Army Civilian Development

By T. Gregg Thompson & Frank Wenzel

Article published on: July 1st, 2025 in the Army Civilian Professional Journal Issue 1

Read Time: < 10 mins

Army civilian professionals from U.S. Army installations in Germany and Italy attending the Civilian Education System Intermediate Course Phase II on Clay Kaserne in Wiesbaden, Germany, 26 July 2024. The course provides Army civilian leaders educational opportunities throughout their career. (Photo by Mary Del Rosario; photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Army civilians continually develop their leadership abilities through a career-long synthesis of their training, education, and experiences. This professional development addresses short-term and career individual needs, organization missions, and long-term Army requirements. Developing leaders to their fullest potential requires continual investment by the individual, supervisors, peers, and the institution. All leaders must contribute to leader development daily to ensure the Army can meet current and future needs. Investing in the development of Army civilians strengthens our profession, enables mission accomplishment, and prepares our Army for the future. This article makes the case that investments in leader development should be a priority for all supervisors of civilians.

An educated workforce pays dividends for years to come by ensuring the Army can adapt to future uncertainties. Investing in our current and aspiring Army civilian supervisors improves organizations and sends a clear message to those supervisors and other employees that you’re investing in their development. The Army Management Staff College (AMSC) is a unique asset that delivers this education to civilians through the Civilian Education System (CES).

The Army centrally funds the cost of Army civilians’ attendance at required CES courses. CES graduates and their supervisors overwhelmingly report that their organization improved due to employee CES completion, they recommend the course to peers, and they often comment that they’re going to recommend the course to their boss to further improve their organization.1

The Army’s Civilian Education System is the foundation of civilian professional development and provides educational course opportunities that civilian supervisors can utilize throughout their careers.

Employees who feel that the Army is investing and interested in them demonstrate greater initiative, contribute at a higher level, and take a more active role in their own subordinates’ development. Additionally, 94 percent of workers report that they would stay with their organization longer if they had access to employee education.2

The Role of Army Civilians

Although civilians have been part of the Army since 1775, a dramatic change in the cohort occurred in the first decade of this century. Operational demands coupled with a recognition that civilians are members of the Army profession altered perceptions and functions of Army civilians.3 Until then, 96 percent of the Civilian Corps were in lower GS grades, members of the Army Civilian Corps weren’t considered members of the Army profession, and civilians were primarily technical experts locally hired to fulfill local specified tasks.4 This changed dramatically as the Global War on Terrorism and fiscal considerations weighed on the Army total force, requiring more civilians in leader and higher-grade positions. The need for a civilian leader development mechanism within the Army became apparent as the civilian cohort evolved into a white-collar, leader, and managerial workforce.5 Civilians now comprise 23 percent of the Army’s workforce and provide stability and continuity in war and peace, and are integral to our war plans, enabling the Army to meet responsibilities outlined in Title 10 USC and the Army Vision and Strategy.6 This led to numerous codifications requiring workforce training, education, and supervisory development of capable, high-performing leaders to operate in complex environments.7 This is essential since the Army can’t function without its civilian employees.8

Why Is a Dedicated CES Experience Important?

The Army’s Civilian Education System is the foundation of civilian professional development and provides educational course opportunities that civilian supervisors can utilize throughout their careers. Centrally funded for almost all Army civilians, CES courses are required for all Army civilian supervisors.9

Formal college education is a mainstay of an individual’s development. However, like the civilian sector, the Army continues to invest in employees after their formal college education is complete and most executives in the private sector believe employee education is a critical part of their business strategy.10 Employee education boosts individual and organizational performance, allowing employees to become more effective while also increasing job satisfaction, reducing employee turnover, and positively impacting organization culture. A study of one U.S.-based company found that employee turnover dropped by over 30 percent by introducing training and education.11

Only 37 percent of the Army’s 32,000 civilian supervisors have completed their required CES courses.12 This is concerning since poorly educated employees are disengaged, take more sick days, undermine the work of colleagues, miss deadlines, and produce fewer referrals to potential new employees.13 An educated workforce increases retention rates. Ninety-four percent of employees stay at their job longer when employers invest in their career development.14

