Russian River Crossing Failure During

the Battle of the Siverskyi Donets

By MAJ KYLE KINDY

Article published on: May 8, 2025 in the Spring Issue of the infantry journal

Read Time: < 13 mins

On 8 May 2022, the Russian army attempted to cross the Siverskyi Donets River in the Donetsk region of eastern

Ukraine. The crossing operation failed, and an entire Russian battalion tactical group (BTG) was lost. Russia's

failed river crossing is an example of why the principles of the offense and the training and employment of

combined arms remain paramount to successful obstacle negotiation.

Background

Russia began the special military operation in Ukraine in late February 2022. When an initial drive towards Kiev

from Belarus was thwarted, the Russian operational planners adopted a more conservative approach by massing

combat power and shortening logistical lines of communication along select axis of advance on Ukraine’s eastern

border. By May 2022, Russian forces advanced through the Luhansk region to the cities of Severodonetsk and

Lysychansk. Meeting significant resistance in Severodonetsk, the Russians attempted an encirclement, hoping to

either dislodge the Ukrainians or isolate them in a siege.1 By dislodging the Ukrainians, Severodonetsk would be given up, but the

Ukrainian forces would be preserved. A siege would have trapped the Ukrainians forces in the city to be dealt

with later while the offensive continued westward uninterrupted.

