A Bold Experiment

The U.S. Zone Constabulary in Occupied Germany, 1946–1952

By M. Ashley Vance

Article published on: August 1, 2024 in the Army History Fall 2024 issue

Read Time: < 56 mins

Constabulary forces demonstration, Memorial Day, May 1947 National Archives A U.S. Zone Constabulary shoulder sleeve insignia Fort Riley Museums

As the world paused to celebrate V-E Day in May 1945, Army commanders in Europe were implementing the postwar occupation of Germany, Operation Eclipse, to govern millions of Germans within a predesignated U.S. Zone of Occupation.1 Despite extensive planning in Washington, leaders in Germany faced a situation that required flexibility. General Lucius D. Clay, military governor of the Army’s occupation zone, later remarked that during the early occupation period, “Nobody had had any experience in this kind of job. . .. We had nothing. We had to improvise. We had to make decisions on the spot.”2Immediate issues included setting up a military government, managing an unpopular demobilization program, and securing rural areas while maintaining unit integrity. The first major initiative to solve the many problems was born out of the spirit of improvisation later voiced by General Clay. In fact, the solution fundamentally altered the nature of the postwar occupation.

The answer to the complications developing in occupied Germany was the creation of a highly mobile police force, the U.S. Zone Constabulary. The “troopers,” as Constabulary soldiers came to be known, maintained law and order, secured U.S. zonal borders, and supported the development of local German police forces. Upon its formation, Stars and Stripes described the police unit as “a bold experiment” and a “departure into a new military field of operations.”3Instead of a massive occupation force to secure all areas at once, small groups of Constabulary troopers spread out to conduct patrols. If a disturbance developed, the mobile force would quickly coalesce to resolve the issue. Later dubbed “the Army’s most unusual organization,” the Constabulary was “born on foreign soil” and “never set foot in its homeland.”4

At its height, the Constabulary never fielded more than 30,000 soldiers and existed only from July 1946 to December 1952.5 It would be easy, therefore, to discount the impact the police force had on the postwar occupation. The few publications that touch on the Constabulary examine its organizational narrative but do little to address the unit’s participation in the Army’s mission or its transformation from a punitive occupation force to a defensive shield for the Cold War.6This is understandable, especially considering contemporary and historical narratives of the occupation during the late 1940s. For example, in 1952, Combat Forces Journal referred to forces in Germany as “immersed in the pleasant round of garrison life.”7 As the story goes, occupation soldiers in Germany lived a relaxed, unimportant life that revolved around recreation and romantic relationships with German women. By the end of the decade, the occupation was no longer a serious affair because the Germans had taken the reins of local governance. More recent scholarship, such as Elaine Tyler May’s Homeward Bound and Susan Carruthers’s The Good Occupation, use the growing partnership with the Germans and the arrival of American dependents as a way to demonstrate the increased domesticity of Army forces in Germany during this period.8 However, these portrayals oversimplify the complex military and political situation in Europe and inflate the German capacity for self-government and security under a military occupation.

Beginning in early 1947, Army leaders in Germany responded to the deteriorating relationship with the Soviets. They reorganized occupation units for combat and developed a strict training regimen to prepare for a possible East-West confrontation. The stakes were all too real. In 1948, the Berlin blockade provided a glimpse into the Soviets’ commitment to secure their territory. By 1950, many worried that the outbreak of the Korean War was a Soviet feint to invade West Germany. For Constabulary troopers, the training was imperative, particularly for those posted at remote crossings along the East German and Czech borders. A historian at the time remarked that the threat of Soviet forces at the border “was not publicly appreciated until 1948, but . . . gave rise to trouble from the very beginning.”9 To be sure, soldiers in postwar Germany had a relaxed tour compared to those in combat, but they spent most of their time preparing for a war that, thankfully, never came. By the time the Korean War broke out in June 1950, troopers spent almost all their work week either in a training camp or out on a field maneuver. Few soldiers would have described their life in the field as pleasant, or as an equivalent to the supposedly easy, uncomplicated garrison life.

Although the shrunken force did not have the capability to stop the Soviets if they chose to invade, the intent to prepare for a possible invasion was ever present. That effort was just as important for the soldiers as it was for the Army’s public commitment to stand and defend the rebuilding nation. Yet, for all their accomplishments, the Constabulary as a unit is barely known today. As one writer aptly summarized, “It succeeded, but with virtually no recognition in the annals of U.S. military history.”10 Nevertheless, this small, short-lived police force helped secure a fragile peace and aided the creation of a training framework that Seventh Army later expanded and relied on for decades.

Redefining the Occupation

During the opening months of the postwar occupation, Army commanders in Germany wrestled with a massive campaign to demobilize and redeploy approximately 3 million soldiers out of Europe. Complicating matters, the War Department’s point-based approach to demobilization was highly problematic. The program assigned points for various attributes like time overseas, participation in battles, and number of dependents. Soldiers had to meet a point threshold before earning the right to go home.11 It was widely unpopular among soldiers because many saw the point system as an inaccurate reflection of who deserved to go home first. The result was low morale, bad behavior, and the decimation of unit efficiency.12 As one soldier awaiting his orders remarked, “Never was so little credit given to those to whom so much was due.”13 Frustration with the point system prevailed throughout the European Theater of Operations. A report later argued that something needed to be done to resolve the issues with demobilization because “the Army was literally falling apart at the seams.”14

War Department planners initially called for a postwar “Army Type Occupation” that deployed tens of thousands of soldiers across the U.S. Zone to establish a military government, enforce law and order, and maintain zonal security.15 However, a variety of evolving factors led commanders to reassess the utility of maintaining a large troop presence in occupied Germany.16 First, redeployment simplified into demobilization after Japan surrendered in August 1945. Second, the point-based system wreaked havoc on troop morale and unit efficiency. Third, the Germans did not resist the occupation, as the military planners had feared they would. Finally, the Army sought to separate the military’s tactical forces from the more administrative Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS), once it became operational.

Throughout summer and fall 1945, leaders at the War Department and within the newly formed U.S. Forces, European Theater (USFET), discussed alternatives to the large-scale deployment. Commanders reviewed reports from the field to identify problem areas and discover solutions. After action reports from 12th Army Group and Fifteenth Army were particularly relevant, as these forces led early occupation operations during the final six months of the war before Eclipse officially launched on V-E Day. Of note, Fifteenth Army G–5 (Civil Military Operations) units experienced acute manpower shortages during their wartime occupation. As combat divisions invaded and defeated more territory in Germany, existing G–5 staff stretched thin to cover the expanding front without additional personnel. In response, Army leaders created “Frontier Commands” that deployed their limited troops in mobile, patrolling units to police and secure areas simultaneously.17 The success of the Fron tier Commands inspired a new postwar organization. Planners embraced a concept that would use similarly mobile, dispersed units to control the U.S. occupation zone. Rather than an “Army-type” occupation, a new “police-type” occupation developed.

No one individual or organization can be credited with the idea to create the new, mobile police force. Instead, leaders agreed to establish a “super military force” to secure the zone with much fewer soldiers.18 But initial ideas varied. General George C. Marshall proposed to General Dwight D. Eisenhower a replication of the police occupation model being used in Japan, which used local Japanese police forces alongside the U.S. military to maintain law and order. General Eisenhower agreed, but refused to employ local police forces in Germany, as was happening in Japan. Considering Germany’s position as a former aggressor, public opinion in both the United States and Europe would have opposed the possibility of employing Germans to police anyone, let alone the hundreds of thousands of refugees and survivors of war and state violence.19 The Army, General Eisenhower argued, should fulfill the police role. General Clay explained the concept: “The idea was that if we were going to have any problems internally in Germany, we needed light, fast, armed, highly mobile troops that could be moved to where they were needed very rapidly. Since this did not fit in with any of our existing organizations, the logical development was . . . the constabulary.”20 After many conversations and compromises, Army commanders formed the U.S. Zone Constabulary as the bedrock of a newly envisioned police-type occupation in Germany.

For the Constabulary to manage the occupation zone with fewer soldiers, the unit needed to be highly mobile and effective in policing and security. Broadly construed, the police unit would maintain law and order within the U.S. Zone and would secure inter zonal and international borders. Regular activities included daily patrols, lightning raids to stop illegal activity, support for Counterintelligence Corps investigations, roadblocks throughout the zone and along its borders, and supervision over reestablishing local German police units.21 To accomplish these goals, the police force needed carefully selected, highly trained soldiers capable of operating independently. These soldiers had to be ready to handle a wide range of issues from petty crimes to black-market trading, illegal border crossings, and even physical violence, if it arose. The police officers would have authority over German civilians, displaced persons (DPs), any foreign national entering the zone, and fellow Allied soldiers, civilian employees, and dependents. General Eisenhower told the War Department the “police-type method of occupation offers the most logical, long-range solution to the problem of security coverage,” especially given that “combat troops are becoming stretched so thin as to be incapable of adequately assuring law and order.”22

In October 1945, General Eisenhower announced the formation of the U.S. Zone Constabulary. Its activation would occur on the same day, 1 July 1946, that wartime tactical troops would detach from military government operations. The force had a triangular formation of three brigades, each responsible for one German Land (state) within the U.S. Zone. Across nine regiments, the twenty-seven squadrons had 144 troops, with twenty to thirty soldiers per troop. Initial estimates projected one Constabulary police officer for every 450 Germans, or 38,000 troopers to police about 17 million Germans living in the zone.23 Underlying this structure, a strategic reserve would remain in place in case of emergency. The reserve would activate and provide tactical support for issues like a widespread rebellion against occupying forces or an enemy invasion. However, just as leaders improvised and adapted to bring the Constabulary into existence, they learned that the evolving international landscape would wash away these early plans. General Joseph T. McNarney, who took over as USFET commanding general when General Eisenhower became Army chief of staff, appointed Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon as the Constabulary’s first commanding general. From his appointment in early January 1946, General Harmon had six months to enlist, train, and deploy the new police unit.24

Transforming Warriors into "Soldier Policemen"

The idea to fill the new police force with carefully selected, highly trained soldiers proved more aspirational than practical. General Harmon used the existing personnel and units within Germany to create the new Constabulary, as replacements were in short supply. Because the demobilization point system prioritized soldiers with longer terms of service, most experienced soldiers already had left Germany. In spring 1946, the occupation soldiers were either fresh draftees inducted after V-E Day or those who had too few points to meet the point threshold. Making matters worse, in January 1946, the War Department reduced the length of basic training from seventeen to eight weeks to get personnel to Germany as quickly as possible, thus creating a situation where the Army was “using soldiers with approximately two months training to support [U.S.] foreign policy.”25 These young, inexperienced soldiers were, by necessity, the foundation of the new U.S. Zone Constabulary. Like the average wartime GI, the Army continued to meet personnel quotas with 18- and 19-year-old draftees.

