812. The Army Corps of Engineers ultimately built dozens of such forts between 1816–1867. These include Fort Pulaski in Savannah, Georgia; Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina; and Fort Warren in Boston, Massachusetts. First System coastal defenses were built at the end of the Revolutionary War, and Second System defenses were built just before the War of 1812. Frank N. Schubert, The Nation Builders: A Sesquicentennial History of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, 1838–1863 (Fort Belvoir, VA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, 1988), 5; Todd Shallat, “Building Waterways, 1802–1861: Science and the United States Army in Early Public Works,” Technology and Culture 31, no. 1 (Jan 1990): 18–50.

3. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8.

4. McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 4 (1819). https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/mcculloch-v-maryland.

5. Matthew T. Pearcy, “The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Evolution of Navigation Practice and Policy, 1800–1865,” in Two Centuries of Experience in Water Resources Management: A Dutch-U.S. Retrospective, eds. John C. Lonnquest et al. (Alexandria, VA: IWR and Rijkswaterstaat, 2014), 51, 56–60.

6. Calvin Colton, ed., The Private Correspondence of Henry Clay (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1855), 253.

7. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 3 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1328.

8. The War of 1812 veterans were Robert Pryor Henry (1788–1826), Charles Anderson Wickliffe (1788–1869), and John Strode Barbour (1790–1855). All three were Jackson Republicans.

9. James Barbour failed, however, to win over his brother, Philip Pendleton Barbour, a Crawford Republican and former Speaker of the House (17th Congress). Philip Barbour would later serve as an associate justice of the Supreme Court. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 3 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1331.

10. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 3 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1337.

11. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 3 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1341.

12. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 3 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1335.

13. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 4 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1362.

14. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 4 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1364.

15. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 4 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1394.

16. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 10 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1463.

17. House of Representatives, “Surveys for Roads and Canals,” 10 Feb 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 1465.

18. The “third reading” is a pro forma question that routinely is put and approved by voice vote just before the measure itself is put to a vote. If the question is put to a vote and decided in the negative, the bill is considered rejected. See “Reading, Passage, and Enactment,” House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House, 104th Cong., 2nd sess. (1 Jan 1996), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-HPRACTICE-104/pdf/GPO-HPRACTICE-104-45.pdf

19. Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824). https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/22/1

20. The 1819 Supreme Court case McCulloch v. Maryland helped to define the relationship between the federal government and the states, and the scope of Congressional powers. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Congress has implied powers, or “unenumerated” powers, under Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, also known as the “necessary and proper” clause. This clause gives Congress the power to establish a national bank, and to pass laws that are “necessary and proper” to carry out its duties.

21. Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824).

22. United States Congress. The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States; with an Appendix, Containing Important State Papers and Public Documents, and All the Laws of a Public Nature; with a Copious Index. [First To] Eighteenth Congress.—First Session: Comprising the Period from March 3, 1789 to May 27, 1824 (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1849).

23. House of Representatives, “Public Acts of Congress,” 30 Apr 1824, vol. 42, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 3217.

24. Schubert, Nation Builders, 10–11; Todd Shallat, “Building Waterways, 1802–1861: Science and the United States Army in the Early Public Works,” Technology and Culture 31, no. 1 (Jan 1990): 28–29.

25. House of Representatives, “Navigation of Western Rivers,” 8 May 1824, vol. 42, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 2579–80, 2582. See also the House report of the Committee on Roads and Canals, which pulls heavily from the Bernard and Totten Report and references the Tennessee: H. Rept. 18-75, Report of the Committee on Roads and Canals, upon the subject of the navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, accompanied with a bill to improve the navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, 18th Cong., 1st sess. (28 Feb 1824), 3, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/SERIALSET-00105_00_00-076-0075-0000

26. House of Representatives, “Navigation of Western Rivers,” 8 May 1824, vol. 42, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 2581.

27. Senate, “Mississippi and Ohio Rivers,” 7 May 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 762–65.

28. Senate, “Mississippi and Ohio Rivers,” 7 May 1824, vol. 41, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 764.

29. House of Representatives, “Public Acts of Congress,” 25 May 1824, vol. 42, 18th Cong., 1st sess., Annals of Congress, 3228.

30. John Quincy Adams, “Inaugural Address,” 4 Mar 1825, The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-25.

31. Forest G. Hill, Roads, Rails, and Waterways: Army Engineers and Early Transportation (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1957).

32. Christopher M. Klyza, “The United States, Natural Resources, and Political Development in the Nineteenth Century,” Polity 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2002): 8–9. See the valuable chart on page 9 of Klyza’s article for expenditures on rivers and harbors projects between 1821 and 1921.

Author

Dr. Matthew T. Pearcy has been a historian with the Army Corps of Engineers since 2001 and currently works in its Office of History in Alexandria, Virginia. He has published articles in Louisiana History, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Florida Historical Quarterly, Military History of the West, and several long articles in Army History related to Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys (1810–1883) and his Civil War exploits. He holds a PhD in history from the University of North Texas and is currently completing a Civil War biography of Humphreys.