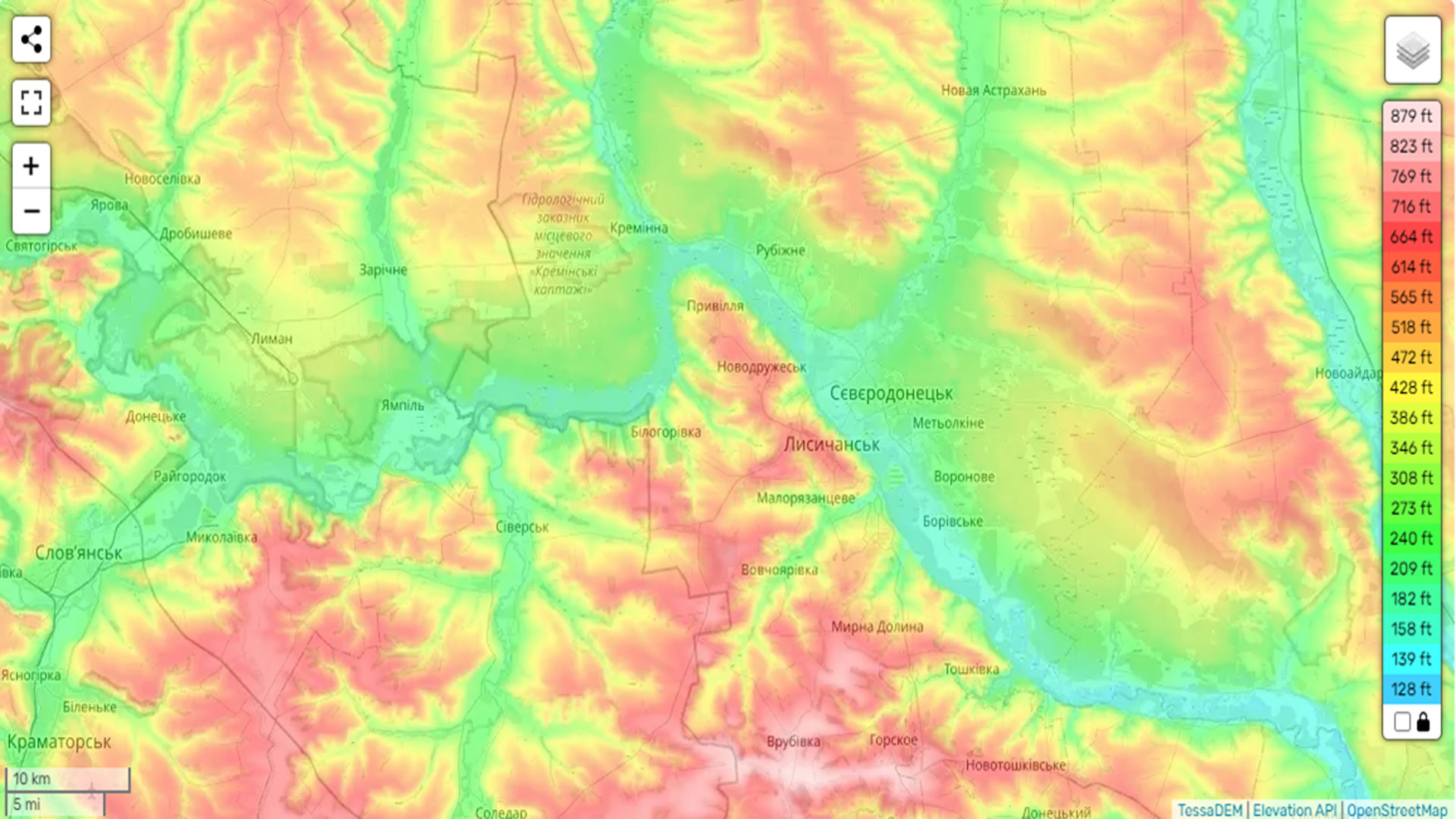

Terrain

Severodonetsk and Lysychansk are key cities in the Donetsk region. This region of Ukraine is a heavy industrial

area and a world leader in metallurgical production, and the city of Severodonetsk is home to the Azot chemical

plant.2 The industrial nature of

these cites provides hardened structures that increase survivability against Russian air and artillery fires. A

major highway runs through Severodonetsk which connects Luhansk, Kramatorsk, Donetsk, and Kharkiv.3 This makes control of Severodonetsk

critical for controlling access to the Donetsk region. Ukrainian forces were holding these cites to prevent

Russian forces from gaining access to an avenue of approach into the larger Donetsk region.

The vegetation near Severodonetsk is mostly small forests of pine and oak covering steppe with hills that reach

to approximately 650 feet in height. At the time of the attempted crossing, Ukrainian defenders on the southwest

side of the Donets River held an advantage in terms of elevation over the Russian advance across the Donets

River.

The Siverskyi Donets River is the largest river in the region; it averages 8-feet deep and ranges from 115-230

feet wide, a significant natural barrier. In 2022, the Donets River was a limit of advance for the Russian

forces operating in northeast Ukraine.

Figure 2 - Photo of the Crossing Site and Destroyed Pontoon Bridges and Vehicles (Photos

courtesy of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine)

Figure 2 - Photo of the Crossing Site and Destroyed Pontoon Bridges and Vehicles (Photos

courtesy of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine)

By this point in the conflict, most span bridges across the Donets River

were destroyed. Surviving bridges typically connect directly to population centers, increasing the risk to

security and elements crossing the exposed bridge while defenders are obscured and protected in buildings. The

Russian military decided to conduct a river or wet gap crossing, which is an extremely dangerous offensive

operation where military units cross rivers by moving through them (fording) in amphibious vehicles or building

bridges to cross the river. Most Russian vehicles including their main battle tanks are capable of fording

rivers, and the decision to conduct a wet gap crossing gave them the initiative and ability to select favorable

terrain, river width, and depth. The Ukrainians were aware of this, and they were also familiar with Russian

doctrine and crossing-site criteria (ideally located at bends or “U’s”). Understanding that the Russian

commanders were under pressure to report tactical gains along this front, they made a deliberate effort to

identify potential wet gap crossing locations in the vicinity of Severodonetsk and Lysychansk.

Preparations

Figure 3 - Close-up Photo of the Destroyed Vehicles

A first-hand account made in Newsweek by a Ukrainian engineer and explosive ordnance disposal officer named

Максим (Maxim) claims, "he was among the experts sent to do engineering reconnaissance on May 7 and 8 on the