Two groups of soldiers transferred into the Constabulary. First, in October 1945, Third and Seventh Army provided the 2d, 6th, and 15th Cavalry Groups, Mechanized, to form District Constabularies, the test bed for the zonal unit.26 Then, in spring 1946, troops of the 1st and 4th Armored Divisions, Third Army, transferred to the new police force in bulk. Third Army was an appropriate choice. The unit initially formed in 1918 for the post–World War I occupation of Germany’s Rhineland and later won acclaim for its contribution in the 1941 Louisiana Maneuvers.27 During the war, while under the leadership of the famed General George S. Patton, the Army was recognized for its march across France and action in the Battle of the Bulge.28 Armored divisions especially were prepared for the new police mission, as the units had both the equipment and training to move swiftly, in a wide range of vehicle types, through unknown territory.

One Third Army battalion commander, Lt. Col. Albin F. Irzyk, summarized the soldier response to the news of the unit’s transformation. He remarked, “at the outset, the mission seemed impossible, the challenges more than daunting.” The battalion had to divest equipment quickly, such as the tanks, half-tracks, and armored artillery that brought it glory during the war. Newly appointed commander of 1st Constabulary Brigade, Colonel Irzyk’s larger issue was the psychological change. “There had to be a different mindset,” he said. “No longer were the tactical troops warriors, fighters. Yes, they were still soldiers, but now they would have to learn to be soldier policemen.”29

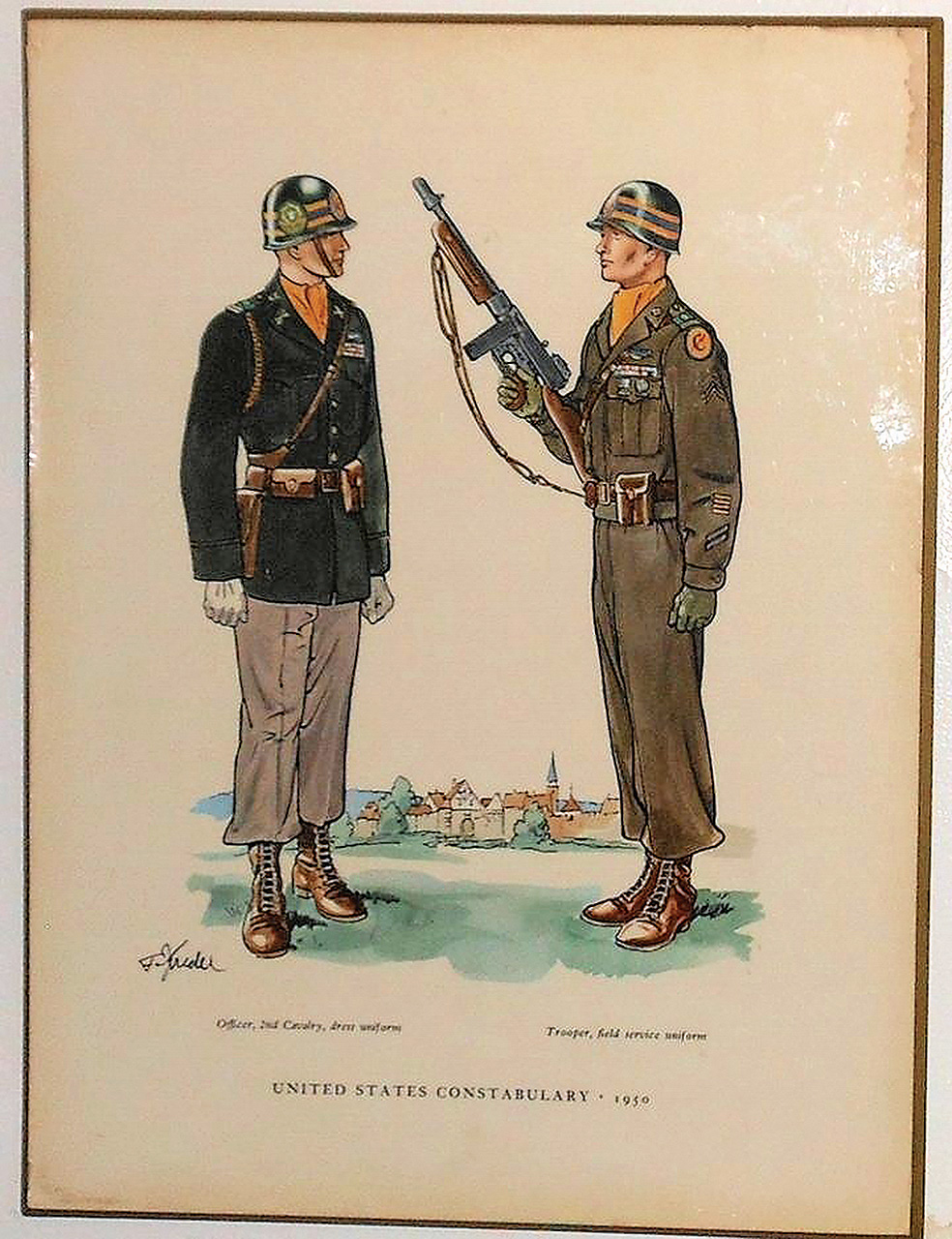

Part of the mindset shift included the development a new esprit de corps to set the occupation police force apart from its wartime predecessors. Constabulary leaders created a distinct motto, uniform, and colors to differentiate the troopers from other units. The motto “Mobility, Vigilance, and Justice” appropriately summed up the Constabulary’s goals and values. The uniform, once coined “the flashiest dressed . . . in Army history,” featured a striped helmet, yellow scarf, paratrooper boots, and a Sam Browne belt with leather pouches and side pistol.30 General Harmon later remarked, “the Constabulary uniform we came up with was a real eye-catcher.” The insignia, the letter “C” crossed with a lightning bolt, reflected the unit’s high speed and mobility. The colors, yellow, blue, and red, represented the amalgamation of the cavalry, infantry, and artillery, respectively. General Harmon recalled, “I saw to it that [the colors and insignia] were applied lavishly to every piece of our rolling equipment from my personal railroad train to our ubiquitous jeeps and motorcycles.”31 The distinctive insignia became “the symbol of law and order,” a “personification of American military strength,” and a “guarantee of justice and fair dealing.”32

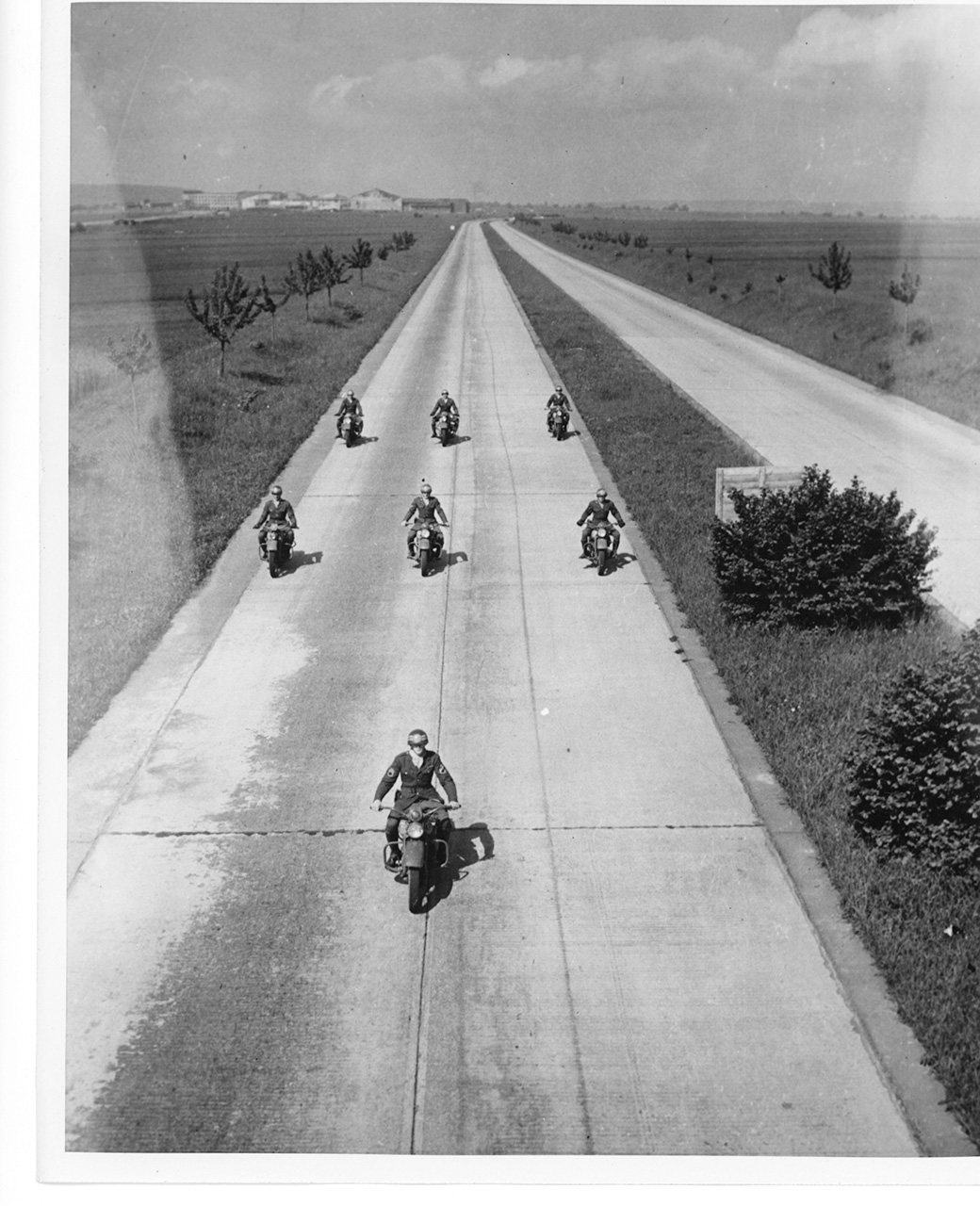

A motorcycle patrol near Moringen, Germany

National Archives

However, not all aspects of the new unit were postwar creations. At its core, the Constabulary was a reimagined cavalry unit and, as such, adopted both the organizational structure and terminology of its predecessor. Historically, cavalry forces organized into troops and referred to the soldiers as “troopers,” both of which the Constabulary adopted. Cavalry forces also had a history of border security and police functions going back to at least the 1913 Mexican Expedition.33 Although the Army generally had abandoned the use of horses, the U.S. Zone Constabulary relied on horses for remote and off-road patrols. During the planning stage, an Army commander casually described the equestrian police unit as akin to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or the Texas Rangers.34 Troopers quickly were dubbed the “Circle ‘C’ Cowboys.” The final cavalry connection came from the top. Through its seven-year history, each of the Constabulary’s four commanding generals previously led armored divisions before taking charge of the police force.

General Harmon inspects troops from the 1st Constabulary Brigade, Wiesbaden, Germany, July 1946.