As the executive agent for the Army’s Civilian Education System, AMSC operates as part of Army University educating and developing Army civilians for leadership and management responsibilities throughout the Army providing the premier leader development experience, igniting the leadership potential of every Army civilian to operate in complex environments now and in the future.15 This creates a cohort of Army civilians who are knowledgeable leaders, collaborators, and innovators. The Army invests heavily in developing the leadership skills of its civilians to provide more professional, capable, and agile leaders for times of change and uncertainty.16

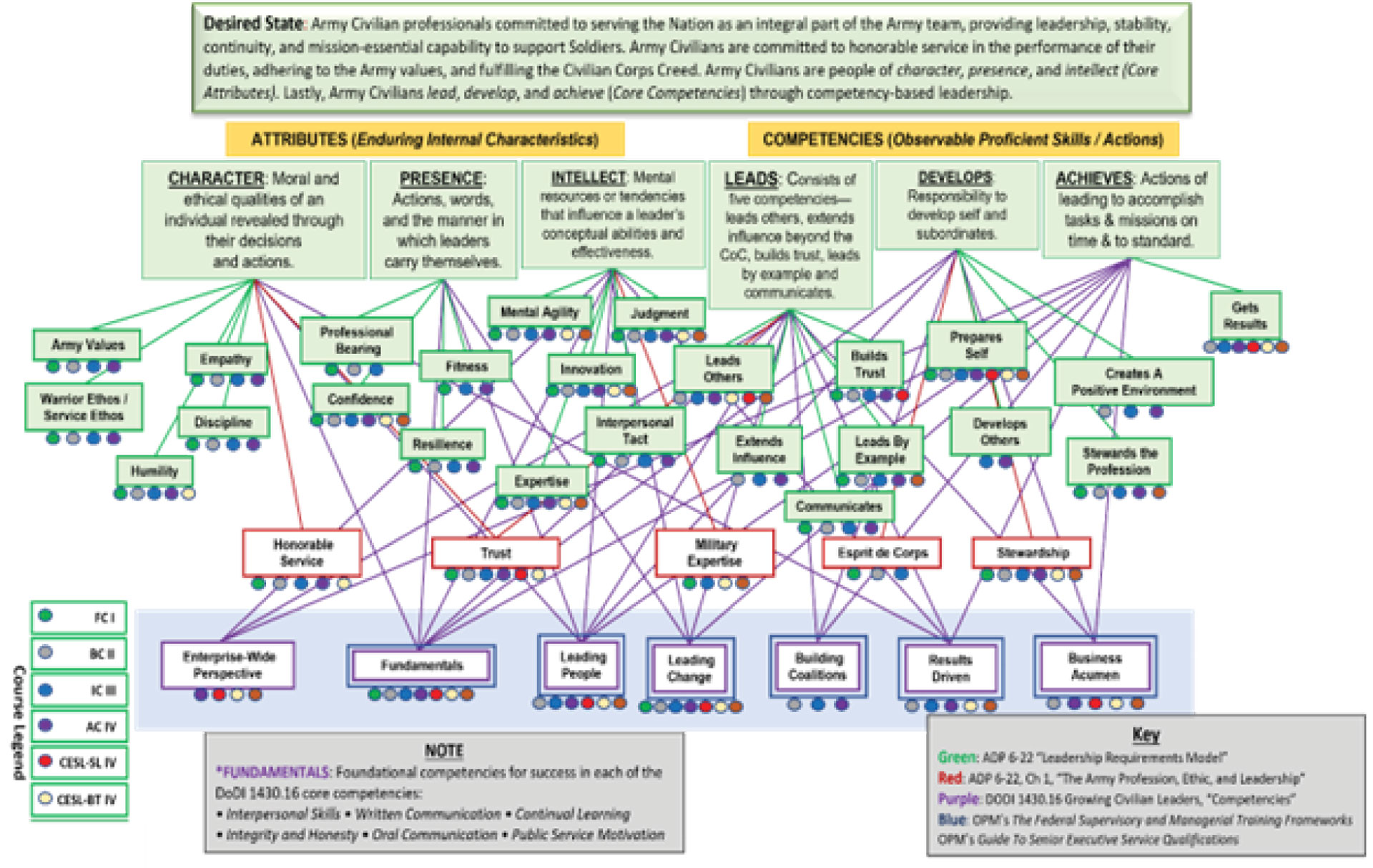

AMSC’s CES courses provide an Army-focused experience grounded in the attributes and competencies needed to succeed as direct, organizational, and enterprise leaders in Army organizations. The specific content of CES courses is derived from authoritative sources. The focus on leadership, commonly identified as the most important skill employees need to develop in programs, is consistent with the top three skills that executives want developed in subordinates: leadership, communication, and collaboration.17 CES curriculum is deliberately constructed to produce outcomes which account for requirements stated in seminal documents. As illustrated in figure 1, the Army Management Staff College mapped the competencies, attributes, skills, and behaviors derived from OPM, DODI 1430.16, ADP-1, and ADP 6-22 to design a curriculum which ensures course outcomes supporting these published requirements.18 CES courses reference the executive core qualifications from OPM at grade appropriate levels in most courses.19

Figure 1. AMSC CLRM Briefing, April 2021 (Figure by AMSC CLRM Working Group, 2020)

Desired outcomes of CES set conditions for mission success, sound decisions, securing of national interests, expertly lead organizations, health climates, and engaged soldiers and civilians.20

Assessment surveys of CES graduates indicate that the return on investment in professional civilian education and development makes a positive and notable difference. Ninety-five percent of participants report CES is relevant to their jobs and 96 percent would recommend to others. AMSC graduates report they’re better prepared to lead a large organization (87 percent) and better prepared to manage a large organization (84 percent) because of the knowledge, skills, attitude, confidence, and commitment derived from CES. Seventy-seven percent of supervisors report improvement an employee job performance attributable to CES attendance.21