Siverskyi Donets River ahead of a possible crossing by Russian troops. Russian forces had gathered on the other

side of the river from the settlement of Bilohorivka, according to the tweet from Maxim. So, he headed to the

area surrounding the settlement and the nearby village of Hryhorivka to assess where Russian troops could

possibly attempt to mount a pontoon bridge and cross the river. Maxim said he assessed that Russian troops would

have needed at least 8 parts to complete a floating bridge capable of crossing the over 260 feet wide river, and

that it would take them at least two hours of work to do so."4

On 8 May, the Russian 74th Motorized Rifle Brigade of the 41st Combined Arms Army began the wet gap crossing

operation preparations. The site selected by the Russians, identified in Figure 1 by a red box, was a relatively

low spot compared to Ukrainian-held territory on the opposite bank. Vegetation in the region was in full foliage

in May, but the overhead cover at the crossing was intermittent and did not mask much of the crossing area or

far side assembly area from aerial observation. The firsthand account by Maxim indicates there was fog during

the initial build of the pontoon bridge.5

Weather data recorded no rain in the week preceding the crossing and partly cloudy conditions on the days

of the operations with average temperatures.6

Ukrainian artillerymen of the 17th Tank Brigade, 80th Separate Assault Brigade, and the Ukrainian Air Force were

observing the

Russian forces but avoided occupying the riverbanks to protect their forces from direct fire and foster the

Russian sense of security at the crossing site.

Execution

On 8 May, the Russian army started forest fires and obscuration operations to conceal the crossing and began

moving forces over the pontoon bridge. The Ukrainians did not engage immediately, according to Maxim.

“‘Artillery was ready,’ he said. ‘In 20 minutes after [our] recon unit confirmed Russian bridge being mounted,