National Archives

For the Constabulary concept to work, troopers needed to maintain high standards because they were “empowered with unusual authority in matters of arrest, search, and seizure.”35 To be successful, German civilians, DPs, other Army units, and Allied forces all needed to trust and rely on the troopers’ ability to act appropriately and fairly in a wide array of situations. To fulfill their mission to “maintain general security,” troopers had to be reliable, adaptable, and successful in building positive relations with local populations.36 As one Information Bulletin explained, “the nature of assignments makes it necessary that each trooper can function both individually and in a team in the dual role of soldier and special policeman.”37

An illustration of the U.S. Zone Constabulary uniform

Courtesy of usconstabulary.com

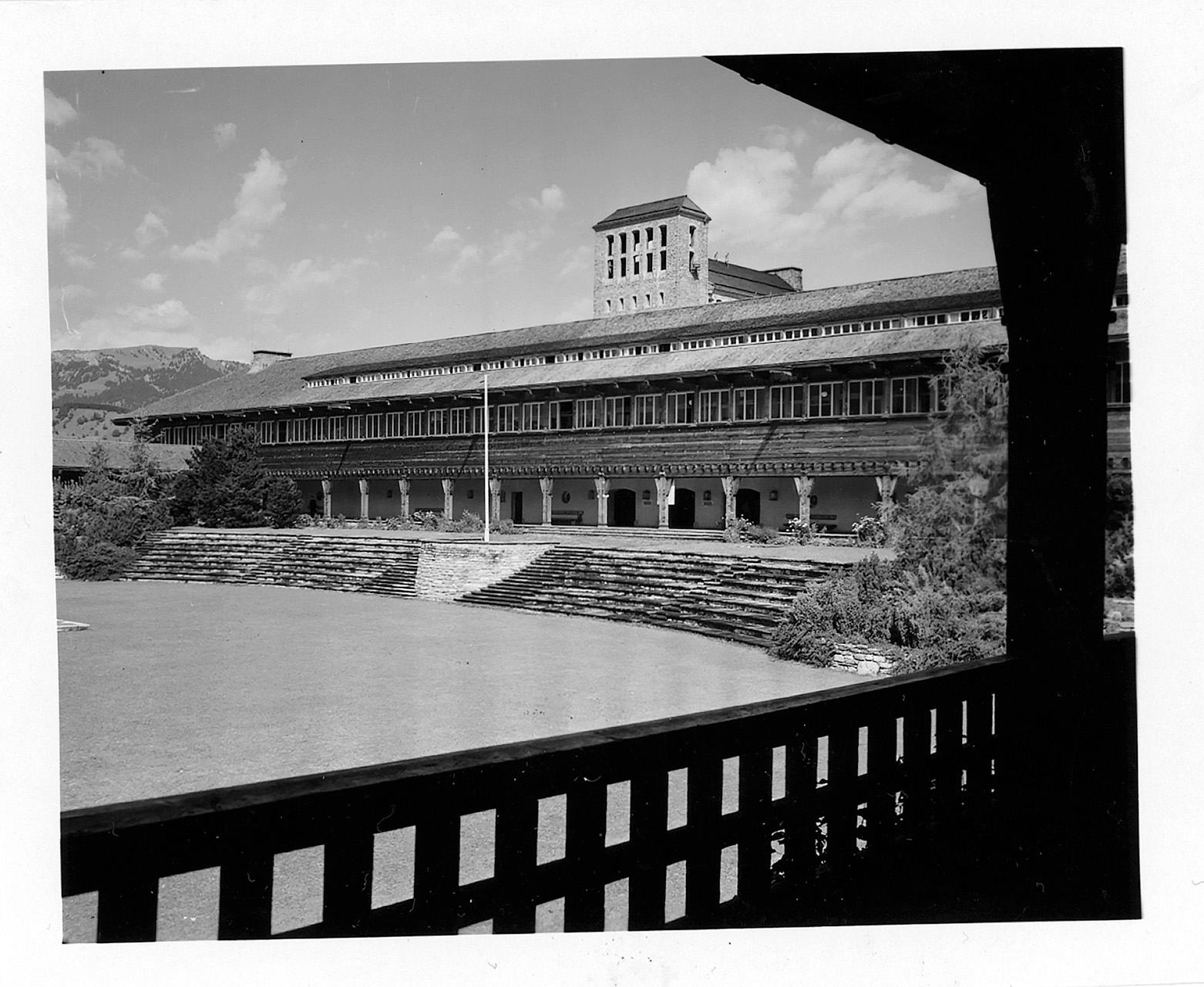

To prepare the Constabulary, USFET opened a special training school in Sonthofen, a small, remote town near the Austrian border in the southwest corner of the U.S. Zone. The Constabulary School opened in January 1946 to train officers and troopers on policies and procedures of the new organization. Soldiers referred to the school as the “West Point with the Dehydrated Curriculum” because courses, although wide-ranging, focused only on subjects pertinent to the police force.38Classes covered topics like “the history of Germany, occupational policy, courts and laws, the relationship of the Constabulary to military government and the German police . . . the mission of the Constabulary, police policy and procedures, tactics, general instruction, and communications.”39 Army leaders did not create a separate replacement training center because they hoped the Sonthofen school “could operate as a combi nation replacement and school center.”40 A plethora of training materials, including a hundred-page “Trooper’s Handbook,” were distributed to all Constabulary soldiers to quickly instill the values and high standards of the new police unit. The message to the troopers was simple: “There is no profession on earth which requires more strength of character than the police profession. . . . He represents the law and the dignity of the government he serves. . .. No class of officials can less afford to make mistakes than policemen.”41

Deploying the Police Force

The Constabulary’s activation on 1 July 1946 “marked a fundamental change in the concept of the occupation,” as a “police-type occupation force was considered more practical” than a large-scale deployment.42 The unit activated with 29,437 soldiers who were responsible for securing an area more than 43,000 square miles (about the size of Pennsylvania) with almost 1,400 miles of international and interzonal boundaries.43 To do so, the Constabulary conducted a variety of patrols. Tanks, jeeps, and motorcycles deployed to larger cities, horse and foot patrols traversed remote or mountainous areas, and air surveys covered unpopulated areas. The patrols had two key purposes. First, troopers traveled throughout their respective areas to monitor populations for subversive or illegal activities, conducting investigations and making arrests when needed. Second, patrols were intended to impress upon the German population “the military bearing and business-like manner” of the Army occupation.44 Patrolling quickly became the hallmark of the new police force. In the first six months of operations, troopers made 168,000 patrols (in vehicles, on horseback, and by foot) traveling more than 5 million miles. In the same period, Constabulary pilots flew more than 14,000 hours on 11,000 missions throughout the zone.45

The training grounds at the U.S. Zone Constabulary School, Sonthofen, Germany, August 1946

National Archives

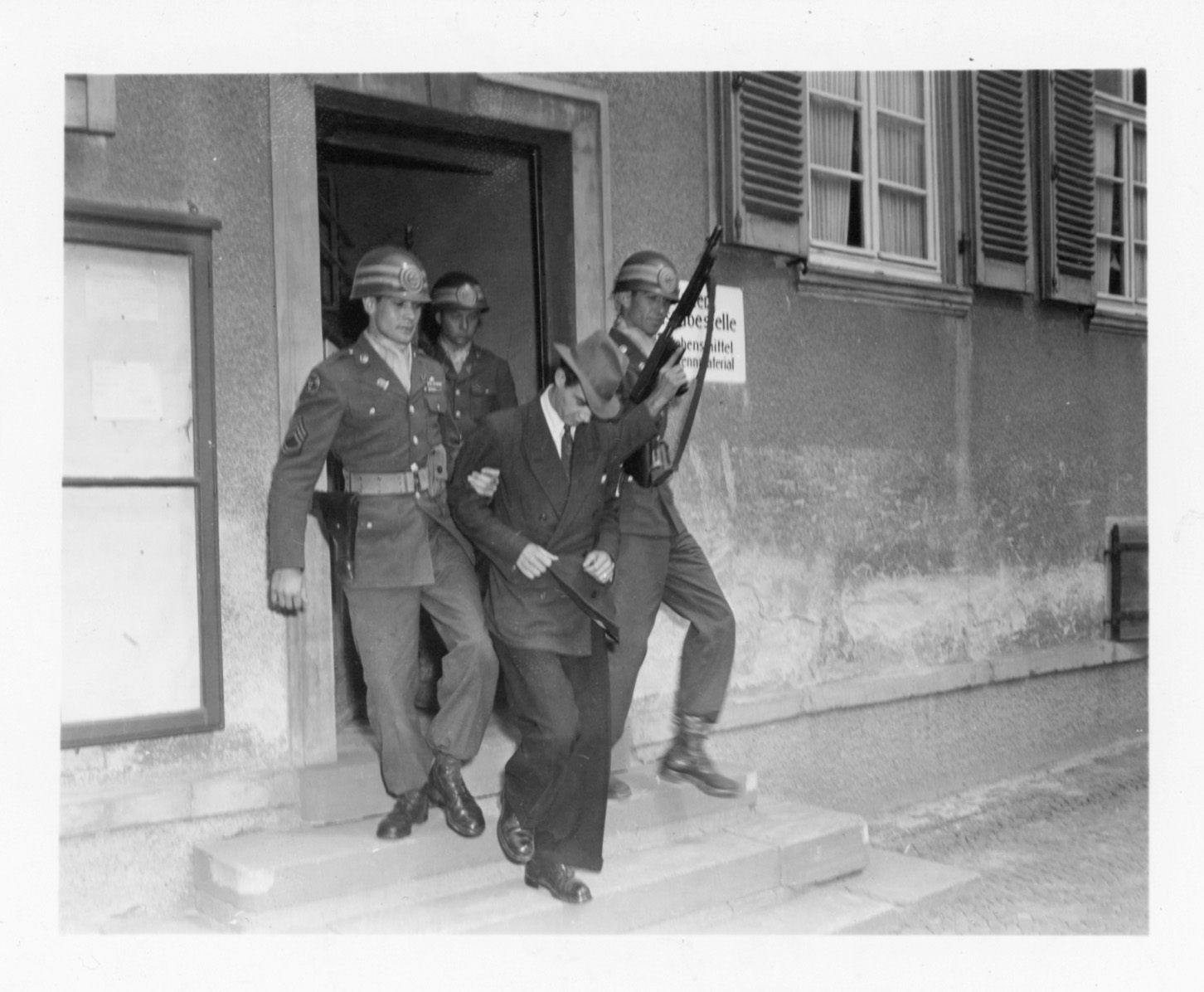

Patrol teams often consisted of three troopers and at least one local police officer. The partnership helped build the relationship with occupied populations, provided necessary German language translation, and trained local police forces. Generally, if the person under investigation was a DP or a German, the German officer conducted the interview or made the arrest. If the individual was an Allied soldier, civilian, or dependent, the Constabulary trooper took the lead.46 For example, in one investigation a patrol team from the 25th Constabulary Squadron and three German police officers searched the home of a German civilian suspected of illegally owning weapons. The inspection uncovered a single empty pistol holster and an Army-issued undershirt. Upon questioning, the civilian explained that the gun that had been in the holster already had been surrendered to Military Government officials. The German police officers arrested the suspect for possession of the holster and the stolen clothing and turned him over to the Army detachment at Vohenstrauss.47 The Constabulary’s long-term goal was eventually to function only in a supportive role to trained German police forces.