CES Courses

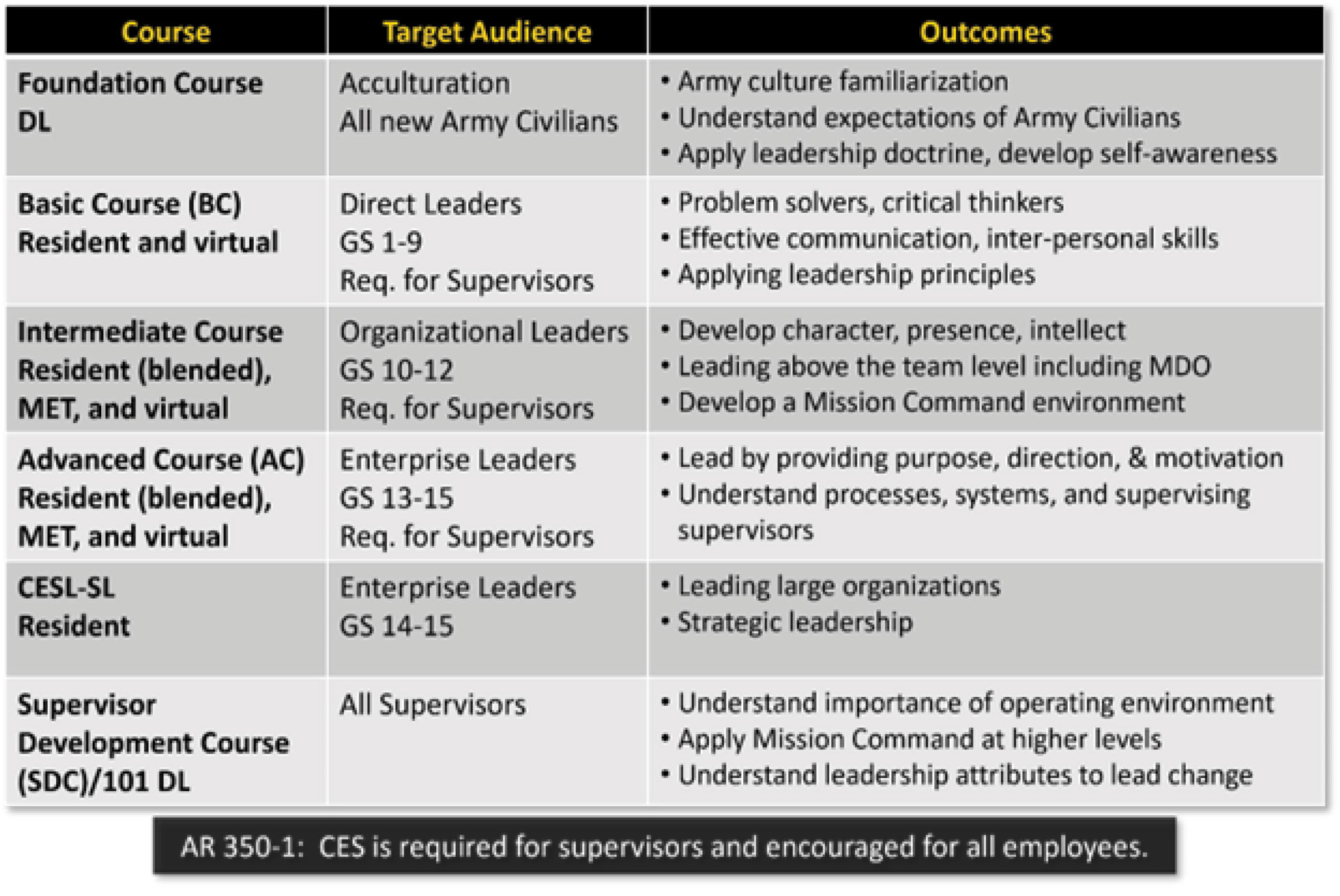

Unlike the uniformed cohorts where virtually all accessions are into lower grades with an aspiration of individual advancement into higher grades, new Army civilians are regularly assessed into all grades, and they can pursue higher grade positions, or they can be fully successful serving in their current grade without up-or-out mandates. This means that CES is not progressive and sequential. Leaders must complete the Foundations course, the Supervisor Development series, and their grade-requisite level of CES as illustrated in table 1.22 It’s not necessary to complete the Basic and Intermediate courses prior to enrolling in the Advanced course. Students who progress through CES in their development find that the educational experience prepares them to successfully lead in any environment throughout their career.

Table 1. Major Army Management Staff College Courses (Table by Frank Wenzel)

CES courses are centrally funded (no cost to the sending organization) and available in multiple modalities to meet the varied needs of individuals and their organizations. These include resident instruction at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Regional Mobile Education Teams at point of need locations; and virtual instruction. The availability of these various modalities mitigates barriers to CES participation.

Employees apply for CES courses through CHRTAS. Eligibility is based on pay grades and priority is given to supervisors followed by aspiring supervisors.

AMSC offers a full suite of courses including the required Foundations course; the recurring Supervisor Development course; and grade-requisite Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced courses. All feature experiential learning for those serving as direct, organizational, or enterprise leaders. Areas of study include leader development and leadership, increased self-awareness, team building, group dynamics, effective communication, an assessment of individual values and ethics, professional advancement, and administrative requirements expected of Army civilians and supervisors.

In addition to these required courses, AMSC also offers courses which are routinely filled to over 100 percent capacity including continuing education for senior leaders, where participants join Army senior leaders discussing current issues facing our Army. Other self-development opportunities include the SECARMY Leader Development Seminar, Action Officer Development course (required for all Army interns), Organizational Leader Development course, Manager Development course, Data Foundations seminar, and Business Transformation seminar. Details for all courses are on the Army University’s home page.

Civilian Development

As they experience their own development, supervisors will realize the unique responsibility and privilege they have in developing others. Hiring actions are the most important tasks a supervisor will undertake. Investing abundant time and attention to this task will yield exponential and recurring benefits to organizations over time. Choosing permanent team members influences success in future missions, turnover rates, the individual’s success, succession planning, and organizational climate more than any other action within a leader’s control. When choosing the team, leaders must avoid the temptation to continually choose members that share the same background, views, and perspectives. By avoiding echo chambers, stakeholders will recognize that a team’s solutions are better developed. Diversity of perspective is a key feature of any successful leadership team.