heavy artillery

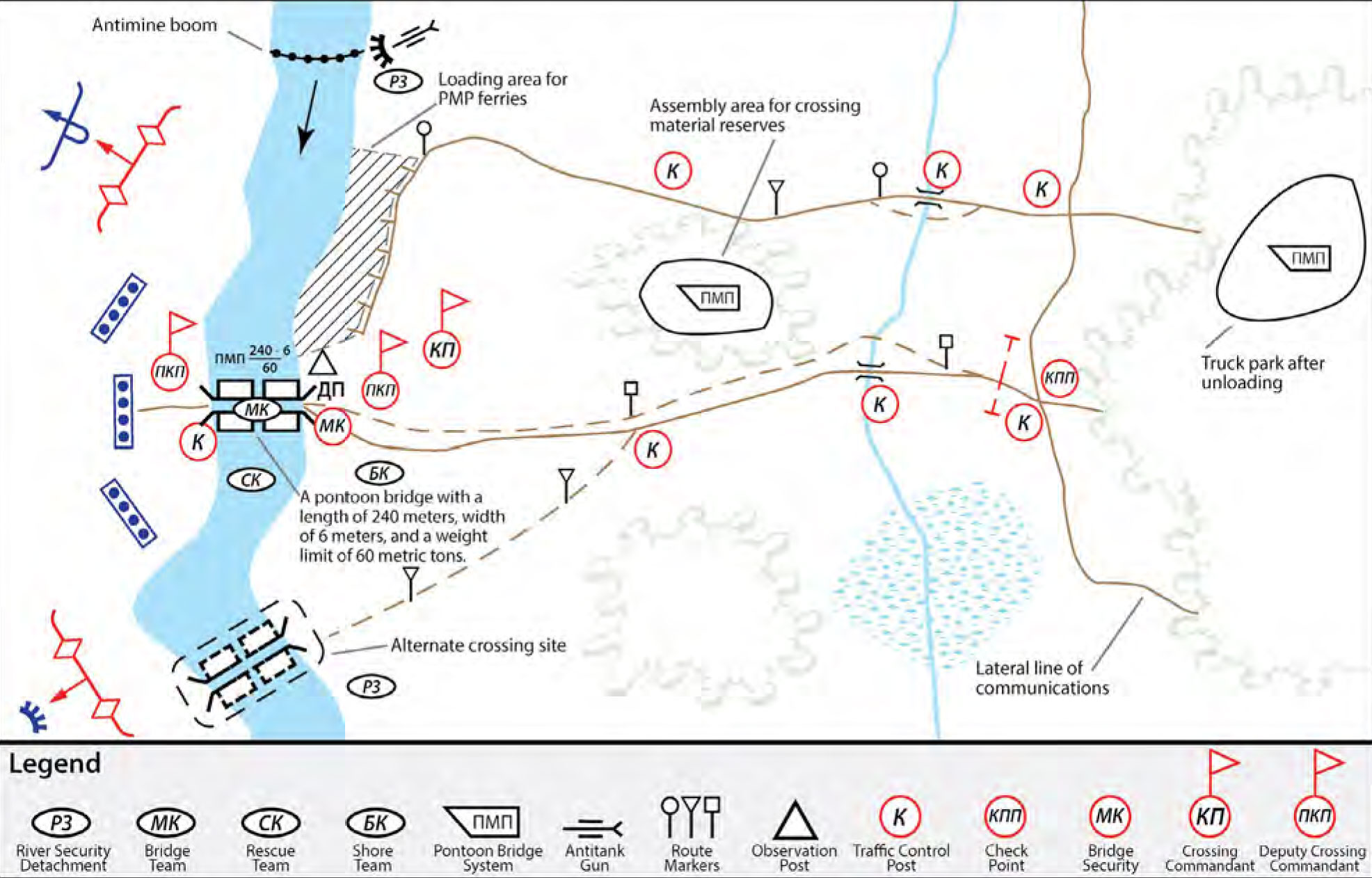

Figure 4 — Deliberate Bridge Crossing11

engaged against Russian forces, and then aviation chipped in as well… After one day of combat… the bridge was

down,’ Maxim added. ‘Some Russian forces were stuck on Ukrainian side of the river with no way back. They tried

to run away on broken bridge. Then they tried to arrange a new bridge. Aviation started heavy bombing of the

area and it destroyed all the remains of Russians there and other bridge they tried to make.’”7 Estimates of Russian losses during

the crossing operation vary. Between 50-70 T-72Bs, T-80s, BMPs, and engineering assets were destroyed; loss of

life figures ranged from 300 to 1,000 soldiers killed in action from 8-10 May. Ukrainian losses were assumed to

be negligible; none were reported.

Assessment

This defeat was another highlight in a surprisingly underwhelming demonstration of operational and tactical

prowess by the former Cold War superpower. Russia is considered a peer of the United States in the great power

competition and one that has not been encumbered by decades of counterinsurgency warfare eroding its mindset for

high-intensity large-scale combat operations. Why did the events unfold as they did in May 2022? How should this

terrain be negotiated in military operations? What aspects of offensive operations did the Russians fail to

achieve for this operation?

Wet gap crossings have always been a major challenge for operational planners, particularly in Europe. The

Russian military has a doctrine or procedure for negotiating natural obstacles of this nature. In his article

"Russian Deliberate River Crossings: Choreographing a Water Ballet," Dr. Lester W. Grau explains that the

Russians categorize crossings as hasty or deliberate.8

Hasty crossings are executed from the march formation in an uncontested or lightly defended crossing site. This

form of crossing takes advantage of the amphibious capabilities of Russian infantry fighting vehicles such as

the BMP and BTR family, with these vehicles fording the river to establish security on the far side bank. The

use of air assault forces to secure the far side is also recommended with a hasty crossing, allowing the lead

battalion to maintain its momentum during the crossing and continue movement away from the crossing site. Water

less than 5 meters deep can also be forded by Russian tanks if the bottom and riverbank compositions are viable.

As combat forces push further from the river crossing site, they create a pocket of security for higher echelon

enablers to cross in. Follow-on forces in the brigade can then cross at a slower pace via ferry or bridging in

relative security.

A deliberate crossing is conducted when resistance is expected, and the enemy has time to prepare a defense. In a

deliberate crossing, Russian forces deploy into attack formation from the march, and artillery assets are

brought forward to provide direct and indirect fire support. Once the enemy forces on the opposite side of the

river have been depleted, the lead battalion will ford the river, or a follow-on battalion will maintain its

movement forward by passing through the attacking lead battalion to ford the river and establish a beachhead on

the far side riverbank. (See Figure 4).

In The Russian Way of War: Force Structure, Tactics, and Modernization of the Russian Ground Forces, Dr.

Grau and

Charles Bartles detail some actions Russian doctrine recommends the attacking force should take prior to and

during wet gap operations, some of which have already been discussed. Relevant to the crossing of May 2022,

Russian doctrine recommends the following:

- Cross on a wide front at a quick tempo;

- Air defense assets should cover the crossing and preparation areas;

- A deliberate attack involves far more artillery and aviation preparation; and

- Smoke, air defense, and counterbattery efforts are particularly critical.9

Dr. Grau also includes coordination planning factors in his later work: “Coordinating a deliberate crossing

requires:

- Choreography of artillery preparation and supporting fire.