The Constabulary’s second major focus was border security. Troopers acted as “customs inspection, passport control, and general law enforcement” along the internal and international zonal borders.48 Early in the occupation, the borders between the zones were rather fluid. However, as the Cold War developed, militaries on both sides increased efforts to restrict interzonal movement. A 1947 report explained, “Dealings with Russians in matters concerning border control . . . have long been a problem owing to the apparent administrative friction in Soviet channels.” As a result, “Control of the Russian boundary is still unsatisfactory . . . because of the volume of illegal border crossing arrests.” The deteriorating situation along the border occasionally became deadly. The same report noted that in one incident, “an illegal border crosser, as an alternative to repatriation, murdered his U.S. Constabulary guard and then committed suicide.”49 As Soviet policies became more restrictive, more people attempted to illegally cross into the western zones. In one week in early January 1948, 79 people were arrested and another 335 were turned back. All but five came from the eastern zone.50 That figure was lower than summer months, as winter weather conditions tended to slow crossing attempts.

Members of the 16th Constabulary Squadron show an armored vehicle to local German children near Berlin, March 1949.

National Archives

Like the patrols, German police officers often accompanied Constabulary troopers at the border.51 But, as an occupied nation, German officers had no legal right to detain or arrest certain groups. Over time, Constabulary units slowly turned border duties over to German police, but the troopers had to provide administrative and tactical support at all crossing points. By 1948, the local officers were empowered to conduct “baggage and credential checking” for all crossers except military and Allied civilian personnel.52 When possible, the illegal crossers were turned away at the border, which German police forces could do. However, if the individual was a member of the Soviet or Czech militaries, troopers arrested them and informed European Command (EUCOM) headquarters of their presence.53

A third feature was unannounced raids, often called “swoop raids” or “lightning raids,” to discover illegal activities and contraband. Germans often referred to the Constabulary as the Blitzpolizei (lightning police) because of these raids. The surprise inspections took place in private homes, businesses, and DP camps. Raids occurred frequently to great effect. In the Constabulary’s first six months, seventy-one operations resulted in the arrest of 793 Germans and 502 DPs.54 A classic DP raid was Operation Camel, which took place on 25 November 1946 and involved 676 troopers. Army commanders ordered the raid because they suspected black-market activity was occurring in a DP camp. Just after 0430, members of the 27th Constabulary Squadron surrounded the Ulana Kaserne, a barracks for Polish DPs. Troopers quietly moved in while everyone slept and blocked all exits of the multi-floor building to prevent inhabitants from moving between floors or escaping. Then, troopers from the 10th and 13th Constabulary Squadrons began to clear the building, room by room, waking everyone in the process. The raid was very successful. In addition to a stash of ammunition, knives, black powder, and military uniforms, troopers seized more than $52,000 (roughly $710,000 in 2023 dollars) worth of codeine, morphine, and penicillin. In the end, troopers apprehended and interrogated more than a hundred people and arrested eighty-four of them.55 Given the youth and inexperience of some troopers, raids sometimes became a source of friction between locals and their occupiers. For example, at 0630 on 2 March 1948, troopers conducted a raid at the Eschwege DP Camp near Frankfurt, where 2,100 Jewish DPs lived and worked.56 The inspection revealed unregistered livestock, agricultural goods, and other items. Troopers arrested 103 residents and caused immense damage throughout the camp. International Refugee Organization area director U. P. Jonckheere sent a formal complaint to Constabulary commander Maj. Gen. Withers A. Burress and EUCOM Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner. Jonckheere argued that troopers and accompanying German police officers intentionally inflicted widespread damage in every building. In just in the administrative office, “doors, desks, cupboards had been deliberately forced open and damaged; chairs broken; all the records . . . were thrown all over the place.” He concluded, “There is no question that the Army had the right to pull a raid on a camp at any time, but . . . if a little patience had been shown, and time given for the keys to be produced, damage to doors etc. could have been avoided, and probably the troops would not have acted like maniacs.”57 The complaint prompted a series of investigations and increased troop inspections to curb unruly soldier behavior.

Frequent troop inspections were often the best way of keeping discipline and order among Constabulary units, particularly because many troopers were stationed so far apart from one another. General Harmon explained, “the Constabulary was peculiarly dependent upon the good judgment, sensitivity, and honesty of the individual trooper” because the troopers operated in remote areas away from their headquarters.58 To maintain strict standards, the general later remarked, “I set myself the task of visiting each of the twenty-seven squadrons at least once a month.”59 General Harmon also told soldiers that they were forbidden from airing grievances in the Stars and Stripes “B Bag,” a column dedicated to soldier gripes. Instead, he told troopers, “If you have a problem with a superior, you can write me personally and I will investigate.” After a soldier in Karlsruhe disobeyed that order, “I rearranged my schedule and went down to Karlsruhe in person.” General Harmon ordered a parade formation of the unit and “in the presence of his comrades, I took off the man’s insignia and dismissed him from the Constabulary.”60 Regular inspections ranged from the squadron commander to the military governor. General Clay frequently visited troops and inspected barracks to monitor behavior and morale.61

Three members of the Constabulary arrest a black marketeer at his home in Bad Homburg, Germany, August 1946.

National Archives

In addition to the patrols, border security, and raids, Constabulary troopers participated in a range of activities throughout the occupation zone. The police unit actively supported German Youth Activities program, holding events and fundraising throughout the year. During the 1947 holiday season, for example, one troop pooled funds and distributed candy to 1,400 schoolchildren.62 Other troopers, like Sgt. William Luddy, used their German language skills to give afternoon lectures to German children “on American ideology and history” to “teach the Germans the principles of self-government and democracy.”63 Constabulary troopers also offered suggestions to EUCOM leaders on how to modify existing policies. One 1947 report explained, “as a result of operational experience by Constabulary units in the field, a more effective method of controlling Displaced Persons was evolved.” The report went on to note that, rather than managing the civilians solely through raids, a new system of security controls at entrances to the camps, “proved successful as the number of serious incidents involving Displaced Persons dropped.”64

EUCOM also relied on the Constabulary to conduct covert operations. In spring 1948, troopers carried out Operation Finite, a five-day, top-secret mission to transport an immense cache of American-printed deutsche marks from Hamburg to Frankfurt for the trizonal currency conversion, Operation Bird Dog.65 On 20 June 1948, without prior public notice, the military governments in the U.S., British, and French zones replaced the devalued reichsmark with the new deutsche mark.66 The currency conversion in the recently merged western zones stabilized the German economy and quickly eliminated the high demand for black-market trading. It was made possible because the Constabulary successfully, and secretly, distributed the new funds to local finance offices throughout the occupation zone.

German children play with an American football during an event sponsored by the Constabulary forces.

National Archives

Operational Lessons and Early Adjustments

Within weeks of activation, commanders adapted daily operations and broader strategic goals based on early lessons learned. One of the first lessons was that small-scale operations testing could not be scaled up easily. Before the Constabulary activated, commanders experimented with two District Constabularies to test the possibility of deploying all units to patrol the entire zone simultaneously. Importantly, this testing did not include border security—it focused on policing.67 On the district level, a blanket-coverage approach worked. However, to cover the entire U.S. Zone, patrols and border security could not be conducted concurrently because there was not enough personnel and equipment. Leaders modified the original plan to use smaller, more mobile detachments on a rotating patrol schedule, both along the border and in towns. Instead of providing simultaneous coverage across the entire zone, units deployed in sizes that were commensurate with the population totals in their respective areas. Along the borders, checkpoints and roadblocks changed from static to mobile posts to remain unpredictable for potential border crossers and to use personnel more efficiently. The units “would establish a roadblock in a seemingly random location; inspect personnel and vehicles for a period of time, then move to a new location.”68

Throughout fall 1946, USFET leaders and General Harmon made more adjustments to the Constabulary. In September, the Army reduced or cut small detachments that they could not justify. In planning for winter, General Harmon ordered a pause to most secondary-road patrolling to regain control of some disorderly units and reduce gasoline consumption. In November, the Constabularies “show of force” tank parades reduced to only critical cities with higher crime rates and border patrols focused on areas where illegal crossings occurred most often.69 Population size no longer figured as a primary factor dictating patrol schedules. Additionally, War Department changes to USFET personnel levels drove many of the early adjustments. When the Constabulary activated, the Army assigned approximately 330,000 soldiers to Germany. By mid-1947, the approved total dropped to 117,000 soldiers, and by mid-1948 that figure reduced again to a mere 80,000 soldiers.70 Although these figures appear large for a zonal area about the size of Pennsylvania, they encompassed all staff within OMGUS headquarters and support services. Of the total personnel, less than half were tactical units charged with policing or securing the zone. The Constabulary never had more than 29,000 officers, despite the initial authorization for 9,000 more.71 Interestingly, by fall 1948, the 1st Infantry Division, the sole remaining tactical unit, maintained more soldiers than it had during the war, with 18,751 soldiers in three regiments.72 Despite the division’s overstrength, only around 40,000 soldiers were responsible to secure and police a densely populated occupation zone that contained about 230,000 DPs and 17 million Germans.73 Those numbers became more disproportionate over time as the German population in western zones increased.74 In practice, many units were staffed with a skeleton crew or only existed on paper at a time when relations with the Soviet Union worsened weekly.

Planning for the Constabulary was based on the expectation that a strategic or tactical reserve would support the police force in case of an emergency.75 Ideally, a strategic reserve could deploy across the entire zone if hostilities arose with an enemy nation and a tactical reserve could support local crises like a widespread rebellion or a dramatic increase in violence. However, those goals were abandoned almost immediately. When the Constabulary activated in summer 1946, Third Army was the sole remaining army in the occupation zone, as the others already had inactivated. Months later, Third Army inactivated and “there was no strategic or tactical reserve other than that maintained within the organization of U.S. Constabulary.”76 For its part, the 1st Infantry Division either was so widely dispersed as to be incapable of serving as a reserve or was dedicated to training the “grossly untrained replacements,” which “rendered the [Division] ineffective as a fighting unit.”77 Within a year of the Constabulary’s activation, only the then-undermanned 1st Infantry Division remained as the sole tactical support if an emergency broke out.78

USFET Commander General McNarney reported to General Eisenhower that forces in Europe were unable to defend the U.S. Zone from outside aggression, nor could they evacuate without British assistance.79 Rating estimates in fall 1946 concluded that the Constabulary held a 65 percent combat efficiency and the 1st Infantry Division maintained only a 20 percent capability.80 In the face of increasing tensions with the Soviet Union, Army commanders were alarmed at the lack of fighting capability in Germany and spent the second half of 1946 preparing to solve the readiness issue.

A 37th Constabulary Squadron tank parade in Limburg, Germany, July 1946

National Archives

The Mission Evolves for the Cold War

By the end of 1946, it was clear that a Nazi resurgence was not going to materialize. The goal of demilitarizing Germany was almost complete. Local governments and police forces worked with their occupiers to secure the zones and maintain law and order. Yet the Soviet threat on the other side of the Iron Curtain was growing. Although the Soviet Army technically demobilized after World War II, it maintained a massive contingent of at least twenty-four divisions in the eastern zone, to the concern of the western Allies.81 One report noted, “the realization served to justify, in the minds of planners, a more equitable distribution of manpower between occupational duties and a combat reserve.”82 This new approach to balance the occupation mission with combat readiness was both a proactive effort to be prepared for a conflict with the Soviets and a reaction to the disintegration of unit effectiveness and continued shrinkage of the forces stationed in Germany. A year into the occupation, the Army of World War II no longer existed. No real combat training occurred after the war ended, and it showed in the inspection assessments of remaining forces. A major initiative, therefore, would have to take place to reorient the occupation units for combat.