Once a leader brings a new member into the team, they must remember that loyalty is a two-way street. Be loyal to teammates in all directions along a wiring diagram, always assuming that everyone is trying to what is best for their organization to meet Army requirements. Obviously, leaders will occasionally encounter situations requiring discipline or adverse action, but these are few and far between—and the above referenced CES courses will equip supervisors to effectively mitigate challenging situations.

Effective succession planning develops and sustains a cadre of leaders, maintaining continuity of operations that can respond to future requirements despite normal mission and personnel turbulence. Succession planning is most effective when senior leaders are personally involved and hold themselves accountable for developing subordinate leaders through a rigorous and disciplined process advised by the HR community. This includes recruiting superior personnel; developing their knowledge, skills, and abilities; and preparing them for more challenging positions.23 Succession planning must adhere to merit principles and avoid preselection. This is facilitated by creating a talent pool and evaluating all employees against specific requirements for leader positions by assessing performance in view of competencies, training, education, and developmental assignments.24 Inviting leaders from outside an organization to share their perspectives is an effective way of avoiding groupthink or bias.

The Department of Defense Performance Management and Appraisal Program (DPMAP) is an effective tool for articulating expectations and documenting performance. Coupling this formal system with an informal personal and tailored approach to counseling can set conditions for effective counseling of subordinates. Asking personnel to create individual development plans and including timelines for forecasted attendance at CES courses is an essential part of planning for both parties in counseling sessions. The discipline of setting realistic plans to achieve long-term goals commonly sets individuals on a path toward personal development and achievement.25

The Army Civilian Career Management Agency is working to better support commands by centralizing career management with functional chiefs and career field directors serving as partners to analyze skill sets across the enterprise to shape the workforce. This supports identification of future requirements and opportunities to shape developmental capabilities to meet future Army requirements.