- Aviation strikes.

- Air assaults (to seize the far bank).

- An attack, from the march, that puts the first-echelon infantry fighting vehicles and/or personnel carriers

online

shortly before reaching the near bank so that they can cross simultaneously.

- A separate tank crossing conducted by snorkeling or crossing on a pontoon bridge or on ferries.

- A camouflage and deception effort.

- A bridging effort.

- The development and continuation of the advance on the far shore."10

By recalling the firsthand account of Maxim and examining the imagery of the crossing site taken immediately

following the battle, some assumptions and deductions about the details of the battle are evident. The Russians

selected a

Figure 5 - Aerial View of the Pontoon Bridge During the Battle(Photo courtesy of Luhansk

Regional Military Association/Blacksky)

textbook location for their river crossing (bend in the river with gentle sloping terrain on both sides) and from

the reports received by the Ukrainian defenders followed their doctrine of staging and equipment preparations

prior to crossing. Ironically, this adherence to procedure also allowed the Ukrainian engineers to confirm the

intended crossing site and prepare a defense. It can also be assumed both Russian and Ukrainian reconnaissance

elements accurately assessed the composition of the river bottom and banks as unsuitable for tank fording, thus

the immediate employment of the pontoon bridges versus fording. Russian commanders then departed from their

doctrine; the required coordination that was previously mentioned begins a list of things the Russians did not

do.

Deception and camouflage steps were not done properly. There was no mention of activity in multiple sites along

the river to force the Ukrainians to divide their assets or cause uncertainty of exact Russian crossing

intentions. Artillery was not moved forward to provide indirect suppression of Ukrainian artillery, direct fires

on the opposite bank and ridge line, or to counter Ukrainian fires during the crossing. Aviation strikes were

not carried out to reduce defensive capability immediately before the crossing was conducted. The use of

obscuration fires seems to have taken place and is likely the cause of the forest fires and large areas of

charred ground seen in pictures taken after the battle. But, with only one bridging site at a textbook location,

preplanned fires and unguided munitions remain effective. The Russian lead elements maintained their momentum

when the order to cross the 260-foot bridge was given but not on a broad front, and they halted in the low land

on the opposite side of the river, presumably to consolidate and build combat power before moving to the high

ground.

The Ukrainians showed tactical patience and allowed 20 minutes for vehicles to build up on their side of the

river before opening fire with artillery and calling in aviation airstrikes. No counterbattery fire from the

Russians was reported, which exposed another failure: Air defense units had not moved into a position to defend

the bridge or the units on the far side of the river after crossing. With both exposed to massed artillery and

air strikes, it was only a matter of time before the bridge was destroyed and forces were isolated on the far

side. No mention was made of any close air support or artillery support given to the forces stranded on the

Ukrainian side of the river. A photo taken during the battle shows an intact pontoon bridge, and the depth of

the Russian penetration can be identified by the smoke of burning vehicle hulls all the way up to the ridgelines

(see Figure 5).

Crossing a natural barrier like a river is an inherently risky military operation. In this case the Ukrainians

made excellent use of their elevated positions to conceal their forces from direct fires and extend the range of

their indirect fires. The Ukrainians’ crossing site analysis allowed them to concentrate their defenses at

specific points. The Russians contributed more to their own defeat than the enemy did in many ways. The lack of

combined arms and use of air defense enablers to protect the vulnerable bridge resulted in the unnecessary

exposure of forces. Allowing the Ukrainian defenders to concentrate artillery with no threat of counterfires and

allowing the Ukrainian aviation to operate uncon¬tested doomed the operation to failure, and a battalion of men

and equipment was lost. It is possible that this operation would have succeeded if the Russians had suppressed

Ukrainian artillery, protected their forces with anti-air defense systems, and allocated aviation support.

In relation to the principles of the offense in American doctrine, the Russians failed to achieve surprise and

maintain their tempo on the far side of the crossing site and made no attempt to concentrate effects to set

conditions for the operation. They were overly audacious to conduct an unsupported wet gap crossing against a

determined, capable, and prepared Ukrainian military. Consequently, the risk accepted by the Russian commanders

on the ground was negligent.