After months of planning, USFET began a theater-wide reorganization in February 1947. It had two major components: consolidate units and equipment to increase efficiency and shift the operational focus from occupation management to combat readiness. On 15 March, USFET reorganized as EUCOM; administrative reorganizations took place, which included an array of promotions and transfers among commanders; and a large personnel cut from unnecessary Military Government operations occurred.83 The date marked “the real start toward reconstituting the United States Army in Europe as an effective tactical force.”84 Instead of focusing on OMGUS operations and Constabulary policing, Army planners adapted the mission to combat readiness to prepare for a potential clash with Soviet forces. Of note, this shift began more than a year before the Soviets blocked Western access to Berlin in June 1948, prompting the yearlong Berlin Airlift that flew in millions of tons of supplies to Allied forces and Germans isolated in West Berlin.85 Given the increasing conflicts with the Soviet Union, including President Harry S. Truman’s adoption of a containment strategy in 1947, the Army was preparing for a potential standoff in Germany.86

To begin, EUCOM issued a directive to reduce Constabulary personnel to 18,000 soldiers by 1948, down from its previously authorized 31,000 in 1946, as a first step to shift daily operations away from policing. To do so, Constabulary headquarters eliminated two brigades, five regiments, and eleven of the thirty-two squadrons.87 In tandem with this consolidation, EUCOM planners ordered the Constabulary to reduce unnecessary equipment such as tanks and other armored vehicles.88 Publicly, this shift served a broader narrative that control of policing was being turned over to the Germans. General Harmon told the New York Times that the equipment removal, which accompanied a 20 percent personnel loss, “served to emphasize the nonmilitary aspect of the United States occupation of Germany had assumed.”89 Ultimately, the equipment removal was only a temporary measure.

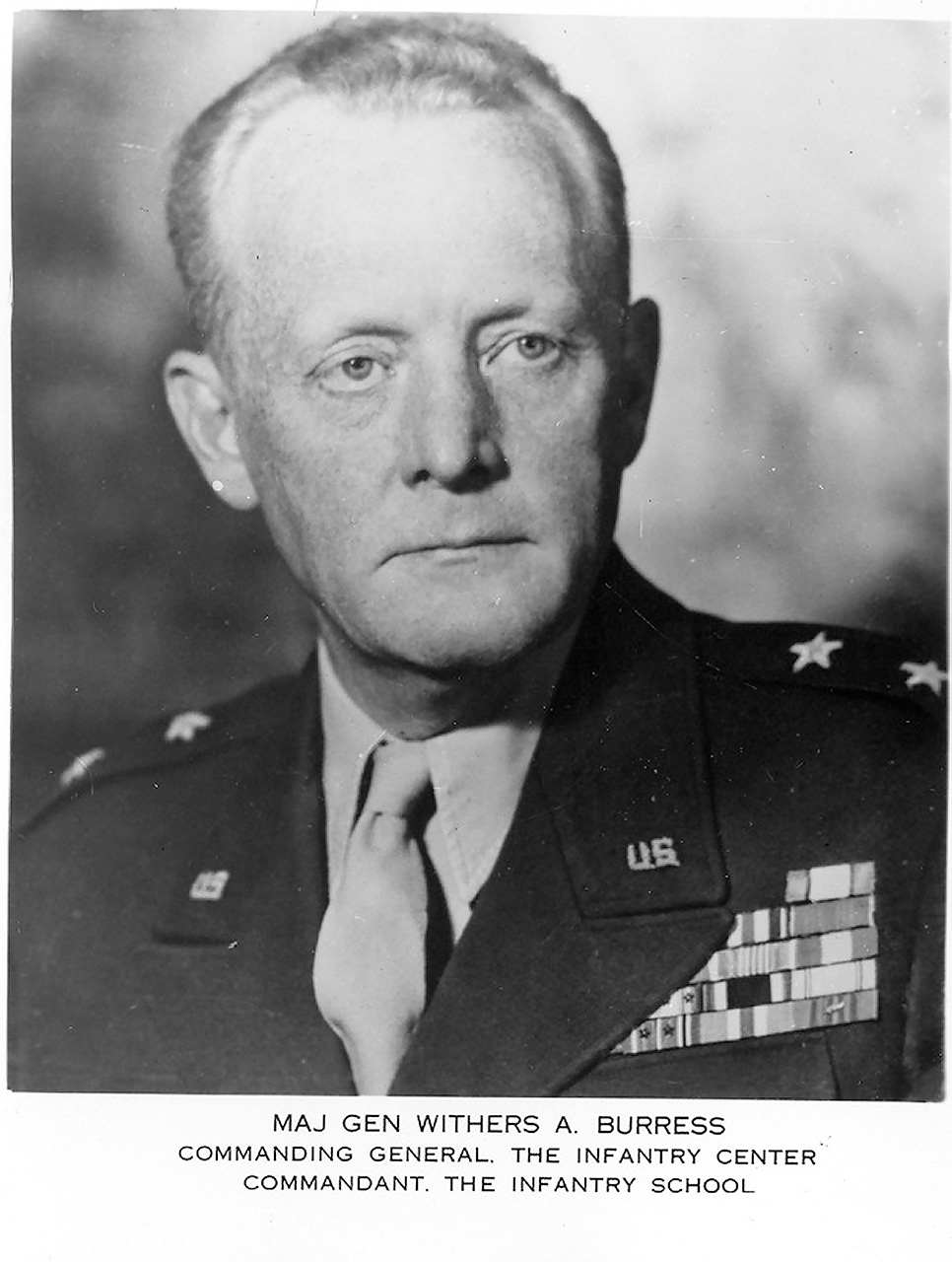

The theater-wide reorganization also brought a change in Constabulary leader ship. On 1 May 1947, Maj. Gen. Withers A. Burress became the new commanding general. At his farewell speech, General Harmon recognized the Constabulary’s mission shift, remarking, “at no time has it been clearer that we ha[ve] an opportunity to contribute so much and so vitally to reconstruction and peace.” He told the crowd he was leaving at a time when the Constabulary had “outgrown its growing pains.”90 Shortly after assuming command, General Burress expanded on General Harmon’s springtime reduction by eliminating patrols in areas that had little to no criminal incidents reported in the previous quarter.91 Throughout the summer, the German police became more independent and, by fall 1947, Constabulary units served primarily in a supervisory capacity. Checkpoint patrols became more important “as a means of affording contact with the general public,” and rural patrols, or those in areas with no criminal incidents, reduced.92

Although the consolidations served to streamline operations, they also exacerbated personnel shortage issues. For example, when Third Army inactivated, Constabulary headquarters offices dramatically expanded their scope of responsibility without additional staff. The police force moved its headquarters from Heidelberg to Bamberg to take over Third Army offices. Before the move, Constabulary offices managed a tactical headquarters for Bavaria. However, the move to the new facility meant that the same staff took on the duties to manage Württemberg-Baden and Greater Hesse, in addition to Bavaria. To compensate, EUCOM leaders requested the remaining Third Army staff of about 1,400 soldiers assist in the transition. However, almost all rotated out within a month, leaving the shrunken Constabulary staff to manage three states with the staff for one.93 Personnel problems such as these were apparent throughout the zone. The quarterly report after the merger explained, “Many positions which were formally considered to be full time jobs in the Military Posts are now being performed [i]n addition to other duties.”94

General Burress

U.S Army

On top of the administrative consolidations, troopers in the field turned over many of their duties to local German police units to focus on the second aspect of the reorganization: combat readiness training. In April 1947, the Lightning Bolt, the unit’s newspaper, explained, “As the German police become more efficient and mobile in assuming responsibility for their own people, and as thousands of DPs leave the zone for Belgium and South America . . . the Constabulary [will be] a static organization, with all units in kasernes [barracks] except for a few border check-points.”95 Rather than being a mobile force out in the field, the troopers consolidated into stationary formations to focus on training. Combined, the consolidations and hand-off “brought troops under better control and made more man hours available for training purposes.”96

As noted earlier, Germany’s lack of sovereignty meant that local police forces had no legal jurisdiction to detain or arrest Allied forces, dependents, or foreign nationals, which necessitated continued U.S. involvement in police and border security functions. In spring 1947, the Constabulary handed most policing authority over to OMGUS offices to free troopers from local patrols. However, as the Constabulary newspaper informed readers that, despite the transfer, troopers “will still be charged with border security control until the ability of the German police is definitely established.”97 In practice, this meant German officers were unattended at border posts and Constabulary troopers arrived when called for support. For example, on the evening of 20 January 1949, German border officers fired on a truck attempting to crash through a U.S.-Czech crossing. The truck hit a tree, and the German officers called for Constabulary support. A patrol from the 53d Constabulary Squadron arrived fifteen minutes later and a firefight ensued. A full platoon arrived hours later. The next day, the Czech driver, who had been attempting to smuggle hidden individuals into the U.S. Zone, surrendered and Constabulary troopers arrested him and turned away those hiding in the truck.98

Alongside the 1st Infantry Division, Constabulary troopers began combat training at the former German training facility near Grafenwöhr. The Grafenwöhr camp, which the Army still uses today, opened in May 1947 and marked the beginning of EUCOM’s public commitment to establish a combat reserve in Germany, as it shifted the occupation’s focus from local security to tactical proficiency. Before 1947, training took place on the lower unit level and focused on border security, lightning raids, and individual readiness to compensate for poor soldier quality in the replacement system. After 1947, training focused on theater-level combat readiness. This shift meant that “Constabulary training began to shift away from the individual and toward the platoon . . . to serve as theater assets.”99 In place of Constabulary School classes to learn interpersonal skills and policing strategy, troopers joined elements of the 1st Infantry Division in combat exercises and field maneuvers in areas across the zone.

As Constabulary training shifted from police duties to combat readiness, leaders predicted the “Constabulary unit would be deactivated [i.e., inactivated] over the next three years as the German government assumed responsibility for internal security.”100 If the transition was completed as planned, the Constabulary would no longer be directly responsible for policing. Many considered this slow elimination of the police force as a reflection of the unit working itself out of a job. If fully successful, German police would be capable of handling all internal security. The visible marker of that success was the movement of troopers from local patrols to Grafenwöhr.