Self-Development

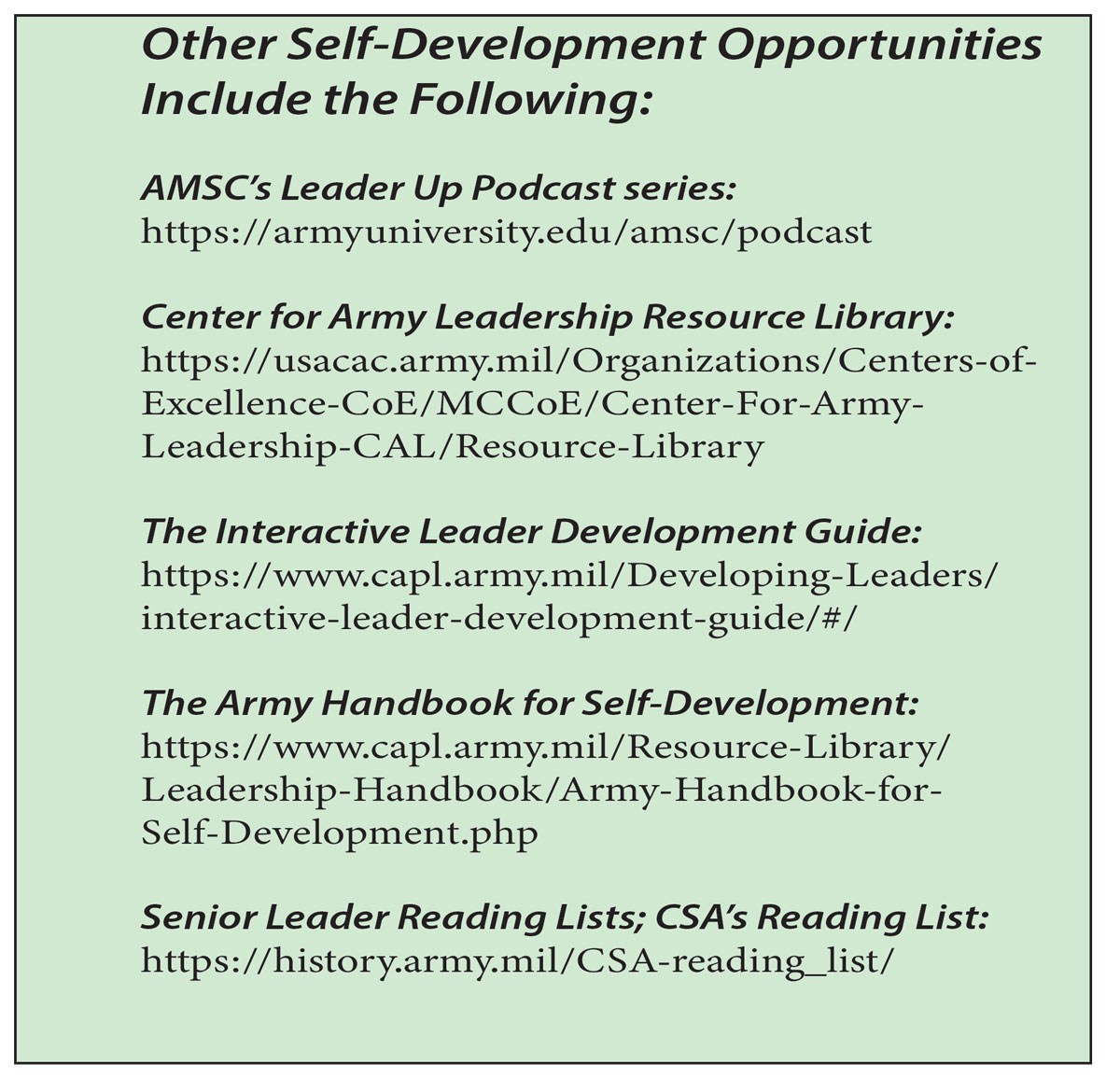

Table 2. Self-Development Opportunities (Table by Frank Wenzel)

Self-development is a constructive bridging of gaps an individual identifies in their pursuit of personal goals. An individual, mentor, peer, or supervisor may each contribute to the identification of areas for self-development. Self-assessment is an essential part of identifying areas for self-development. Institutional and operational domains cannot meet the developmental requirements of all individuals. Self-development fills gaps and reinforces the depth and breadth of what an individual learns in classrooms and their organizational experience. Self-development is most effective when it is planned, competency-based, and goal-oriented. An individual development plan is an excellent tool to use for these purposes. Although inherently a personal responsibility, self-development is more effective when leaders recognize their role in condition-setting and providing feedback.

There are numerous opportunities available for formal self-development. The Army Civilian Career Management Activity (ACCMA) offers fully funded self-development opportunities for Army civilians. These include Army senior fellowships, senior service college, Harvard senior executive fellowships, White House and defense leadership development programs, command and general officer staff officer college, and executive and defense leadership programs. Table 2 lists self-development opportunities available to all Army civilian professionals.

Conclusion