Conclusion

The materials and construction methods to traverse rivers have certainly improved over time, but the constrictive

nature of the crossing has remained constant. Doctrine and techniques mitigate the risk, but it is dependent on

commanders to ensure the tools at their disposal are properly used. The enemy also has a vote, and near-peer

adversaries possess tools and techniques to combat wet gap crossing forces. It is unclear if the Russian forces

were attempting to take advantage of an element of surprise or if they were experiencing a lack of resources.

Perhaps this was a case of higher-level pressure demanding progress combined with a rushed plan executed at the

cost of human lives. Or, the Russian forces may have just been overconfident in their abilities. What is clear,

though, is that the Ukrainian use of geography and shaping forced the Russian military to unsuccessfully conduct

one of the most hazardous operations any military force can attempt. The Ukrainians' analysis of the river and

understanding of their opponents' capabilities allowed them to identify crossing sites and build a defensive

plan that favored their strengths and exploited the Russians at a vulnerable moment in the crossing, ultimately

leading to the loss of a BTG.

As U.S. leaders and warfighters make the shift towards large-scale combat operations, it is vital to practice the

doctrine and discipline that synchronize the incredible capabilities we have as a joint force. Additionally, we

have a unique opportunity to observe our competitors in action to learn from their mistakes and vulnerabilities.

The Russian failure on the Donets River is a modern-day testament to

the persistent hazard of wet gap crossings and the validity of doctrine founded in lessons learned.

Endnotes:

1. Sophie Williams and Olga Pona, "Bloody River Battle was Third in

Three Days Ukraine Official," BBC News, 13 May 2022,

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61399440

2. Encyclopedia Britannica, "Donbas,"

https://www.britannica.com/place/Donbas; Roman Goncharenko, "The Strategic Value of Sievierodonetsk,"

Deutsche Welle, 6 September 2022,

https://amp.dw.com/en/why-ukraines-sievierodonetsk-is-so-important/a-62001664

3. Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation,

Donetsk People's Republic, http://www.council.gov.ru/en/structure/regions/X2/

4. Guilia Carbonaro, "Ukrainian Soldier Reveals How He Secretly Blew

Up Russian Bridge," Newsweek, 12 May 2022,

https://www.newsweek.com/ukrainian-soldier-reveals-how-he-secretly-blew-russian-bridge-1706083

5. Ibid.

6. Time and Date, Past Weather in Donetsk, Ukraine, May 2022, https://www.timeanddate.com/weather/ukraine/donetsk/historic?month=5&year=2022

7. Charlie Parker, "Russian Battalion Wiped Out Trying to Cross River of Death," The Times, 12 May 2022,

https://www.thetimes.com/world/russia-ukraine-war/article/russian-battalion-devastated-as-it-crosses

8. Dr. Lester W. Grau, "Russian Deliberate River Crossings: Choreographing a Water Ballet," Engineer, September-December 2019.

9. Dr. Lester W. Grau and Charles Bartles, The Russian Way of War: Force Structure, Tactics, and Modernization of the Russian Ground Forces

(Fort Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office, 2016),

https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/Hot%20Spots/Documents/Russia/2017-07-The-Russian-Way-of-War-Grau-Bartles.pdf

10. Grau, "Russian Deliberate River Crossings."

11. Ibid.

Author

MAJ Kyle D. Kindy currently serves as a sourcing officer, G3/5/7, National Guard Bureau, in Arlington, VA.

His previous assignments include serving as a maneuver plans officer, G35, 36th Infantry Division (Forward)

and commander of A Company and Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 142nd Infantry

Regiment, Texas Army National Guard. MAJ Kindy began his military career as an enlisted Marine, serving with

1st Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He later served as an

Army Reserve drill sergeant and commissioned in the Army National Guard through the Accelerated Officer

Candidate School at the Alabama Military Academy in 2009. He is a graduate of the Urban Warfare Planner

Course, Ranger Course, Marine Scout/ Sniper School, Marine Basic Reconnaissance Course, and Marine Anti-Tank

Assault man Course. MAJ Kindy earned a bachelor's degree in general studies from West Texas A&M University,

and he is currently pursuing master's degrees in emergency and disaster management at Georgetown University

and military operations at Liberty University in Lynchburg, VA.