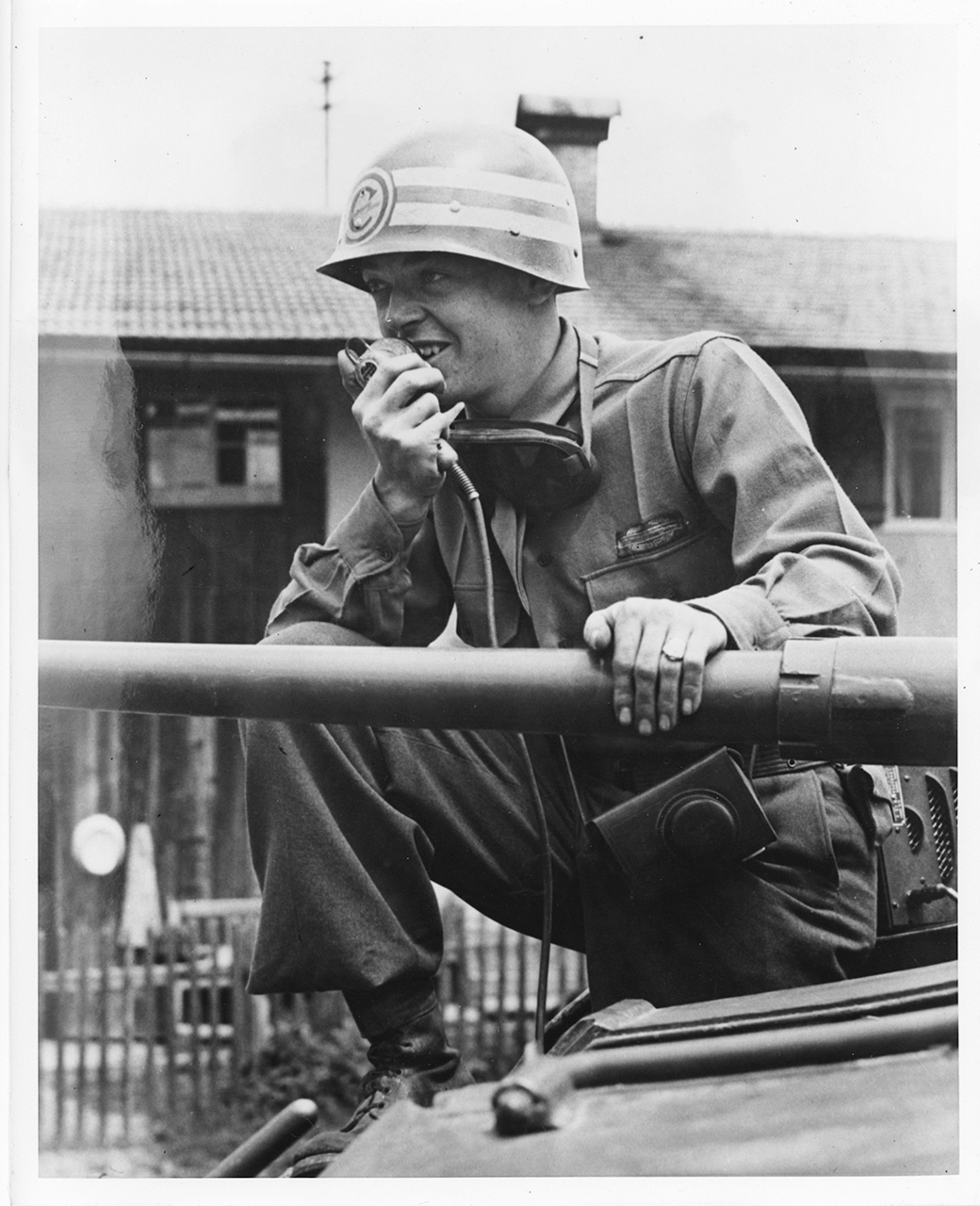

Cpl. Robert Ryan conducts radio operator training at Sonthofen, Germany.

National Archives

On 15 November 1947, another key reorganization took place that cemented the occupation’s transformation to combat readiness and defense. USFET successor U.S. Ground and Service Forces, Europe, organized in February 1947 alongside the formation of EUCOM, became U.S. Army, Europe (USAREUR). General Clay and General Huebner continued to lead the forces in Germany, but the new designation indicated a further shift to combat training. As a later report summarized, EUCOM was “established to control a potentially powerful enemy nation.” As such, occupation forces “came to be viewed more and more . . . as a bulwark against communism.”101

A week after the redesignation, General Clay sent a request to the Department of the Army to organize some elements of the Constabulary into field artillery battalions. Eight months after the Constabulary lost its armored equipment to save resources, General Clay argued that artillery units would be vital in case of an emergency. He later explained:

I changed them to heavily armored regiments with support artillery and infantry when I took over because it was obvious to me that we weren’t going to fight the Germans. If we were going to do any fighting over there it was going to be a major enemy, and we weren’t going to do it with lightly armed troops.102

The Army approved the request in December. However, because the Constabulary’s Table of Organization had no authorization for this type of equipment, the envisioned combat battalion would have to be organized outside the unit. General Huebner accomplished this by eliminating more squadrons and troops from the Constabulary.103 This year-end reduction and formation of an artillery battalion in occupied Germany set the stage for another major reorganization months later.

In 1948, the Constabulary further stream lined and reorganized to reflect EUCOM’s tactical emphasis. Shortly before the Berlin Airlift began in June, the Department of the Army unofficially authorized EUCOM’s request to reorganize the 1st Infantry Division and the Constabulary into armored cavalry forces. Maj. Gen. Isaac D. White, the Constabulary’s fourth commander in two years, met with Generals Clay and Huebner to discuss the reorganization. The three agreed to change the Constabulary’s organizational structure into an armored division.104 However, yet again, the ongoing police mission prevented it becoming a division, which would have helped with broader, theater-wide training goals. To compensate, the generals agreed to reorganize the Constabulary into a modified corps with three armored cavalry regiments.105

A series of transformations dramatically altered the nature of the once-mobile police force. First, the Army approved the generals’ proposal to reorganize three Constabulary regiments into armored cavalry regiments. Then, EUCOM received approval to reduce the Constabulary’s operational commitments. To do so, OMGUS took over even more responsibility to put down local disturbances and manage some police functions.106 General White pulled the troopers from some Czech and Soviet zonal crossings. In summer 1948, Stars and Stripes noted that tight military control of the crossing points is “no longer necessary due to the high discipline of the military forces and effective cooperation with German police.”107 Constabulary units also increased training at Grafenwöhr.

Throughout the year, the Grafenwöhr training camp underwent a series of building projects to expand its capabilities. To accommodate more soldiers, Army engineers and local contractors constructed housing across eight new camps.108 Units from the Constabulary and the 1st Infantry Division rotated through the camp, conducting a variety of training and maneuvers. The police force also took over a combat training site at Vilseck to develop the armored cavalry regiments.109 During the first half of the year, the Constabulary’s ongoing security mission meant it could not be consolidated or completely pulled from daily operations as the 1st Infantry Division had. Therefore, smaller police units rotated in and out of Vilseck for eight-week programs.110

On 23 June 1948, the day before the Soviets blockaded Berlin, EUCOM instructed Constabulary commanders to completely stop training for the police mission and to instead focus exclusively on the tactical mission.111 Days later, the Berlin Airlift (Operation Vittles) began and units at Grafenwöhr, including the 2d Constabulary Regiment and the newly formed 91st and 94th Field Artillery Battalions, switched from small-unit to full division training.112 The decision to end police training meant that the U.S. Army in Germany unofficially stopped focusing on the occupation mission; all efforts strove to achieve full combat readiness in case the Cold War turned hot.113 The Constabulary, initially created to compensate for manpower shortages, would no longer be a mobile police force, but the unit retained its headquarters and insignia. The Military Review reflected, “During the first year and a half of its existence, the Constabulary was primarily a police force. Now the emphasis was shifting to a purely military mission which required changes in training, planning, and organization.”114 As such, General Huebner balanced Constabulary strength levels, both in personnel and equipment, with the 1st Infantry Division to bring the combined units to normal division strength.115

General White inspects troops of the Constabulary’s 70th Field Artillery Battalion, Giessen, Germany, July 1949.

National Archives

Just one month after police training ended, division-level exercises got underway. The 1948 maneuvers, including exercises Black, Green, Prime, and Normal, employed the entire 1st Infantry Division and at least one Constabulary regiment.116 The field exercises aimed “to test mobility, communications, and logistics support, to develop liaison with French and British elements . . . and to develop tactical procedures.”117 After these initial maneuvers, training in occupied Germany continued to expand. For 1949, EUCOM planners sought to fully integrate all U.S. military services and units in Germany into the training program. The season-ending maneuver, Exercise Harvest, deployed around 112,000 troops (almost every soldier in EUCOM), covered the whole of the U.S. Zone, and incorporated the Army, Air Force, and Navy in a full-scale joint maneuver. The annual report that year noted that the exercise “demonstrated for the first time the striking force and defense capabilities of U.S. forces in Germany.”118

The disorderly and ineffective units of the early occupation were gone. In their place was a burgeoning army for the Cold War. Following Exercise Normal, General Huebner told soldiers at Grafenwöhr, “You are today, in my opinion, the best trained . . . in the United States Army. You don’t need to take a back seat. You have the ‘know how.’ You can now step upfront and lead the way for others.”119 The poorly trained, badly behaved GIs that had arrived in Germany at the end of the war had given way to a contingent prepared for a possible conflict. The training program successfully transformed the occupation forces from inefficient, disorganized teams into a cohesive defense force preparing to defend the zone and train incoming replacements. To be sure, the forces in Germany in the late 1940s did not have a combat readiness comparable to their World War II predecessors. However, the initiative to develop a force that could respond to a Soviet invasion was underway.

The Cold War Mission and Constabulary Inactivation

From spring 1949 to summer 1950, a series of events codified the Army’s mission transformation in Germany from policing to defense, all of which contributed to the eventual inactivation of the Constabulary. First, in April 1949, while the Berlin Airlift was ongoing, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) formed. The international coalition’s basic charter stated that an attack on one member was an attack on all members. Even though West Germany did not become a NATO member until 5 May 1955, the original charter included a member nation’s occupied territory as part of the defense clause. As such, America’s membership in NATO committed the Army to stand and defend West Germany.120 Second, in May 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) formed, and the State Department announced that its newly formed High Commission for Occupied Germany (HICOG) would take over management of the military government.121 The transfer was a sigh of relief for Army leaders, as they had been asking for it since fall 1945. The formation of HICOG dissolved OMGUS and freed the Army to formalize the mission change from occupation to defense. It is important to note that although the Army’s management of the occupation ended, its legal structure did not. The continued military occupation, codified in a new Occupation Statute (passed May 1949), secured the legal framework that allowed the Army to station troops inside West Germany—without requiring preapproval from the Bonn government to conduct training maneuvers or a troop buildup.122 The new statute also confirmed that Germans still could not detain or arrest non-German personnel, thus necessitating the Army’s continued involvement in border operations.

Third, in August 1949, the Soviets successfully tested a nuclear bomb. Historians Marc Trachtenberg and Ingo Trauschweizer rightly point out that military leaders in the late 1940s relied on America’s nuclear monopoly to justify keeping personnel levels low in Europe, instead relying on a trip wire strategy that would deploy atomic weapons if attacked.123 Once the Soviets possessed their own atomic bomb, the trip wire strategy became irrelevant and the low number of personnel in Germany became a liability instead of an asset. Fourth, in December 1949, China converted to communism. On its own, this event was more of a political issue for officials in Washington than it was for commanders in Germany. However, coupled with the Soviets attaining the bomb, commanders in Germany worried about the growing power of communism and its potential impact for Western Europe.