As the executive agent for the Civilian Education System, the Army Management Staff College uniquely provides education for 40,000 students annually, offering an understanding of leader development and leadership, self-awareness, team building, group dynamics, effective communication, assessments of individual values and ethics, professional advancement, and administrative requirements expected of Army civilians.26

Developing Army leaders in all cohorts is the best way to ensure the Army can respond to unknown future contingencies. The Civilian Education System is the Army’s program for developing civilian supervisors.27 In order to provide leadership and continuity, Army civilians need this broad understanding of military, political, and business-related strategies, as well as managerial, leadership, and decision-making skills. The Army’s Civilian Education System equips and enables these professionals to be value-added throughout their careers. Centrally funded, CES serves as the foundation for leader development. Consistent feedback from graduating students and their supervisors confirms that CES is well worth the time investment. Graduated leaders return to their organizations more developed than they left, and their supervisors report that their organization is better off in the near and long term.

Notes

1. Army Management Staff College Semi-Annual Quality Assurance Survey (Army Management Staff College [AMSC], 2023).

2. “2018 Workplace Learning Trends,” LinkedIn, https://learning.linkedin.com/resources/workplace-learning-report-2018; Army Doctrine Publications (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession (U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 2019.

3. Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, 5 U.S.C. § 1101 et seq. (1978); Stephen J. Lofgren (Ed), The Highest Level of Skill and Knowledge: A Brief History of U.S. Army Civilians 1775–2015 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2016).

4. CHRA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016 (Civilian Human Resources Agency [CHRA], 2016); Memorandum from Chief of Staff (COS) to Secretary of the Army (SECARMY), Assistant G-1 for Civilian Personnel, Civilian Human Resources Annual Report (Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2016).

5. CHRA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016.

6. Douglas F. Stitt, Gary M. Brito, and Yvette K. Bourcicot, “The Army People Strategy—Civilian Implementation Plan (APS—CIP),” (Department of Defense [DOD], 2022), https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2022/10/31/fa993f31/signedarmypeoplestrategy-civilianimplementationplanfy23-25-508-wo-annexes.pdf.; Memorandum from COS to SECARMY, “The Army Civilian Corps.”; Lofgren, The Highest Level of Skill and Knowledge; 10 U.S.C. § 3013 (2011); “The Army’s Vision and Strategy,” Army.mil, https://www.army.mil/about/.

7. Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 1430.16, Growing Civilian Leaders (Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, 23 August 2022).

8. Army Regulations (AR) 690-950, Career Program Management (U.S. GPO, 2016).

9. AR 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development (U.S. GPO, 2017); David T. Culkin, “The Civilian Education System and Total Army Readiness,” Army.mil, 18 May 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/256818/the_civilian_education_system_and_total_army_readiness.

10. Terry McDonough and Cheryl Oldham, “Why Companies Should Pay for Employees to Further Their Education,” Harvard Business Review, 19 October 2020, https://hbr.org/sponsored/2020/10/why-companies-should-pay-for-employees-to-further-their-education; “10 Talent Development Statistics You Need to Know in 2024,” InStride, 17 January 2024, https://www.instride.com/insights/talent-development-statistics/.

11. Colin Burton, “25 Reasons Why Training Your Employees is Important,” Thinkific, 6 February 2025, https://www.thinkific.com/blog/why-training-is-important/.

12. Civilian Human Resource Training Application System (CHRTAS), CES Supervisor Development Course Report (AMSC, 2024).

13. Vicki A. Brown, “Human Resources and Employee Engagement: A Critical Alliance,” Presentation, Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service, Washington, DC, 2016.

14. “2018 Workplace Learning Report,” LinkedIn, https://learning.linkedin.com/resources/workplace-learning-report-2018

15. AR 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development.

16. John E. Hall, “Developing Leaders in the Army Civilian Corps,” Army.mil, 4 January 2016, https://www.army.mil/article/159956/Developing_leaders_in_the_Army_Civilian_Corps/.

17. “2018 Workplace Learning Report.”

18. U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM), “Executive Core Qualifications,” accessed 23 April 2024, https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/senior-executive-service/executive-core-qualifications/; ADP 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession (U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019); ADP 1 The Army, (U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019); DODI 1430.16, “Growing Civilian Leaders”; Ibid.; ADP 1 The Army; ADP 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession.

19. OPM, “Executive Core Qualifications.”

20. ADP 6-22 Army Leadership and the Profession.

21. Army Management Staff College Semi-Annual Quality Assurance Survey (AMSC, 2023).

22. AR 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development.

23. Hall, “Developing Leaders in the Army Civilian Corps.”

24. AR 690-950, Career Program Management (U.S. GPO, 16 November 2016).

25. AR 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development.

26. Hall, “Developing Leaders in the Army Civilian Corps.”

27. AR 350-1, Army Training and Leader Development.

Authors

T. Gregg Thompson was appointed to the Senior Executive Service in February 2019 and assumed his current position as the deputy to the Commanding General, U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, in June 2022. He has a BA in economics, an MEd in adult education, and an MA in strategic studies.

Frank Wenzel (Ret.) was director of the Army Management Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He retired from service as a colonel, having joined the U.S. Army as a private in 1987 and commissioned through the United States Army Officer Candidate School in 1988. He has a Master of Military Art and Science degree and a Master of Science degree from Kansas State University; a Bachelor of Arts degree from California State University, Fullerton; and is a resident graduate of the Advanced Operation Art and Studies War College Fellowship and the United States Army Command and General Staff Officer College.