Finally, in June 1950, forces in North Korea invaded their southern neighbor and “everything changed practically overnight.”124 When the Korean War began, EUCOM personnel, including all tactical and service units, numbered a mere 80,000 soldiers compared to the estimated 360,000 Soviet ground troops in six armies on the other side of the East German border.125 As professor Gregory F. Treverton explained, “It did not take paranoids, or conspirators, to see the [Korean] invasion as, at worst, a feint in preparation for an attack in Europe, at best as an indication that weakness invited adventure.”126

Given the international landscape and conflicts with the Soviet Union, Army planners understood the necessity of a strong defense in Western Europe. General Matthew B. Ridgway later remarked, “It’s just a utopian dream to think that [an invasion] could not happen because you are dealing with a ruthless, coldly calculated government in the case of the Soviet Union, and if at any time they judged it to be in their interest to do so, they wouldn’t hesitate . . . regardless of the cost to themselves.”127 Army commanders in Germany also paid close attention to public opinion and appreciated that America’s military presence provided a sense of security. A 1950 report noted, “To most Germans, the news that the Americans had gone into action in Korea was a morale booster. Previously, the Germans believed that the U.S. would quit Germany when the Soviets advanced.”128 The Army’s response to all these events and sentiments was a massive troop buildup to secure the peace in Western Europe.

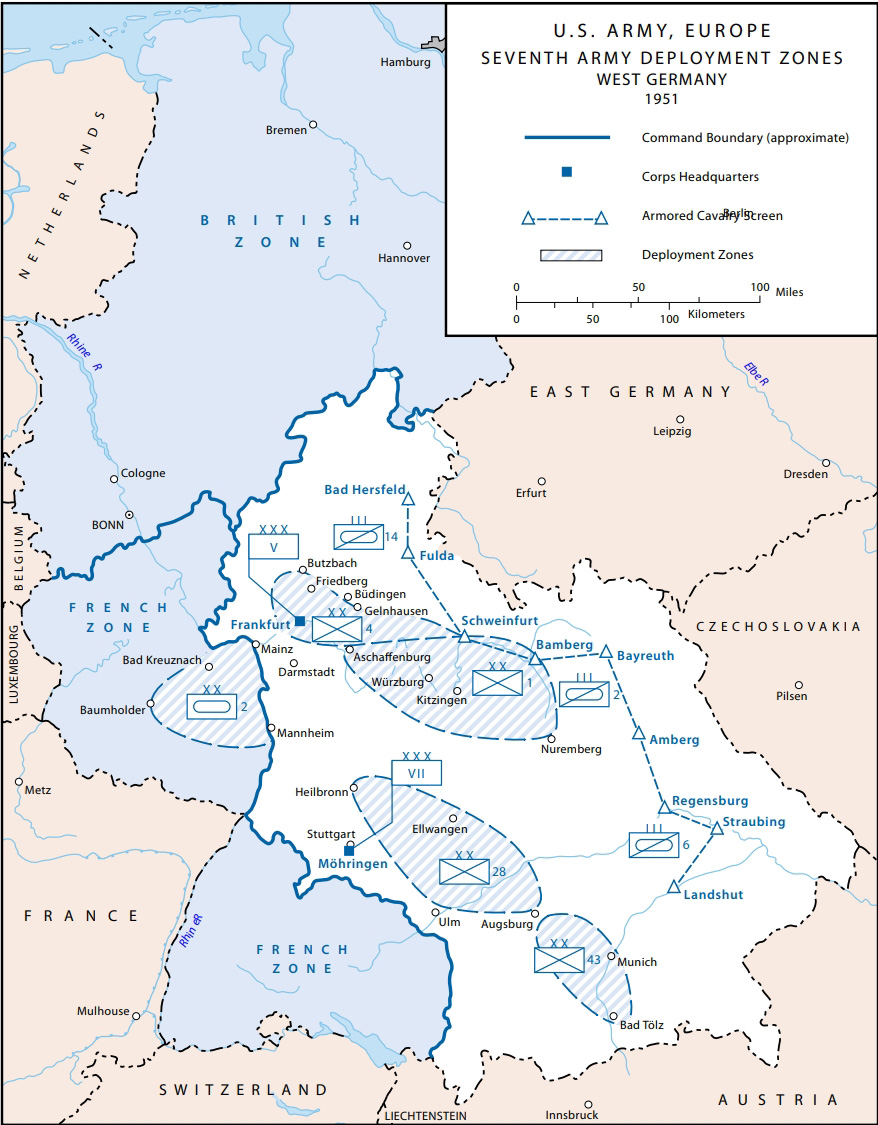

To provide EUCOM with much-needed tactical support, Seventh Army activated in November 1950. Simultaneously, EUCOM planners inactivated the U.S. Zone Constabulary headquarters. By the time the police force inactivated, “The unit had provided a wide range of police services to a continent in need of stability and order. The men who served in the unit eventually managed to win the hearts and minds of the civil population and set the stage for German admission into the NATO framework.”129 From 1946 to 1950, the Constabulary had fully trans formed itself from a mobile police unit that took over for a shrinking, inefficient World War II force to a unit focused on combat training for the Cold War. The Lightning Bolt noted in July 1950 that “the primary mission, that of security, has never changed. The Constabulary today, a compact, fast-moving arm, built principally around armor. . . stands ready, day or night, to move into any part of the zone.”130 General White added, “To the Germans, the trooper is a symbol of help and progress, a signpost on the road to democracy. To the American in Germany, the trooper is an assurance that the job now being done will not have to be done again.”131 In four years, the Constabulary successfully contributed to the security and stabilization of the zone and did so while transforming from a mobile police unit to a static combat force.

By the time Lt. Gen. Manton S. Eddy took command of Seventh Army, the soldiers in Germany had spent almost three years conducting field maneuvers or attending training courses in one of the newly opened technical schools. Although it is true that forces in Germany in 1950 did not serve as a true deterrent to the Soviets, adding four divisions in 1951 did not provide that either. Instead, the buildup “was largely a political signal, as even five American divisions had little hope of containing a determined Soviet offensive.”132 One report even argued, “the soldier serving in the European Command in 1950 was probably one of the best-trained in the U.S. Army.”133 From the original reorganization in February 1947, Army leaders in Germany spent four years working toward that goal before Seventh Army activated.Stars and Stripes confirmed this by noting, “The transformation of U.S. Armed Forces in Europe from occupation to tactical security units can be traced from September 1948 when the first large-scale troop maneuvers. . . were held at Grafenwöhr.”134 Personnel from the Constabulary and the 1st Infantry Division formed the bedrock of the developing Cold War Army, creating both the physical and administrative structures of a training framework that Seventh Army would employ for years to come.

After three years of combat training, the two units transferred into Seventh Army upon its reactivation and established a security shield for their arrival in May 1951. At the beginning of the year, the 1st Infantry Division scattered across the northern portion of the zone to provide a screen for the incoming 4th Infantry Division. Upon arrival, the 4th Infantry Division traveled south from Bremerhaven and moved into areas north and northeast of Frankfurt where the Rhine and Main rivers met. Doing so offered protection for the incoming 2d Armored Division, which moved into areas west of the Rhine. The Constabulary deployed in the same staggered pattern in the southern portion, providing protection for the recently activated National Guard 28th and 43d Infantry Divisions.135

These shields were strategically important. During the period of Seventh Army’s arrival, Army leaders continued to suspect that the outbreak of the Korean War was a Soviet ruse for an invasion into West Germany. The arriving divisions came ashore with little equipment and virtually no capability to defend themselves as separate units and therefore relied on the existing proficiency of 1st Infantry Division and Constabulary forces to protect them. By fall 1951, Seventh Army’s five divisions, divided between V and VII Corps, had spread out to cover the southern half of West Germany.

General Eddy inspects troops of the 2d Constabulary Brigade in Augsburg, Germany, September 1950.

National Archives

Upon their arrival, EUCOM leaders discovered that the new divisions did not have the same level of combat proficiency as their existing counterparts in Germany. Early assessments showed that the 4th Infantry Division was only 45 percent combat ready when it shipped to Europe and the 2d Armored Division carried a 65 percent readiness rating.136 This problem persisted for the National Guard’s 28th and 43d Infantry Divisions, as they had received even less training than their Regular Army counterparts. EUCOM commanders acknowledged the deficiency, which “had to be weighed against their progressively increasing capabilities . . . and against the possibility of hostility in Europe.” Because the units could be trained while in Germany, “it was considered reasonable to move them in.”137 To fulfill manpower quotas as quickly as possible, EUCOM accepted the units with their lower states of readiness. Leaders thought they could bring the new soldiers up to desired levels through a combination of field maneuvers and attendance at the training centers and technical schools already in place throughout southern West Germany.

The new soldiers also relied on the existing forces for their practical experience and skills. Because the Army still had to maintain authority over border control issues, Constabulary troopers were able to advise new soldiers on those procedures. This process was made slightly easier because the 15th and 24th Constabulary Squadrons continued to provide security and law enforcement into two outposts until December 1952, a rare example of subordinate units remaining active after their headquarters was eliminated.138 Troopers also provided practical advice to incoming soldiers on issues from German language skills and cultural norms to procedures about maneuver damage claims and training schedules. Their incorporation into Seventh Army was an incredible asset for the new divisions, especially because most young soldiers were recent draftees and did not have previous experience in Germany during the war.

Seventh Army soldiers soon joined the already-developed training schedule at the various camps and technical centers throughout southern West Germany. Their first real test, Exercise Combine, took place in October 1951 in front of an international audience of military leaders, journalists, and foreign dignitaries. The maneuver was typical of what the Army had been doing in Germany for three years: a massive contingent of soldiers traveled across a huge swath of land to conduct a multistage exercise to test combat proficiency, communications, and support services. Exercise Combine involved more than 100,000 soldiers, spanned 150 square miles through myriad towns and villages, and took place over a ten-day period.139 According to General Thomas T. Handy, the maneuver had the dual benefit of providing vital tactical training and “show[ing] any potential aggressor that we stand as a united and integrated force in the defense of Western Europe.”140 Maneuvers such as these became the hallmark of the Cold War Army throughout the rest of the 1950s. Combat proficiency was the benchmark of assessing mission success because Seventh Army’s primary objective was to serve as a Cold War deterrent.

The soldiers that carried out these maneuvers became the face of the Army’s Cold War mission, for domestic and foreign audiences alike. In 1955, the Army television show The Big Picture summarized, “Never before in American history has a peacetime army been so strenuously trained.”141 Historian Donald A. Carter once argued that just as the doughboy and GI Joe represented the soldier of earlier wars, “the men guarding the inter-German border dominated the public image of the modern American soldier.”141 Indeed, during the 1950s, the Army’s “One Army On Alert” campaign promoted these soldiers as the “ultra-modern, relevant Army.”143

In November 1950, Constabulary troopers of the 2d, 6th, and 14th Armored Cavalry Regiments transferred into USAREUR and exchanged the Circle “C” patch for Seventh Army’s “Seven Steps to Hell” insignia.144 Yet, the Constabulary logo continued until December 1952 with the remaining 15th and 24th Squadrons. In the announcement of the squadron’s inactivation, Stars and Stripes remarked, “The year 1953 will be born without a single Constabulary patch in Germany or anywhere else except the memory of the thousands of men who held the standards of America aloft in a troubled Europe.”145

Members of the 16th Constabulary Squadron show a mortar to local German children near Berlin, March 1949.

National Archives

Author’s Note

I would like to thank the members of the Second World War Research Group North America, Thomas Boghardt, Donald Carter, Jon Hoffman, and Adam Seipp for providing invaluable feedback during the development of this project.

Notes

1.“Operation “ECLIPSE”: Appreciation and Outline Plan,” Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces, 10 Nov 1944, 1.

2. Interv, Richard D. McKinzie with Lucius Clay, 16 Jul 1974, transcript, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, MO, 29–30.

3. “Army Plans Bold Experiment,” Stars and Stripes, 11 May 1946, Mediterranean Rome Edition. Unless otherwise noted, all references to Stars and Stripes refer to the European Edition.

4. “U.S. Constabulary Celebrates 5th Anniversary Tomorrow,” Stars and Stripes, 30 Jun 1951.

5. From November 1950 to December 1952, only two squadrons remained active. “All but 2 Constab Units Absorbed by 7th Army,” Stars and Stripes, 13 Apr 1952.

6. Scott Allen, The U.S. Zone Constabulary, 1946–1952: Organizational Change in Occupied Germany (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Army Command and General Staff College, 2013); Kendall D. Gott, Mobility, Vigilance, and Justice: The U.S. Army Constabulary in Germany, Global War on Terrorism Paper 11 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2005); David A. Kaufman, “Mobility, Vigilance, Justice: The U.S. Constabulary Forces in Germany, 1946–1952,” Army Historical Foundation, https://armyhistory.org/mobility-vigilance-justice-the-u-s-constabulary-forces-in-germany-1946-1952/; Michael A. Rauer, “Order Out of Chaos: The United States Constabulary in Postwar Germany,” Army History 45 (Summer 1998): 22–35.

7. Drew Middleton, “The Seventh Army,” Combat Forces Journal 3 (Aug 1952): 14.

8. Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 2008); Susan Carruthers, The Good Occupation: American Soldiers and the Hazards of Peace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). 9. Oliver Frederiksen, The American Military Occupation of Germany, 1945–1953 (Darmstadt, Germany: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe, 1953), 62.

9.Oliver Frederiksen, The American Military Occupation of Germany, 1945–1953 (Darmstadt, Germany: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe, 1953), 62.

10. David Colley, “‘Circle C Cowboys’: Cold War Constabulary,” VFW (Jun/Jul 1996), 23.

11. Harold E. Potter, Redeployment, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1945– 1946 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1947), 88–89.

12. Bell Wiley, The Role of Army Ground Forces in Redeployment (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, 1946); John C. Sparrow, History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army, Department of the Army Pamphlet 20–210 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1952).

13. “Points ’N Counterpoints,” Stars and Stripes, 27 May 1945, Mediterranean Rome Edition.

14. James M. Snyder, The Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 3 October 1945–30 June 1947 (Heidelberg, Germany: Headquarters, U.S. Constabulary, 1947), 1.

15. Earl Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944–1946, Army Historical Series (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1975), 320. 16. Harold E. Potter, The First Year of the Occupation, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1945–1946 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1947), 78.

16. Harold E. Potter, The First Year of the Occupation, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1945–1946 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1947), 78.

17. AAR, Report of Operations (Final After-Action Report), 12th Army Group, vol. I (U.S. Forces European Theater: Headquarters, 12th Army Group, Jul 1945), 31; Harold E. Potter, The United States Constabulary, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1945–1946 (Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1948), 3.

18. Benjamin A. Harris, United States Zone Constabulary: An Analysis of Manning Issues and Their Impact on Operations (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Command and General Staff College, 2006), 19.

19. Ziemke, U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 339–40.

20. Interv, Jean Smith with Lucius Clay, 25 Feb 1971, transcript, Columbia University Oral History Project, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, KS, 651.

21. Potter, United States Constabulary, 21. For the Constabulary’s support of the intelligence corps, see Thomas Boghardt, Covert Legions: U.S. Army Intelligence in Germany, 1944–1949, U.S. Army in the Cold War (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2022).

22. Quoted in Potter, United States Constabulary, 25.

23. Francis S. Chase, Reorganization of Tactical Forces, VE-Day to 1 January 1949, Occupation Forces in Europe Series (Karlsruhe, Germany: Historical Division, European Command, 1950), 29. For more on the organization and equipment, see “The U.S. Constabulary in Postwar Germany, 1946–1952,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, Apr 2000, https://history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/constab-ip.html.

24. Potter, First Year of the Occupation, 258–63.

25. John C. Sparrow, History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1952), 252.

26. Allen, U.S. Zone Constabulary, 1946–1952, 23; Gott,Mobility, Vigilance, and Justice, 10.

27. American Military Government of Occupied Germany, 1918–1920: Report of the Officer in Charge of Civil Affairs, Third Army and American Forces in Germany (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943), 25. The Louisiana Maneuvers were a key development in the U.S. Army’s preparation for World War II. For a general overview, see “The Louisiana Maneuvers,” The National War II Museum, 11 Jul 2017, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/louisiana-maneuvers.

28. Charles B. MacDonald, The Last Offensive, United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1993), 379–81; and “U.S. Army Central Timeline,” U.S. Army Central, accessed 27 Jun 2024, https://www.usarcent.army.mil/About/History/Timeline/.

29. William Tevington, The United States Constabulary: A History (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, 1998), 5.

30. “World’s Top Police Force Is Goal of Constabulary,” Stars and Stripes, 30 Jun 1946.

31. E. N. Harmon, Milton McKaye, and William Ross McKaye, Combat Commander: Autobiography of a Soldier (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970), 282.

32. “Constabulary Marks 2d Anniversary,” Lightning Bolt, 1 Jul 1948, Box 15, Paul L. Webb Papers, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC), Carlisle Barracks, PA.

33.Mary Lee Stubbs and Stanley Russell Connor, Armor-Cavalry, Part I: Regular Army and Army Reserve, Army Lineage Series (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1969), 25, 35.

34. “Mechanized Constabulary Scheduled for Occupation: USFET Plans Security Force on Trial Basis,” Stars and Stripes, 14 Nov 1945, German Edition; “Army May Organize European ‘Mounties,’” Stars and Stripes, 19 Nov 1945, Mediterranean Rome Edition.

35. History of the U.S. Constabulary, 10 Jan 46–31 Dec 46 (Headquarters, European Command: Historical Division, 1947), Box 8-3.1 CA 37, Library and Archives, U.S. Army Center of Military History, Fort McNair, DC, 9–10.

36. “Trooper’s Handbook,” 1st ed., United States Zone Constabulary (Headquarters, U.S. Zone Constabulary, 13 Feb 1946), 11.

37. “US Constabulary Prepares for Occupation Duty,” Military Government Weekly Information Bulletin, 36 (8 Apr 1946): 11.

38. Tevington, United States Constabulary, 15.

39. Frederiksen, American Military Occupation of Germany, 66.

40.History of the U.S. Constabulary, 10 Jan 46–31 Dec 46, 7.

41. “Trooper’s Handbook,” 1.

42. Harold E. Potter, The Second Year of the Occupation, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1946–1947 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1948), 4.

43. History of the U.S. Constabulary, 10 Jan 46–31 Dec 46, 11. See also Snyder, Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 113.

44. Snyder, Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 130.

45. History of the U.S. Constabulary, 10 Jan 46–31 Dec 46, 17.

46. Ibid., 14.

47. Memo, HQ, U.S. Constabulary for European Cmd, 11 Jan 1948, Box 603, Ofc of the Ch of Staff, Incoming Msgs, 1946–1951, Record Group (RG) 549, Records of United States Army, Europe, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD (NACP).

48.Gott, Mobility, Vigilance, and Justice, 24–25.

49. “Quarterly Report of Operations: April– June 1947,” HQ, U.S. Constabulary, Box 2147, Unit Histories, 1940–1967, U.S. Constabulary Sec., RG 338, Records of U.S. Army Operational, Tactical, and Support Organizations (World War II and Thereafter), NACP.

50. Memo, HQ, U.S. Constabulary for European Cmd, 11 Jan 1948.

51. Harris, United States Zone Constabulary, 37.

52. “German Police Relieve Constab of Train Duty,” Lightning Bolt, 11 Jun 1948, USAHEC, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

53. Robert L. Gunnarsson Sr., American Military Police, 1945–1991: Unit Histories (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 15.

54. “Statistical Report of Operations, 1 July to 31 December 1946,” in United States Constabulary (Heidelberg, Germany: 1947), Box 2148, Unit Histories, 1940–1967, U.S. Constabulary Section, RG 339, NACP.

55. Snyder, Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 152–53. See also George F. Hofmann, Through Mobility We Conquer: The Mechanization of U.S. Cavalry (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 433.

56. For more on the camp, see “Eschwege Displaced Persons Camp,” Holoc au st Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed 27 Jun 2024, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/eschwege-displaced-persons-camp.

57. Memo, U. P. Jonckheere for A. C. Dunn, 6 Mar 1948, sub: Raid on Eschwege Camp, folder 5, box 1, Withers Burress Papers, Virginia Military Institute Archive, Lexington, VA.

58. Harmon, McKaye, and McKaye, Combat Commander, 283.

59. Ibid., 286.

60. Ibid., 285.

61. “Quarterly Report of Operations, October–December 1947,” Headquarters Troop, U.S. Constabulary, 4, box 34, Adjutant General’s Office Records, U.S. Army, RG 407, Adjutant General’s Office, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, MO.

62. Ibid., 5.

63. “Sgt. Luddy Active in GYA Work,” Lightning Bolt, 21 Feb 1947, USAHEC, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

64. Snyder, Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 209.

65. Gott, Mobility, Vigilance, and Justice, 29.

66. See Harold Potter, Third Year of the Occupation, The Third Quarter: 1 January–31 March 1948, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1947–1948 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1948), 108; and Joachim Nagel, “The Economic and Currency Reform of 1948: The Basis for Stable Money,” Deutsche Bundesbank: Eurosystem, 28 Aug 2023, https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/contributions/the-economic-and-currency-reform-of-1948-the-basis-for-stable-money-915302.

67. William E. Stacy, U.S. Army Border Operations in Germany, 1945–1983 (Heidelberg, Germany: Military History Office, Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe and Seventh Army, 1984), 61.

68. Harris, United States Zone Constabulary, 87.

69. Snyder, Establishment and Operations of the U.S. Constabulary, 138–40.

70. Potter, Second Year of the Occupation, 6. See also Harold E. Potter, The Third Year of the Occupation: The Fourth Quarter: 1 April–30 June 1948, Occupation Forces in Europe Series, 1947–1948 (Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the Chief Historian, European Command, 1948), 61–62.

71. This figure includes the small Women’s Army Corps (WAC) Constabulary detachment, which maintained less than one hundred enlisted troops. Quarterly Historical and Operational Report, 1 April 1948–30 June 1948 (Headquarters, WAC Detachment: U.S. Constabulary), Box 2148, Unit Histories, 1940–1967, U.S. Constabulary Section, RG 338, NACP.

72. 1 ID Station List, 20 Oct 1948, 1–4, in James Scott Wheeler, The Big Red One: America’s Legendary 1st Infantry Division (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 373.